Jade Volume

There is a mountain in the northern reaches of central China, known by devotees as Time’s Heavenly Sanctuary an Infinity above the Jagged Rocks. To the uninitiated, the summit lies at a distance no greater than a rice husk from the utterly impossible. And yet the region dazzles with natural vistas and unimaginable beauty. Many have tried to get to the higher elevations, but most failed. This is the realm not of mankind, but of the eagle, the heavenly tiger, and also the mischievous monkey who toys with the mind.

Below, a wide, pure, meandering river traverses a pristine landscape that extends into unknown territory, amid countless acres of giant bamboo, their upper branches seeming to beckon the breeze. The skies above are the sapphire blue of heaven. Hearts lift at the sight, and there are climbers so intoxicated by the vision that they hurl themselves in ecstasy to their doom – clearing the sheer cliffs and smashing against the rough boulders below. It is no wonder that, to a remaining few, Time’s Heavenly Sanctuary an Infinity above the Jagged Rocks is believed the holiest of holy places and, indeed, not to be slighted without profound risk.

The path winds upward through groves of giant bamboo, past shadowed outcrops and long-forgotten steps. Midway up the mountain’s flank, obscured by foliage and time, stand the ruins of a small, ancient temple – crumbling, barely visible through a thick curtain of green. Though seemingly deserted, the sacred fonts are kept full, and the stone steps swept clean.

Inside, a modest offering of a simple rice-ball and bamboo shoot invariably awaits the intrepid visitor. To come so far demonstrates a purity of heart that is well rewarded. To accept the offering in proper humility opens the senses to the contrast between the essences of darkness and light – a rare clarity amid the world’s illusions. But should the offering be taken improperly, or worse, scorned in any infinitesimal degree … then the shattered remains of the fallen, far below the cliffs, bear silent witness to the error.

Slightly below the temple’s ledge, until a century or two ago, burial tunnels were dug into the side of the sheer cliffs, extraordinarily deep, hand-carved tunnels in which it was the tradition to inter beings deemed noble of mind and spirit. It is said that, for the adept, the tunnels lead into a subterranean network that joins together all the holiest mountains in China, though not in the form of a physical labyrinth. Rather, access can be had only by an astral body, guided by the lines of an ancient map inscribed by the Tao on the shell of a certain large tortoise. Gravediggers would once upon a time swing down on ropes and steer one’s coffin into place in the cliff. Unsurprisingly, some of these erstwhile aerial ferrymen perished alongside their cargo, a worthy sacrifice for which they accrued what some call good Karma.

And still the mountain ascends.

Above this middle sanctuary of shrine and tomb, the mountain veils its final secrets. The temple, perched on a precarious ledge far above the valley, is not the summit. Beyond it, higher still and hidden from even the boldest climbers, lie the archives. Cascades of shining white water shield the opening to the cave, mighty enough to wash intruders away like ants. To human eyes, from all but an angular perspective of higher insight, the entrance appears no greater than a long, narrow crack in impenetrable stone.

Seldom indeed will visitors appear at these elevations – whether temple, tomb, or the archive beyond – in a living, physical form – but when they do, they find awaiting them the welcoming rice-ball and fresh bamboo shoot. Quite the mystery. Either there are ways to attain such heights known only to the peasants who reside in hovels dotting the mountain here and there, shrouded in mist, or else a supernatural force is at work. We adhere to the former explanation because, no matter how sheer the cliffs or tangled the paths on the way to enlightenment, there are always those who will dare to ascend and untangle them, even among us simple monks and peasants.

Yet there are also tales of hazardous spiritual journeys undertaken in order to consult the archive, in which an adventurer-adept awakens from trance to find the rice-ball and bamboo shoot in his mouth – rotten and crawling with maggots. And this although no flies exist above the treeline! The scenario is horrific, and it invariably concludes on the boulders at the foot of the cliffs.

The archive is a forest of books dating back to the earliest ‘butterfly’ volumes, constructed from vertical strips of bamboo, each inscribed with a line of text, and linked together into concertina-folded pages. The works kept in the archive are expertly arranged, meticulously ordered and colour-coded, their calligraphy flawless, their ink illustrations brilliant in economy. Naturally, they are dusty and draped in thick wreaths of spider web, for they are seldom taken up in the hand of a reader.

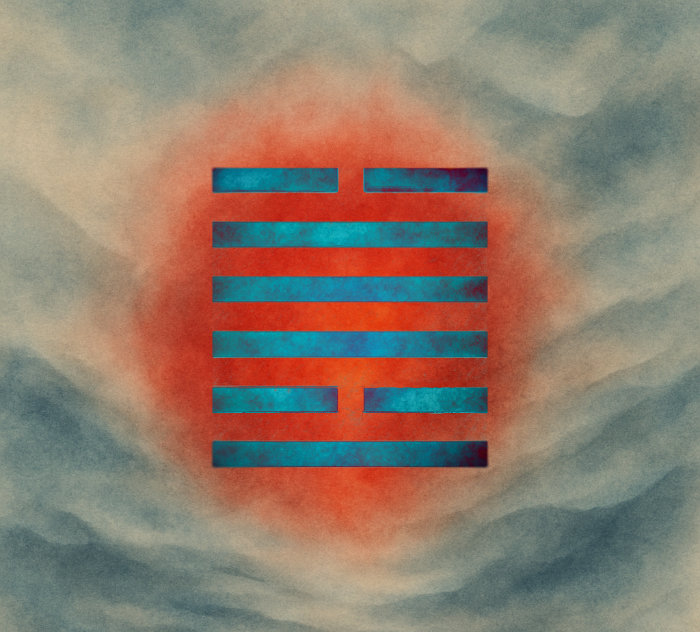

In the present day, the name of Chung Mow Fung yields only a single footnote, in a ‘recent’ volume from two or three centuries ago, referencing parentage under a different name. This name, however, is barred from formal publication, for it was altered by edict of the Tao, as made clear and manifest in the Forty-Ninth Hexagram: Revolution (革 – Gé). As Fire meets Metal (the lake), producing illumination, so too are personal desires refined into unselfishness. What is obsolete is shed like a snake’s skin; acquired pollution is burned away, revealing the essence of primal, unified awareness. The spirit aligns with its path. The great person changes like a tiger.

It was not uncommon for those of the Mow Fung line to alter their names – a necessary measure during those periods when the study of the Tao fell into disfavour with ascendant militant ideologies. When he settled on the southern continent, Chung had been his family name; however, local officials, in their ignorance, reversed the order. That moment marks the point at which we locate our pivotal index for extracting the lineage, and so the name becomes, in the final analysis, arbitrary. Yet the Mandarin denotation, Admirer of the Phoenix, perhaps remains apt. After all, how may we pin down a karmic ripple or trace an Akashic echo by means of a single name? Naturally, such terms are merely Buddhist and Hindu approximations, and useful metaphors at best, for, as Lao Tzu correctly observes, the true Way is named only tentatively: Tao.

So much for names. The Tao does not trouble itself with the consistency of library catalogues.

Although the familial lines extend back centuries into various narratives concerning the most enlightened individuals, this and further changes in name make certain crucial connections obscure, such that the specific ancestry becomes a matter of interpretation and even, in the worst cases, divination. It is like pursuing the strands of a fog. Any identifiable and named individual will not necessarily correlate with the line of the Mow Fung who occupies our current interest.

Some traditions suggest that Mow Fung is not so much a reincarnation as a resonance – a particular pattern in the Tao reasserting itself under a familiar-seeming name: a node through which the Tao’s intent briefly shimmers. That such a resonance might walk, speak, or even misbehave is not so much a mystery as a habit of the Way.

Perhaps he never attained enlightenment, nor will his descendants, his temperament being of a too weak, too dark, too yin-flavoured humour and given to excesses of the flesh: notably, unmindful congress and the ingestion of hallucinogens. Unfortunately, even such faults are not as uncommon as the reader might like to think, even among the membership of our venerable community of ancestors, among whom number not only sages and adepts, but also a handful of artists and poets whose conviction in their own genius outpaced any objective manifestation.

It is gathered from the relevant volume that this ‘earlier’ Mow Fung was the son of an accomplished civil servant who, after becoming a father, subsequently became a eunuch in the imperial court of the Qianlong Emperor, where he enjoyed a cheerfully untroubled life. Nicknamed, with some irony, Ma Tan-yang, or “Bright Yang” he achieved a degree of enlightenment, thanks to the tutelage of his wife. She, Sun Pu-erh (“One Hearted”), was a child prodigy and a brilliant scholar and seer, trained in a clandestine temple of the Taoist School of Complete Reality (now officially suppressed, but only on paper) and endowed with unsurpassed expertise in the study of Confucius.

Moreover, she was a brilliant exponent of foreign languages, which she studied under the tutelage of a Jesuit missionary and painter named Giuseppe Castiglione. She was an adept of high degree, directly descended from the female Wu, the most powerful sorcerers of all time, and engaged as a high adviser in the imperial court. Her husband was charged with supervision of the Emperor’s concubines, who instructed him in the most up-to-date nuances in fashion and cosmetics, in exchange for tutoring them in all sorts of corporeal practices in which he was expert (see Indigo Volume XXXXIV of Late Tang Dynasty Collection, and Emerald Volume XXVII of Song Dynasty Collection).

•

One day the Emperor summoned Sun Pu-erh and her foolish young husband Bright Yang to the Hall of Supreme Harmony, in the Forbidden City. Sitting on his Dragon Throne, which marked the centre of the universe, he assigned them a mission. Backed by a magnificent screen of gold, he appeared a multi-coloured, superhuman gem. His voice echoed around and among the six huge gilded columns immediately before him, each encoiled by his own five-clawed dragon. Touch one if you wish to die. The ruler of a round-eyed, red-haired, ghostly-skinned barbarian rabble from a far-flung isle had requested that he receive a delegation. The chieftain, who called himself King George III of England, a territory he described in terms so overblown as to border on hilarious arrogance, wished to discover the wonders of the Great Qing, for the betterment of his own ‘civilization’, which the Emperor understood to be the lowliest among all those in Europe.

“His baser wish is that we grant certain concessions to his barbarian merchants. Hitherto, all European nations, including those of his own realm, have carried on their trade with our Celestial Empire, as permitted solely at the port of Canton, a restriction he now seeks to overturn.

“What is the meaning of this word ‘king,’ anyway?” the Emperor said, looking at Pu-erh, who had memorized all 11,099 volumes of the encyclopedia housed in the Hall of Literary Glory.

She bowed her head and replied.

“Perhaps related to another word they use, ‘kin,’ implying he is the father of their extended family,” she said. “They say also that ‘the lion is king of beasts,’ referring to their imperial symbolism. Evidently there are no lions there, are there? Perhaps they seek to differentiate themselves from Caesar, derived elsewhere as Czar or Kaiser. I imagine it all originates in Roman times ”

“Cease!” the Emperor said curtly, and continued:

“His letter is illiterate. You see, here he addresses us as ‘the Supreme Emperor of China … worthy to live tens of thousands and tens of thousands thousand years.” He coughed lightly, tittered, and cast a glance at the ceiling – augustly decorated with framed images in jade, ruby, and gold leaf: dragons, qilin, phoenixes, and other fabulous beings from the four corners of the earth and beyond – while an imitative titter rippled among the courtiers.

“However, despite his clumsy expression, we take note his respectful spirit of submission,” he said, raising his hand to cut short the disturbance. “We determine that he is sincere in his intentions.

“It behooves us here at the centre and apogee of the world to cast our light before such peoples, backward peoples, but those who have nevertheless drawn themselves up to attain a state in which they manage to discern the magnanimity with which we bend towards them and allow them to participate in our beneficence, and therefore shall we acquiesce to these requests. Never mind how meagre their offering, we shall treat them with generosity and luminosity. After all, it is our Throne’s principle to treat strangers from afar with indulgence and exercise a pacifying control over barbarian tribes, the world over. Make a special note,” he ordered his scribes, who were taking down his words.

“His delegation of a hundred men will arrive in China at any moment now, concluding a year’s voyage from the far-flung regions of barbarians, by way of several countries even more primitive than their own, in the Americas and in Asia. Naturally, we are already well informed about all parts of Asia, thanks to our numerous voyages of discovery and trade, so we require no enlightenment from this English impertinence. Ha! In the year 1405,” he said, his voice rising, “during the Ming dynasty, Admiral Zheng He discovered America – seventy-five years before the Spaniards. And during his seven expeditions, he mapped the entire globe: the Mediterranean, Africa, the Americas, and even Australia.” He looked again at Sun Pu-erh, who bowed her head.

“I have seen it in an archive in the Pavilion of Literary Profundity,” she said.

“We have had little need since those times for forays abroad. Our Celestial Empire possesses all things in prolific abundance and lacks no product within its own borders. Make a special note, underlined,” he commanded the scribes.

“Since the barbarians have developed some abilities in seamanship, they now scramble to us,” he continued. “We remain loath to admit them – all the more, given the skirmish playing out somewhere over there in those parts, some minor uprising …” He looked at Pu-erh, who bowed her head.

“The French Revolution,” she said. “King Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette beheaded, and so on.”

“Correct, what they call the French Revolution. Well, we don’t want that sort of nuisance over here, do we?” He looked at Pu-erh, who lowered her gaze and said nothing.

“At any rate, the weather has become unseasonably warm in the capital, and we have decided to repair to our summer palace and mountain resort in Jehol. You two will meet the ambassador, one Lord George Macartney, en route to Peking, and advise him of our change in plans. His entourage will rest for three days before proceeding north for an audience with us. Pay close attention to any equipment or paraphernalia he must leave behind during his sojourn. He intends to amaze us with certain marvels of English invention. Though we anticipate little worthy of attention, we wish to see recorded, in fine detail, the technical principles of any scientific apparatus – particularly weapons or devices of use in the art of war – that they intend to demonstrate.

•

The couple travelled by palanquin with a modest retinue. They found the envoy, news of whose approach had long preceded it, at the town of Tongzhou, a canal terminus.

The thirty-seven imperial junks that had carried it thus far along the shallow White River could go no further, although the military escort would continue. Armed with bows, swords, and rusty-looking matchlocks, the troops marched in single file, beneath standards made of green silk with red borders and enriched with golden characters. Long braids, tied at the end with a ribbon, hung down their backs from beneath their shallow straw hats.

A wonderful rigmarole attended the transfer of Lord Macartney’s cargo to a convoy of carts, wooden wheelbarrows, and coolies – those labourers pressed into toil for wages scarcely worthy of the name – for the next leg of the trip to Peking. The spectacle inspired in many of them the words from ancient songs, to which they lent their voices while they toiled:

Do not work on the great chariot –You will only get dust in your mouth.

I sing of those who are far away,

And sorrow clings like a cloak.

The great chariot groans with its load –

And saps the strength from my bones.

I think of those who are gone,

and my heart is cut open again.

The great chariot creaks at the axle –

It cannot bear the weight.

I remember those who fell blinded by the dust,

On the side of this distant road.

Some of the labourers were given a taste of the whip by their military guards, who perceived seditious intent in the stanzas.

Thus concludes the scroll of the Jade Volume. The continuation has – most vexingly – been mislaid in a dark corner by one of those accursed archival monkeys, necessitating a brief but unavoidable interruption in our unfolding.

Images generated by AI

Leave a comment