Once the blackened remains of his aerostatic globe were retrieved, Dinwiddie took to his bunk, afflicted with a profound dread usually reserved for the condemned. He shook, perspired, quivered, and palpitated; so much so that Pu-erh, apprehensive of her own fate, having been placed in charge of the Scot by the Qianlong Emperor himself, summoned a team of imperial physicians and acupuncturists. Their examination of his tongue revealed flaws in the state of his kidneys, bladder, intestines, stomach, spleen, lungs, heart, gall bladder, and liver. Moreover, its shape and colour pointed to a severe deficiency in Qi; red dots suggested heat or inflammation in his blood; and the thick coating was indicative of an allergic disorder compounded by digestive imbalance. He was dosed, moxibusted with mugwort, and cupped, scraped, tickled and pricked to the point of tears and bellows.

He may as well have reclined sunning himself in the Imperial Garden, for Lord Macartney’s overtures to the Emperor had crashed and burned as completely as the globe, with tangible repercussions for the delegation. Macartney, preoccupied with weightier matters, had never much cared for Dinwiddie’s pet project in any case, and failed to notice its absence from the exhibition.

Dinwiddie resurrected himself and managed to prepare for the official event. The Emperor was contemptuous, tarrying for less than five minutes before repairing to the quarters of his latest concubine. After his disdainful exit, Pu-erh conveyed his comments to the scowling Lord Macartney and deflated Dinwiddie:

“Your air pump is of little interest, though the telescope might amuse children. He finds your planetarium infantile too – not unlike the sing-song clocks hawked in the Canton marketplaces,” she said. “The Emperor already owns a superior model, anyway, presented as a personal gift by a German delegation. It is true your giant lens can melt a copper coin, but will it melt his enemy’s city? He believes not.”

The next day, she was summoned to the Dragon Throne. She kowtowed three times as she approached. The imperial ministers, secretaries, and scribes were in attendance, assisting the Emperor draft a reply to King George’s letter. Her attendants delivered the sketches and notes she and her agents had compiled regarding the scientific instruments.

“You have performed your duties exemplarily, our flower,” the Emperor said. “Our indulgence of the foreign delegation, exasperating though it was, has nonetheless proved edifying in certain significant respects. Their ships are capable and well-armoured, their weapons powerful beyond our anticipation. It is useful to glean these odds and ends regarding the abilities of their scientists and craftsmen. Oh, that fellow, that worm …”

“Lord Macartney,” prompted an advisor at his side.

“That’s it – Macartney. I will never forget that spotted mulberry suit of his – the enormous diamond star, medals festooning his chest, and that hat – that ridiculous plume of feathers! The very image of presumption and self-importance. What a … peacock! But bumbling as a poacher setting snares in the Imperial Garden!” He let out a hearty laugh, provoking a ripple of hilarity among the ministers.

“Insufferable dunce and fop. Humming and hawing about the significance of rituals and this and that, how he should bow and the rest of it. Disdains kowtowing to our Throne indeed, but performed some silly sort of jig instead. And they wouldn’t leave! They would like to have remained in Jehol the whole summer long! Those English have incurred my great displeasure – no more favours for them. Mark that, a ministerial edict for you: No more favours. Allow them two days to gather their paraphernalia, then escort them from the capital forthwith. The nonsense of this king, his wild ideas and hopes. Ah, that is apt! make a note. Come, take this down,” he said, flicking his fingers at the nearest scribe. “We shall draft the edict:

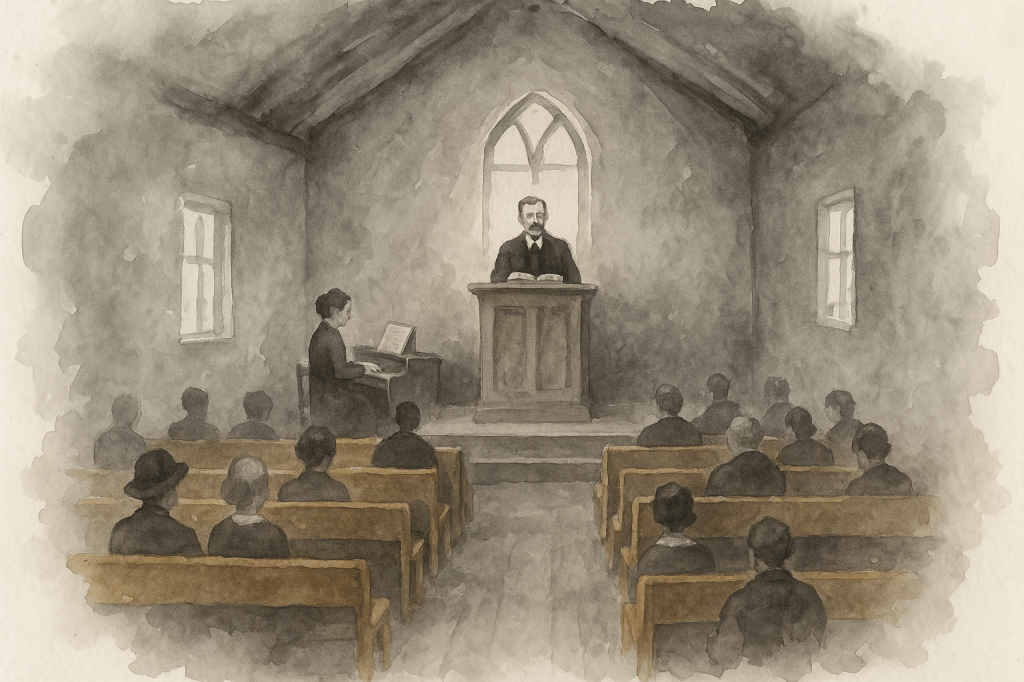

“Your England is not the only nation trading at Canton. If other nations, following your bad example, wrongfully importune my ear with further impossible requests, how will it be possible for me to treat them with easy indulgence? Yes, good, and while I think of it, that point about letting in their proselytizers … Regarding your nation’s worship of the Lord of Heaven … Ever since the beginning of history, sage Emperors and wise rulers have bestowed on China a moral system and inculcated the code of Confucius, which from time immemorial has been religiously observed by the myriads of my subjects. There has been no hankering after heterodox doctrines.

“Well and good,” he said, looking down at Pu-erh and granting her a broad, warm smile. It was the first smile of any sort, indeed, that she had ever received from him. “Foreign ideas and fancies can breed serious disharmony, can they not, our petal? The last thing we need is exposure to them. What was it that my father used to say? ‘Destroy the seed of evil, or it will grow into your ruin,’ or something to that effect. By the way, how is your beloved Bright Yang? Has he returned with the tiny elephant and soldiers?”

She averted her eyes and slowly shook her head.

“You see, I know more than I let on,” he said. “I even heard scraps of a crazy rumour that the barbarians can fly! The nonsense that gets around. Never mind, he was unworthy of you, that Bright Yang. Yet fear not, a woman as intelligent as yourself must be much sought after. Is such a brilliant flower, however plain, worth more than the prettiest concubine? No, she is worth ten of them, and not just for lacking their vacant minds. Stupidity makes a concubine restful. But you, dear petal, you keep us guessing. Oh, that is not quite well put, is it? Naturally a pretty concubine is all the better when graced with an astute mind, is she not? How old are you, our petal? When were you born?”

She told him, and he slowly shook his head.

“That is what I have heard tell, but would you truly have me believe in the gold elixir of immortality? Have no qualms, our enlightened one, you need not seduce me with the fairy tales of your sect. Despite my patronage of Tibetan Buddhism and my abiding friendship with the Dalai Lama, I do not entertain the slightest aversion to your affections for the Tao, though its religion and philosophy I neither believe nor understand. Alas, there are far too few of you left in the upper echelons, though I’m told that some of your rural cults are regaining popularity amongst the poorer, lower-class folk. No matter, you have earned our fond indulgence, and may rely upon it to the end of your span under Heaven.”

Again he shed the glow of his smile upon her, or so it seemed, enhaloed as it was in the golden rays reflected from the Dragon Throne.

If Pu-erh had never doubted the Emperor’s enduring patronage, she did now. Another warm smile deepened her unease. He dismissed her and returned to work on his epistle to the British.

“The beginning and middle are good,” he said, “but the end needs attention. Where were we? Ah yes … I do not forget the lonely remoteness of your island, cut off from the world by intervening wastes of sea, nor do I overlook your excusable ignorance of the usages of our Celestial Empire. I have consequently commanded my Ministers to enlighten your Ambassador on the subject, and have ordered the departure of the mission. Etcetera, etcetera, etcetera … Now for a firm conclusion: Should your vessels touch the shore, your merchants will assuredly never be permitted to land or to reside there, but will be subject to instant expulsion. In that event your barbarian merchants will have had a long journey for nothing. Do not say that you were not warned in due time! Tremblingly obey and show no negligence! Yes, that should do it! Inscribe this missive on yellow silk of the finest quality, deliver it to the mulberry peacock and impose my edict upon him to begone in two days’ time, at the risk of your heads!” He uttered the final phrase in an ominous tone that echoed in the hall, then smiled broadly.

Lord Macartney received the yellow silk epistle, mercifully unreadable to him, and departed China ignominiously, his retinue and exhibition articles hastily boxed. Aboard the Lion as she set sail from Macao, he stood on deck with her captain.

“Are they ignorant that a couple of our English frigates would outmatch his entire antiquated fleet?” Macartney said bitterly.

“From what I have seen,” the captain said, “it would take no more than half a summer. Half a dozen broadsides would block the so-called Tiger’s Mouth, which guards the waterway into Canton.”

“The population would be condemned to starvation. The Empire of China is much overrated. He is a crazy old man of war, kept barely afloat these past hundred and fifty years, which through its impression of bulk has managed to overawe its neighbours. Ah, he’s rotten at the timbers …”

“Through and through, m’lud. It won’t be long. He’ll drift as a wreck and surely be dashed asunder on the rocky shore.”

“The tyranny of a handful of Manchu tartars over three hundred millions of Chinese, who will not endure their condition for much longer. Still, we must forbear while a ray of hope remains for the success of gentle measures. At any rate, left to its own devices, I believe the dissolution of this imperial yoke will precede my own.”

The captain watched the lord’s back as he paced away, then turned discreetly from the breeze, to shake his head, light his pipe, and allow himself a wry face at the tales of his superior’s disastrous mission, which were attaining satirical proportions amongst members of the envoy and crew.

• • •

Approaching twilight, two unexceptional sojourners tramped down the dusty track that skirted the flank of Timeless Mount – a poised woman and a mustachioed youth – both clad in plain, weather-worn robes, the modest dress of those who have forsaken rank. Though travel-marked, they bore the composed, abstracted air of those returned from beyond time’s keeping.

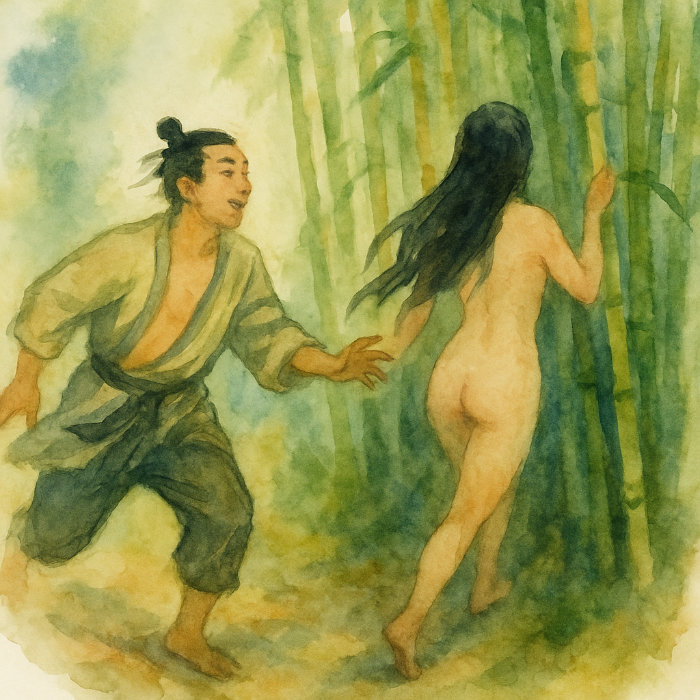

As they neared a fork in the path, one arm climbing higher, the other tracing a ridge eastward before dipping into dense forest, three grizzled bandits in big boots and hats came up behind them.

“Oi! What’s your hurry, peasants?” one of the bandits growled and the two turned to face them, bowing low and repeatedly, out of old acquaintance with peril.

The one who had spoken snorted his satisfaction at what he perceived as their humility, blind as he was to the absence of fear in it. “You can chuck down all that stuff,” he said, jerking a thumb, the other hand gripping the hilt of his goose-wing sabre, as he limped toward them. The pilgrims eased their carry-poles from their shoulders to the ground. “Toady, have a look-see what we got ’ere.”

One of his henchmen, distinguished by the angry boils covering one side of his face, did immediately as ordered, dropping to his knees before the packages and opening them up. Periodically, he scratched at his face, his boils themselves seeming to have boils.

“Clothes and stuff, pretty nice, silk even!” he said, holding up a deep blue scarf patterned with peonies. “Now, what have we got ’ere in this box? All this writing-stuff and little statues and books and bells and little pots, and all sorts of other useless rubbish.”

“What about food?” said the third bandit, urgently, his eyes wide.

“Hold on, Yongyan, give me a minute. We got some carrots, rice, and beans. Not much chop.”

“Better than nothing,” said the third bandit, a man more corpulent than hardened. “We got more back at camp, anyway.”

“Pack it all up, you two, and let’s be off.”

Down from the track they stumbled with their prisoners, pushing through the bamboo until they came to a small cleared area with a fire-pit and the rough wherewithal of a bandit’s trade: a meagre stack of weapons – spear, pike, sword, and a musket – and a dismal pile of loot, which they may as well have obtained by begging: a modest heap of bronze coins, a studded leather belt, an old bamboo flute, an abacus, a compass, a wooden figurine of the Buddha, a drawstring burlap pouch, and other odds and ends.

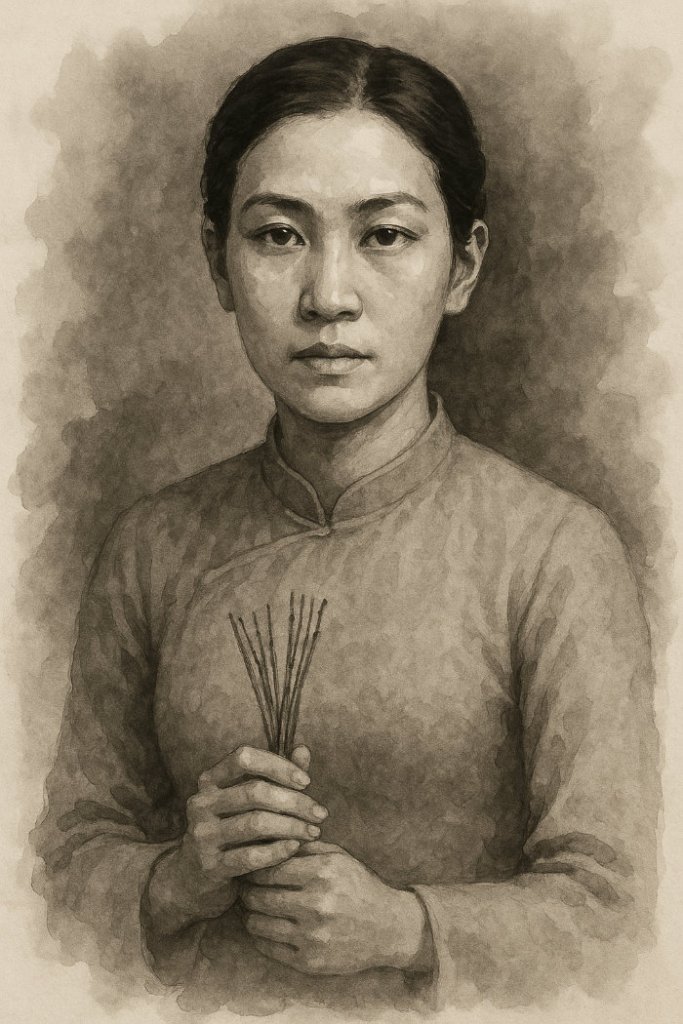

Pu-erh and her son sat in silence, loosely restrained by a rope, observing the men as they cooked up the food, ate, and passed around a flagon of rice-whisky. She was adorned with not one extra wrinkle since we last saw her, all that indeterminate period before, though her little boy Mow Fung was matured into an adolescent fellow of lean frame and quiet grace.

“Better give them a bit,” the leader said through a mouthful. “Might be the last meal they ever have before getting all sliced up into bits and pieces and their heads chopped off.” His guffaws dwindled when she fixed him in her level gaze.

“Your name, sir?” Pu-erh said politely to the one with boils, who leaned over to them with two wooden plates of beans. She and her son had already freed themselves from their restraints without any fuss. The bandit had removed his headwear, and even in the dim light one could see that the boils continued up from the side of his face and across half his cranium.

“He’s called Ugly Toad,” the leader said. “The other one goes by Yongyan the Hungry. And me? Wang the Eviscerator.” He lifted his sabre from the ground beside him and waved it in the air. “And this ’ere’s what does the evisceratin’. So you better watch your p’s and q’s, got it? Are you from around hereabouts? We’re new ourselves, lookin’ for a good place to set up a proper hideout and all that. Heard there’s treasure up on that next mountain, Time’s Heavenly Sanctuary Blah-Blah-Something-or-Other, so we figured we might head up there a ways.”

“That would seem an unfavourable location for those of your profession,” she said.

“Oh it would, would it?”

“Certainly, unless you would enter the lair to look for the tiger.”

“Allow me to be the best judge of that,” he said. “But go on, proceed, tell us a bit about it, since you seem to know so much about everything. What is it you do around this neck of the woods, scratch the dirt, I suppose?”

“Simple hermits. We study and improve ourselves; distill the gold elixir; wander from village to village; tend the hidden temple; heal boils; make rain; exorcise ghosts; give blessings; heal boils (it’s a recurring problem); prophesy destinies; interpret the countryside; create and burn talismans for good or ill fortune …”

“Ar, got it,” said the leader and guzzled from the flask. “Quacks. What a coincidence. You know, before this we worked as ginseng poachers in Fusong County up at Changbai Mountain. Not much fun, I can tell you. You get those Manchus after you, because it’s their sacred place, you see; and then you get the black bears too. If it’s the Manchu, you run like the wind, for your head’s at stake. If it’s the bear, you don’t run or fight, whatever you do, but play dead and freeze, and be good at it, too, because they’ll push and prod you around to see if you’re faking, and if you are, they’ll more than likely take your head off before they gobble you up. Here, I’ll show you one of my gut-wounds, still septic it is after all that time. Pretty nice, eh? Well, I never made a peep, you better believe it, though he licked all over my face and blew his rank breath up my nostrils. The ginseng takes a lot of poaching indeed – but if you know what you’re doin’ it’s worth more’n silver. Sometimes, if you’re lucky you’ll hear a special little birdie singing, what’s telling you the ginseng is there; and if it is, it’s so fiddly to get it out you might as well not even try. The root can disappear or run away, too, because it’s magic. It’s just the exact shape of a human and it’s got the mountain spirit in it, so you have to lasso it by the sprouts with red cotton thread with the ends weighed down with two bronze coins. Then you tie it up to a sort of special trap until you dig it out without breaking any of it, which is next to impossible anyways. We’ve saved two in that little sack, which is about all we got out of the exercise. To tell the truth, we haven’t been much chop at working as bandits, either, but that’s another story.”

“Gold elixir …” said Yongyan the Hungry. “Any alcohol in it?”

“In the modern day, it’s generally understood as a potion of immortality formed within,” Pu-erh said. “Hence the term inner alchemy. The gold elixir is the innate knowledge and power of the mind – a fusion of vitality, energy, and spirit: the forces of creativity, motion, and consciousness – refined through rigorous observance of the Tao. By contrast, external alchemy follows the example of one of the Eight Immortals, Iron-Crutch Li. Its goal is to concoct a pill of immortality by combining ingredients like lead, mercury, cinnabar, and sulphates, then firing them in a furnace. Unfortunately, the ingestion of such pills often results in death. Some lesser practitioners attempt to raise their consciousness through crude experiments with plant extracts.”

“Deviant practices,” Mow Fung said, with the shadow of a smile, closing his eyes. The bandits stared, then glanced at one another, slack-jawed.

“He don’t say too much, do he?” said Wang the Eviscerator at last.

“Those days are gone,” Pu-erh sighed, “when condemned prisoners were made available as subjects for such experiments. As for these mountains, they are favourable to our alchemical purpose: the pursuit of the elixir. For here, tucked in a valley that time forgot, lies a village where months pass as years and the people scarcely age.”

“Heal boils, do you say?” said Ugly Toad.

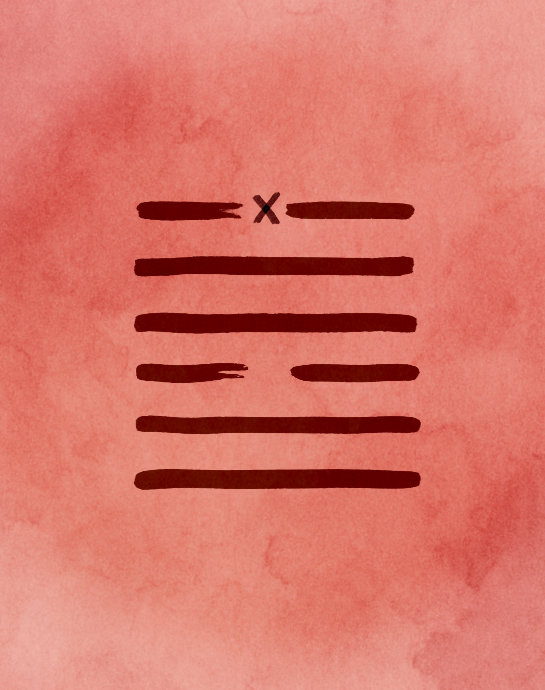

None of the bandits paid any attention as Mow Fung retrieved the bamboo flute and moved to the edge of the clearing without a word, where he sat down cross-legged again and began to play.

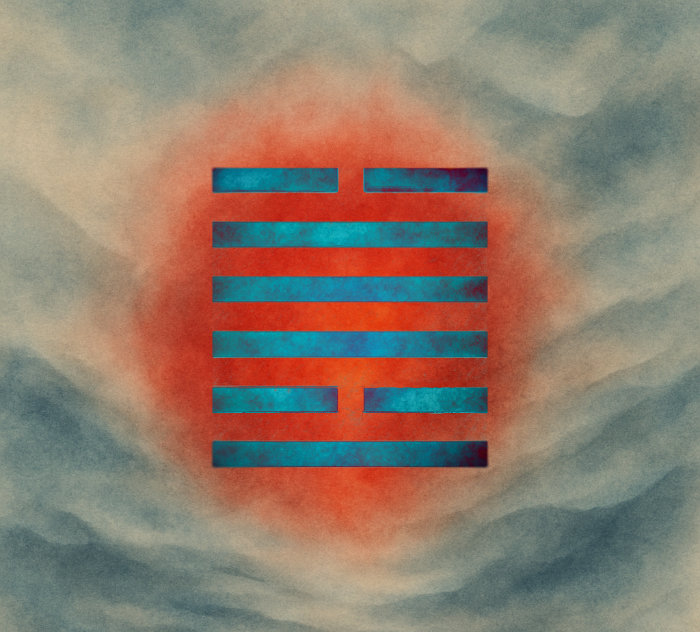

The campfire crackled. He ad-libbed lento through melodic variations once taught to him by the Imperial Music Master, as a favour to Pu-erh. In theory, they formed a transcendent framework based on the King Wen sequence of I Ching hexagrams from the late Shang Dynasty, embodying a microcosm of the universe.

Without effort, the young man lent the intrinsically dry exercise a style idiomatic to the flute, evoking in everyone present an impression of a lonely moon suspended in a frosty autumn night sky, though not one of them made mention of it.

As he played, he reflected on dim memories of his infancy in the Forbidden City, and on the blurry period that followed, living their lives in hiding and reclusion among caves and forests, and in the infinite seclusion of the mountain. How the years had flown since they fled, when one looked back, while seeming, minute to minute, to progress in ordinary time – so that he, an apparent “youth” – had lived the span of perhaps two lifetimes for one of his corporeal age.

“You might as well keep that thing,” Yongyan said. “None of us could get a note out of it.”

“What was that you were saying about boils a while earlier?” Ugly Toad asked quietly. “I’ve been having trouble with these for years. Getting worse rather than better, I’m afraid.”

“Those little blemishes?” Pu-erh said. “Why, you can hardly notice them. They’re really not worth bothering about too much, do you think?”

He gave her a meek and appreciative grin. “I’ve tried all sorts of remedies from quacks all over the countryside, but they’ve only made things worse.”

She took a dab of unguent from one of several minuscule clay pots stacked into her carry-sack and told him to apply it. Though scarcely more than a smear, it seemed to warm in his fingers and swell slightly as he rubbed it in – not diminishing, but softly renewing itself. After a long while, she told him to save what remained for daily use. There would always be enough, she said, so long as he didn’t try to measure it.

“Feels better already,” Ugly Toad said to Wang the Eviscerator. “You should try it, you know, for your belly.”

“Well, you do realize I was only kidding about cutting you up into bits…” Wang said to her through his toothless grin.

“I knew your capabilities the moment we met,” she said, “and I was doubtful they include the eviscerating of unarmed victims. Unfortunately, the unguent is only a salve, a stop-gap measure. Cures for both your complaints will require substantial time and involved procedures. Take heed that if you leave your bear-wound as it is to heal, you will assuredly die. Moreover, if you lead your party to seek treasure on the upper mount as you implied was your plan, the three of you will surely perish all the sooner.”

The following morning the five took the lower path, hiking along the ridge and descending into thick forest. They entered a narrow trail that soon forked into a dozen offshoots, each of which branched again and again into near-identical tracks, until they found themselves in a bewilderment of forks and false turnings. Only Pu-erh and Mow Fung seemed to know the way. At last, near midday, they emerged before a dilapidated temple, half-lost in the undergrowth.

“Rest now,” said Pu-erh. “We will return before nightfall.”

The temple and its crumbling attendant building sat on a ledge where the land dropped away into a mist-filled void. Behind it, cliffs fell sheer to silence, visited only by haughty eagles who wheeled and nested in the inaccessible crags.

The three bandits felt a rush of exhilaration at the sight – a sensation unlike any they had ever known. They settled in to await the return of their two guides or perhaps some wandering monk. An overwhelming solemnity fell over them, as though from this high place one might commune with the Eight Immortals – whoever they were.

“We were looking for a hideout, and we have found one,” said Wang.

“Without knowing the way, no one could ever get in,” said Toad.

The void was an immense auditorium of silence, from whose depths came the thin cry of a hawk.

“… or out, for that matter, you might say,” said Yongyan.

“You don’t think …”

The three cast glances at each other, before settling down for a smoke.

“How could you suggest such a thing?”