Our narrator is back and quick to inform us that Miss Minturn has secluded herself in her stateroom in order to update her diary—as she has not been given the opportunity previously. In a slip of chronology this is imperative, in order to enlighten readers to events prior to departure, of which they have already read. However, throughout the chapter, the narrator remains primarily in touch with Miss Minturn’s point of view, and she is the key character in revealing the narrative, through speech, thoughts and what she hears and sees.

Social class and what it means in this new society of the Americas is the theme throughout the chapter. Near the end of the chapter ‘the 400’ are mentioned, which to modern readers may be unfamiliar. The social matriarch for some time in New York was a Mrs. Caroline Schermerhorn Astor. The term was coined by a loyal courtier, Ward McAllister, man-about-town as a social index: “Four Hundred”—a reference to the people who mattered in society, and the number of guests who could fit into Mrs. Astor’s ballroom. Caroline Schermerhorn came from a shipping family and married a grandson of fur trader John Jacob Astor, the richest man in America at the time (Broyles). This doyen of New York high society presided over what was previously known as the knickerbocracy. This term was derived from an 1908 novel by Washington Irving. Knickerbocker being the name of his facetious non-de-plume in a book that parodied the early Dutch settlers of New York (Morrow). For the social set that surrounded Mrs. Astor was not only about old money, but also critically old blood-lines.

Cornelius ‘Commodore’ Vanderbilt, shipping and railroad industry magnate, and his family were excluded. Alva Vanderbilt, the wife of William Vanderbilt, the Commodore’s grandson, decided that they should be part of ‘the 400’ and sought to bring the Vanderbilt family the social status they deserved (Morrow).

Alva had a mansion built on Fifth Avenue, that surpassed the size of her neighbors’, then set about planning a costume ball for the opening. For the first time, the press were invited in to view and photograph the venue where the ball would take place. The third floor gymnasium was filled with palm trees and bougainvillea to resemble a jungle. Women of society spent months and considerable expense in having their costumes made. In short, having an invitation was the hottest ticket in town. Reportedly, Mrs. Astor’s daughter, Carrie had not received an invitation, although all her friends had, so she appealed to her mother to intervene. Mrs. Astor asked Alva Vanderbilt why her daughter had not received an invitation. To which Alva replied, that as Carrie had not visited the house, it would have been improper to have sent her an invitation. This then required Mrs. Astor to have her card left at the Vanderbilt house. This was the acknowledgement that Alva had been waiting for as it meant they had been recognized as part of the social fabric of New York. Carrie Astor and the rest of the Astor family received invitations the next day (Morrow).

The ball took place on 26th March, 1883. New York had never seen a social event of such size and opulence. Police held the crowds back as the more than eight hundred invitees dressed in the most wonderful and bizarre costumes that anyone had ever seen arrived. Taking inspiration from her nickname ‘Puss’, Miss Kate Strong’s costume consisted of a taxidermied cat on her head, and cat tails dangling from her skirts. The ‘Duchess of Burgundy’ was Miss Edith Fish’s choice with rubies, sapphires and emeralds adorning the front of her dress. Lila, Alva’s cousin went as a hornet with a spiked stinger adorning her head, encrusted with diamonds and other precious gems, while Alva’s own costume lit up due to batteries hidden in the dress. At eleven thirty the first of a series of quadrilles began, the most notable; the Dresden Quadrille where dancers all dressed in white took on the appearance of porcelain figures come to life (Broyles). At two a.m., guests selected their dinner, prepared by chefs from Delmonico’s and other Vanderbilt homes, and served by a corps of servants dressed in costume (NY Tribune) . The dancing continued until dawn. The estimated cost of the event was US$250,000 at the time, the equivalent of six million dollars today (Broyles).

A journalist with the New York Sun took issue with the flagrant show of opulence on several levels:

‘Old, sober- minded men ask themselves whether it is advisable to make such a display of wealth and luxurious living when working classes are in a state of serious fermentation all over the world….The festivity represents nothing but the accumulation of immense masses of money by the few out of the labor of the many. … it was American only in its extravagance. In all the rest it was thoroughly foreign-in costumes, characters, fabrics, laces, dances, music, refreshments and everything else.’

New York Sun 29/03/1883

Louise Minturn has the education, the commonplace nous she is proud of, and some affinity with other members of the working class, but she also has a known blood-line attached to her name, and in this way she crosses the line between social classes. To some extent, everyday formality is relaxed on the steamer Colon; however, the perceived obstacle social caste places in the path of true love cannot be expunged from her thoughts.

CHAPTER 11

AN EXILE FROM THE FOUR HUNDRED

For two days, on the plea of seasickness, a vague bashfulness keeps this young lady in retirement, in spite of kind messages from the captain, brought by the stewardess, suggesting it will be well for her to get her “sea legs” in working condition, and that his table looks lonely at dinnertime: for the skipper, being an admirer of lovely women, has given her this post of honor, somewhat to the young lady’s astonishment. Not being seasick—for the weather is by no means tempestuous—she has devoted herself to writing up her diary, which has fallen behindhand in the two or three days previous to her departure from New York.

On the morning of the third clay, the stewardess, opening Louise’s stateroom door, with that young lady’s coffee in her hands, says, in her goodhearted darky way: “Miss Minturn, Cap’en’s compliments, an’ hopes to see yo’ at breakfus’.”

Then getting no answer to this but a piquant yawn, for the young lady is sleepy, she runs on in her patois:

“’Deed it ’ud be a pow’ful shame if yo’ don’ go, honey. De vessel ain’t rockin’ mo’ dan a baby’s cradle. Dis am reg’lar Bahama wedder.”

“Can I wear a light dress?” the girl asks suddenly and rather anxiously, reflecting, in a sleepy way, that her new summer gowns are her strongest points in wardrobe: and desirous, like other Eves, to make a good appearance on her first entry into the dining salon.

“Laws! Yo’ could wear angel’s wings, yo’ could, today, an’ be comfo’table!” returns the stewardess.

“Oh!” cries Louise, laughing. “I have no wish for a celestial toilette. Nun’s veiling will make me near enough to the angels at present.”

Soon after, stepping upon the deck, a vision of summer loveliness, she feels sorry that she has confined herself to her stateroom so long. The vessel is ploughing her way through a sea that is strangely blue, and quiet as the waters of an inland lake, save for its long ocean swell. The sky above her is also azure, and the glorious sun makes the bracing sea breezes a little languid, as they toss the girl’s hair about, and give undulation to skirts and draperies that outline as pretty a figure as ever stood upon a ship’s deck. She draws in the salt air, which is just strong enough to give buoyancy to her step and roses to her cheeks, and is happy that she has left New York with its March winds behind her, and sailed into a sunny sea.

Everything is tropical.

She looks about, an indefinite bashfulness in her radiant eyes, as if she hoped, yet almost feared, to see someone, and notices the passengers are nearly all in the toilettes of midsummer: the gentlemen mostly sporting white linen suits or flannels: the ladies in light yachting costumes, with dainty sailor hats, or other delicate dresses suggestive of the tropics.

The gong is sounding for breakfast. Miss Louise, with a little disappointed pout upon her lips, for some how she has not seen what she has been looking for, is about to go a little diffidently into the dining salon. But at the companionway a cheery voice greets her. The captain is at her side, saying pleasantly—for this old sea dog has a quick eye for pretty girls—“I hope you have got a saltwater appetite, Miss Minturn. Delighted to see you on deck. I was afraid you might make the voyage ‘between blankets.’”

“In such beautiful weather that would have been horrible,” replies the young lady.

“If you had not come out today, I was going to send our sawbones to see what was the matter with you,” returns the captain.

“Oh!” says the young lady, withdrawing her hand from his vigorous and hearty grasp, for the skipper has been giving its taper fingers a cordial squeeze, “I never take doctor’s prescriptions.”

“Neither do I!” laughs the seaman: “so come down and take some of our cook’s.”

A moment after, they are at the breakfast table, the waiter placing a chair for Miss Louise at the left hand of the captain, as the latter introduces his pretty charge to the people immediately about him. During these presentations, the young lady discovers that the chair at the captain’s right is occupied by the wife of a French engineer connected with the Panama Canal Company. She is going to join her husband on the Isthmus, and is very petite, rather timid in her manner, and delighted when she learns that her new acquaintance speaks French.

Immediately beyond this lady is an American, Colonel Clengham Cleggett by name. He is in some way connected with the American Commission for the Panama Canal, and is at present enthusiastically praising the French management of that gigantic enterprise, probably because he receives therefrom a handsome salary. A little farther down the table is a very pretty American girl going by way of the Isthmus to meet her fiancé, who is an orange farmer in Los Angeles, California, where she is to be married to him. Her name at present is Miss Madeline Stockwell.

These things come to Miss Minturn in a dreamy manner. With change of latitude, the atmosphere seems to have changed also. Though the flag of the United States floats over her, she is apparently no longer in America.

Everything about her is so foreign!

The conversation at the next table, coming from several young Central Americans returning to their coffee plantations, is Spanish. The balance is almost entirely French. There is but one subject of remark—the Panama Canal. For nearly all of the passengers are connected with it, and get their bread and butter out of it, being employees of the Canal Company, of the various contracting firms engaged in constructing it, returning from leave of absence to their duties on the Isthmus.

The only exceptions to this, besides those mentioned, are a couple of English Chilians bound for Valparaiso, and a representative of Grace & Company, going to Lima. Therefore the name of le grand Franc̗ais, Ferdinand de Lesseps, and his colossal enterprise, is on everybody’s lips.

But even as these things come to her, the young lady’s pretty hazel eyes are looking diffidently, yet anxiously, about her. She is wondering where Mr. Larchmont sits in the dining salon. She rather hopes it is far from her; next suddenly wishes the reverse. Even as this thought is in her mind, a great blush comes over her beautiful face, she turns her head away for a moment, confused, for Harry Larchmont, coming down in summer flannels, takes the vacant seat next to her. Looking at the beauty beside him, he gives a start of surprised pleasure, and ejaculates: “I was afraid you were overboard!”

The captain says: “Harry” (for this young man’s easy going way has made him familiar with nearly everybody on shipboard), “let me introduce you to Miss Minturn. She is the derelict of the ship. You should know her. She is one of your set in New York.”

To this peculiar information, Mr. Larchmont says with the instinctive good breeding of a man of the world: “Yes, I know Miss Minturn very well, I am happy to say.”

“Of course you do!” laughs the captain. “She danced at the Patriarchs’ ball with you the other evening.”

“No, you are referring to my first cousin, Miss Fanny Minturn,” ejaculates Miss Louise, suddenly finding her tongue, and not wishing to sail under false colors.

“Miss Fanny Minturn is your cousin?” says Mr. Larchmont, a look of surprise passing over his face, for which the young lady does not bless him, for into her quick mind has flown this thought: “Why should this gentleman be astonished at Miss Minturn of Fifth Avenue being the cousin of Miss Minturn the stenographer?” As she thinks this, chagrin makes her its prey. She imagines the captain’s politeness and seat at his table came because he had supposed her one of the elect of New York. Fortunately for her peace of mind, she soon discovers that she does this jovial, goodhearted sea dog injustice, as he don’t care anything for Fifth Avenue. All he cares for is pretty girls: and Miss Minturn’s face and figure having pleased him, he has given her a seat at his table, and will favor her with personal attentions during the voyage, that he would hardly give to an ugly countess.

As the look of annoyance leaves her face, the conversation becomes more general, though ever and anon, during its commonplaces, the pretty young lady seated at Harry Larchmont’s side, catches his eyes upon her, and she interprets their glances to say: “What the dickens brings you here?”

Perhaps her piquant face asks the same question, for after a little he suggests: “This meeting is unexpected to you, Miss Minturn: you now discover what I meant by au revoir at Delmonicos.”

“Why—I—I had supposed you were bound for Paris,” says Louise.

“No. My brother goes to France with Miss Severn and Mrs. Dewitt,” answers Larchmont, looking serious.

“Then you are en route California, I imagine?” asks the girl a little anxiously.

“Only as far as the Isthmus.” The young gentleman does not look very happy as he says this, and astonished meditation comes over the young lady. This bird of fashion might run away from winter in New York to the orange groves of California, or to gay St. Augustine, or the Riviera, or even Egypt: but why should Harry Larchmont make a pilgrimage to Colon and Panama, with their swamps, miasmas, and yellow fever? She is sure of one thing—that it is not for pleasure. She recollects that he sighed when he said, at Delmonico’s, it might be the last time he would lead the cotillon.

He affords no solution to the problem, though he gives the young lady several pretty commonplaces, and the conversation at the table runs along in a desultory way: but it is a conversation that delights the girl who is listening to it. She perceives the narrow limits of Miss Work’s typewriting room have opened, and let her pass out into the world of finance, of politics, of diplomacy—the little world that dominates the greater one. As she thinks this, the girl’s eyes grow bright with excitement at the new life that is coming to her.

Across the table from her a discussion is taking place as to whether the United States will interfere in case the rights of the few remaining American stockholders of the Panama Railroad are ignored by the Panama Canal Company that has purchased it. Colonel Clenghorn Cleggett is apparently the most bitter Gaul in the discussion, and is verbally trampling on his own countrymen with savage vehemence.

“Rather an unAmerican chap,” remarks Mr. Larchmont sotto voce to Miss Minturn. “According to his own stories, Cleggett was a Congressman, and yelled Monroe doctrine until he received a French appointment.”

“Then he is a mercenary traitor,” says the young lady, with the quick decision of youth and womanhood, in a whisper that brings her pretty lips very close to Mr. Harry’s ear, for their seats at table permit easy confidence.

A moment after, she suddenly goes on, “How much you know about the Canal!”

“I’ve been making a quiet study of it lately,” answers the young man, and rather gloomily attacks his breakfast.

Then silence comes over Mr. Larchmont. Having come in late to breakfast he is apparently making up for lost time, so the young lady could keep her ears open and her mouth shut, did not the captain’s occasional attentions compel reply.

He insists on her tasting the various dishes he recommends: and knowing the strong points of his cook, she discovers she has fared very well by the time the skipper rises to leave the table. The young man beside her is just finishing the last of his coffee hurriedly, and is apparently about to address her, when the captain, offering a gallant arm, says: “Let me show you my ship, Miss Minturn”: and with that seizes upon Miss Beauty, and takes her up the companionway, to instruct her in various nautical matters.

After a few minutes, the captain’s attention is demanded by his first officer, and Harry chancing to saunter out from the smoking room, the seaman turns his charge over to him, saying: “My boy, complete my instructions. Miss Louise now knows the difference between a top mast and the smokestack.”

Then going away to his duty, he leaves the two facing each other.

The gentleman looks pleased and eager. The lady’s eyes turn to the water, as it flows past, a slight blush on her fair cheeks, a little confusion in her eyes. She is thinking of the blizzard and—the violets.

Mr. Larchmont says laughingly: “Miss Minturn, since you have been under the captain’s instructions, will you please educate me?”

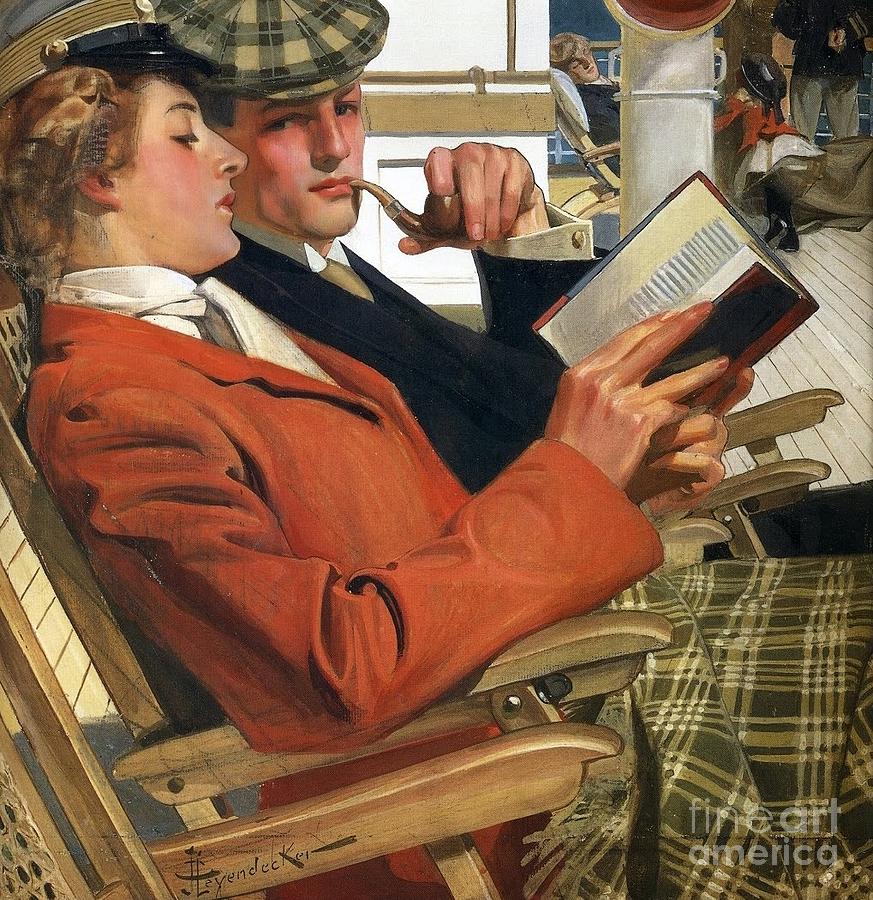

So they shortly find themselves seated in two steamer chairs which the young gentleman, for some occult reason, has placed very close to each other.

“What a languid sea breeze!” murmurs the girl, making an alluring picture of laziness as she dallies with her white parasol.

“Not as languid as the blizzard,” laughs Harry.

Whereupon the young lady turns on him grateful eyes, and whispers: “You were very kind to me!” then looks over the water.

“Ah! you like me in the rôle of rescuer?” returns the gentleman, suggestion in his voice.

“On shore, perhaps: but here your remark indicates collision, hurricane, shipwreck, and ‘Man the life boats!’” replies Louise, growing a little pale at her own imagery. Then she suddenly ejaculates, “What a pretty little ship!”

“By Jove!” cries Larchmont, hastily producing his field glasses, and inspecting the pennants of an exquisite schooner that is just abreast of them, with every white sail set to the southern breeze.

“Why, she looks like a toy compared to our steamer!” remarks the young lady: and noting the gentleman inspecting her signals, continues: “You appear to know the boat.”

“Yes, that is the Independent, Lloyd Pollock’s schooner yacht,” answers Harry. “Pollock is bound for the West indies, for a winter cruise. He is one of the most charming ‘do-nothings’ in the world. He spends his life seeking summer.” Then he sighs, “Two months ago I was a ‘do-nothing’ also.” This last remark is perhaps produced by the sight of the steward serving cocktails on the yacht’s deck.

“Well, why not join him?” suggests Louise. “Mr. Pollock is a friend of yours?”

“Yes, an intimate.”

“Then hail him. He is hardly too distant, even now. Ask him to take you on board,” continues the girl, who is a little piqued at her companion’s sigh. “Your trip to the Isthmus does not please you.”

“I am better pleased to be here than on board any yacht in the world,” answers young Larchmont stoutly; and looking upon his companion concludes that he has spoken the truth. Then a new idea seems to come into his mind, for he goes on suddenly: “You are journeying to California, Miss Minturn?”

“No,” says the girl, “what makes you think that?” and turns wondering eyes on him.

“Why,” he answers, a little hesitation in his manner, “I had heard a young lady on board was en route to California to be married. When I saw you at the captain’s table alone, and in his charge, I presumed you were the fiancée.”

“I am not going to California, and I am not going to be married!” utters Louise decidedly. “That young lady”—she indicates by her parasol Miss Madeline Stockwell, who is seated by the side of a young Costa Rican—“is the coming bride.” Smiles are upon her fair face, for she is glad to find Harry Larchmont has been speculating upon her. She laughs, “Could you not tell it? I thought brides could always be guessed.”

To this the young man replies: “If brides could be guessed by tremendous flirtations, I should have selected Miss Madeline Stockwell. How do you think her fiancé would enjoy looking on that?” and he points to the Costa Rican, who is stroking his moustaches with one white hand, and with the other devotedly fanning the pretty Madeline, as she sits languidly on her campstool, a picture of contented ease, apparently having forgotten the orange grower.

Then the two become merry, for somehow Mr. Larchmont’s face, when Miss Louise had announced to him she is not the coming bride, has given that young lady good spirits. So they go to joking with each other, and have quite a merry time of it, until Harry brings catastrophe upon their tête-à-tête.

He says incidentally: “By the by, Miss Minturn, you remember that gentleman who was with you at Delmonico’s the other evening?”

“Oh, yes!” she replies carelessly. “Mr. Alfred Tompkins: he came down to bid me goodby.”

“Then it was he!” ejaculates Harry, a peculiar look coming into his face. “He is a very curious man.”

“Indeed! Why?”

“Why, he ran to the end of the dock just as we cast loose, and shook his fist at the ship, and called out, ‘You infernal scoundrel!’ For a moment I wondered if he was not anathematizing me: but a French gentleman standing beside me took it to himself, and crushed your friend with a volley of Gallic invective. Consequently, I know he did not refer to me.”

There is meditation, yet questioning, in his voice: perhaps there is a little roguery in his glance: for the young lady has turned suddenly away, and a big blush has come upon her. She knows the reason of Mr. Tompkins’ violence, and in her heart of hearts is gasping: “Good heavens! he thought I was eloping with—if Harry Larchmont should ever guess!”

A moment later, the gentleman startles Miss Louise again. He says: “You are not a good sailor, I am sorry to see.”

“Why?”

“Because every little lurch of the vessel seems to make you wish to look over the taffrail. Besides, you were sea sick in your cabin for three days.”

“No, I was not!” replies the girl indignantly. “I—I had some writing to do.”

“Ah, then you are a good sailor. You like yachting, of course?” This is said as if everybody yachted: and Louise bites her lip, and hates him for making her confess ignorance of that fashionable amusement. Then great joy comes to her. She remembers the catboat Tompkins hired in summer, and called a yacht. She had been on it once at Sheepshead Bay, with Sally Broughton, and putting her soul in her words, she answers sweetly: “I adore yachting!”

Then she grows very angry again, for he has glanced at her surprised.

A moment after, he goes on, unheeding indignant looks: “If you adore yachting, and I love yachting, suppose we imagine this ship a yacht: we have yachting weather.”

” What difference,” says Miss Minturn petulantly, “does it make whether we consider are on a steamer or a yacht?”

“Only that on yachts people get better acquainted with each other. There is something in the very deck of a yacht that makes people feel épris.”

“We will consider this a steamer,” mutters the girl piquantly yet sternly.

Her glance disconcerts the young man: but he says: “You play, I know.”

“Passably.”

“On the piano?”

“Yes, on the piano, the guitar, banjo, and harp. My mother was a music teacher.”

“The guitar—you have one with you?”

“It is in my stateroom.”

“Then we will have musical nights on deck: dancing waves—romantic moonlight—the——”

Harry’s eyes are speaking as well as his lips, when Miss Minturn cuts him short with, “My evenings are devoted to writing.”

“Oh, letters for home?”

“No, my diary.” As this slips between the young lady’s pretty lips, she clinches her teeth together, as if trying to cut it off, and grows very red, for he is whispering: “A diary! a young lady’s diary! I am devoted to such literature. Give me a peep at yours?”

“Oh, gracious!” ejaculates the girl, for sudden thought has come to her: “If he should see it with his name on every other page!” Very red, but desperately calm, she goes on: “That diary is under lock and key, and shall remain there. No one will ever see it.”

“Not even your husband—when you marry?” suggests the gentleman.

“He less than anyone!”

“Of course not! The diary would be very sad reading for the future husband,” answers Harry, putting pathos in his voice. Then he says consideringly: “I am glad, however, it is a diary. Diaries can be left till tomorrow. I was afraid it was some of that awful stenographic work: that I might hear the click of the typewriter in your stateroom.”

“Typewriters,” cries Louise, “are for the Isthmus.”

“For the Isthmus?”

“Yes. Don’t you suppose there is any business done on the Isthmus?” answers Miss Minturn, with savage voice: thoughts of typewriters do not charm her soul this pleasant morning. “Is the Panama Canal all talk and no work?”

Now this latter announcement seems to have a very potent effect on the gentleman with her. He mutters: “I am afraid so.” Then continues: “I am going to the Isthmus myself, on business—business on which——”

Here Louise eagerly interjects, delight in her voice: “So am I! I am going out to be the stenographic correspondent of Montez, Aguilla et Cie.”

At these words Harry Larchmont starts, looks at his companion with sudden scrutiny, perhaps even suspicion. A moment after, apparently changing the tone of his speech, he says, with an attempt at a laugh: “So am I.”

“What! Stenographer for Montez, Aguilla et Cie.?”

“No, not exactly that, but I am going to be a clerk also.”

“You a clerk? You, who have led cotillons? You, who are one of the lazy birds of the world?” gasps the girl, astounded.

“That is a thing of the past, now,” he says contemplatively. “You see,” here a sudden idea flies into this gentleman’s mind, and he becomes apparently confidential, “when a man in the class I have been running with discovers, to put it pointedly, that he is ‘dead broke’.”

“Dead broke?”

“That’s what I said. He finds very few avenues of employment open to him that are sufficiently lazy to suit his disposition.”

He makes the last pictorial, by reclining very languidly on his steamer chair, and murmurs, “You look happy at my news.”

“Happy?—I—” stammers the girl. “Of course not!” But her eyes belie her words, for there has flown into her soul a rapturous thought: “This man and I are now equal in this world’s goods.” After a moment she goes on suggestively:

“Why, you might go on the stage, with your voice and figure.”

“Thanks for your compliment!” he laughs. Then, growing serious, says: “On the stage! Every dramatic jackal of the press would have run me down in their columns as coyotes do a buffalo that has left his herd. Besides, do you think a man becomes an actor without study? And I have never studied anything.”

“Why, you must have studied something—football for instance!” laughs Louise. Then she says, her eyes growing large with admiration: “I saw your wonderful game four years ago.”

“Yes,” he replies, “I am an athlete, but not a prize fighter: prize fighting leads to the stage, not general athletics. Consequently,” he goes on, as if anxious to stop discussion on this point, “I applied to my uncle, Mr. Delafield, who has some influence in business circles, and he has obtained for me a clerkship in the Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s office at Panama. I think it will suit me. They only have three steamers a month: between times I can lie in a hammock, smoke cigarettes, eat oranges, and suck mangoes.”

“Yes, I think it would suit you,” says the girl mockingly: and looking at him, acquiesces with him, but does not believe him. His speech seems to her not genuine. Up to the time she had told him she was the correspondent for Montez, Aguilla et Cie., his conversation had been frank and ingenuous: from that time on, it has appeared to be forced.

A moment later the captain breaks in on her meditation, saying: “Harry, I think we’ll have to change watch now. It’s my turn below.”

And Mr. Larchmont, to whom this conversation has grown embarrassing, for he is not a young man to use ambiguities easily, and tell white lies with the straightest of faces, but who feels it necessary to disguise the reason of his visit to the Isthmus to anyone connected with Baron Fernando Montez, yields up his seat, and strolls off to meditate over a cigar.

Then the captain attempts to make play with the beauty of the ship, but finding her unresponsive to his nautical wit and humor, suggests lunch: for she is thinking, “If it is true? If he is a clerk—there is no gulf—Harry Sturgis Larchmont and I are equal before the world!” And it is joy to her, for this girl loves the man, not his reputed wealth or social position.

So the day runs on, and Louise gets to watching this young man who has been so much in her thoughts, and what she notices makes her wonder still more.

There is a certain Carl Wernig, a gentleman who the captain tells her is of prodigious wealth and great influence in the Panama Canal Company. This person seems to be interested in the movements of Mr. Larchmont. The two having picked up a hurricane deck acquaintance, Miss Minturn hears him mention to Mr. Larchmont that he knows his brother Francois in Paris.

“I call him Frank,” says the New Yorker rather curtly. “An American name is good enough for me, though I believe my brother has Frenchified his since he has been promenading the boulevards.”

But nothing seems to check this German in his interest in Mr. Larchmont. He joins him, at every opportunity, on deck, laughingly questions him as to his trip on the Isthmus, as if anxious to know what he intends doing there. To these Herr Wernig receives the short answer that Harry is “busted,” and is going out as a clerk to Panama.

The next morning, Miss Louise, who has spent some part of her night meditating upon the gentleman of her thoughts, gets a surprise when she comes on deck and stands by the captain’s side, looking at the Island of Salvador, with its white lighthouse.

The skipper says suddenly: “By Jove!”

“Why do you make such extraordinary remarks?” asks the young lady, a little startled at the bluntness of the seaman’s exclamation.

“Why, look at that young springall, Harry Larchmont, sauntering along the deck as unconcernedly as if it were an everyday occurrence: and yet I understand Mr. Cockatoo lost one thousand dollars at poker last night! Those young bloods think the skipper does not know what is going on in this ship, but the skipper does.”

To this Louise does not reply. A curious problem is in her mind. She is wondering how a man, who yesterday told her he was “dead broke,” seems not even to give a passing thought to the loss at cards of one thousand dollars that will be “hard-earned dollars” to him very soon.

As she goes down to breakfast she thinks: “Can it be the carelessness of financial despair, or is it from force of habit?”

She had known Larchmont was regarded as rich, even in New York, where a million dollars goes not over far. Is this exile from the Four Hundred, though he has not gone on the stage, acting some part? Does he wish the real object of his journey to the Isthmus to be unsuspected and unknown?

Notes and References

- patois: (French) a rural or provincial form of speech.

- sawbones: a surgeon or physician

- sotto voce: (French) soft voice

- rôle: 1600–10; <French rôleroll (as of paper) containing the actor’s part

- taffrail: a rail above the stern of a ship

- catboat: a boat having one mast set well forward with a single large sail

- épris: (French) love

- springall: a diminutive of “Spring,” as in a nickname for a “lively young man.” http://www.houseofnames.com

Broyles, S. ,’Vanderbilt Ball—how a costume ball changed New York elite society‘. Blog, Museum of the City of New York.

Morrow, A., ‘New York’s Other Monicker‘, Historynet.

‘Vanderbilt Ball’ – New York Sun 29/03/1883. NY City blog, PDF.

‘Vanderbilt Ball’—New York Tribune 27/03/1883. PDF.

‘The Four Hundred‘—edwardianpromenade.com

This edition © 2021 Furin Chime, Brian Armour

Categories: A.C. Gunter: Baron Montez of Panama and Paris