Death Rites

I am not the least bit afraid of you hungry ghosts, Mow Fung says silently. Not because he doubts your existence, but because he has lived too long to deny it. Still, he will not let you see his fear. A part of him is always apprehensive, and it would be foolish not to be.

In the centre of the back room, the headless body is suspended in light as though in thin air. In the middle of all things, since everything else floats around it, cast into the eternal dimensions. He contemplates the multidimensionality of this container, of the person who once inhabited it, now perhaps having almost arrived at the infinite end of the loop, the point of closure – and escape – of a human entity.

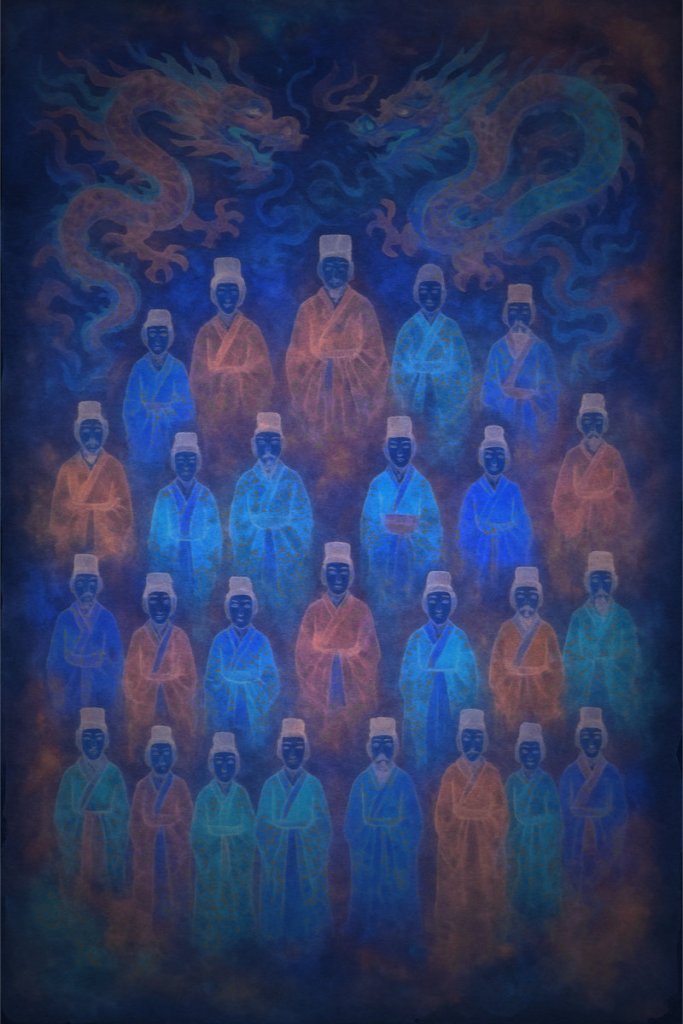

Mow Fung sits on a wooden stool, and images of the ancestors appear to his mind’s eye. Not a grandiose company by worldly standards, not a lineage of Mandarins thirty generations deep. No, some were threadbare hermits, others alchemists in the courts of emperors. Many kept faith with the Tao; others faltered along the way, as he has. Yet all are recorded, nonetheless, in the long cosmic family archive, robed in deep blue, crimson, and jade, and encircled by golden dragons, as befits their rank in the Immortal Registers.

The body is laid out on its back before him, upon a makeshift slab of two small tables joined and draped with a blanket. Only the remains are visible, in a sphere of candlelight. A single flame burns steadily, flickering now and again from some subtle cause, some nearby disturbance. Similarly, the ribbon of smoke from the cheap incense burner placed by the dead man’s shoulder curls and falters, though not a breath of air stirs. Spirits? A lost soul? This man died a brutal death, of a kind that lingers, and draws misery in its wake. The kind of death that attracts attention from dangerous quarters. Yet rites must still be done – from human kindness, and something higher than that. There are dangers, and it has been a long time. But the dead deserve their due.

He sprinkles more incense onto the embers in the burner: dragon’s blood resin, frankincense, myrrh, and sea salt – the mixture taught to him long ago. The smoke rises in slow spirals, vanishing into the rafters. A garden lizard clings to the wall above the window, still as an ancient glyph.

Mow Fung settles into meditation, imprinting the vision of the corpse onto his psyche. Ghosts may bother him tonight. But he will sit, focus his mind, and dream a little.

For the time being, sit here and meditate on this strange and radiant being.

Hungry ghosts may try to devour or deceive the spirit who recently inhabited this shell, may try to beguile him into straying from the true path. So Mow Fung will remain. Perhaps he may be of help to the passing spirit, which surely lingers still.

But I am not afraid of you ghosts and phantoms and all the rest of you, though you may manifest yourselves in the hollows of my psyche and the ancient gateways at the base of my spine.

He will lend the strength of his will and the benevolence of his heart.

Why radiant? What may it be that it radiates? Luminous only in his own mind’s eye? He lets the thought drift past. Inwardly he perceives it again, a pale gleam, the colour of the Golden Pill and Golden Elixir of immortality, the vapour of the Tao inside the body, giving rise to the three flowers that gather at the top of the head. In the eye of ritual he was still recently dead, the spirit hovering close. But the husk declared otherwise, bearing the marks of the sun and the slow desiccation of time.

The skin is dried and darkened to a leathery orange-brown hue, like the crust of old lacquer or parchment scorched by the sun, as though an ancient inscription had blistered and peeled from the body. He lay outdoors under the summer sun for a month to become mummified like this. Mow Fung sniffs the air. Little smell, because the flesh has dried; only a faint foulness lingers. Something has taken the generative parts. By tooth, by hand, by force of hunger or madness, there is no saying. A void where the gate of life once stood, robbed of return. The generative parts: root of essence, seed of Jing. The gate of life torn away.Without the root, the essence scatters. Jing lost, Shen adrift. A cosmological wound, rending the dead man’s passage and the karma of the living he leaves behind. Even ghosts may not find their way back to where they belong.

Around the throat, where once rough red bristles clung, now sun-softened, the remnants of a full beard spread in a matted trail down the chest. Hair grows no further after death; this is his last signature, fading. He leans closer. At the neck: clean, decisive cuts, consistent with a heavy axe. Not just to kill (the killing blow struck the now missing head, no doubt) but to erase. To unname.

Mow Fung stands and moves slowly around the body, passing his hands above it, sensing more than examining as such. The limbs are intact, no bones broken. The calves and thighs hollowed. Scavenged, gnawed out. In the chest, dried flecks of blood cling like pigment; where faint scratches or fragments remain embedded in the skin, their pattern uncertain, whether accidental or intentional. The ribs are bared in patches, the abdomen leached of flesh.

There were dried-out bodies fallen by the wayside on the hot trek from the South Australian coast to the Victorian goldfields. His countrymen, whom he and his comrades would bury with some rites to speed them along their way to the afterlife.

He had seen worse.

One day, long ago in Canton, his feet took him along a meandering route through the city and into an alleyway, where Manchu soldiers were in the process of butchering a throng of hapless supporters of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace. Already the place stank of the blood of hundreds, so many that their heads would not all fit into the chests that were to be sent to the governor general. So many heads that, after a while, many were emptied out of the chests and only the ears packed.

One instant strikes him from the past, clear and lucid as starlight. Two Manchu soldiers bound one of the captives hand and foot and clubbed him so that he fell to his knees. One soldier grabbed hold of the pigtail and the other prepared to chop off his head. Unlike his terrified comrades, the doomed man maintained a calm demeanor. Seconds before the sword fell, he selected Mow Fung from the group of peasants, among whom he had concealed himself, and fixed him in an unearthly, unwavering gaze. It was clear to Mow Fung even then: he had been led to that place to witness this specific moment of death, for his own benefit. Such a pure death signified an enlightened life.

Huish-Huish enters carrying a tray with tea and fruit, as though for a guest. Mow Fung sits, eyes closed, head bowed, his back showing the weight of his years. He remains absorbed in contemplation. Motionless, like a mountain, the mind rests in its place.

“This man is calling out for help,” he says calmly, his eyes still closed. “He is stuck here in the world of the living, still clinging to his physical vessel. But there is something else, something malevolent, reaching from the far past, and out into the future, through this room, at this hour, sucking in all of us. Traces linger here, signs I was meant to see. But to read them, I must first root them in existence. And to do that, I must turn inward, though I have strayed from the path before.”

He makes the arcane hand seal of the Patriarch of Ten Thousand Arts, upon whose benevolence his fate will depend. He doesn’t mind that Huish-Huish sees the forbidden sign.

“Do you mean, similar omens to the ones that came to you in Canton in those lost days, those woeful days far behind you now? Do you happen to recall the ravages of the poppy?”

“Perhaps. There were pleasant times too, you know. Neither matters anymore. But someone has arrived in our hotel needing shelter and a guide. How can we refuse him?”

“Neither matters, according to your beliefs, so do what you feel you must,” she says. “I suppose you will anyway.”

She smiles faintly, turns, and starts to leave the room. Then she looks back.

“Of course,” she says, “you told me you’d fled those times forever. But you know you cannot fly from the path, since the further you fly, the closer you remain.”

“Poppycock.”

Suddenly the incense splutters and the fragrant smoke erupts.

“There are some bad ghosts here now,” he says. “You had better go.” Not entirely sure they are here yet, but she is annoying him with her womanly contrariness, her profound oppositeness.

“Well, don’t worry them,” Huish-Huish says, turning again to go. She is less afraid of ghosts than he, having had less experience. “Don’t surprise them. Don’t scare them too much.”

But there is no surprising some of them, those whom he senses looking on from far in the future, where they have access from their lairs in eternity. Will he have descendants way down the track to help him out if needs be? To combat those vultures who lie in wait to tear out his soul?

He recreates a temporary altar from mystical objects encountered and secreted here and there. With the Sword-Fingers Hand Seal of the right hand, he traces the character Chi or Imperial Order in the air, thereby infusing himself with celestial fire. Appealing to the Patriarch, the deity Wan Fa Zu Shi, he prepares for the journey: painting talismans on his clothes and body for protection, setting upon the altar a peach-wood sword inscribed with celestial characters, and spirit-money, paper painted with black and silver symbols, for burning. How else shall the poor fellow pay his way in the underworld?

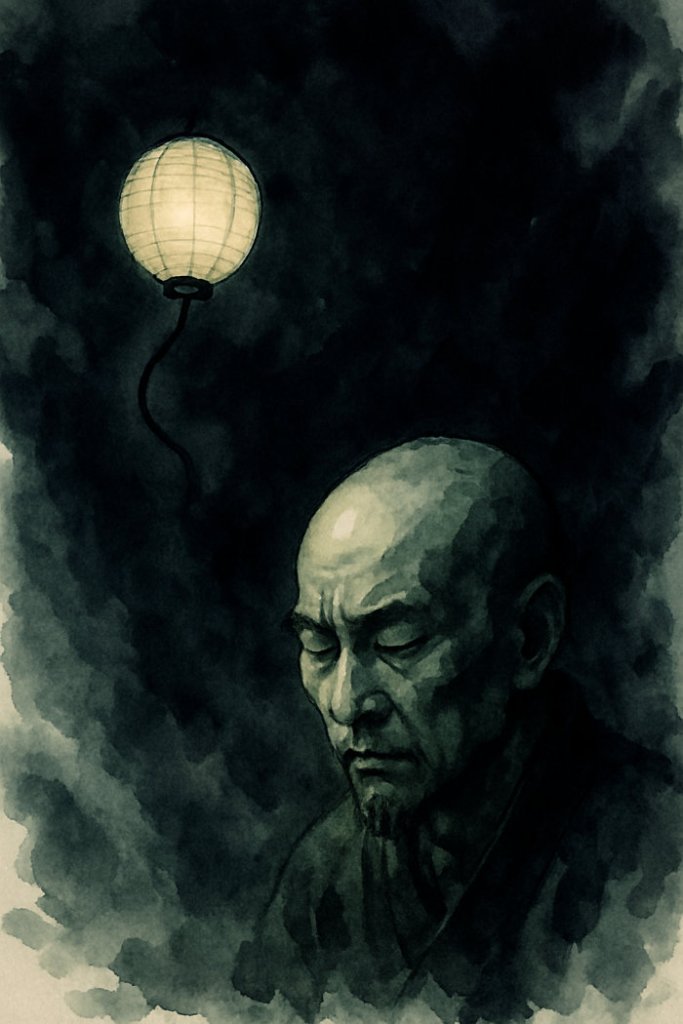

To locate the lost soul, he inflates a consecrated paper lantern with heated air from the candle and releases it through the window, so that it drifts away into the dark. He makes the Five Thunders gesture to resist the threat he smells, from a foul presence, faint but rising. For the rest of the night, he casts spells using the symbols and talismans he has kept hidden away since … he almost forgets when. He sprinkles incense prepared from golden wattle: its essence extracted, purified, concentrated.

He had made the incense himself, as always. The ingredients were chosen for their essences – dragon’s blood, frankincense, powdered bark of the Raspberry Jam Wattle, fragrant and subtly luminous, said to open the inner senses – dried, ground, and purified over slow charcoal in a clay cauldron, with breath and invocation. He had traced the talismanic characters in the air above the bowl: Qi, An, Ling. Then exhaled gently three times to bind them with his own spirit. The resulting powder, dark and fine, was wrapped in yellow silk and set aside to cure in the hush of moonlight. A humble alchemy, but his own.

The ancients taught that to arrive at one’s essence, both substance and self must pass through furnace and cauldron — sacred tools of Taoist transformation, forged in both body and mind. Vessels to burn away acquired dross and reveal the hidden nature beneath.

The incantations first trickle into memory, then the flood begins and he sinks inward, drawn down toward the realm of death. Deeper and deeper.

For some reason this beheaded man made his way here to the Junction Hotel and set Mow Fung’s psyche in turmoil. The story of Peng Yue has haunted him from childhood.

Once a fisherman, Peng Yue became a great general and conquered twenty cities. But the treacherous Empress Lu Zhi betrayed him, and he was beheaded. She had his body minced and salted and fed to the aristocrats who supported him. “I grant you a rare treat …”

Now Mow Fung gazes down from the ceiling upon the headless man on the table. Palms turned down, arms spread at a forty-five degree angle – appearing relaxed, paradoxically, in their state of rigor mortis – legs extended.

He focuses on the trunk and the space where the head once was but is no longer – a void that seems to open outward into infinite time. Even the dead man’s arms express that thought somehow, in their pathetic, unconscious gesture of resignation. He passes through the clogged throat and into the cavern of the lungs; silent chambers sealed by death, yet faintly trembling with memory.

In his meditations, in the stillness of his body, he casts his spells, intones his incantations. No one to hear now but the spirits and ghosts.

Even if I try to move my hand, I cannot, because I feel the pressure of time forcing me back into the reality of this place into which I was born. It is as though an inch of space through which he might move his hand is the same as the whole extent of the universe. So he cannot even lift a finger.

But he enters a trance and moves outward in his spirit body, so that he can follow the lantern, which will lead him to the boundary realm. A dry creek with scrub that Mow Fung does not recognise. The dead man’s ghost appears in the periphery of his vision.

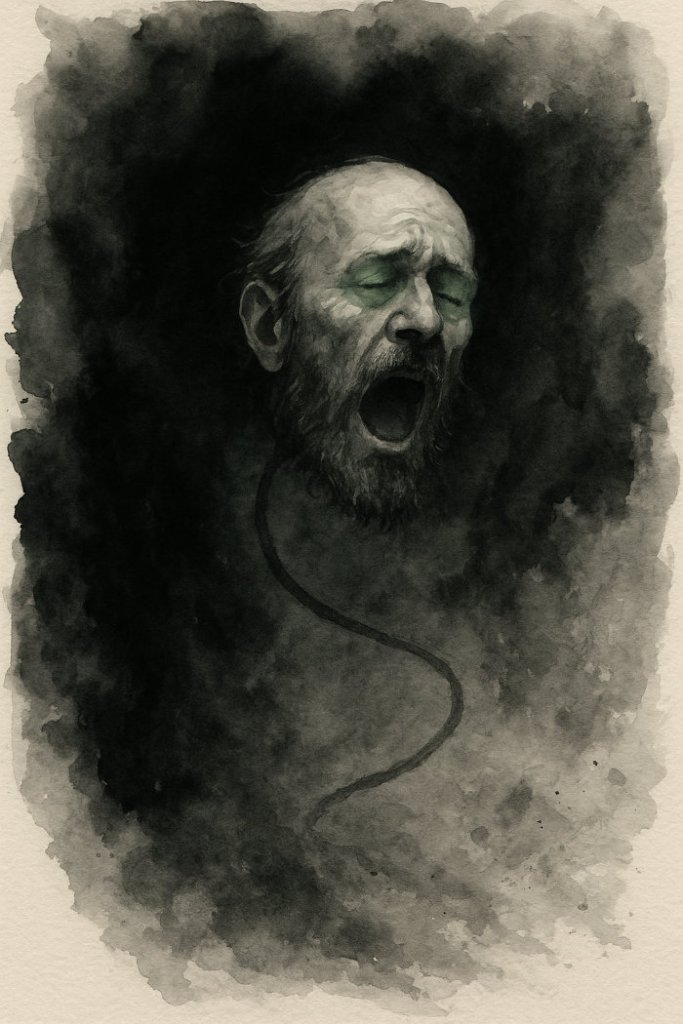

There is the head, but floating, attached by a long cord, moaning inconsolably.

Mow Fung wills him to come along, and so they progress, side by side towards the boundary zone, inhabited by the shadow beings and spirit-shells who prey on the newly dead. The deceased has forty-nine days to get through here, lest he himself become one of the wandering dead, to prey on others.

Along a shimmering trail in a space of blackness beneath two purple moons, they approach the local guardian spirit. Serpents writhe about the three of them in the red dust of the outer limits, while the dark-skinned entity regards the other two askance.

“So you’re that poor fellow with a good mate,” the guardian says to the precarious soul. “I seen what happened, don’t worry. And you, who do you think you are, yella-fella?” looking at Mow Fung. Ink-black skin, white pigment daubed roughly on the face and in lines and patches across his naked body. His eyes strike the alert look of a kangaroo, nostrils flaring.

“You dunno him, wadda you care what appens to im?”

“I have come down here with this bloke,” Mow Fung says, “this white fella, because he came to my place, the Junction Hotel, Deep Lead, dead and beheaded.”

“Irish or Scottish or something. Well, I don’t care who he is,” the local guardian says. “He is where he belongs, under the dirt here. But you, you don’t belong here. You a yella man, a Chinee. You alive still, you can’t fool me, you know!”

He cackles as if finding the situation hilarious. The laughter of spirits is never glib; it is the echo of doors closing – or opening where they should not.

The laugh ceases abruptly, and the guardian’s visage turns to stone.

“You smoked that stuff, them poppies. We don’t want any of them poisons here, so you begone with you!”

“He visited my hotel before we came down here. He may be a sign of worse to come.”

“Good point, maybe. Ha ha! You been here before too, you Chinese man of the dead. We remember you, don’t worry. Only you and that other Chinee.” He raises his arm horizontally to the right and points, without looking. ”You go that way, east, and maybe you’ll find yourself in the west after all. Maybe in the Teahouse of Awakening, where you mobs sometimes meet – if ya lucky, if ya lucky!”

“We don’t want to loiter around here too long, anyway,” Mow Fung says sideways to his companion.

The red-bearded head was making its way back to its place by degrees onto the broad shoulders, condensing midway into the visual field. Disconcerting. Fortunately, Mow Fung had developed his ghost-seeing eyes years before and, invoking the Ghost Eye Hand Seal, was able to discern some dim contours through ripples in the ether. The spirit’s head had descended and he stood there mute, the head bowed, the red hair falling forward to cover the face.

The two of them set off in the direction the guardian had pointed. Mow Fung looked back once and saw a rainbow fading against the black sky.

There are colours that infuse the beginning of things.

There echoed a beating of wings, vast and powerful, as if from a primeval bird.

The entity was gone.

“I don’t know much about these local ancestor beings,” Mow Fung said, “except they are powerful spirits from what they call their Dreamtime. He has allowed us right of way, so if things work out, we might be able to get you through the border zone, out to the other side.”

They reached a fork in the track, marked by a ruined tree. “We’ll go this way.” Taking the path to the left.

The left-hand way follows the yielding earth; the right-hand way, the open sky.

They descended a ridge onto a plain of white ash, streaked with tar pits. Bodies writhed in the viscous black, their groans rising on the hot wind to greet the two arrivals.

Images generated by AI

Leave a comment