Document 17: Manifestation Series

The unicorn is injured, why did it come? My way is finished.

⁓ Attributed to the Zuozhuan, on the death of Confucius, 479 BCE (adapted)

This account, drawn from the lower ledgers in the Registry of Misperceived Wonders (Third Vault), concerns the imperfect ascent of a crown, a sign mistaken for itself, the brief elevation of a foreign scholar, and a haunting sigh. The report commences with an account of the journey of the foreign envoy from the White River, just south of Tongzhou, to the Forbidden City. The route is as well-trodden as the tropes that embellish it, so for present intents, the passage has been elided.

Lord Macartney received with restrained annoyance the news of the extension of his itinerary a further 160 miles, extending the journey into Tartary. He was already preoccupied with the Chinese administration’s requirement that he perform full-body kowtows to the Emperor, since he was not required to humble himself in this way even before his own monarch, good King George III. He nevertheless resigned himself to attempting an approximation. Bright Yang set him at ease with a broad smile and copious applause, assuring him that his impromptu flourishes, bows and scrapes such as he demonstrated, which were worthy of the most extravagant dandy, would more than satisfy the Qianlong Emperor, who was, in any case, a most amiable fellow once you got to know him.

Lord Macartney, an Ulster Scot consummately qualified for ambassadorial duty, departed from the capital with the majority of his entourage, leaving behind much of the valuable equipment that he had dragged to the ends of the earth as presents for the Emperor, in the care of his tiring – in both senses – travel companion, another Scot: astronomer, physicist, inventor and philosopher, one dour James Dinwiddie.

One of the marvels intended to evoke the amazement of the Chinese Emperor was a clockwork planetarium of Dinwiddie’s own devising, which had taken him thirty years to build and was acclaimed “the most wonderful mechanism ever emanating from human hands.” Dinwiddie’s second love among the collection of marvels was a hot air balloon, an “aerostatic globe” of his own design, with room for two aeronauts. Although he had never gone aloft in one before, which had proven to be a perilous feat throughout Europe, he had become obsessed with the idea of becoming the first to do so in China, and to float high above the Emperor, his court, and the citizenry of Peking, who would all be rendered agog in disbelief. Such would be his historical legacy, he foresaw: even above his planetarium and extensive philosophical tracts, it would be foremost amongst his life’s works.

Other items in the display included reflecting telescopes, burning lenses, electrical machines, air pumps, and clocks; brass artillery, howitzer mortars, muskets, and swords; a diving bell, musical instruments, magnificent chandeliers, and vases; Wedgwood china, paintings of everyday English life, scenes of English military victories by sea and land, and royal family portraits. The cost amounted to fourteen thousand pounds – in those days a formidable sum.

On the journey to Peking with the envoy, Sun Pu-erh took stock of the information she gathered and started a series of detailed sketches of the devices most relevant to her Emperor’s wishes, in particular the military and scientific machines and artefacts. She employed spies and draftsmen to aid in the task. Bright Yang, on the other hand, was absorbed in tales that had flourished among the populace as the envoy made its way up along the White River – tales in which, perhaps, the twelve-year-old son of Lord Macartney’s secretary had a hand, aided by his smattering of Chinese. From the point of view of the child, similar to that of the rural populace in this regard, the official inventory of planetarium, lenses, lustres and so on, was not overwhelming, hence stories grew up that hidden inside the cargo were the actual marvels to be revealed to the Emperor: an elephant no bigger than a cat; a battalion of miniature, living British grenadiers, each only twelve inches tall but perfect in the most minute detail, down to fingernails, eyelashes, and intelligence; and a magical pillow that transported one to faraway countries while one slept.

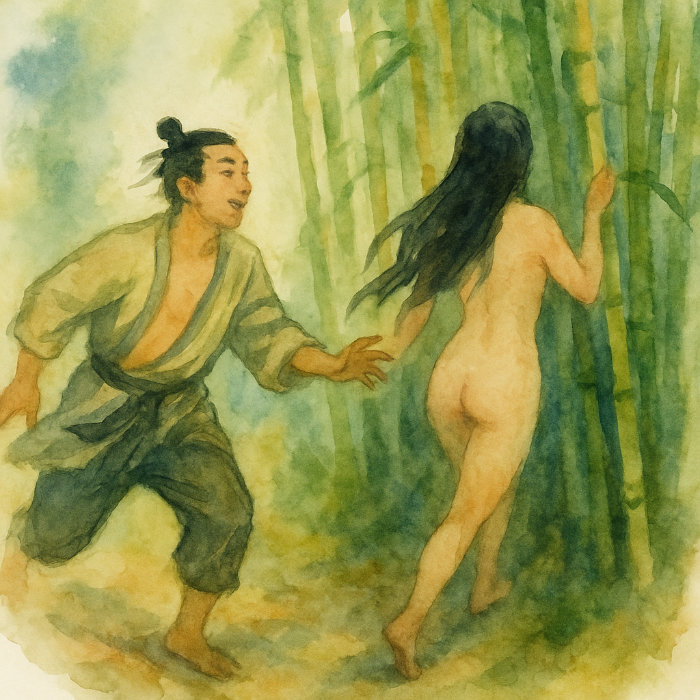

A sentry reported to Pu-erh that Bright Yang was last observed with one of the lower-ranking concubines, following a narrow path into a bamboo grove, half-clothed and crying out in abandon, in full pursuit of the elephant and grenadiers. She raised an eyebrow expressing initial surprise at the news, then appeared to be none too bothered. Mow Fung, however, observant of such minutiae as only an infant is capable, noticed that, still relatively expressionless, she was now infected with an occasional little sigh, which she would immediately stifle before anyone else but him could notice. He was quite entertaining, she thought.

The exaggerated local publicity surrounding the English marvels spread widely among the populace along the way, causing no end of anxiety for both Macartney and Dinwiddie, in fear that their exhibition might fail to meet the Emperor’s expectations. Macartney could do nothing but fret as the journey continued north. Dinwiddie, at least, could busy himself in preparation for the exhibition and his historic balloon flight.

During his weeks of preparation and waiting in the Forbidden City, he developed an infatuation with the refined, demure, though persistently aloof Sun Pu-erh. She seemed to observe everything through her inscrutable dark eyes, while her long, strategic locks, neither concealing nor clearly inviting access to his imagined fortress of her womanhood, were enough to elicit certain untoward thoughts in his own inflamed mind. He found himself drawn helplessly to the mysterious, dark, exotic femininity he’d read about in travellers’ tales and believed expressed itself in her every word and gesture.

He took her aside into the corner of a storage room to confess his feelings.

“D’ye mind I stroke your bonnie raven hair, lassie?”

She glanced over his large hairy nose, irregular ears, bushy eyebrows, and red whiskers – none of which appealed to her in the slightest – and gave a wry smile. To his mind, it was an encouraging one, so he gave her a wink and proceeded with his whimsy.

“Looks like silk, but feels a wee bit like the mane o’ a horse,” he confided.

In an effort to further his suit, such as it was, he professed a warm affection for her young son Chung, our very own Mow Fung of that era, a child blessed with a nature to be seen and not heard, one who would sit and watch him assemble his complex and precious marvels, without ever touching a thing.

“E’s a fine wee bairn,” he said. “I daresay I got three o’ ma own, and not one o’ em surpasses him in manners, nort be a long short.

“Now, the absence of the Emperor, along with almost the entire British delegation, gives us a rare chance to put my aerostatic globe through its paces and to mount a rehearsal that will allow everyone concerned to practise their roles. I’ll hold off, for the moment, from testing the discharge of fireworks from the craft, but will reserve that for the great day itself. We’ll hae nae beasts flung frae the heavens, nor French contraptions named “parachute.” Yon Blanchard – the great pretender tae philosophy, carnival-showman – may cast his ducks at Providence as he pleases! Rather, we shall save such spectacles for the day itself, to maximise the impression upon the Celestial Court that the potentialities – at once military and philosophical – of floating skyward in a silk-lined basket constitute nothing less than the definitive mark of a truly enlightened society.”

Pu-erh was invested with the imperial power to authorise such a project, and so it was done. The day approached for Dinwiddie to test-fly his globe.

“I will require a few of my assistants to set up the apparatus,” he said. “Is there a secure location? Best to maintain the highest level of discretion in order to preserve the element of surprise for His Nibs – ahem, His Celestial Majesty the something-or-other Emperor – ahem – when I reveal the aerostatic globe before him in all its magnificent sublimity.”

“Sire,” said Pu-erh. “I know a perfect place for your preliminary ascent. It is located in the north-west corner of the Imperial Garden of the Forbidden City, close to a Taoist shrine that is under my own humble administration. High walls, a few trees and structures, some open space.”

“Sounds ideal, my cherub. There we shall discover what shall transpire, according to the scientific method. P’raps a hydrogen one would’ha been better, but a difficulty – not insurmountable, mind ye – to manufacture the hydrogen right here. For all purposes, this beauty should amply suffice.”

The day before the planned launch, Dinwiddie’s team transported the apparatus from a storage room to the secluded north-west corner of the Imperial Garden. Our young Mow Fung stood apart from the proceedings, contemplating them beside Pu-erh, who observed silently, committing each step to memory in minute detail.

The envelope was suspended between two masts and tethered by six ropes, each gripped by a man. Dinwiddie ignited a pyre that had been placed beneath it, contained within a structure designed to focus the rising hot air into the mouth of the envelope, which expanded, revealing bright patches of red, blue, white, black, and gold. When fully inflated, the glory of the sphere, suspended in the air by its own force, was manifest: the English coat of arms, with a shield of the Empire and crown of the Monarch supported by a fierce lion and a noble, tethered unicorn. Beneath the arms, the motto Dieu et mon droit shone out in gold, proclaiming the divine majesty of King George III.

The envelope was detached from the masts and jockeyed into position beside the northernmost gate – the Gate of Divine Might – where the wicker basket stood in readiness. The two were lashed together with ropes, the silk slackening and filling by turns in the uncertain air.

The basket carried a burner to maintain the heat in the canopy above, with a supply of charred wool for fuel.

Dinwiddie cleared his throat and hushed his assistants for a spot of oratory. Adjusting his wig with the gravity of a sermon, he murmured, half to the heavens, “If Providence has pit China in the traupic, it’s no but that Britain micht instruct her frae the firmament.”

The balloon wheezed politely in assent.

At a shrill blast of Dinwiddie’s whistle, Pu-erh stepped forward as planned and was helped into the wicker-basket.

“Come along, laddie, dinna dawdle,” said Dinwiddie, lifting the boy in beside his mother, before climbing in himself. “Just a gentle ascent – straight up a wee ways, stay for a few minutes, and straight back doon. Cast off, lads!” he cried.

The craft began to descend immediately the ropes were loosed, so Dinwiddie struck a spark and stoked the wool-burner. In response, the globe bobbed to a halt.

“Too muckle ballast!” he cried. “Out wi’ ye, laddie!”

He took Mow Fung bodily and cast him over the edge into a pair of arms that happened to be there. The craft crawled upwards, reaching a height of about six feet – and there it stayed, hovering, obstinately refusing to rise any further.

“Ye be-luddy deevil o’ a thang!” he roared. “Off wi’ more ballast! Quick, gi’ out, gi’ out, gi’ off!”

Fixing him with a cool, level look, Pu-erh climbed out of the basket and took hold of a stay rope, guiding herself roughly to the ground. The craft began to ascend, slowly, and all on the ground dropped their ropes.

“Na! Dinna do that! Dinna do that!” Dinwiddie called down, but it was too late.

The balloon rose quickly to a point above the thirty-foot wall and was caught in a stiffening breeze. It took on momentum and, without any stays, sailed over the top of the wall, just beside the Gate of Divine Might.

As the wind took hold, Dinwiddie realised there was nothing to do but go over the edge himself. He slid down to near the end of a rope, but found himself still too far from the ground to let go.

Fortunately, as the craft drifted across the broad moat of the Forbidden City, the wind died down just enough for the balloon to descend, dragging his body through the water and giving him a chance to escape into the mud of the opposite bank.

The balloon gained height again and took off on an unmanned flight for several miles above Peking. The envelope caught fire from the furnace, and many perceived it as a dragon descending from heaven, to wreak havoc on the Manchu Qings.

Among the populace, alarm spread at the sight of the unicorn, glistening in the evening light – so closely resembling a legendary beast of their own, whose arrival had been anticipated for centuries. Archers fired upon the apparition as it bobbed and limped across the sky, striking sacred spots upon its body.

Snatches of an ancient song arose amid the cries of terrified onlookers, first muttered, then taken up by others:

The unicorn’s hooves!

The duke’s sons assemble,

Woe for the unicorn!

The unicorn’s forehead!

The duke’s cousins gather,

Woe for the unicorn!

The unicorn’s horn!

The duke’s kinsfolk arrive,

Woe for the unicorn!

When the craft crashed flaming into a field on the outskirts of Peking, it was set upon by peasants wielding spades, shovels, picks, and knives. No one was harmed in the incident, except that during the incineration of the balloon’s remains, all the hair on the head of one of its attackers was entirely burned off.

Dinwiddie was conveyed back to his quarters, where Pu-erh and her son were waiting. He waved them aside and, devastated and speechless, took to his couch for days, avoiding them both for the remainder of his stay in Peking.

Mow Fung noticed that from this time on, his mother tacked a tiny new gesture to the end of her occasional, apparently unprovoked sigh: a barely perceptible shake of the head. She would now say just one word to herself:

“Men.”

Addendum. Filed: Gate of Divine Might, 1793:

The foregoing episode is absent from the official papers of the Embassy, and from all Celestial memorials of the same year. No explanation is recorded, nor could one be; the event appears to have been extinguished at the instant of its occurrence. A trace persists only in a marginal entry among provincial gazetteers, describing the sudden descent of a flaming lion beyond the northern wall of Peking: a visitation later interpreted as the passing shadow of an immortal qilin (the “unicorn” of the translated song).

The entry adds that similar portents were recorded in antiquity, when a qilin was said to have announced the birth of Confucius, the Sage of Lu, and another to have appeared before Emperor Wen of Han. In Han and later commentaries, the song “The Hooves of the Unicorn,” long preserved in classical commentaries, was linked to the death of Confucius himself, for it was said that the capture and wounding of a qilin in Lu marked the end of his era. By analogy, the chronicler proposed that this fiery apparition might signify the renewal of imperial virtue, or else its exhaustion. Whether this was mass illusion, actual omen, or mere transcription error cannot now be determined.

© Michael Guest 2025

Leave a comment