Glenorchy Royal

Let us regress a few weeks, before the scene at the homely Junction Hotel. Before the discovery of the headless body. Before any names were written down, even in a dog-eared notebook. The world barely notices such half-invisible men until a cause arises to record them – for all their swagger. This was before all that, when they strode unhindered and unsought. Dust clung to them, and their deeds had not yet congealed into fates. Glenorchy manifested itself lazily as they approached: a post fence, a dozing kelpie mix, the tin flash of a roof. The Royal Hotel waited in the heat, half-slumped, only half-aware.

“This is a hellish, God-awful, melancholy town. The miserable bloody air here alone is enough to make a cove want to get rotten,” Burns said, dispensing with his hat and scratching his head. Truth was, he was feeling tolerably well, buoyed by the promise a day held that commenced with a bout in the Glenorchy Royal Hotel, renowned as it was in the district for its unadulterated grog. No fig tobacco in the brandy casks here, cobber. And the publican’s daughters are good sorts, too – said to cut out a stubborn bullock as good as any plains stockman. The publican knows everything about anything, by all accounts, including, perhaps, the lay of the land. But it turns out he ain’t here. Joseph Jenkins, the self-styled “part proprietor,” has charge of the place today and is big-noting himself on the strength of it.

A hollow masculine chorus echoed in the bar – voices of shearers, farmhands, bullock-drivers – out of which one solo strain or another might ascend now and then, distinct enough to catch scraps of individual wisdom: the blowflies, the heat, a dog’s virtues, or a horse’s ailment. The most vocal, a couple of ancient farmers at a table by the front window, were bemoaning rabbits.

“Official work to do, Scotty,” Burns said. “No good to be drunk as fiddler’s bitches.”

“Why bullock our guts out? Like my old man used to say, never put off till tomorrow what you can do the day after. A spell of easy drinking will give us zest for the task. Don’t take much, anyway, to find out where the lots are, chuck up a couple of pegs and notices.”

“Back here by late afternoon for cards and hot whisky anyway.”

“You’ve already got a good start on it, mate.”

But Burns called the barman over and ordered four tots of rum for a heart-starter.

“Me and me mate’s got a thirst on after a’rambling place to place for work, which we’ve been doing in the hearty manly fashion, in the spirit of comradeship that is the pride of the Australian bush,” he said – in a forced jocular, theatrical tone that, boorish as it proved generally to most audiences subjected to it, he knew would draw a guileless grin from Forbes.

“Soon to be landowners,” Forbes said. “Proper cockies, us!”

Burns inquired of the barman:

“Would you mind fetching us some of the more recent volumes of your collected publications, my good fellow – any sorts of broadsheets, gazettes, whatever journals have informed and entertained your distinguished clientele.”

Then turning to his companion:

“Must keep track of world affairs, when you’ve got your head in a hole in the ground half the time, old man. See how the Australian Eleven are going over in the old Britannia, and so on and so forth.”

“Oh yes, God almighty!” Forbes let go a cracking belch that silenced the bar for a moment, and the two roared madly, Burns holding his stomach and shaking his head.

When the barman returned with their nobblers of rum and some newspapers, Burns raised a hand as if to prevent Forbes from paying and produced two shillings from his money purse. “It’s what a bloke does for a good cobber, who’s a half decent sort,” he said.

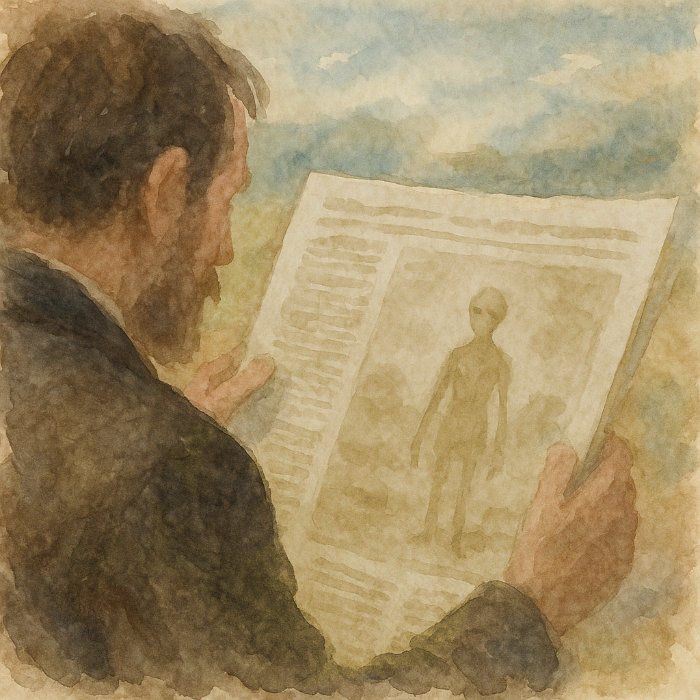

Forbes threw his head back from his paper, then tapped it three times with his index finger to mark the rhythm of his utterance, as if to emphasise its gravity.

“I bloody well knew it! People on Mars are no bloody different from us here on Earth.”

“What is that nonsense?” Burns said, glancing up from a cricket report.

“Not nonsense, mate, The Australian Town and Country Journal, scientific notes. It’s not as bright as it is down here, but their eyes are more sensitive, so they can see just as good. The polar snows extend further, so it’s colder, you know, naturally, but by no means less in proportion to the lessened power of the solar rays – so, anyway, make of that what you like.”

“Fuck me dead,” Burns said.

“This Professor Lockyer – or some what’s-his-name or other – has discovered several remarkable seas in the southern hemisphere, including inland seas, some of them connected and some not connected with the larger seas by straits. One of their seas looks exactly like the Baltic, and there’s an equatorial sea, a long straggling arm, twisting almost in the shape of an S laid on its back, from east to west, at least 1000 miles in length, and 100 miles in breadth.”

Forbes shook his head slowly and mused through the window towards outer space.

“Let’s have another rum. That reminds me, we need some S-hooks from the blacksmith’s, for sinking them dams in Dunkeld.”

When the barman served them, Burns was again magnanimous in paying.

“Why do you say that every time?” Forbes said.

“What?”

“All that deal about paying for your mates. I’d take my turn just as quick, except you’re holding all my dough.”

“What?”

“Nothing.”

“And why would that be, do you reckon?”

“What?”

“Why am I holding your dough for you, do you reckon?”

“So as I won’t chuck it away on cards?”

“Or pour it down your gullet, right? Look here, if you want to hold it yourself, you’ve only got to say so.”

“Ar, it’s alright, you go on holding it.”

“No, no, here you go, have it bloody back, because I know what’s going to happen.”

“No, it’s alright mate, you hold it. You hold onto it for me.”

“No,” Burns said, raising his voice as he bent down to undo his swag, lying on the floor by his boots. “If that’s how you feel about it, you take it, and we’ll wait and see what happens.”

He fussed around, unable to lay his hand on the stash immediately, testily disembowelling the swag. The bar now quiet, furtive eyeballs over nobblers of whisky hot. Strange ones.

“Don’t worry about it, Bobbie” – Forbes pleading – “I’m sorry. You look after it for me, please mate.”

Burns’ back and shoulders slumped as he sighed, tut-tutted, shook his head, sat up, leaned back.

Pause.

“Ah, Scotty, what are we going to do with you, son? I know you’re a good’un right and proper, but god you make it hard to look after you sometimes.”

Weary head shake.

“Sorry mate, sorry.” Forbes placed his hand on the back of his mate’s wrist, and the two men looked each other in the face. His eyes watered, a teardrop forming at each inner corner. Conscious of it enough not to sniff, he looked into Burns. A kind man, tough but kind, good to me. His eyes, well, there was a trace of softness to them. Like his beard, bushy but soft. Burns could see right into him, too; he could see that much. They had shared tender times together, which was not the usual lot of those thrust together in railway camps. Forbes sought a salve of kindness in his eyes, the closest thing he had known to affection for a long time – who knows? – for his whole life long.

Day moves along, and the rambunctious hour draws near. Patrons who’d started at half past ten in the morning are caught up by tardier arrivals, spurring themselves on to comparable states of elation.

At some point, a mob of navvies crowd round the old farmers and begin to ply them with whisky for sport. Taking a barrel or chair for a seat, the hands share the one table, while one or two stand leaning against the wall engaged in their own conversations.

“Bloomin’ city so-called ‘sport shooters’ brung ’em over from the Old Country, and the sparrows and deers and all. Said in the paper, if we got rid of the vermin, they’d get even more. Bloody Wild Rabbit Propagation Committee, would you believe?”

“Don’t tell me!” yells a hand, hawks and hacks in his pocket-rag out of politeness.

“I’m telling you, my son,” says the old red-haired feller, “It’s bad enough now with the rabbits, but in the sixties, them damn vermin was so many, you’d go to pull out spuds and find they was rabbit nuts instead!”

“You don’t say!”

Hoots and hollers. “What’d you do with the rabbit, mate?”

“Well, you threw it out and chucked the balls in the broth for veggies. No one was in the mood for rabbits no more, in no shape or form, I’ll tell yer that much.”

“Didn’t the government do nothin’ about it?”

“I tell you what,” says old red-headed bloke’s mate. “I’ll tell you right now all what the guvment’s good for. Bloody nothing. A year ago they come up here, these blokes, an army of them got sent by the guv’ment. Half a dozen Melbourne loafers and twenty-eight mongrel dogs! They went into a district so thick with pests that hundreds of men, women, and children had worked day and night for months with dogs, guns, and traps – and still made no impression. So we laughed our guts out at these poor bastards running around with their dogs. Not worth a tinker’s dam, them blokes. And sure enough, the dogs tired of huntin’ rabbits and thought they’d prefer worrying the sheep, and the local inspector took out a writ against these bastards for having unregistered dogs!”

A gust of laughter rips through the heat – “God Almighty!” – “Don’t tell me!” – “You’re havin’ us on, y’old bugger!” – “Bloody hell, so who was the vermin after all, eh?!”

Misshapen dwarfish gargoyle Poor Joe the Ostler is all unbridled mirth. Lets loose an ear-splitting hoot, perching upon his stool. Leaning next to him, kindly Tom Piper, who was once a prize-fighter, stands Poor Joe another, but will keep an eye on him.

“Goin’ to have a wee jig, Joe?” lisps a vile flea called MacDougal, peering across Tom Piper’s face, up to mischief. Poor Joe’s drunken antics are a thing to behold.

“Do you want to find yourself out there on your face in that muck-heap, MacDougal?” Tom Piper is not one to waste words, and MacDougal slurps quietly, before seeking less perilous entertainment.

Old red-headed bloke’s mate. “An imbecile from Warrnambool invented some kind of pills to poison them rabbits, and them pills did work to great effect for sure when a rabbit ate one, but hardly any of the rabbits did. Weren’t to their liking. God’s blood! We tried destroying them, filling their burrows with poisonous fumes, but that was damnable hard work, and we didn’t know where half their burrows was. It’s a nightmare, as you can well imagine!”

Burns sorts the accommodation.

Pencil poised, the barman assumes: “Two rooms?”

“Just the one, son. He’s too far gone to warrant a room his own. I know him. I’ll have to look after him later.”

“Who’s paying?”

“I am, for sure as lookin’ at me, see this roll I’ve got here!”

The barman looks him in the eye – a flicker of recognition there, and maybe a hint of suspicion.

“Come on, cobber, I’ll see you an extra couple of bob.”

Something in the barman’s smile twitches – almost salacious, or maybe just the beer – but not enough to call it a leer. And Burns missed it anyway.

“If you say so, mate. Two bob, ya reckon?”

Forbes mingles, spreading his innocent masculine charm, and generally the locals take to him. Burns has passed him enough dough to stand a few rounds, and he is liberal with it. Here is the single theatre where he can demonstrate the largesse that he aspires to be known for. In return, you have to lend him your ear to chew on for a bit.

“Who are you, my good man, and what’s your game?” says Forbes to an amiable fellow

“Archibald Fletcher. I work for Stawell Council as a road overseer.”

“Well, Archy, I wish to have a word with you. Who is that gentleman over there with the long white coat? He insulted me about my church, my creed, and my coat, and I will not take that from any man! Not him nor you.”

“I see no such chap.”

“Do you think I’m stupid, do you? You might be surprised to hear that some fellow in England has made a remarkable invention called ‘captive daylight.’ Did you know that, smart-arse?”

“And what might that be, Scotty?” Burns sidles up, winking a cold wink at Fletcher, the council road overseer.

“What it sounds like, mate, just what it sounds like. I read that this chap, a Mr. Balmain, I think his name is, if memory serves, has succeeded in producing a luminous paint which can absorb light, as it were, and during darkness will suffice to illuminate an entire apartment. Very interesting article.”

“My lord! That will be good for the outhouse!” Howls from those in earshot. “Yeah, good for readin’ the paper in the dunny without no candle!” Further rustic, scatological expressions of humour.

Fletcher moves off, as the others incline an ear.

“Yes, well, indeed, some might suggest there are those dimwits who can’t get their minds out of them parts! Anyways, they’re going to use it in compartments on board ironclads, probably. It’s quite intelligent, really,” Forbes says.

“How would you turn this paint off when you wanted to go to sleep?”

“Well, I don’t know, I suppose you don’t need to sleep in the dark, does you?”

“A lot of blokes don’t like to sleep when the room’s all lit up, like. I’m one of them myself, in fact, so it seems to me there are apparent drawbacks with this invention.”

“I can assure you as some folks would prefer to read late into the night, save on the price of oil at the same time, and pull the sheet up over their head later.”

The laughter swells around them, voices breaking off into pockets of side talk. Burns drags a barrel up beside Forbes and leans close, his mouth near the other man’s ear, speaking gutturally against the racket, passing on what Jenkins the barman calls good oil on the allotments of land up for selection. There’s one or two up this way, not far from the river, which at this time of year has dried up into a line of muddy water holes, but there’s some better ones closer to Stawell, too. Blow going all the way down there today; best to catch the train there tomorrow or the day after. Cast an eye over the ones up here first. Bit of a walk this arvo. Then go down to Stawell by rail. You can meet the missus and kids.

They down two more solid nobblers of rum apiece, before following the route Jenkins’ map takes them on, out of town and north-east towards Swede’s Creek. Forbes has procured two flasks of brandy with what is left of the money Burns has given him, and they alternate swigs, while Burns elaborates on his vision of their shared future as wheat farmers. For the most part, Burns will live with his wife and six children in Stawell, and Forbes will occupy a house on the new property. They stop at the weir for a smoke and gaze down at the muddy trickle way below. Burns lets drop the empty flask, which comes to rest with its mouth barely above the surface, such that suddenly the waters eddy in, until it emits a comic gurgle and disappears.

Burns knows more than enough about farming, he reckons, to put Forbes on the right track. There are two classes of selectors – one goes on the land without money, and the other without knowledge; and there are some who go on the land without either. But of the first two, he would rather give credit to the man who lacked money but possessed knowledge than he would trust the man who had a limited supply of money and no knowledge at all. Did you know, mate, that sailors make the best selectors? The best of non-farmer selectors, that is. They are quick-eyed, active, strong-handed, and excellent judges of the weather. They can, he opines, almost without exception, successfully compete with old hands in fencing land.

Four bottles of water? asks some bird invisible in the bush, the phrase clear as speech.

“Well, I sure ain’t no sailor neither,” Forbes admits, in a tone that one would not quite call wheedling as such, though a kind of seeking for self-reassurance is evident in it, some murky undertone. “I think I might have my work cut out,” he says with a self-deprecating smile.

“Tosh! you will do alright, son,” Burns says with a wink and a slap on his mate’s shoulder. “Well, I have to say the land’s not much good around here. Only fit for a sheep walk and a poor one at that. You’ll find a sheep every five acres around this place at best.”

They continue their trek for a while, Burns examining a clod of the friable clay here and there, until the second flask is emptied. “Not too heavily timbered around here,” Burns observes, taking a final swig and tossing the flask. “Just a few patches of bull-oak – though that’s useful stuff for building.” Belch. “The creek’s not always like this, you know, just waterholes. It fills up alright, and I heard some talk back there about some sort of irrigation scheme that might come through in a while.” Snort, hack.

“Listen to them birds,” Forbes says with a giggle. “They’re saying the same thing over and over and over. What sorts of birds is they?”

They stop still and listen. A long silence. Then … CRACK! Click-click-click!

“Out here? Must be lost,” Burns mutters of the Eastern Whipbird.

Four bottles o’ water – watchya baaaack!

“There he is!” laughs Forbes – a flash of sheer, foolish delight. “Four bottles of water!”

“They’re not talkin’, just skwarkin’, son.” Burns’ patience thins. “Will you listen to what I’m saying to you, for Chrissakes?”

Forbes is still looking up into the branches, laughing.

Burns exhales, the sound more growl than sigh. A shadow seeps into his gaze and his jaw tightens.

Cackling, Forbes mimics some more, then falls silent, listening. Burns spits, thinking. Here and now, God help me, I could kill him.

As they go on, Burns lags behind, wobbling his head, sneering, and mouthing Forbes’ words in a sarcastic pantomime.

They arrive back at the Royal. Forbes takes some brandy and old newspapers up to their room and pores over some articles of passing interest, though his brain is unable to comprehend much of what his eyes admit into it: The necessity of employing very intense temperatures in cremation, so as to convert the body into ashes, appears likely to be done away with by the experiments of M. Lissagarry. The difficulty in cremation is to decompose and reduce to ashes tissues containing 75 per cent of water; but M. Lissagarry overcomes this by exposing the body, first of all, to the action of superheated steam, which chars the tissues and enables them to burn easily in an ordinary simple furnace at a very much less cost of fuel and without the least unpleasantness . . .

He blinks slowly, reaches for the brandy, and lets the print swim before his eyes, the words dissolving into the paper’s yellowy grain. His lips shape the words soundlessly. There are some hard ones, but Bobby will know what they mean. He always knows. Rolling onto his back, arms askew, Christlike, he drops into unconsciousness. Snores like ballast pouring into a hopper. Dreams a dream of a sky fretted with magpies, wings beating over acres of land littered with skeletons.

Tom Piper steers Poor Joe, incoherent, out the back to his mat of hay in the stable. Off he totters, and Tom returns to the fray.

Burns throws himself into a chaotic game of three-card loo in progress in a smoke-filled room adjoining the bar. Six men compete for tricks around a dilapidated table buried under piles of coins and damp clumps of notes, while onlookers crowd in to outshout each other’s wagers. In the main bar, an accordion strikes up an off-key melody, an Irishman belts out an amorous ditty, forcing the instrument to conform. Then a polka, and a few dance in pairs, man on man, stiffly wobbling around each other like toy peacocks, leaning away, gripping each other by the elbows. Only one woman is present, and she is too far in her cups, anyway, to be of any use, engaged in a slurring interchange with a navvy at the bar, though their topics are unrelated, and they speak past each other’s eyes.

Burns’ cheer curdles as his luck rots. Repeatedly ‘looed,’ he feeds the pot, three at a time. Others scoop the winnings while his pile shrinks. The pool swells. Greed thickens. The drink works deeper with each loss, peeling him down – the drunken, belligerent aggrandising become brutish, to reptilian – to a being older than men. His hands move more slowly now, eyes narrowed, as though weighing the other men for more than their cards. A primitive thought coils, half-remembered, half-whispered by something older than his bones, shedding centuries like skins – as though a presence that had slithered through ages of darkness might, on a vicious whim, infect a human soul.

After the fun, Jenkins the barman is left to sweep the refuse into piles on the floor. He leaves the doors open for the last curls of tobacco stench to drift out with the nocturnal breeze. The place is otherwise empty except for Burns – or rather, what’s left of him. The man-shape slumps in the chair, but the thing inside is pared back to its oldest layer, the cold-blooded remnant that survives when all else is stripped away. His gaze is hooded, face sliding off the skull, mouth agape and drooling. A slow flick of the tongue, lizard-like, tastes the air.

When Jenkins has finished sweeping, he leads the creature up the stairs. By the top step, Burns is down on all fours, almost slithering. “Here you are, mate,” Jenkins says at the door. “Allow me…” He turns the master key and ushers the creature inside. From somewhere far back in his skull, Burns watches this with cold detachment. When he spits, his saliva oozes in strings to the floorboards. He tries littler ptuh! ptuh! spits to be rid of it, but it clings there.

Leave a comment