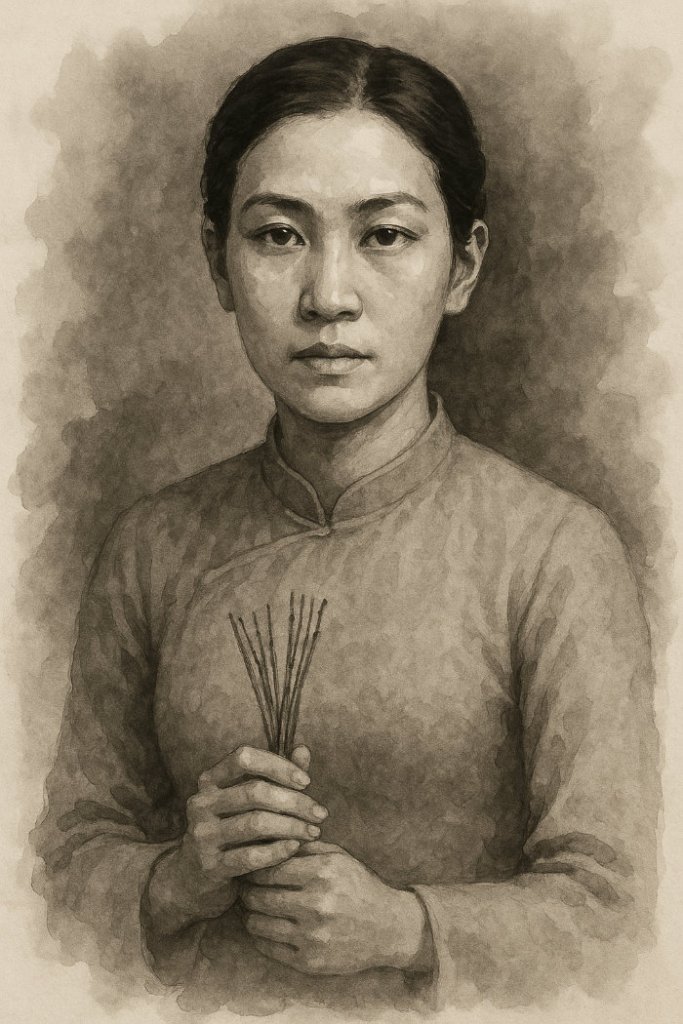

He had been instructing Lena in the secret arts since she was scarcely past the crib. Even then her talent was unmistakable, revealing itself in the look in her eyes, the elasticity of her tiny muscles, the spring in her limbs. How piercingly and wisely she looked at him – and into him! She was an infant when he found her one morning lying in a puddle of tap-water on the floor, his scented pine-soot inkstick ground to smithereens on the purple-red volcanic inkstone, his brushes in disarray but for the one grasped in her fist, with which she was bespattering and daubing all over the floorboards and her own self with energetic expressions of pretemporal flux, the originary Nameless, the mother of all things. Amid her chaos, an image of an embryo? Or was it merely a shape expressed from the dark recesses of his own psyche, imposed upon meaningless blotches and smears?

The prodigious air of equanimity he observed in her at that instant persuaded him the former was true: the form was no accident, but an intentional representation; and this was borne out over time, for as he introduced her to the time-proven techniques and subtleties of the calligraphic art, she would occasionally reproduce similar but evolved versions of the same motif, one after the next.

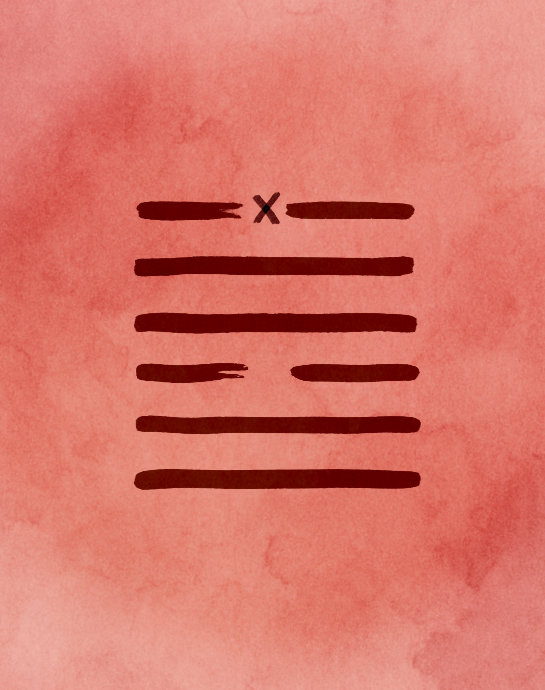

Over the years, the outline became stylised and filled with scenes, blurry at first, then increasingly detailed, as though brought into focus by a kinesigraph, an invention he’d read about in the newspaper, said to have recorded the growth of a universal embryo. As Lao-Tzu’s disciple Zhuangzi wrote: “So all creatures come out of the mysterious workings and go back into them again.” Close by the pair of boulders that marked the feet, two human figures walked side by side upon a waterwheel, driving a stream to flow upward, delineating the spine, which culminated at its point of entry into the skull. Beneath the jagged boulders representing the cranium sat an adult figure, cross-legged.

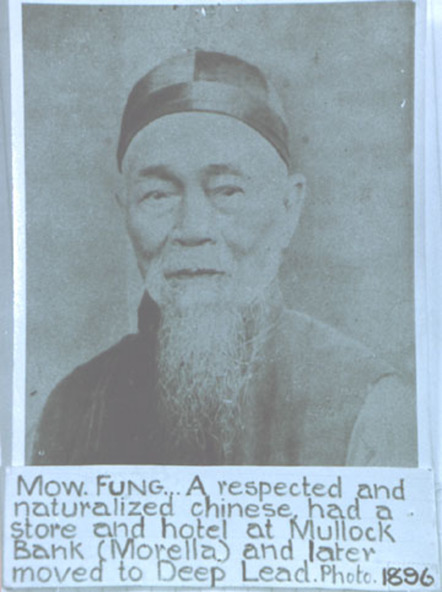

“Who are these children?” Mow Fung asked one day.

“This one is called Yin,” she said, tracing the outline of the girl, “and the other one Yang. Surely you should know that, since you already told me all about Yin and Yang so many times. Aren’t they really, really strong? And they work so hard to create the energy for all of nature, and for human life too. This stream flows east, all the way up to the top of the Southern Mountains, these huge rocks.”

“And this man sitting on the mountain – is it me?”

She emitted a sweet, bubbling peal of laughter.

“Oh no, goodness gracious, that could never be you, although you are very old, like that man; and he sits there doing nothing but contemplating nothing and pondering on things that can’t be named, just like you. Tee-hee!

“Do you know? this man’s mother conceived him when she saw a falling star, and then she carried him in her belly for sixty-two years and he was born when she leaned against a plum tree to catch her breath. Poor woman! But lucky for him, because the plum is an auspicious tree.

“A great crack of thunder erupted, and fairies danced on rainbows high up in the sky. He already had grey hair and a beard and long earlobes like a little old man, and he could already walk and talk straight away.

“That’s why he was called Lao-Tzu, which is a way of saying ‘venerable teacher,’ because ‘Lao’ means ‘old’ and ‘Tzu’ ‘master.’ I think I would have had a heart attack if I’d been poor old Mrs Lao, his mama.

“Truth to tell, with all these wild tales about him, I sometimes wonder whether he existed at all, at least as one real man in history. Maybe he was many.

“Some people think he came down from heaven many times to help humans along the path, and even taught Confucius and Buddha. But perhaps what we think of as the scribblings of one person are the work of several, collected together over centuries. Anyway, my picture is all about making the gold elixir, and becoming an immortal like Lao-Tzu, poor old Mr Rabbit Ears.”

Despite, or perhaps because of, her precocious cleverness, she was becoming rather hard to bear. Not so much so for her parents, who had an inkling of the forces that drove her. Not only had her father cultivated these gifts in her, which were now developing in strange and unforeseen ways, but she was, in some sense, an extension of his own past.

No, he had no-one but himself to blame: his own youthful conceit having left him exquisitely vulnerable to a joke of cosmic proportions, the cosmos apparently having a nose for hubris in those whose gifts were squandered early, especially the inwardly illumined lured by aberrant indulgences, the pleasures of opium smoke among them. Our man had broken a habit to which he succumbed years ago when he fled to Canton, after the tragic deaths of his mother and friends, the three Bandit-Monks as they became known after their years of devotion and training, and their innumerable acts of generosity and self-sacrifice on behalf of the mountain folk. At one time he numbered among the fifty per-cent of Chinese immigrants in Ballarat who were slaves of the poppy, a statistic assiduously reported by government investigators.

• • •

Forward then, into the Underworld, though barely a word forward in a place like this. At any rate, for the sake of argument, best accept the proposition that they proceed, the living and dead, or, depending on an unforeseeable outcome, the earlier and later dead; the guide and follower, though who is which has fallen into doubt.

There had been a lantern, a delicious trembling thing, whose light had coiled around him lovingly, as if loath to depart; but he discarded it after it extinguished in a gust. No, wrong. Impossible: gusts in the abysmal vacuum of this intermediary hell! And yet a stench manages to surface. When, from time to time, the two regain an animal characteristic or other, they are able, after a fashion, to gasp or puke.

The idea of light remains, however, to which they cling, though no sun to adorn the infinitely high and starless ceiling of opaque black. A light of sorts emanates from the earth itself, all about, dull and nausea-green. It is said that this place is nowhere and everywhere, a place where, when the maximum is attained, the opposite is inevitable.

The Sightseeing phase. Here we have the famous Gate of Sighs, unmarked and nondescript, but unmistakable, worn smooth as glass where heads beyond eternal count have bowed low to the stone. Inevitable psychopomp Horse-Face stands to the left, Ox-Head the right. (Or was it Kangaroo and Emu?) One looked on, while the other counted on his fingers, saying nothing, while their minions dragged the two through the dirt, red when it would appear in spasmodic flashes of gaslight.

Clerks of merit and sin pore over their ledgers, spectral bureaucrats assisted by their ink ghosts. They afford few words and barely a glance at the souls. Their avatars would abound in the Colony, haunting the public, despised but obeyed: turnkeys, forever-echoes from the prison cell.

An abysmal semi-skeletal thing in a frayed robe peers more closely at the once-guide. “Still warm,” it mutters, “but the paperwork is complete. All in order. We don’t make mistakes in here” – prompting its indescribably ghastly and abominable colleague to cast it a long blank look, before turning again to its own ledger.

The plain widens, if such a thing were possible in this deathly nowhere, giving way to produce the sensation of a soft tearing into black salient. Surely we are not inside a body… The guide sinks to his knees (ha!), and the larger, redder one, once a cadaver, clasps his living companion’s shoulder and emits an utterance for comfort.

“Take heart. This is meant to be,” he says, surprisingly without any trace of surprise that he has acquired a mouth, and that words come out of it, the inanity of which strikes him the moment he expresses them.

But the once-shaman replies with a desolate moan, for all this not a whit what was intended by him. Pity the hunching, the spasms, as if some mute refusal were lodged at the back of his skull. Voices of the dead are carried in the Whispering Wind: dear companions from the past beseech him to leave the path and rejoin them. And what is this abomination? The innocent voice of his daughter among them, who should not be here by any means! He goes to rise, but sinks again when the voice folds back into the many others, that murmuring desolate weft.

Then this way, onto a plain of hungry ghosts, detritis of failed judgements, souls that neither reincarnate nor dissolve. Disgusting creatures with distended bellies, leech-like necks, and mouths tiny as the eyes of needles, testament to their forever insatiable desires.

At last, he regains the “power” of speech:

“Not this. This is not the shape, nor the measure, nor the place. I am not the one. Stop when it is time to stop. Well, stop!” It is barely a whisper suffused in a sob. “I am not dead!”

“No need to be upset,” the bigger, red one comforts him.

• • •

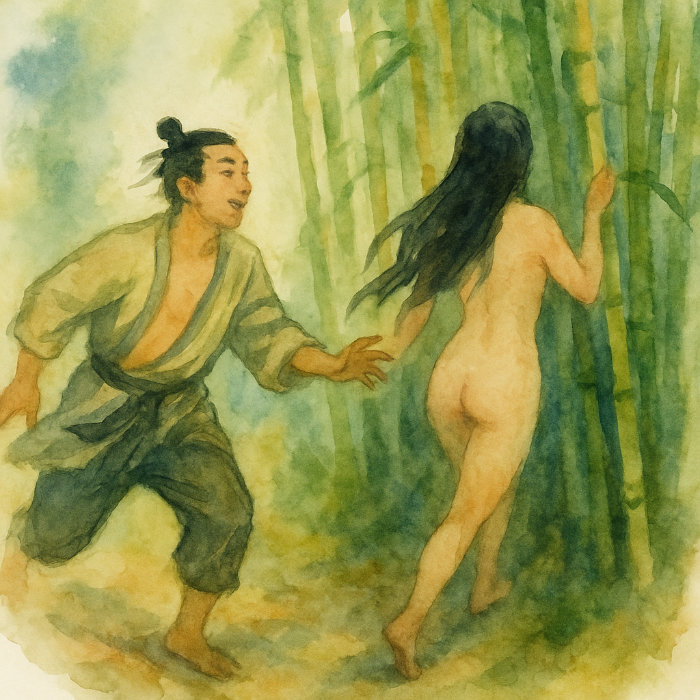

Spurred by the censorious tongue of her school mistress, Miss Pritchard-Jones, in her mid-forties, formerly a Willoughton, Lincolnshire girl known simply as Ruby Jones, some of the locals were starting to turn stony-faced at Lena’s approach, save for the subtle arch of an eyebrow, passed from one to another in discreet recognition. The covert signal was spreading steadily through the European populace of Deep Lead. Miss Pritchard-Jones had paid a Sunday visit to the Junction Hotel with one of Lena’s alchemical paintings under her arm, which happened to depict Yin and Yang in their respective guises of tiger and dragon, in the celestial act of conjoining that occurs at midnight in the alchemical process, when the elixir circulates nine times and returns to the immortal origin. Yes, there above the two fiery figures, the Sword of Wisdom and a once ferocious Monster of Illusion now immobilised with its limbs bound could be distinguished hanging in the stars. Where else could she have obtained such knowledge and imagery? – apart from Time’s Heavenly Sanctuary an Infinity above the Jagged Rocks, to whose archives he himself had long since given up hope of gaining admittance.

“There is something not quite right with the child. She performs dismally on her school tests, though she appears to possess intelligence. Doubtless, she has the ability to ‘go places.’ Many girls of her ability become perfectly capable wives, maids, hairdressers, shop-girls,” the teacher explained after they sat down to a cup of tea. She then hurriedly concealed the painting in her soft leather satchel, before beginning to outline her solution to the problem she believed was vividly immanent in the incendiary artifact.

“Mental and moral discipline are indispensable in the education of a child, else she be led to stray from a productive and righteous path into pitfalls of crime and vagrancy,” she elaborated. “I concede that you in your position, who come from a primitive land and are constrained to a humble, not to say precarious, station in life, in a country that is not always hospitable to orientals and natives, are unable to grasp fully the importance of a wholesome family background to the upbringing and development of a child of Lena’s age, and indeed her siblings …”

The child’s parents looked at her in silence, their eyes stripping back the powdered mask and genteel veils to glimpse the workings beneath – subtle mechanisms, hardened circuits, a cogged and coded puppet, sealed within a larger apparatus of manners and decorum. Her cavernous mouth moved with a life of its own, and her massive, powdered and rouged face inflated to fill the room. Their existences shrank to an invisible plane, and they levitated up to a spot in a shaded corner to observe, alighting like the butterfly in Zhuangzi’s dream. From here, the onslaught softened to the echo of a gale howling in the distance, though her words remained clearly discernible.

“I will put it plainly. Her brain is wrong, her mind astray,” and she proceeded to enumerate several further instances of warped expression that, in her view, had led to the present pass. She paused to take in their reaction but they gave her none. “My concern is that unless steps are taken she will continue to deteriorate – and not only in her schoolwork. By education, we practitioners mean not merely lessons, but all that may be educed – brought out – from the child: intellectually, yes, but morally as well. To begin at the true foundation, one must attend first to the parents. For are we not told, on the highest authority, that the sins of the fathers shall be visited upon the children unto the third and fourth generation? The baser thoughts, emotions, and impulses of the parents find harmful expression in their descendants. It behooves parents to reflect upon their sacred responsibilities.”

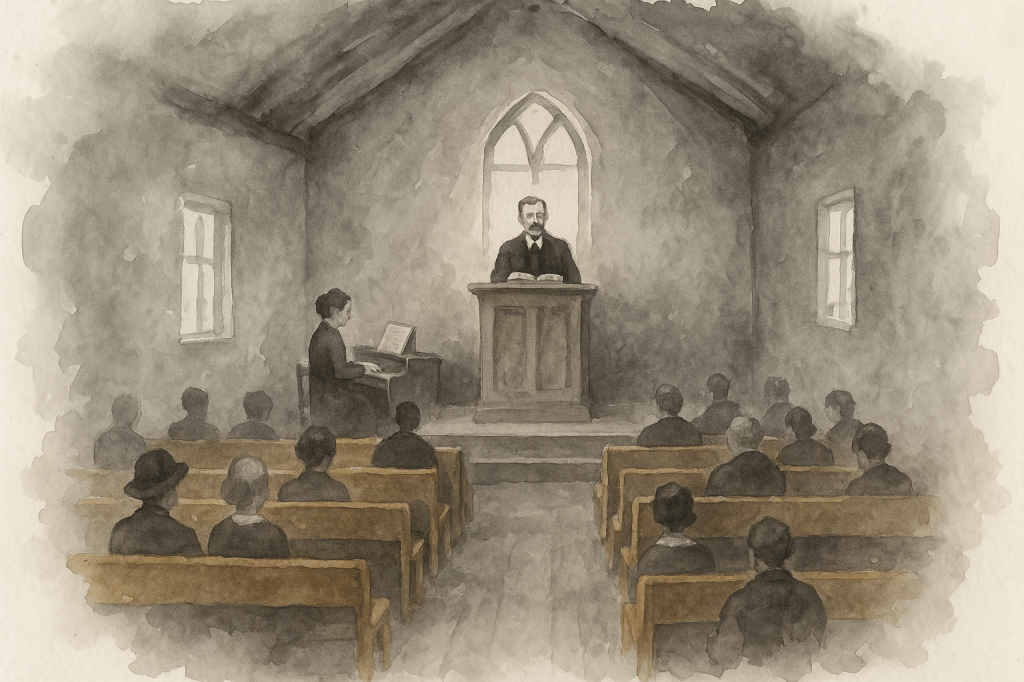

They were more primitive than she had feared. “To quote from Archdeacon Julius’s recent sermon in Ballarat, which I had the honour to attend in person,” she said deliberately, taking out a newspaper cutting from her satchel and laying it down with ceremonial care, “the Lord says expressly that young children are like as arrows in the hands of a giant. From this we may draw the inference, as the Archdeacon explains, that each human life is fired out into the world like an arrow, and just like an arrow, not to miss its mark – by ‘missing its mark’ of course, he refers to sinning – it needs to be keenly pointed, which is to say, trained and sharpened by education. Furthermore, just as an arrow has three feathers, the three stabilising forces for a young life need to be: knowledge, love, and work. And so on and so forth. I would like Lena to take this and read it closely and explain it to you both thoroughly, so that all of you can understand. And I have a proposal …”

A faint breath, a stirring as if by the wing of a moth, made Mow Fung aware that his eldest had joined them up at the cornice.

“Yes, bring it in,” he transmitted and lowered his full awareness back into his corporeal body.

“It is a well-known fact that poorer parents tend to coddle their children more than the richer, and the children tyrannize them in return.”

“Something in what you say there,” Anna said with a smile.

The door squeaked open and Lena entered with schoolroom poise, carrying her current work of art: black crayon on a sheet of wrapping paper. A figure seated cross-legged, spine straight, balancing the sun on one palm, the moon on the other. Within his belly, a stove glowed, its tiny flame drawn with a child’s fierce precision. The girl set the picture on the table without a word and assumed a still posture.

Miss Pritchard-Jones’s smile did not quite reach her eyes.

“And what do we have here, dear?” she asked sweetly, leaning forward to squint at the drawing, as though it almost certainly contained something improper.

“Is this meant to be… a magician of some sort?” the schoolmistress tried again, tracing the black line that circled the figure’s stomach. “Or perhaps… a new kind of stove?”

“It’s just a man,” Lena said.

“He seems to have swallowed a brazier,” said Miss Pritchard-Jones, letting out a snort of mirth – which, after a glance at the girl’s father, anticipating that he would share her amusement, she immediately stifled.

Mow Fung looked at the drawing for a long moment, then at Lena. The silence stretched.

“Why do you think his eyes are crossed, Miss Pritchard-Jones?” Mow Fung asked.

“Goodness gracious, there is no why or wherefore about it. All nonsense.”

“Lena?”

“His eyes revolve like the planets in the solar system, Miss Pritchard-Jones. He squints and then rolls his eyes from left to right and back again to raise and lower his inner fire. From left to the top of his head, then down to the right to look inside his navel. He rolls his eyes around the sun thirty-six times to raise the positive fire. Twenty-four times around the moon to lower the negative fire.”

“Incorrigible,” the teacher said.

“Yet, you must admit it means something to her, and you see how she has learned your schoolbook science.” Then turning to his daughter, “Miss Pritchard-Jones has a proposal for you, so pay attention.”

“I shall listen and obey, Father.”

The woman struck a declamatory attitude.

“It is true, parental responsibility involves the proper training of each child by its parents, but this is the ideal not always reached. Unfortunately, we do not have sufficient resources at the Deep Lead school to provide the religious instruction so sorely needed in a case such as this. However, as a Teaching Elder of St. Matthew’s in Stawell, I have taken it among my broader civil responsibilities to provide extra-curricular religious training and discipline to a small group of lucky young people deemed most in need of healing, in what I make bold to refer to as sessions of spiritual therapy. Spiritual wellbeing is as important to a child as their physical wellbeing and should never be neglected, lest the child herself be considered neglected.”

Lena made her opinion clear immediately upon Miss Pritchard-Jones’s departure.

“If she thinks I’m going to traipse all the way over to Stawell every Sunday to listen to more of her tripe, she’s got another damn thing coming.”

“You should think about making an effort to fit in,” her mother ventured. “When turtles hide in the mud they remain safe and cannot be harmed. When they come out, people catch them. Same with fish. When they stay down deep, nothing can hurt them; but when they surface, the birds catch and eat them.”

“Yes, best be like the turtle in the mud, the fish in the deep,” her father agreed, “Who knows? – there may be things worth learning in this spiritual therapy business.”

“Don’t worry,” Lena said, “I’ll take care of it.”

The next evening, there was no one around to notice the slender shadow flit through the laneway that ran alongside the teacher’s residence nearby the Deep Lead school, nor the flash of a match igniting a rectangular slip of paper, which burned for a few seconds to ash. The ‘Five Ghosts’ talisman works to traumatic effect when exercised against susceptible victims of a sensitive disposition, but Miss Pritchard-Jones was not such a person. Moreover, the artificer of the talisman, though youthful, was a compassionate girl, and inscribed it with characters that summoned less insidious spectres. No terrifying flying-head ghosts, faceless ghosts without feet, or baleful hungry ghosts from hell. Instead of these, naughty, playful sprites, who on the completion of each childish prank would depart back into the spirit realm to the tone of a chime, leaving no more than that playful and well-intentioned vibration. Just the type of spiritual therapy that might do her teacher good. Little harm likely ensues when a goldfish goes missing from out of its bowl but reappears a day later unassisted, looking as though nothing has happened; and the same is true of a budgerigar from its cage. Then a pet rabbit absconds leaving its cage door wired shut behind it, lagomorphous version of the Davenport Brothers, the famous mystical escapologists. It fails to return; but perhaps this is far less than a miracle, given the hatred for its species throughout the Wimmera at that time.

Resting on her beloved rattan chaise longue on the veranda, Miss Pritchard-Jones looked up when the Fung child appeared, cradling the pet rabbit she had found hopping aimlessly on the roadside. The girl gently placed it in her hands. There was enough empathy in Lena’s eyes to still the suspicion, barely forming, that she might somehow have been responsible for the escapade – which indeed, she was not, at least in a certain direct sense of the word. The teacher smiled and patted the girl’s hand; her need of spiritual therapy was never again mentioned, and the tinkle of the teacher’s little Aeolian chime was from that time only ever heard when a gentle breeze, at least, would stir. A past offering from an anonymous pupil, the Japanese curio could be obtained at Kwong Hing’s shop in the Chinese camp.

• • •

A flat place. No texture or edge. Suggestion of enclosure without form. Inner perimeter, no wall. The air is not air as such. Breathing is not a prerequisite. And yet there is a pressure from above, faint but definite, of eternal waiting.

A pale thing leans. A figure, perhaps, or a coagulation of posture. It inclines forward from among a stand of not-columns. Not arranged, not formed, neither standing nor collapsed. The pale thing has no face, or a great many, vaguely superimposed. It carries the smell of ancient, unwashed robes, and the fungal tang of mouldering rice-paper: suggestive of a monolithic bureaucrat obsessed with the accounting of infinitesimal infractions.

It speaks: “Proceed.”

Silence. Then again: “No. Abide.”

The Celestial lowers his head even lower. The other stiffens. Progress may no longer be an option for him.

“There is a discrepancy,” the thing says. “Designation uncertain. Misprocessed? Unprocessed?”

It shuffles what appears to be a sheaf, but the papers are not quite flat, and not quite still. One separates, drifts, curls at the edge before floating down to a non-floor, sizzling to ash.

“State your designation.”

No answer.

“He is not dead,” explains once-Forbes.

The thing tilts. Abides. Tilts again, as if abiding might yield reply.

“He is here. There is no procedure for reversal.”

Mow Fung emits a sob.

Nothing changes.

Then: “Though I suppose even that may be subject to review these days, the way things are going. We will open the Register of Residual Appearances (Beings Undead or Vanished.)”

It does nothing.

“Ah. Yes. An echo. The shadow of an intention. The residue of action restrained. A karmic hesitancy.”

It does not look up.

“He may proceed.”

Then, as if mumbling to itself. “Unless the next phase has been canceled… We received a memorandum but the seals were indistinct. The authority unclear. Proceed. If that is the word.”

Not a soul stirs.

• • •

One day, she looked up from a swing he had hung for her years before, from the low branch of the blue gum behind the backyard, studied his face seriously and said: “Father, I am ready.”

“For what?”

“I don’t know yet exactly for what.”

“Well, I shall have to save to buy you a violin or something.”

She looked at him with a long-suffering expression, but did not answer.

“The Maiden spoke to me when I was watering her. She gave me quite a shock, but I heard her voice distinctly.” The Maiden was the title they gave the stateliest maiden wattle in the acacia grove. Acacia maidenii was the plant’s Latin name, she informed him.

“Oh?” The plants had never spoken to him, though he paid respects, and certainly watered them more dutifully than his number one daughter.

“What did she say?”

“She said there was something I must do.

“Oh?”

“She said there were some things you have to do before she’ll be able to speak to you directly – some procedures – and then you will be able to tell me what she said. I understand much from her, but there are other things I need you to explain.”

“What are these procedures?”

“First, you should get a pencil and paper. Have you been squinting properly?”

He found the stub of a pencil and an old envelope in a shut-off area of the bar he called his office. She related to him the means of extracting potions from the maiden wattle, which would show him a new, deeper path than the one from which he strayed, even before leaving China. “This is the best way to use the bark and roots here,” she said, and summarised the procedures for him, drafting some diagrams in her precise hand and noting down Chinese names for some substances that she could not possibly have learned except from an adept in alchemy or sorcery.

He explained about the tree spirits and malevolent wandering ghosts. Some plants and trees develop a natural spirit of their own – a spirit-being inhabiting the stem or trunk, like a tree fairy. These are far more powerful than common ghosts and spirits, though usually benevolent. Sometimes, however, a wandering ghost may take possession of a tree and impersonate a natural spirit. These are dangerous. Homeless ghosts that settle in innocent trees can harm human beings, and people must be wary of them.

“I understand all this,” she said. “The Maiden explained to me I was a wise and ancient being.”

“I thought I told you that.”

“Not in so many words.”

“Oh.”

“Now, try to listen and not be dense.”

He gave her a paternal look, an eyebrow raised.

“The Maiden told me to say that,” she said with a look of surprise.

“That’s all right,” he said. “I suppose I’ll have to learn when it’s you being cheeky yourself.”

“Now come with me to the acacias.” And he went with her to his special garden.

“Your arts are a little outdated,” Lena said. “She says that her cousin acacia pycnantha is so popular and beautiful that she will likely become the flower symbol of this whole country. She has such magnificent golden blooms, and we love her wattle-seed cakes and biscuits. The Aborigines, she says, use her wood to make spears and boomerangs, and put her leaves and bark in the billabong to make the fish go sleepy, so they can catch them easy. They use her smoke as a medicine, too, for things like diarrhoea and inflamed skin.”

“Oh yes, of course, of course.”

“Please stop looking at me superciliously. She isn’t fond of sarcasm, in fact she loathes it.”

“She told you that?”

“Nor fond of the faintly ironical tone you affect at times, she said just now.”

“Oh.”

“She knows a lot about you. She knows about the Jade Volume in the sanctuary above the jagged rocks, and about your friend in China the mighty general Senggelinqin, and the story about your mother and the bandits, and the opium, and how you came to Australia, and tramped all the way from Robe to Ararat, before coming to Stawell and Deep Lead. She knows a great deal.”

“I think I told you those stories myself.”

“She showed me inside my mind, I think, or in a dream, in moving pictures. It was like I was there, sort of thing.”

From the draft novel Stawell Bardo © Michael Guest 2025