Picaresque novel cum Bildungsroman, Thomas Mann’s Confessions of Felix Krull, Confidence Man (1954; trans. Denver Lindley) resonates with the late modernist psyche. Mann’s novel prefigures a psychiatric epidemic of our day, psychopathic narcissism. In this widespread postmodern condition, the fragile identity implodes in its own process of self-aggrandizement, sucking in those closest around.

The Talented Mr. Ripley (dir. Anthony Minghella, 1999) is a recent cinematic iteration of the theme, via the 1955 novel of the same title, written by the American writer Patricia Highsmith. Mann’s novel is more subtle, turning away from any formulaic moralistic closure.

What underpins identity? Might one abnegate the self, and if so, what would be the implications? If a self were infinitely transmutable, who would be the self that exercised the will to make it so?

The power of narcissism. The fragility of the self. What underlies the self? Mann explores issues like these. Particularly fascinating is his approach to the implications for the act of reading his novel itself, which manipulates an array of masks that the author and reader assume implicitly.

Mann’s novel is a stylistic parody of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s autobiography — grand, pompous, aesthetic, philosophic. The technique lends the narrator-protagonist Felix a high-flung, unconsciously self-parodying viewpoint throughout his “confessions.”

Don’t mind that the novel was unfinished due to the author’s death (at 83 years of age, by heart failure). The story coheres by its own volition, climaxing spectacularly (actually, at a moment of sexual climax!) at a point whose aesthetic and moral effects are empowered throughout the narrative, toward that peak.

The final climax is the third of three memorable encounters throughout Felix’s sexual history to date. At age sixteen he enjoys secret trysts with his household maid Genovefa, in her early thirties. At twenty, when working as a lift-boy at the Hotel Saint James and Albany in Paris, he has an affair with a married woman, whose jewel case he had accidentally acquired en route by train to Paris, but keeps.

Our Plot

Narrator-Felix exhibits a divided attitude to the strictures of artifice, aware that a story-teller

… ought not to encumber the reader with incidents of which “nothing comes,” to put the matter bluntly, since they in no way advance what is called “the action.”

But perhaps it is in some measure permissible, in the description of one’s own life, to follow not the laws of art but the dictates of one’s heart.

Regardless, let’s briefly outline some of the salient points of the plot, while considering thematic implications here and there along the way.

1. The Rhine Valley

Felix Krull grew up not far west of the German city of Mainz. He was born “a few years after the glorious founding of the German Empire,” which dates the story as post-1871.

He believes himself to have been a “Sunday Child” (that is, full of grace), with splendid looks, charm, intelligence, talents and sensibilities, as he regularly reminds the reader, maintaining

the unshakeable belief that I am a favourite of the powers that be and actually composed of finer flesh and blood.

His bourgeois family enjoys an idyllic and decadent lifestyle, in which Felix provides some of the prime entertainment, with his dressing up and games of make-believe. His father is the brewer of an inferior brand of champagne, “Loreley extra cuvée,” which flows copiously during social gatherings full of “merriment and uproar.”

Felix’s parents organise these events often, because they “bore each other to distraction.”

Felix’s godfather Schimmelpreester is a formative figure in his early life, encouraging and applauding his antics. After the death of Krull senior by suicide — a consequence of the unsurprising collapse of the family wine business — Schimmelpreester arranges employment for Felix in Paris, which he will take up after a short stay in Frankfurt, where his mother is to operate a rooming house, christened the “Pension Loreley.”

2. The Hotel Saint James and Albany, Paris

“You seem,” he added, “either a fool or possibly a little too intelligent.”

“I hope,” I replied, “to prove quickly enough to my superiors that my intelligence functions within precisely the right limits.”

Mann’s high-flung, parodic style invests Felix, as narrator and character, with an enchanting quality of self-parody, even as he extols his own virtues, while inwardly mocking the imperfections of most if not everyone around him. As narrator, he seduces the “narratee” — the projected reader’s persona to whom he addresses his “confessions” — into complicity. If he omits certain details, it’s because

a reader of sensibility (and it is for such readers alone that I am setting down my confessions) will have realized it by himself.

Note how the term ”confessions” implies the truth of what Felix says. He dons a certain air of pristine naivety like a halo of innocence. But the “truth” is an inherently vacillating quality, as its affirmation by this compulsive confidence man attests. After all, to what extent will the reader be duped into Felix’s own confidence?

Does this motive underpin his periodic overtures to his reader (“if I ever have one”) — to his “discriminating,” “earnest,” “solicitous” and so on, readers?

Anyway, Felix is christened “Armand” by the hotel, the name of the previous elevator boy. He works for a while in the job, before attaining a position as waiter, having casually undermined an elderly employee who occupied it. He charms the hotel guests, to an extent that requires he evade advances from members of both sexes.

The owner of the misappropriated jewel case is one magnificently demented Madame Diane Houpflé from Strassburg, a dilettante novelist who writes “in the shelter of [her husband’s] riches.” She and Felix join in a torrid one-night stand:

She came. We came. I had given my best, had in my enjoyment made proper recompense (174)

which his admission about the jewel case serves to heighten:

“I have a wonderful idea.”

“What’s that?”

“Armand, you shall steal from me. Here under my very eyes. That is, I’ll shut my eyes and pretend to both of us that I am asleep. But secretly I’ll watch you steal. Get up, as you are, thievish god, and steal! […] You will find all sorts of things under the lingerie. There’s cash there, too. Prowl around my room on cat feet and catch the mice! You will do this favour for your Diane, won’t you?” (179)

Substantial profits from this encounter enable Felix to rent a small apartment in the city and dress himself to the nines. He dines and attends the theatre incognito, while continuing to work quite happily as an elevator boy, admiring himself in the livery.

On an outing to the rooftop garden of a luxury hotel, he bumps into Louis, the Marquis de Venosta, a dilettante artist about the same age as Felix, whom he has served (and charmed) at the hotel where he works. Venosta marvels at Felix’s double life and is astounded at the staggering qualities of talent and aplomb that enable him to bring it off.

3. The city of Lisbon, Portugal

The marquis is in a quandary. He is madly in love with the beautiful, vivacious Mademoiselle Zaza, a singer who performs scantily clad as a soubrette at a little theatre, Folies Musicales, (and with whom Felix is also quite infatuated). Venosta’s parents are opposed to the romance and threaten to cut him off from his inheritance. Their plan is to “pry him loose” from Zaza by financing a world trip for him.

To cut a long story short, over Benedictine and Egyptian cigarettes, Venosta and Felix work out the ideal solution. Felix will assume the marquis’ identity and go on the trip on his behalf. Venosta is not personally known abroad, and it only takes Felix a few seconds to master his signature: updates he sends the aristocrat’s parents on the progress of his travels will easily hoodwink them.

Once again Felix has a chance meeting on a train, this time bound for Lisbon, on which will hinge the plot, the character Felix’s destiny. He meets Professor Kuckuck, brilliant, eccentric founder of the Museum of Natural History in that city. Kuckuck is returning from Paris, where he has been on museum business. He thrills Felix with elaborations on the philosophy and history of life on earth, and as well, with mentions of his daughter Zouzou, “a completely enchanting child,” upon whom Felix immediately starts to transfer his fondness for Marquis Venosta’s Zaza.

Felix settles comfortably into his new aristocratic persona:

We had hitherto spoken in French; now he inquired: “I assume you speak German, Marquis Venosta? Your good mother, I believe, derives from Gotha — near my own native place — née Baroness Plettenberg, if I am not mistaken? You see I really do know my facts. So we can just as well —”

How could Louis possibly have failed to inform me that my mother was a Plettenberg! I seized upon this new fact as something with which to enrich my memory.

“But with pleasure,” I replied, changing languages at his suggestion. “Good Lord, as though I hadn’t babbled German all through my childhood, not only with Mama but also with our coachman, Klosmann!”

Professor Kuckuck’s truly fascinating discourses create a profound context for implicit questions surrounding the sources of truth and self-hood. The evolution of species traces a mutability in the identity of one species to the next, a process that manifests itself even at the metaphysical level:

There have been not one but three spontaneous generations: the emergence of Being out of Nothingness, the awakening of Life out of Being, and the birth of Man. (271)

And indeed, Being itself, Kuckuck teaches Felix is merely an “interlude between Nothingness and Nothingness.” By this stage, Mann’s novel has created the depth to stimulate a perception of flickering between alternate identities and doubles. Louis and Felix are doubles as independent characters, and Felix is a doubled character himself when he “becomes” Louis the Marquis de Venosta.

These particular doublings are reinforced by the characters’ shared attraction to Zaza, who will shortly mutate into Zouzou, whom Felix-as-Louis will pursue almost as a surrogate Zaza. As reader, we flick through the series of lovers — Genovefa, Diane, Zouzou, Zaza — and with them, the series of mutated, alternated Felix’s. The novel presents the potential for a fascinating action of reading, which is much like the action of the memory in tracing the series of one’s own distinct selves in time.

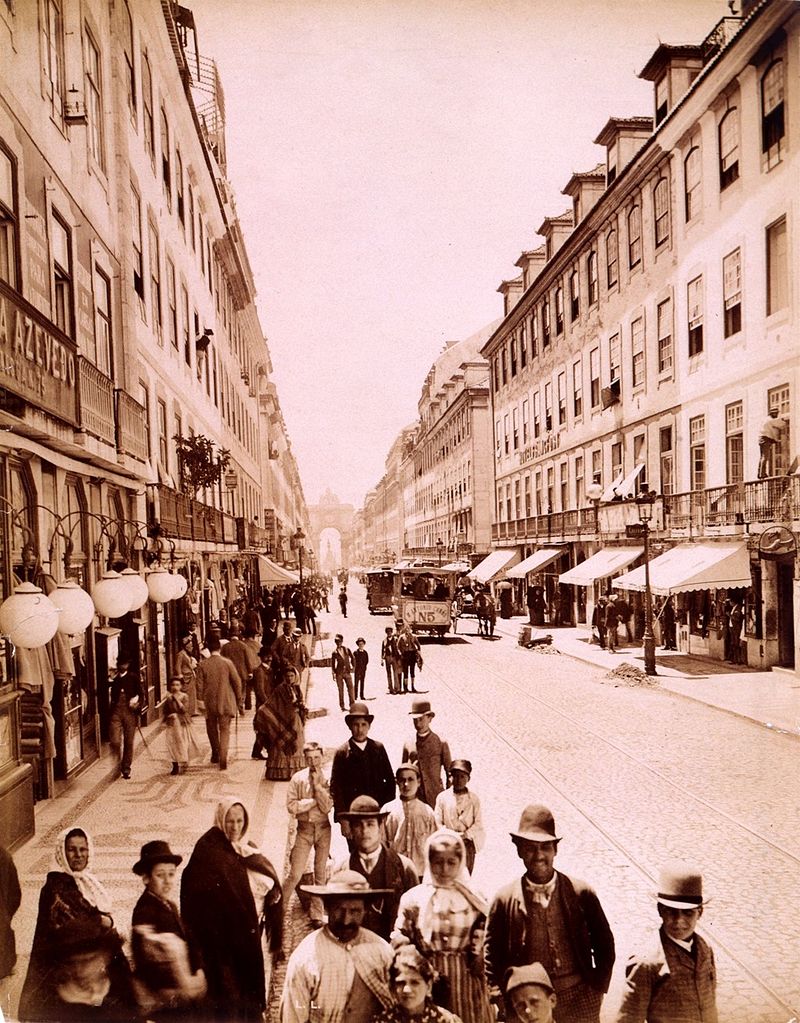

Then, in Lisbon, we are presented with a heightened doubling: Felix and Kuckuck, opposed to the professor’s haughty wife and precocious daughter. In Felix’s coach on the Rua Augusta, on their way to the bullring:

The professor and his wife sat on the back seat, Zouzou and I facing them, and Dom Miguel took the seat beside the coachman. The ride passed in silence or with very brief exchanges, due principally to Senhora Maria’s extremely dignified, indeed stern, demeanour, which admitted of no chitchat.

Once, to be sure, her husband calmly addressed a remark to me, but before answering I involuntarily glanced toward the sombre lady in the Iberian headdress and replied with reserve. Her black amber earrings oscillated, set in motion by the light jolting of the carriage.

Alas, we have run out of time and space in this blog post, so the forbearing reader must research for themself the nature of Felix’s third amorous encounter, fired as the blood is by the adrenalin of the bullfight.

Let me just add that Mann imposes no overt moral judgement on Felix throughout this unfinished novel. Not a plot-like this is what he did and by God he got his come-uppance sort of story. Mann’s assumption of Felix’s narrator-persona is one mechanism that prevents such an abomination from impeding the intoxicating flow of his storytelling.

Neither is there any obvious dark, sinister self lurking beneath, as one suspects of the modern day narcissist — as is borne out by the derivative Tom Ripley character — as enacted in the plot. Rather, Mann’s impeccably subtle technique enables vague hints to reveal the starkness of Felix’s lie when he is at his most articulate, in his erudite, heartfelt, absolutely convincing seduction of his mentor Kuckuck’s daughter, spoken from behind the mask of the Marquis de Venosta.