This universe grants the deceased a period of forty-nine days to cross through the boundary zone, a number that unites the tiny and the vast. The shaman – was that him? – did not want to disturb the soul’s awareness, for in this state, newly released from corporeality, swept into the perceptual and spiritual turmoil of the afterlife, it may be just as vulnerable to the perception of a benevolent spirit as it would be to a zombie or ghoul. Often, the soul does not even know it is dead. It drifts in a tenuous form, a molecule in a maelstrom.

Judgment halls materialise and dissolve. The Hall of Unfelt Regrets, for those who failed to grieve as prescribed: sorrows issued retroactively: wrong order, not transferable. Griefs spooned from repurposed billy cans. Gallery of the Unlived Life. Corridors of one’s could-have-beens: concert cellist version; loving version; not-quite-so-cruel version. “Hey you over there! No touching the dioramas,” warns one of the sullen docents. Dropping to his knees, Forbes notes that beneath the dust, there is an old rolled-out mat from a public school in Nhill, for percussion band time. Depot of Ungiven Names. Filing cabinets disappear in the smoke of raging bushfires. A clever-man with pencil and ochre offers to look up his name, charging three truths and the last sound he heard. Canteen of karmic simulacra selling one’s true desires: pies that are warm but hollow; love that tastes of copper. Waiting Room of the Second Chance That Will Not Be Offered Again. You are told your name is next, and then that it’s not. You were never meant to be here.

And on and on. The so-called guide – our Mow Fung? – surely not – regains his composure. In a flash of inspiration, he traces in the red dust the trigrams: penetrating wind above, receptive earth below, summons in his heart the image of a single willy-willy, spiralling upward. Two unbroken yang lines above, four broken yin lines beneath: making the Yi Jing hexagram Kuan, whose power lies in observing and contemplating. When the wind blows over the earth, it stirs everything up, compelling us to observe.

He envisaged the breeze sending ripples across the surface of a pool, and the soul was drawn to it. Upon that trembling mirror, a flickering image began to congeal. A voice, at first muted and reverberant, gathered itself into clarity …

• • •

“Kids’ll be real happy to see you after all this time. I reckon I’d like to see their faces, I’d get a kick out of that. I keep forgettin’ their names. What was it – Thomas you said, yer eldest? Thomas, that’s it, wasn’it? Sounds like a right little wag, that Tom, bright little bugger. I reckon I remember you saying something about him, something you said once, can’t recall now. What was it again, mate? He loves cricket, don’t he? I read up on the Australian Eleven playing over there in England, you know, how they’re doing and all that. I reckon I could tell him all about that, and learn him a few shots, like, keep a straight bat and everything.”

Forbes tilted his head. “Me uncle learned me real good, but I was better at bowlin’ than battin’ in my day, mate. I’m tall, see, like you, only a bit taller even, so I’m a good fasty, and I can spin a bit too. Here, hold on a bit, let me catch me breath and light up me pipe,” he said.

“Just bloody do it and catch up. We ain’t got all day for twaddle,” Burns said, thinking, You’ll not call my kid bugger again, you swine.

The prattle of a halfwit grates no end out here in the Christmas heat. If a man had a gun, he’d be tempted to pull it out and blow the imbecile’s head off, or else his own, just to put a stop to it, let the cicadas have their go, unspoiled by jabbering gibberish that’s meant to mean something but is, in truth, no more than babble.

The cicadas sing their soaring song beyond words; they sing of the heat, of their deaths not far off, of nothing: of an instant that deafens, and is, to them, filled with serenity and quiet.

Going by Phelan the produce merchant’s in Patrick Street, Burns stuck his head in the door and called out, “G’day Jim, back later to sort it through with ye, mate!”

Real hail-feller stuff. Could’ve been a right good salesman or a writer in one of them rags. Got the gab for it. Better still, something in the line of politics, probably. Manly grin like that, he thought, pausing to nod at his reflection, shoulders squaring, who wouldn’t vote for you? Noble – well, masculine – profile, intelligent forehead, its own mould of nobleness. He had that swaggerin’ way with him that the sheilas fall over for while other blokes can’t do nothing else but only stand by and admire. Well, he never got that far, but not through any fault of his own, and in his own way, everything he touches, he leaves his mark there. Walks into a room and they all know who’s the real man here, the stallion, all them pissing little geldings, them sheep and goats. It’s all got to do with knowing yer the number one, tougher and smarter than the next man.

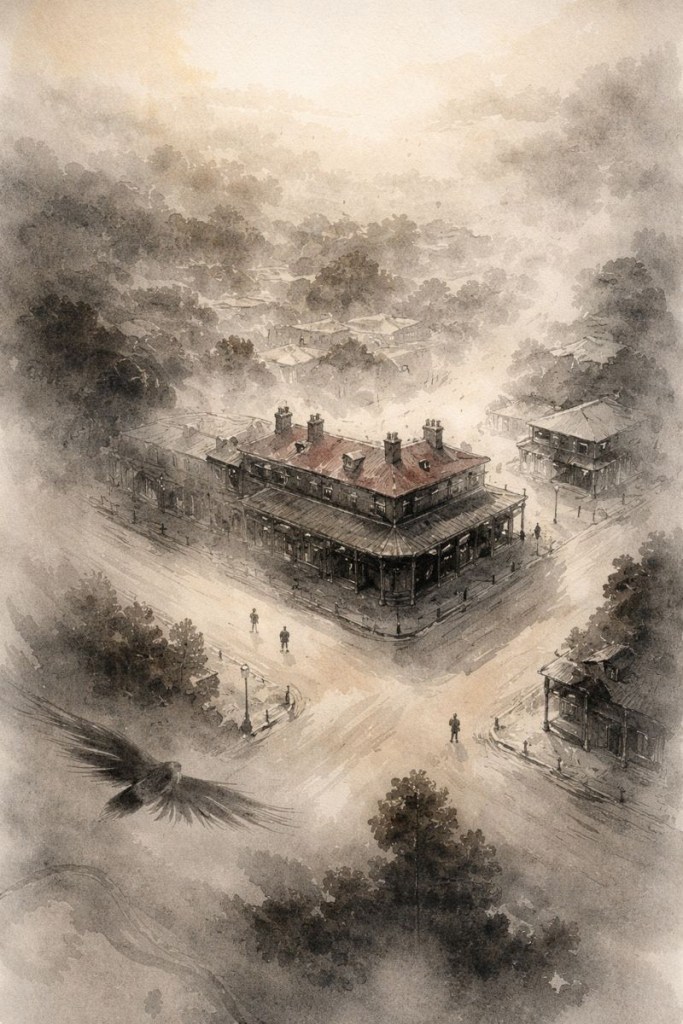

Up to the corner, and there was the pub on the main street, Fergus’s European. Across the intersection he strode, Forbes trailing in the wide, empty expanse, generous enough for a dozen willy-willies of dust and fine horse-dung. A three-dimensional cruciform emptiness rose into a vaulted silence. High above, at a faraway level past reason, a single white veil of cirrus cloud cut a lilac-tinged rupture in the pale blue surface of the sky.

He left Charley out on the front veranda blathering to Ben Wellington, a rum-looking old codger with one good eye and one sightless milky-blue, and his mate on the bench. The better to work his magic, to go in alone.

The sawdust on the pub floor had darkened to a fine grey grit. Burns scuffed it without thinking, left a faint swirl behind him.

“No, Burns, I know you.” Fergus the publican: a stout man with lambchop side-whiskers, brawny arms under rolled-up sleeves. Choleric, a real Admiral of the Red. The pressure of his blood thrust forth the veins and squeezed beads of perspiration from the pores of his fleshy red phizog.

“Oh, come on, George, do a cove a favour for once. Just for a night or two. I always give you what I owed you, y’know that.”

“That’ll be the day. Look, where is he, anyway?”

“Just out the front, jawing with some old bastards. You should be paying him to stay here to babysit ’em. They thrive on that rot he goes on with. Good entertainment for ’em. Works out well for everyone around, you and all. Pulling his leg keeps them from fightin’ and breakin’ your place up.”

“Look here, I don’t mind if they all get the hell out altogether. More strife than they’re worth.”

“Do us a favour, mate, for old times. What about that trench I dug you the other month?”

“Other year. You know full well I’ve paid you back ten times over. Favours. What rot. Well, where’d he stay last night, anyhow?”

“Hunter’s Ball and Mouth.”

Forbes wandered in with a “G’day squire,” and stood grinning at Fergus over the bar.

“Jeez, ’at one-eyed feller out there knows about the nags. Blue-eyed Dick in the fourth, he reckons.” Chortled madly for who knows why? – unwritten prerogative of a simple mind.

“Why doesn’t he stay there again, then?”

“Truth is, I want to get him off the grog. I brought him here for the purpose of having him sober.”

“What are you going to do?”

“We are going to Dunkeld to dig some dams.”

“Bloody Carter Brothers,” Forbes said. “Got three running in the Horsham Cup next week. Lion, Silvis or sompthin, and – what the hell was it? Rosebunch or summit, shit –” He slouched back to the front door. “Was that Rosebunch, Mr. Wellington, was it? Oh, my stars, that’s right. An’ who was that one you tipped me for the Cup? Ah, that’s it, that’s the one!”

Slouched back to the bar.

“What are you standing there looking at us like a putty-brain for, yer great galoot? Here, give us a couple of mugs of yer best tangle-foot, thanks mate.”

Fergus looked at Burns, who shrugged and coughed up two deaners, which rang light on the bar and came to rest together with a clink. Fergus poured out three pots of ale and listened impassively to Burns’s account of their affairs. They would have gone today but were waiting for a watch to come down from Glenorchy, which was being kept for a debt they owed. They sent a telegram yesterday to release it.

“Rosebud it was,” Forbes said, wiping the moisture from his top lip onto the back of his hand. “Rosebud, that Carters’ nag, but he reckons put a quid on Lady Emily. Lady Emily for the Cup by two lengths, he reckons. Four-year-old. Five? No, four it was, he said. I believe I’ll catch the train up there next week and have a quid or two on her.”

Burns turned back to Fergus.

“We got money and more to come. We have ordered thirty quid worth of goods from Mister Phelan and are waiting for them to take them to the station. Else we’d have already gone. Now, I’m at home for a few more days with the missus and kids, and I want him –” sideways thumb at Forbes – “to stay here where I can keep an eye on him.”

“Yeah, but remember,” Forbes reminded his mate, “I have to come down and meet the missus and young Tom and play cricket and all that.”

Poor bloody woman, Fergus thought. Burns kept quiet about the appointment, praying it might go away.

“So I only need a cheque for thirty quid to pay Phelan, temporary like, I’ll get it back to you in no time flat. I just sold a farm for six-hundred quid, and we’re off to acquire another.”

“There’s land open for selection between Stawell and Glenorchy, didn’t you even know that?” Forbes stared at Phelan, incredulous.

“There’s an idea!” Burns said. “We take enough for ourselves and leave a portion for you.”

“Beauty!” Forbes said. “Not bad interest on a thirty quid loan, eh?”

A low animal urge stirred in Burns’s gut and surfaced as a long, lascivious moan.

“Real fetchin’, Eliza,” he said. “Looking real fetchin’ today.”

The young woman behind the bar with a tray full of glasses for the sink, flashed a smile and slipped past behind her father.

“Gotta love them freckled bushfire blondes, George. Lost the baby fat, though. Don’t work her too hard, mate.”

Fergus, fidgeting, took a gulp.

“If her husband hears you, you’ll be laughing on the other side of your face.”

Ben Wellington limped in and sat down further up the bar. Forbes sidled over – “You don’t want to be a Jimmy Woodser, mate, up north that’s what they call a chap what breasts a public bar and tips the finger alone” – and got him started again on the horses.

“Vandermoulin and Tallyho the four-year-olds didn’t do no good at Ararat, but McSweeney’s five-year-old Too Late, he’ll be a goer in the handicap hurdles. Paul McGidden has been training him over at Longerenong Pastoral Run. Bloody good trainer, had a runner in the Melbourne Cup, couple years back.”

“What about Blue-eyed Dick, Mister Wellington, what you reckon there?”

“I reckon I ain’t heard of him.”

“You know, Blue-eyed Dick out of Little Nell and Off His Kadoova, you know.”

“No, I reckon I ain’t heard of ’im, not around the Wimmera I ain’t.”

• • •

“Life is strange,” mused he who was once called Mow Fung – the not-shaman. Not easy to hold onto your identity in hell. “We live it forwards but understand it backwards. To develop through the gua, Kuan needs alert observation with clarity. You must restore the eternal while residing in the temporal, both of which move in opposite directions. You must observe closely, in order to tell the real from the false. Hold on to the real and get rid of the false. It is like the shrine ritual. First you wash the dust off your hands, before you make your offering. You have a little shrine made of dust.”

Dust enveloped the wandering shade, who withdrew into a groan, but as though anticipating a truth in what was to come, forced its awareness back into the play of shadow puppets before them.

• • •

Burns rented the place from Phelan the merchant, for whose business his wife took on laundry and sewing. It was a fair-sized block along from the police station, with a parched backyard, tired dwelling, and fence nigh on splintering to ruins; most of its palings were askew or off their rails.

Forbes arrived mid-morning and introduced himself to Florence, who told him Burns had gone down the street to fix up some business or other with Phelan the merchant. Burns had mentioned nothing to her about Forbes, but she absorbed his sudden existence with the same anaesthetised calm that filtered the world for her, a symptom of a weariness deeper than the heavy years he’d burdened her with. Once, she’d indulged his fancies of a grand future shaped by his quality and wisdom, and once she used to pine for his return, until even that became a sham and vanished not long after the last echoes of his pretended love fell silent.

The children grew accustomed to his increasingly lengthy absences, but continued to anticipate his returns. He was always going to bring them a present next time, and they learned to believe there was commitment beneath the promise, initially. They were not lies exactly, but a seductive flicker – something like love or care – that expires without sufficient fuel. They would whisper and giggle to each other in their beds at the bedspring squeaks and concupiscent slurps that ornamented the darkness after he showed up, until soon it would be still again, as usual.

Forbes made himself useful picking up the abundant dog droppings with the short-handled shovel, disposing of them near the coal heap in the back corner away from the shed, where she told him. The dog was off with the kids and their mates, down to the creek to swim and pick blackberries. She sat darning on the veranda, watching the visitor. When the wind blows over the earth, it stirs everything up, compelling us to observe. Some took her for slow, because of how she never rushed to reply, on the occasions she deigned to. Her needle moved as though with a will of its own; her gaze was like a still pool. Ah, a receptive surface.

She still had her, the tiny wooden thing. The Dew Doll. She sensed that, tucked away in the dresser, nestled under old muslin and petticoat lace, among the few precious things she kept, the doll had stirred – as it did only once in a blue moon. It came back to her now, from years ago, the one time she’d wandered over to Deep Lead. The man who ran the curious shop in the Chinese camp had given it to her laughing, when she showed an interest, stroking it, for some reason not wanting to let it go. He couldn’t tell her much, only that it was old. Later the doll started to put ideas straight into her head, and she knew they were right. Things she should do, or say, or leave unsaid. What would go missing. Who to beware. The slip stuck to the back with mulberry paste bore the date some poor baby had died. Between the coiled silk buns of its hair, there was a hole with paper pushed deep inside, which the doll said she shouldn’t try to take out. The doll knew when the dew was going to gather – a rare thing in this country – and would let Florence know, so she could carry her out beside the shed, to feed on it. She’d wake up knowing. The doll had stirred. There’d be dew.

Forbes found a tin of rusty nails in the shed and set out to mend the fence, a task that drew more curses from him than it would from an average man. After each outburst, he’d flash her a wide, bashful grin and a demonstrative shrug. She’d nod back to him with her tranquil, closed-mouth smile. She was struck by the thought: There is something odd about this childish, well-meaning man. I know! He does not realize he is already dead. But there are others close by who do.

He liked her drawl and what he took to be her patient attitude, which tended to suppress his frantic exuberance and draw out his contemplative side. When he finished, by a miracle the fence was still standing, and he joined her on the veranda, sitting on the step near her feet in the dog’s spot. Imagining she had an interest in his history with her husband, or more accurate to say, play-acting that she had, he traced through an idealised version of their shared narrative over the past months, since they’d started working together on the line at Naracoorte, on the South Australian border, where he’d stayed at Bridget Enright’s boarding house. Seven bob a week, he got.

“A well and respected place it was, no drink of any sort sold, not like them what the bloody shanty-keepers run, which sells the vilest, horrible adulterations of all kinds, hideous compounds, they are, made only of chemicals, some sort of blend which costs about sixpence. Full of navvies, mostly slopers only there for a skinful – that’s blokes who’ll get fleeced and then decamp without fulfilling their dues, like. Mugs game to take a hiding and then pay for it, of course.”

Better be careful what he says there, Bridget took a bit of a shine to Burnsie. Of course, when he detoured, Florence immediately knew the truth, but nothing could have been of less significance to her, it had all been sour for so long. Pretty, pretty doll …

Then they’d headed back over this way to Dimboola. He told her about his mates the Painter brothers and Johnson. Burnsie’s – Robert’s – mates too, of course, though he had a bit of a run-in once or twice with the older one. Told her about his old sweetheart Hessie Hesslitt, who lives over at Mandurang now, but last saw her four or five years ago at Hamilton. As nice as could be, but ran off with some slicker, of course. Florence only tutted, nodded and made gentle wordless sounds as she worked, which warmed the pit of Forbes’s stomach, though there was no such intention.

He was afflicted by a loss of words, so he took a folded-up newspaper page from his pocket, with the aim of entertaining her further.

“Robert helps me with these sometimes – explains, you know, helps me read. You get some real informative stuff out of them. This one’s what’s called ‘Answers to Correspondents’ – that’s these jokers who send in questions for things they don’t know about, see …”

She made one of her pleasant sounds, high-pitched and undulating, but smooth-like, to show she was interested.

“… so you pick up a lot of good stuff. Take this, for instance, I’ve already read it once or twice, it’s from someone calls ’emself Cornstalk – they’ve got all sorts of names: In writing to the Queen, what form do you use, and to where do you address your letter? What do you reckon, Florence? Well, here’s the answer. We presume you want to write a petition. The form is ‘To Her Most Gracious Majesty Queen Victoria, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, Empress of Indias: May it please your Majesty,’ and end, ‘And your petitioner will ever pray.’ Address through the Secretary of State for the Colonies.’ I reckon the Queen’ll be hearing from old Cornstalk before long, eh?”

A placid smile on Florence’s face, shaking her head tutting, her eyes cast down on her darning. Pretty, pretty …

“Here you go. Kiara asks the distance from Echuca to Sydney, and the cheapest route, and the cost. Answer: The cheapest route is via Melbourne. Train fare, seventeen shillings; steamer, thirty shillings to Sydney – Shit! – Distance overland, five hundred and forty miles. Echuca … That’d be, um, up there near bloody er –”

A cattle dog mix heralded the arrival of four of Florence’s offspring, trotting around the corner to greet the woman and sniff at the man, before inspecting changes to its scent-map of the backyard and urinating at the door of the shed. The three boys and a girl stared at Forbes dumbly, and he similarly back, turning suddenly shy. Hearing one referred to as ‘Tom,’ he summoned some bravado and forced a grin.

“G’day young’un. I know all about you from yer old man, mate. Bloody good little cricketer he said you was, tyke,” but the boy drew himself up and stared wordlessly back, before spitting on the ground and strutting after his siblings into the house.

“Rough nut, eh?” Forbes mumbled, but Florence was bent away from him, gathering up her work.

Forbes was smoking his pipe in the falling light when Burns showed up with Phelan and a gallon of brandy, which Phelan had sold Burns and been invited to come along and help drink it. The three set to and lasted into the small hours.

“Rotten coppers down the street got it in for me,” said Burns towards the end, “so I snapped a couple of their saplings they were trying to grow out the front. Here’s what I’m gunna do, Flo heard it from a Chinese witchdoctor. You go to the cemetery and scrape up a handful of dirt next to a grave. Then you take that and spread it in front of someone’s door, where they won’t see it, so they tramp it all through the house. Brings them real bad luck that won’t never go away unless you get a witchdoctor to come and fix it up.”

• • •

The not-shaman says, “We must watch closely. Sometimes, the last thought a person has before dying, if it is a strong, clear, and pure one, will open up an aperture from this dark place, through which he may escape this suffering and chaos by going straight into the spirit world. If not … well, we will just have to wait and see and do our best.“

He detected a resigned sigh, interpreting it as a constructive sign.

• • •

About noon the next day, humping their swags and thirty quid worth of supplies, the two men left to make their selection of the land off the old Glenorchy Road and then head for Dunkeld to do the dam. The kids had taken off at sparrow’s twit somewhere with the dog. Florence had watched Burns go to fetch Forbes from the pub that morning, then turned back to go through the stuff Phelan brought her.

“Fergus ain’t here, we must wait and give him his twenty-seven bob for the room,” Forbes said.

“Too right,” Burns said. “No, we’ll just slope, do the disappearing trick. He’s a mug, old George – ripe for rolling over.”

“Do the old Jerry Diddler, eh? I’m up for it, mate.”

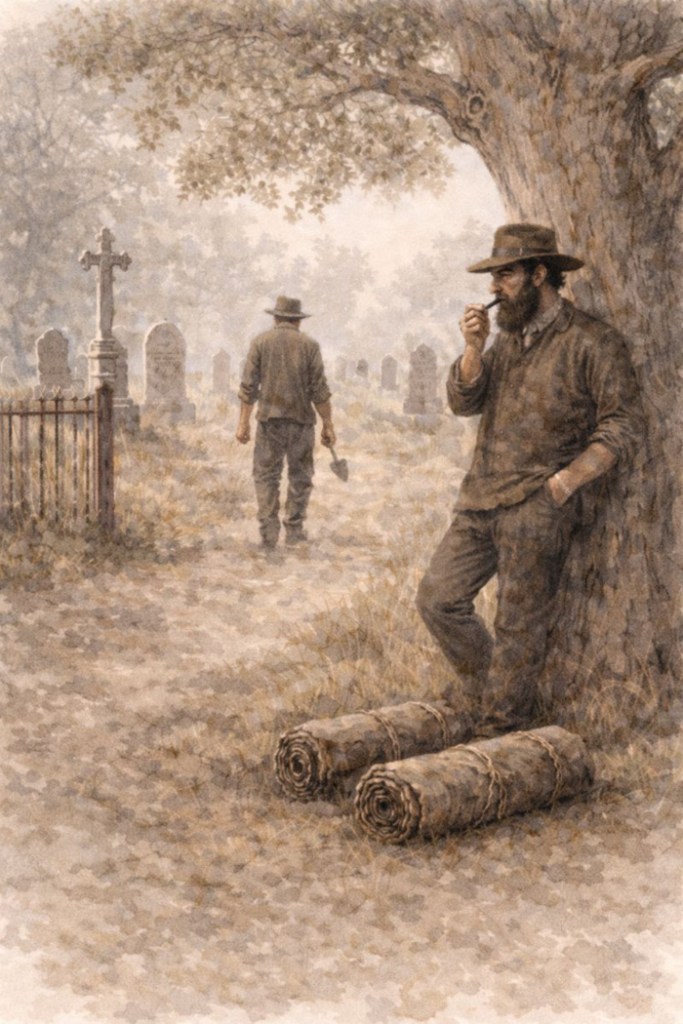

They skirted Main Street and went along Cemetery Road. Burns thought he may as well duck into the cemetery reserve to take care of his little errand, while Forbes stood cockatoo out front under a tree, smoking his pipe. The shadows cast by the headstones were short and sharp in the sun, like a grinful of broken teeth. When he came out, Burns patted his trouser pocket and nodded at Forbes.

Who should they see fifty yards away, down Mary Street, but George bloody Fergus; he only chucked them a wave, as they turned back into Main Street. Burns had his sly piece of business to see to at the police barracks – in and out. Then they made for the old Glenorchy Road cutting a shortcut through some timbered bushland and struck out for Deep Lead.

Burns, in no mood for conversation, tolerated Forbes’s whistling, fatuous comments, and laughter inspired by the few birds who had braved the heat to fly or call out. Some Headache Birds had lobbed in to mate and sang out heedless of the two.

Sleep Didi, sleep. Sleep Didi, sleep. Sleep Didi, sleep, one carried on monotonously.

Forbes laughed carelessly.

“Sleep maybe!” he called back in imitation as they tramped. Burns bent over to do up the lace on his boot, then hung back as they went along.

A flock of Sulphur-crested Cockatoos burst through the dry grey-green treetops in front of them. Raucous, chattering screeches, sharp squawks and whistles, then quieter murmurings as they settled on their branches.

Abruptly, a lone, hidden Jacky Winter said his piece, as he watched the two turn down a track towards the Four Post Diggings in ironbark country.

Plicky-plicky-plicky … Plicky-plicky-plicky …

“Peter, Peter, Peter!” Forbes called, to be answered by the pretty, lilting ditty of a Scarlet Robin –

Wee-cheedallee-dalee – then quiet, then tick, tick, tick, and a rapid burst of scolding chatter.

From the draft novel Stawell Bardo © Michael Guest 2025