Sometimes the anomalies in a text can provide a starting point to explore possibilities of meaning that aren’t immediately evident. The first such a one in this chapter is striking: Smith’s misquotation from Romeo and Juliet, which ought to read:

These violent delights have violent ends,

And in their triumph die. (2.6)

An erroneous word, “transports,” conceals both the true terms “delights” and “triumph,” as though they fall into a conceptual blind spot. “Transports” is a distinct concept from the others, denoting the sense of an ecstatic loss of control, which is absent from the actual terms. At the same time, it is illogical that “transports” (of caprice) die in their own “transports,” as the misquotation circularly proposes. The quote seems to summon the virtues of self-restraint, but in a mere rhetorical gesture, one that lacks sufficient conviction even to check the logic.

We assume that an alternative species of love will endure — “true, manly passion” he calls it. An issue of true love flows beneath the ensuing narration of the perennial courtship ritual, reenacted by two youthful couples. The narrator’s perspective, which he assumes the reader will share, is self-assured and authoritative — one of disengagement, having access to the superior wisdom of age. Just as pointedly, the narrator’s point of view is one of retrospection, that of an elderly man looking back upon his own youth, and applying to the young those realizations beyond their grasp, which can only be acquired with time and life-experience.

Such an ever-so-slight but unmistakably condescending tone colours the narrative, this erroneous word “transports” loaded with a pejorative sense of “ecstasis” — a being beside oneself, being taken or stepping outside the self, as in a rapture or trance: a danger to which youth is singularly vulnerable in matters of sexual love. The courtship and fate of Romeo and Juliet exemplify the transcendence and peril. (Let’s overlook the later underwhelming allusion to Juliet assigned to Lady Kate: “Parting is always sad.”)

A further anomaly is the conspicuous mention made of the Greek lyric poet Anacreon (c. 582 – c. 485 BC), whose brows were “crowned with snow,” says the narrator (in Anacreonic mode), when he wrote his love poetry, though the topic is the young William Whiston’s attempt to express his passion to Kate in verse — but not only in verse. Anacreon’s relevance would appear to be not so much to Willie, however, as to the narrator, as a proxy for Smith himself, who finds himself here “cheering his age” with the remembered sweetness of past love.

We can assume a degree of familiarity with Anacreon on the part of Smith’s ideal reader. Thomas Moore’s (1779 – 1852) Odes of Anacreon, Translated into English Verse with Notes (1800) spawned a vogue of ‘Anacreonics’ — the art of imitating Anacreon — among further Irish and English poets, expanding a more minor European tradition that went back several centuries, an ancient tradition of erotic verse. Poets of such significance as Byron, Shelley, Keats, Coleridge and Wordsworth took one interest or another in the Greek, who was “one of the original lyricists of wine, women and song” (Jane Moore passim.)

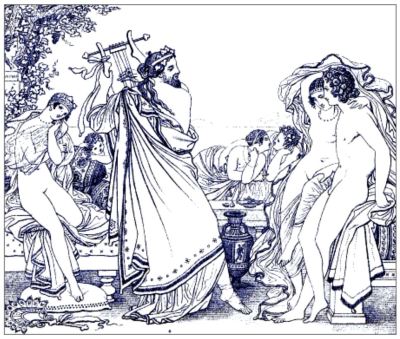

For a sample, let’s see Thomas Moore’s translation of Ode XVII, as illustrated by the French Anacreonic translator and artist Girodet de Roussy (1767 – 1824), said to have captured the essence:

Now the star of day is high,

Fly, my girls, in pity fly,

Bring me wine in brimming urns,

Cool my lip, it burns, it burns!

Sunn’d by the meridian fire,

Panting, languid I expire!

Give me all those humid flowers,

Drop them o’er my brow in showers.

Scarce a breathing chaplet now

Lives upon my feverish brow;

Every dewy rose I wear

Sheds its tears and withers there.

But for you, my burning mind!

Oh! what shelter shall I find?

Can the bowl, or floweret’s dew,

Cool the flame that scorches you?

Here Anacreon, like Smith’s narrator, facilitates the encounters of two imagined couples, except in an explicitly voyeuristic rite, all the signifiers in free play. Symbolism of humid flowers, burning of lips, scorching of flames, wearing of dewy roses. Nothing like a good orgy in the middle of the day.

Turning now to the more prosaic scene, structured by Victorian proprieties, we are a little sensitive to the fluttering hearts, a smouldering subtext beneath the cut and thrust of Lord Bury and Clara’s repartee and ripostes, undercurrents of love yet undeclared. Similarly in the circular drawing-room, William’s love sings his Anacreonic lyrics, his urge to break out of the restrictions placed upon his burgeoning passion.

It’s more in keeping with the Smith we have come to know, the wine-imbibing Bohemian wanderer. Not the fuddy-duddy uncle who sits “playing propriety,” putting a damper on this youthful excitation, but that wag who blew up the Mississippi river boat and elevated a printer’s devil.

Wine, women and song? Hell, you can drink and sing any time.

CHAPTER TWENTY

A Lesson on Prudence — Clara Meredith’s Defence of her Friends — Love Vs the Absurd Teachings of the World

When a man begins to feel puzzled as to the nature of his feelings towards a woman, we may feel assured that something akin to love is mingling-with them. He may not be conscious of it; in fact, we very much doubt if any male creature was ever yet perfectly aware of the heart’s entanglement till the net had become too strong for its meshes to be broken.

In speaking thus of love, of course it is to be understood that we are describing it in the true, manly, common sense of the word, not of those sudden caprices to which Shakespeare alludes when he says

These violent transports have violent ends,

And in their transports die.

Lord Bury began to feel a strong but, as he conceived, purely platonic friendship for his cousin Clara. There had been no attempt to catch him, no efforts to attract; great points in the lady’s favor. Although, like most young men, a great admirer of beauty, it ceased to charm as soon as it becomes demonstrative; like the magnet, it had two poles — one to attract, the other to repel.

His lordship was fastidious in his tastes, as might naturally be expected from his education and the surroundings of his youth. Fortunately he possessed a safeguard in those high principles which most certainly he had not imbibed from his father, whose profligate example failed to corrupt him, as an overdose of poison sometimes fails to destroy life from its excess.

Clara Meredith and Lord Bury were conversing in the conservatory at Montague House, whilst their cousin, Lady Kate, was giving a lesson in music to William Whiston, now a constant visitor in the circular drawing-room, where Martha, who shared the peril and flight of her young mistress, was seated at a distance to play propriety.

‘Hush!’ said Clara, interrupting the conversation with her cousin. ‘How perfectly their voices blend together!’

‘Too perfectly!’ observed gentleman, dryly.

‘Bury,’ replied the lady, ‘that is really the first ungenerous word I ever heard you utter. I thought you liked her preserver.’

‘And so I do,’ continued her cousin, ‘like him for his perfectly unaffected manners, his plucky perseverance at the university — the studies would have killed me — the reputation he has already acquired, and his fixed determination to win a name.’

‘Win a name!’ repeated Clara. ‘Why he has one already.’

‘Ah, indeed!’

‘And you know it as well as I do — William Whiston.’

‘I cannot find it in the Herald’s books,’ observed his lordship.

‘Possibly,’ said Miss Meredith; ‘he wishes to avoid bad company — a great many bad names there. Seriously,’ she added, ‘you are ungenerous — unlike yourself.’

‘You think that I am naturally generous then?’

‘Yes,’ replied Clara, ‘when you speak and act for yourself, I mean your real self, and not from the prejudices of the world. Why should he not be received here? The service he rendered Kate was immense; his family is respectable, his character without reproach, his talents undeniable.’

In the warmth of her defence of the absent the speaker had risen from her seat and was about to leave the conservatory.

‘Come and sit by me again,’ said his lordship. ‘We must not quarrel; that would be too absurd. Let us talk reasonably.’

Clara Meredith silently complied with his request, yet felt angry with herself for doing so.

‘Thanks,’ said her cousin. ‘I knew you would not judge me unheard.

‘But I have heard you —’

‘Only partially,’ continued the gentleman. ‘Recollect there are two sides to every medal.’

‘And to most faces,’ added her cousin.

‘An epigram!’ exclaimed her cousin, archly.

‘I did not intend it for one,’ continued Clara. ‘Merely an observation. You know I never can disguise my thoughts, and would not if I could, unless to avoid giving pain to these I love,’ she added.

The young guardsman began to feel a wish to be one of those she alluded to.

‘Clara,’ he said, ‘I cannot endure to be misjudged by those whom I respect. Listen to me calmly.’

He took her hand in his, and the heart of the young girl began to flutter wildly.

‘It is not our fault,’ resumed the speaker, ‘that we are born in the rank and privileged station that we hold in the world.’

‘Nor our merit,’ was the reply.

‘Granted,’ said his lordship. ‘But having been born to them, it is our duty to fulfil the obligations they impose upon us.’

‘Some of them. A broad charity in estimating the worth of others, and a helping hand not only to the poor and humble, but to all who by cultivation, intellect and honourable industry are seeking to escape the trammels of prejudice, the worldly jealousies which would cuff down rising merit, clip the wings of the young eaglet, to prevent its soaring to these nobler heights where fortune’s owls are perched in idle security.’

‘These are strange doctrines,’ observed her hearer, ‘for one of your age and sex.’

‘I cannot help it, coz. They come naturally to me.’

Lord Bury rose from his seat, paced the length of the conservatory, then turned and reseated himself by the side of the speaker.

‘You approve, then,’ he said, in calm, dispassionate tones, ‘in your cousin, Lady Kate Kepple, the last descendant of an ancient and noble race, falling in love with William Whiston, the son of an obscure farmer? I grant that he is honourable; not a speck upon his reputation. I have ascertained that.’

‘I am not aware that there is yet any question of love between them,’ answered his hearer.

‘Aye, but there is, or at the very least a danger. I have watched them closely, Clara. His tongue may have been mute — I trust it has — but his eyes, those windows of the soul, are eloquent. He will declare himself,’ he added, ‘and that is the danger I wish to guard against. You, too, have seen it. It is useless to deny it. I have watched you both.’

Clara Meredith began to feel extremely embarrassed. The words of the speaker were not without influence on her prejudices. Education was to blame for that. But they failed to shake her principles. There she felt firm as the rock of reason on which they were based. Conversion at the swiftest is but a slow process, the world has so many ties to draw us back, to stifle our best instincts. Clara was too truthful to deny the uneasiness she had long felt on her cousin’s account. As yet she knew nothing, if she feared much. She felt that the speaker was treading upon treacherous ground, so, with true feminine instinct, she hastened to change the position.

‘I am perfectly satisfied,’ she said, ‘that Kate will never disgrace herself by contracting an improper marriage.’

Lord Bury smiled. He was not much of a logician, but he detected the ruse.

‘An alliance with meanness, with vulgarity, sordid interest. She has a sensitive nature; pride almost equal to your own, Egbert. None but a true heart could win her.’

‘I am as firmly convinced of that as you are,’ observed her cousin. ‘Whiston possesses the quality you name. I do him that justice. Were he a mere scheming adventurer, I should feel perfectly easy on our cousin’s account. More, he is gifted with rare talents, and that still rarer quality, perseverance. Therefore I fear him,’ he added.

‘As a rival, perhaps.’

‘Pshaw!’ ejaculated his lordship, impatiently. ‘You know me better than that. I never thought of Kate on my own account.’

‘What is it you fear, then?’

‘A misalliance in our family.’

‘Oh, you men! you men!’ exclaimed Clara, impatiently, ‘with your pride of rank, your worship of a mere accident, your absurd veneration for musty parchments and the Herald’s blazon! You laugh at our sex — the weaker one, as you insolently term us — for our love of bric-a-brac, majolica, Sevres, antique lace and niello, whilst with admirable inconsistency, you bow down before idols which have not even artistic beauty to recommend them.’

‘If you advocate Kate’s cause so warmly, I shall begin to think you share her weakness.’

‘That was a most ungenerous thrust,’ observed the lady coldly, ‘and unlike yourself, because it was discourteous. If there is one quality more than another which I like in you,’ she added, ‘it is your perfect tone and manner with women. I should regret being compelled to change the opinion I have formed of you; very sorry.’

His lordship felt the reproof all the more from the consciousness that he had merited it. He was gratified also by the compliment with which she had withdrawn the sting.

‘Let us change the subject,’ he said. ‘I perceive I shall not have you for an ally. Let what will happen, we must remain fast friends, coz. I cannot afford to lose you and Kate; it would leave a void in my existence greater than you dream of.’

Clara blushed at the words — which might have meant much or nothing. Reflection — for she had a very humble opinion of her attractions — convinced her of the latter. Still, she treasured them in her memory.

Whilst the above conversation was taking place in the conservatory, one far more eloquent, because far less worldly, occurred in the circular drawing-room, where Lady Kate Kepple and our hero had been practising a duet together. William was about to return to the university, and each knew that nearly a year would elapse before they met again.

Poetry and music are the keys of the heart — fortunately, there is sometimes a third one, which fetters its voice in silence — prudence; not that it is always sufficiently strong to guard the tongue from uttering the words that quiver on the lips of a true, manly passion. Feeling often becomes too powerful to be governed by self -imposed restraints. A look, a sigh, and, still more frequently, a tear, will break the strongest resolution. In age we can reason on these things calmly, else it would be impossible to describe them truly.

The brows of Anacreon were crowned with snow when he wrote his passionate love-verses. The realities had passed; but the dream, like the exquisite perfume of some precious flower, remained to cheer his age with its remembered sweetness.

William, who had won the chancellor’s medal for the prize poem the preceding year, wrote a few lines on the subject of his approaching departure, which, in a rough, unscientific way, no doubt, he contrived to set to music, then sent them to Lady Kate, modestly requesting her to correct the music for him.

‘Artful,’ we hear some of our fair readers exclaim. Perhaps it was; but, if so, it was artfulness without craft— the artfulness of nature. It is scarcely necessary to add that the grateful girl complied with his request — the words touched her more than she would like to have confessed, and the simple, unskilled melody to which the youthful author had set them haunted her. Were it averred that she murmured it even in her sleep, we should scarcely doubt it.

This was the composition, which had so strongly excited the suspicions of Lord Bury and created considerable uneasiness in the mind of Clara Meredith, who knew the world and shrank from its sneers, although in a just cause she felt that she could brave them.

‘I think I have succeeded,’ observed Lady Kate, when the poet hesitatingly presented himself in the drawing-room. ‘I have arranged it as a duetto.’

‘The very thing I most desired.’

‘You can look it over,’ added the fair girl, pointing to the sheet of music upon the pianoforte; ‘afterwards we will try it.’

Little did she suspect the snare she had prepared for her own heart.

Sufficient to add that the arrangement was gratefully approved of, and they commenced singing together:

Farewell! Farewell! I would not fling

Around thy brow the veil of sorrow;

Brightly for thee the morn shall spring,

And mirth and music wait thy morrow.

I dare not leave one parting token,

Or breathe a sigh of vain regret;

Dream not the word I leave unspoken,

Or if thou dost, thy dream forget.

The poet seeks his cloistered hall,

Thy home will still be beauty’s bower;

Should memory his strains recall,

Forgive the madness of the hour.

Twice had the youthful singers repeated the strain which betrayed the feelings they dared not express. On the last occasion the rich voice of our hero trembled with emotion, but with a strong effort he mastered himself, and a silence more dangerous than words ensued. Kate was the first to break it. Strange to say, she had been more successful in suppressing all outward signs of agitation than the youth who so truly and, as he believed, hopelessly loved her; that exquisite reserve and sensitive modesty which are a girl’s best safeguards restrained her, for William had never hinted at his passion before — he considered it hopeless, and no true woman ever yet could bring herself to acknowledge she had, unsought, been won.

Kate was the first to speak.

‘Parting is always sad,’ she observed, ‘especially from those we esteem; but you must not feel its pangs too keenly. Consider it but a cloud obscuring the bright morning of your young life. Your good, kind uncle, who loves you like a son I am certain, views the separation as I do. The cloud will pass,’ she added, attempting to force a smile, ‘and all be fair again.’

‘I was not thinking of my uncle,’ observed our hero; ‘and yet I feel most grateful to him. I shall find him unchanged on my return, even should I disappoint his expectations.’

‘Doubting yourself, Willie,’ resumed the object of his thoughts. ‘Is not that unwise? Why even I, who am a poor, weak girl, possess more courage and hopefulness than that. I am not a judge of such things, but every one tells me the highest honours of the university are within your reach; and in this land, where there are no barriers of caste that may not be surmounted, we know what they lead to. I speak not of wealth, but of the world’s consideration, respect from the respected. The senate and the bar have long been ruled by men who won their way as you will do.’

‘They have ceased to attract me,’ observed her hearer, sadly. ‘I have fixed my heart upon a prize so immeasurably above my reach that even hope is denied me, like the golden apples of the fabled garden, it hangs so high above my reach I can only gaze wistfully at a distance. Life,’ he added, ‘has lost its best incentive to exertion.’

‘Patience,’ said Kate, scarcely conscious of the import of the words she uttered, ‘patience and perseverance, and the branches will descend to you, borne down by the weight of their fruit.’ Then, as the sudden flush, the flashing eyes of her lover betrayed the construction he placed upon her speech, broke upon her mind, she hid her face in her hands.

In an instant he was at her feet, pouring forth a torrent of impassioned words all the more eloquent for having been so long restrained. We cannot trust our pen to repeat the words in which he clothed his feelings; they would appear cold and vapid to those who never felt the pangs of a true love, whilst to those who have felt them they are unnecessary.

A true passion, like Proteus, takes many forms, but the same soul animates each. Love is a mighty lord indeed; gentle as a child, despotic as an autocrat by turns. Poor Kate had resolved to be very reasonable — in fact, she had been so; for what can be a higher exercise of reason than to place our affections worthily!

‘William,’ she murmured, as he buried her blushing face upon his bosom, ‘I did not mean to betray myself. You will think me very weak.’

‘Angel!’

‘But I could not endure to see you so unhappy.’

‘Angel!’ repeated her lover, as his arm stole around her waist, and he imprinted a kiss, the first of love he had ever given upon her yielding lips, sealing her as it were to himself, and to himself alone.

‘Kate,’ he whispered fondly, ‘you will not mar the immeasurable happiness of an hour like this by one regretful thought?’

‘I feel none,’ came a gently murmuring voice.

‘From the hour we first met I loved you,’ continued Willie, ‘although I knew not what love meant. Saw you nightly in my dreams, and felt impatient of the garish day till slumber should return, bringing the blissful vision back to my sight again. I believed you to be poor — poorer even than myself. It was for your sake I wasted the midnight oil, striving to win a name to offer you, and a fortune to protect you. Oh! how, these thoughts sustained me; hope and courage both were high within me; but when the truth was made apparent, and I saw how immeasurably you were placed above me, despair took possession of my heart, its energies died out— all but its love had faded.’

‘Dwell not on such sad fancies,’ replied the now happy girl — happy despite her tears. ‘There can be no inequality where love is mutual.’

‘Bless you, dearest, for these words,’ said her lover. ‘You know not the strength they have given me; the steady will of manhood has returned, and I will yet win a name that shall justify your choice in the eyes of your friends, your family and the world.’

‘I care not for the last,’ observed Lady Kate Kepple. ‘My choice is made; my heart is given; the faith that accompanies them can never change. We are both young, and must wait till you have finished your career at college. Should it prove successful, none will hail your triumph more truly than myself. Should it fail you,’ she added, ‘my heart and hand shall still be yours.’

With such a prospect, and an angel’s promises to cheer him, no wonder that our hero returned to Cambridge a happy man.

This edition © 2019 Furin Chime, Michael Guest

Notes, Reference and Further Reading

play propriety: An older term: ‘play the chaperone’, in a sense

Herald’s books: Records of heraldry, family pedigrees.

golden apples of the fabled garden: The myth of Tantalus, whom the gods punished by immobilizing him in the royal garden next to an enchanted apple tree, whose branches would move away each time he reached for one. Note that apples traditionally symbolize the female’s breasts, which motivates Kate’s double entendre about the apples descending.

Proteus: Note that Proteus, the Greek god of change, is also an elderly figure.

Moore, Jane. ‘Thomas Moore, Anacreon and the Romantic Tradition’. Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840 21 (2013): 30–52. Jump to pdf.

Moore, Thomas, Trans. The Odes of Anacreon, with Fifty-Four Illustrative Designs by Girodet de Roussy (1869). Jump to html version at gutenburg.org

The Works of Anacreon, Sappho, and Musaeus. Translated from the Greek by Francis Fawkes (1810)

(Includes a section on the life of Anacreon as well as several odes). Jump to free ebook (Google).

Roche, John B. The First Twenty-eight Odes of Anacreon, In Greek and in English, and in Both Languages, in Prose as Well as in Verse : with Variorum Notes a Grammatical Analysis, and a Lexicon (1827). Jump to free ebook (Google).

Hunt, Leigh. ‘Anacreon’, in Arthur Symons, ed., Essays by Leigh Hunt 1887: 169-173. Facsimile available at Internet Archive. Jump to page.