The final tale in this series is about what Frenchmen are often believed to be most obsessed with: L’Amour. It might be all too easy to be cynical about any such tale written in the words of another time, but France still engages us, despite the subject. Oh, please don’t get me wrong. Flowery expressions of passion or woe might not be to my taste, but I do have some empathy for those unhappy in love, having been there myself and survived. The emptiness and obsession of it, all wonderfully described by France.

Forgive my indulgence in this final of the tales, but I’m reminded of a German poem by Erich Fried, which I’ll translate for you:

It's silly, says reason It is what it is, says love It's misfortune, says calculation It's nothing but pain, says fear It's hopeless, says insight It is what is, says love It's ridiculous, says pride It"s foolish, says caution It's impossible, says experience It is what it is, says love

At first, the title of our story, ‘Mademoiselle Roxane’, reminded me of perhaps not quite what the author would have intended. A movie poster with the same female name and some Hollywood comedy actor named Steve with a ridiculously exaggerated Cyrano De Bergerac nose. Yet I guess that this too was a film about unrequited love, albeit a supposedly funny one about some modern day guy like Cyrano.

So what would have happened, if during some Paris night long ago, our heroes had encountered such a young man, and not a beautiful young woman in the same situation? Most probably, there would not have been a whisker or even a nose of a tale. But a brilliant author has the artistic schnozzle to get all the elements right to please his readers, and so, enter stage left, beautiful Mademoiselle Sophie. My strange mind correlates too much of the lovelorn gooey sort of stuff with that awful signature tune which comedian Jack Benny used to play on his violin, “Love in Bloom”. I used to think of adapted lyrics that I had imagined went, “When our cardboard box got wet, so did all the cigarettes, and the weed…”—to at least internally mock overdone hard luck stories when I was subjected to them.

So yes, prepare yourself for a bit of a hard luck story. But also for an ending worthy of Anatole France. A happy one? I’ll have to leave you in suspense. I’ll miss reading his Merrie Tales ofJacques Tournebroch. I’m sure you will too.

Mademoiselle Roxane

![image852SPECKLE[FINAL]](https://furinchime.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/image852specklefinal.jpg)

Y good master, M. l’Abbé Coignard, had taken me with him to sup with one of his old fellow-students, who lodged in a garret in the Rue Gît-le-Cour. Our host, a Premonstratensian Father of much learning and a fine Theologian, had fallen out with the Prior of his House for having writ a little book relating the calamities of Mam’zelle Fanchon. The end of it was he turned tavern-keeper at The Hague. He was now returned to France and living precariously by the sermons he composed, which were full of high argument and eloquence. After supper he had read us these same calamities of Mam’zelle Fanchon, source of his own, and the reading had kept us there till a late hour. At last I found myself without-doors with my good master, under a wondrous fine summer’s night, which made me straightway comprehend the verity of the ancient fables regarding the loves of Diana and feel how natural it is to employ in soft dalliance the silent, silvery hours of night. I said as much to M. l’Abbé Coignard, who retorted that love is to blame for many and great ills.

“Tournebroche, my son,” he asked me, “have you not just heard from the mouth of yonder good Monk how, for having loved a recruiting sergeant, a clerk of M. Gaulot’s mercer at the sign of the Truie-qui-file, and the younger son of M. le Lieutenant-Criminel Leblanc, Mam’zelle Fanchon was clapped in hospital? Would you wish to be any of these,—sergeant or clerk or limb of the law?”

I answered I would indeed. My good master thanked me for my candid avowal, and quoted some verses of Lucretius to persuade me that love is contrary to the tranquillity of a truly philosophical soul.

Thus discoursing, we were come to the round-point of the Pont-Neuf. Leaning our elbows on the parapet, we looked over at the great tower of the Châtelet, which stood out black in the moonlight.

“There might be much to say,” sighed my good master, “on this justice of the civilized nations, the punishments whereof in retaliation are often more cruel than the crime itself I cannot believe that these tortures and penalties that men inflict on their fellows are necessary for the safeguarding of States, seeing how from time to time one and another legal cruelty is done away with without hurt to the commonweal. And I hold it likely that the severities they still maintain are no whit more useful than those they have abolished. But men are cruel. Come away, Tournebroche, my dear lad; it grieves me to think how unhappy prisoners are even now lying awake behind those walls in anguish and despair. I know they have done faultily, but this doth not hinder me from pitying them. Which of us is without offence?”

We went on our way. The bridge was deserted save for a beggarman and woman, who met on the causeway. The pair drew stealthily into one of the recesses over the piers, where they lurked together on the door-step of a hucksters booth. They seemed well enough content, both of them, to mingle their joint wretchedness, and when we went by were thinking of quite other things than craving our charity. Nevertheless my good master, who was the most compassionate of men, threw them a half farthing, the last piece of money left in his breeches pocket.

“They will pick up our obol,” he said, “when they have come back to the consciousness of their misery. I pray they may not quarrel then over fiercely for possession of the coin.”

We passed on without further rencounter till on the Quai des Oiseleurs we espied a young damsel striding along with a notable air of resolution. Hastening our pace to get a nearer view, we saw she had a slim waist and fair hair in which the moonbeams played prettily. She was dressed like a citizen’s wife or daughter.

“There goes a pretty girl,” said the Abbé; “how comes it she is out of doors alone at this hour of night?”

“Truly,” I agreed, “’tis not the sort one generally encounters on the bridges after curfew.”

Our surprise was changed to alarm when we saw her go down to the river bank by a little stairway the sailors use. We ran towards her; but she did not seem to hear us. She halted at the edge; the stream was running high, and the dull roar of the swollen waters could be heard some way off. She stood a moment motionless, her head thrown back and arms hanging, in an attitude of despair. Then, bending her graceful neck, she put her two hands over her face and kept it hid behind her fingers for some seconds. Next moment she suddenly grasped her skirts and dragged them forward with the gesture a woman always uses when she is going to jump. My good master and I came up with her just as she was taking the fatal leap, and we hauled her forcibly backward. She struggled to get free of our arms; and as the bank was all slimy and slippery with ooze deposited by the receding waters (for the river was already beginning to fall), M. l’Abbé Coignard came very near being dragged in too. I was losing my foothold myself. But as luck would have it, my feet lighted on a root which held me up as I crouched there with my arms round the best of masters and this despairing young thing. Presently, coming to the end of her strength and courage, she fell back on M. l’Abbé Coignard’s breast, and we managed all three to scramble to the top of the bank again. He helped her up daintily, with a certain easy grace that was always his. Then he led the way to a great beech-tree at the foot of which was a wooden bench, on which he seated her.

Taking his place beside her:

“Mademoiselle,” he said gently, “you need have no fear. Say nothing just yet, but be assured it is a friend sits by you.”

Next, turning to me, my master went on:

“Tournebroche, my son, we may congratulate ourselves on having brought this strange adventure to a good end. But I have left my hat down yonder on the river bank; albeit it has lost pretty near all its lace and is thread-bare with long service, it was still good to guard my old head, sorely tried by years and labours, against sun and rain. Go see, my son, if it may still be found where I dropped it. And if you discover it, bring it me, I beg,—likewise one of my shoe buckles, which I see I have lost. For my part I will stay by this damsel we have rescued and watch over her slumber.”

I ran back to the spot we had just quitted and was lucky enough to find my good master’s hat. The buckle I could not espy anywhere. True, I did not take any very excessive pains to hunt for it, having never all my life seen my good master with more than one shoe buckle. When I returned to the tree, I found the damsel still in the same state, sitting quite motionless with her head leant against the trunk of the beech. I noticed now that she was of a very perfect beauty. She wore a silk mantle trimmed with lace, very neat and proper, and on her feet light shoes, the buckles of which caught the moonbeams.

I could not have enough of examining her. Suddenly she opened her drooping lids, and casting a look that was still misty at M. Coignard and me, she began in a feeble voice, but with the tone and accent, I thought, of a person of gentility:

“I am not ungrateful, sirs, for the service you have done me from feelings of humanity; but I cannot truthfully tell you I am glad, for the life to which you have restored me is a curse, a hateful, cruel torment.”

At these sad words my good master, whose face wore a look of compassion, smiled softly, for he could not really think life was to be for ever hateful to so young and pretty a creature.

“My child,” he told her, “things strike us in a totally different light according as they are near at hand or far off. It is no time for you to despair. Such as I am, and brought to this sorry plight by the buffets of time and fortune, I yet make shift to endure a life wherein my pleasures are to translate Greek and dine sometimes with sundry very worthy friends. Look at me, mademoiselle, and say,—would you consent to live in the same conditions as I?”

She looked him over; her eyes almost laughed, and she shook her head. Then, resuming her melancholy and mournfulness, she faltered:

“There is not in all the world so unhappy a being as I am.”

“Mademoiselle,” returned my good master, “I am discreet both by calling and temperament; I will not seek to force your confidence. But your looks betray you; any one can see you are sick of disappointed love. Well, ’t is not an incurable complaint. I have had it myself, and I have lived many a long year since then.”

He took her hand, gave her a thousand tokens of his sympathy, and went on in these terms:

“There is only one thing I regret for the moment,—that I cannot offer you a refuge for the night, or what is left of it. My present lodging is in an old château a long way from here, where I am busy translating a Greek book along with young Master Tournebroche whom you see here.”

My master spoke the truth. We were living at the time with M. d’Astarac, at the Château des Sablons, in the village of Neuilly, and were in the pay of a great alchemist, who died later under tragic circumstances.

“At the same time, mademoiselle,” my master added, “if you should know of any place where you think you could go, I shall be happy to escort you thither.”

To which the girl answered she appreciated all his kindness, that she lived with a kinswoman, to whose house she could count on being admitted at any hour; but that she had rather not return before daylight. She was fain, she said, not to disturb quiet folks’ sleep, and dreaded moreover to have her grief too painfully renewed by the sight of her old, familiar surroundings.

As she spoke thus, the tears rained down from her eyes. My good master bade her:

“Mademoiselle, give me your handkerchief, if you please, and I will wipe your eyes. Then I will take you to wait for daybreak under the archways of the Halles, where we can sit in comfort under shelter from the night dews.”

The girl smiled through her tears.

“I do not like,” she said, “to give you so much trouble. Go your way, sir, and rest assured you take my best thanks with you.”

For all that she laid her hand on the arm my good master offered her, and we set out, all the three of us, for the Halles. The night had turned much cooler. In the sky, which was beginning to assume a milky hue, the stars were growing paler and fainter. We could hear the first of the market-gardeners’ carts rumbling along to the Halles, drawn by a slow-stepping horse, half asleep in the shafts. Arrived at the archways, we chose a place in the recess of a porch distinguished by an image of St. Nicholas, and established ourselves all three on a stone step, on which M. l’Abbé Coignard took the precaution of spreading his cloak before he let his young charge sit down.

Thereupon my good master fell to discoursing on divers subjects, choosing merry and enlivening themes of set purpose to drive away the gloomy thoughts that might assail our companion’s mind. He told her he accounted this rencounter the most fortunate he had ever chanced on all his life, and that he should ever cherish a fond recollection of one who had so deeply touched him,—all this, however, without ever asking to know her name and story.

My good master thought no doubt that the unknown would presently tell him what he refrained from asking. She broke into a fresh flood of weeping, heaved a deep sigh and said:

“I should be churlish, sir, to reward your kindness with silence. I am not afraid to trust myself in your hands. My name is Sophie T———. You have guessed the truth; ’tis the betrayal of a lover I was too fondly attached to has brought me to despair. If you deem my grief excessive, that is because you do not know how great was my assurance, how blind my infatuation, and you cannot realize how enchanting was the paradise I have lost.”

Then, raising her lovely eyes to our faces, she went on:

“Sirs, I am not such a woman as your meeting me thus at night time might lead you to suppose. My father was a merchant. He went, in the way of trade, to America, and was lost on his way home in a shipwreck, he and his merchandise with him. My mother was so overwhelmed by these calamities that she fell into a decline and died, leaving me, while still a child, to the charge of an aunt, who brought me up. I was a good girl till the hour I met the man whose love was to afford me indescribable delights, ending in the despair wherein you now see me plunged.”

So saying, Sophie hid her face in her handkerchief. Presently she resumed with a sigh:

“His worldly rank was so far above my own I could never expect to be his except in secret. I flattered myself he would be faithful to me. He swore he loved me, and easily overcame my scruples. My aunt was aware of our feelings for one another, and raised no obstacles, for two reasons,—because her affection for me made her indulgent, and because my dear lover’s high position impressed her imagination. I lived a year of perfect happiness only equalled by the wretchedness I now endure. This morning he came to see me at my aunt’s, with whom I live. I was haunted by dark forebodings. As I dressed my hair but an hour or so before, I had broken a mirror he had given me. The sight of him only increased my misgivings, for I noticed instantly that his face wore an unaccustomed look of constraint… Oh! sir, was ever woman so unhappy as I?…”

Her eyes filled again with tears; but she kept them back under her lids, and was able to finish her tale, which my good master deemed as touching, but by no means so unique, as she did herself.

“He informed me coldly, though not without signs of embarrassment, that his father having bought him a Company, he was leaving to join the colours. First, however, he said, his family required him to plight his troth to the daughter of an Intendant of Finances; the connection was advantageous to his fortune and would bring him means adequate to support his rank and make a figure in the world. And the traitor, never deigning to notice my pale looks, added in his soft, caressing voice which had made me so many vows of affection, that his new obligations would prevent his seeing me again, at least for some while. He assured me further that he was still my friend and begged me to accept a sum of money in memory of the days we had passed together.

“And with the words he held out a purse to me.

“I am telling you the truth, sirs, when I assure you I had always refused to listen to the offers he repeated again and again, to give me fine clothes, furniture, plate, an establishment, and to take me away from my aunt’s, where I lived in very narrow circumstances, and settle me in a most elegant little mansion he had in the Rue di Roule. My wish was that we should be united only by the ties of affection, and I was proud to have of his gift nothing but a few jewels whose sole value came from the fact of his being the donor. My gorge rose at the sight of the purse he offered me, and the insult gave me strength to banish from my presence the impostor whom in one moment I had learnt to know and to despise. He faced my angry looks unabashed, and assured me with the utmost unconcern that I could know nothing of the paramount obligations that fill the existence of a man of quality, adding that he hoped eventually, when I looked at things quietly, I should come to see his behaviour in a better light. Then, returning the purse to his pocket, he declared he would readily find a way of putting the contents at my disposal in such a manner as to make it impossible for me to refuse his liberality. Thus leaving me with the odious, the intolerable implication that he was going to make full amends by these sordid means, he made for the door to which I pointed without a word. When he was gone, I felt a calmness of mind that surprised myself. It arose from the resolution I had formed to die. I dressed with some care, wrote a letter to my aunt asking her forgiveness for the pain I was about to cause her by my death, and went out into the streets. There I roamed about all the afternoon and evening and a part of the night, moving from busy thoroughfare to deserted lane without a trace of fatigue, postponing the execution of my purpose to make it more sure and certain under the favouring conditions of darkness and solitude. Possibly too I found a certain weak pleasure in dallying with the thought of dying and tasting the mournful satisfaction of my coming release from my troubles. At two o’clock in the morning, I went down to the river’s brink. Sirs, you know the rest,—you snatched me from a watery grave. I thank you for your goodness,—though I am sorry you saved my life. The world is full of forsaken women. I did not wish to add another to the number.”

Sophie then fell silent and began weeping afresh. My good master took her hand with the greatest delicacy.

“My child,” he said, “I have listened with a tender interest to the story of your life, and I own ‘tis a sad tale. But I am happy to discern that your case is curable. Not only was your lover unworthy of the favours you showed him and has proved himself on trial a selfish, cruel-hearted libertine, but I see plainly your love for him was only an impulse of the senses and the effect of your own sensibility, the particular object of which mattered far less than you imagine. What there was rare and excellent in the liaison came from you. Well then, nothing is lost, since the source still remains. Your eyes, which have thrown a glamour of the fairest hues over, I doubt not, a very ordinary individual, will not cease to go on shedding abroad elsewhere the same bright rays of charming self-delusion.”

My good master said more in the same strain, dropping from his lips the finest words ever heard anent the tribulations of the senses and the errors lovers are prone to. But, as he talked on, Sophie, who for some while had let her pretty head droop on the shoulder of this best of men, fell softly asleep. When M. l’Abbé Coignard saw his young friend was wrapped in a sound slumber, he congratulated himself on having discoursed in a vein so meet to afford repose and peace to a suffering soul.

“It must be allowed,” he chuckled, “my sermons have a beneficent effect.”

Not to disturb Mademoiselle’s slumbers, he took a thousand pretty precautions, amongst others constraining himself to talk on uninterruptedly, not unreasonably apprehensive that a sudden silence might awake her.

“Tournebroche, my son,” he said, turning to me, “look, all her sorrows are vanished away with the consciousness she had of them. You must see they were all of the imagination and resided in her own thought. You must understand likewise they sprang from a certain pride and overweening conceit that goes along with love and makes it very exacting. For, in truth, if only we loved in humbleness of spirit and forgetfulness of self, or merely with a simple heart, we should be content with what is vouchsafed us and should not straightway cry treason when some slight is put on us. And if some power of loving were left us still, after our lover had deserted us, we should await the issue in calmness of mind to make what use of it God should please to grant.”

But the day was just breaking by this time, and the song of the birds grew so loud it drowned my good master’s voice. He made no complaint on this score.

“Hearken,” he said, “to the sparrows. They make love more wisely than men do.”

Sophie awoke in the white light of dawn, and I admired her lovely eyes, which fatigue and grief had ringed with a delicate pearly-grey. She seemed somewhat reconciled to life, and did not refuse a cup of chocolate which my good master made her drink at Mathurine’s door, the pretty chocolate-seller of the Halles.

But as the poor child came into more complete possession of her wits, she began to trouble about sundry practical difficulties she had not thought of till then.

“What will my aunt say? And whatever can I tell her?” she asked distractedly.

The aunt lived just opposite Saint-Eustache, less than a hundred yards from Mathurine’s archway. Thither we escorted her niece; and M. l’Abbé Coignard, who had quite a venerable look, though one shoe was unbuckled, accompanied the fair Sophie to the door of her aunt’s lodging and pitched that lady a fine tale:

“I had the happy fortune,” he informed her, “to encounter your good niece at the very moment when she was assailed by four footpads armed with pistols, and I shouted for the watch so lustily that the thieves took to their heels in a panic. But they were not quick enough to escape the sergeants who, by the rarest chance, ran up in answer to my outcries. They arrested the villains after a desperate tussle. I took my share of the rough and tumble, and I thought at first I had lost my hat in the fray. When all was over, we were all taken, your niece, the four footpads and myself, before his Honour the Lieutenant-Criminel, who treated us with much consideration and detained us till daylight in his cabinet, taking down our evidence.” The aunt answered drily:

“I thank you, sir, for having saved my niece from a peril which, to say the truth, is not the risk a girl of her age need fear the most, when she is out alone at night in the streets of Paris.”

My good master made no answer to this; but Mademoiselle Sophie spoke up and said in a voice of deep feeling:

“I do assure you, Aunt, Monsieur l’Abbé saved my life.”

* * *

Some years after this singular adventure, my master made the fatal journey to Lyons from which he never returned. He was foully murdered, and I had the ineffable grief of seeing him expire in my arms. The incidents of his death have no connexion with the matter I speak of here. I have taken pains to record them elsewhere; they are indeed memorable, and will never, I think, be forgotten. I may add that this journey was in all ways unfortunate, for after losing the best of masters on the road, I was likewise forsaken by a mistress who loved me, but did not love me alone, and whose loss nearly broke my heart, coming after that of my good master. It is a mistake to suppose that a man who has received one cruel blow grows callous to succeeding strokes of calamity. Far otherwise; he suffers agonies from the smallest contrarieties. I returned to Paris in a state of dejection almost beyond belief.

Well, one evening, by way of enlivening my spirits, I went to the Comédie, where they were playing Bajazet, one of Racine’s excellent pieces. I was particularly struck by the charm and beauty, no less than the originality and talent, of the actress who took the part of Roxane. She expressed with a delightful naturalness the passion animating that character, and I shuddered as I heard her declaim in accents that were harmonious and yet terrible the line:

Écoutez Bajazet, je sens que je vous aime (“Hearken, Bajazet, I feel I love you”)

I never wearied of gazing at her all the time she occupied the stage, and admiring the beauty of her eyes that gleamed below a brow as pure as marble and crowned by powdered locks all spangled with pearls. Her slender waist too, which her hoop showed off to perfection, did not fail to make a vivid impression on my heart. I had the better leisure to scrutinize these adorable charms as she happened to face in my direction to deliver several important portions of her rôle. And the more I looked, the more I felt convinced I had seen her before, though I found it impossible to recall anything connected with our previous meeting. My neighbour in the theatre, who was a constant frequenter of the Comédie, told me the beautiful actress was Mademoiselle B———, the idol of the pit. He added that she was as great a favourite in society as on the boards, that M. le Duc de La ——— had made her the fashion and that she was on the highroad to eclipse Mademoiselle Lecouvreur.

I was just leaving my seat after the performance when a “femme de chambre” handed me a note in which I found written in pencil the words:

“Mademoiselle Roxane is waiting for you in her coach at the theatre door.”

I could not believe the missive was intended for me; and I asked the abigail who had delivered it if she was not mistaken in the recipient.

“If I am mistaken,” she replied confidently, “then you cannot be Monsieur de Tournebroche, that is all.”

I ran to the coach which stood waiting in front of the House, and inside I recognized Mademoiselle B———, her head muffled in a black satin hood.

She beckoned to me to get in, and when I was seated beside her:

“Do you not,” she asked me, “recognize Sophie, whom you rescued from drowning on the banks of the Seine?”

“What! you! Sophie—Roxane—Mademoiselle B———, is it possible?—”

My confusion was extreme, but she appeared to view it without annoyance.

“I saw you,” she went on, “in one corner of the pit. I knew you instantly and played for you. Say, did I play well? I am so glad to see you again!—”

She asked me news of M. l’Abbé Coignard, and when I told her my good master had just perished miserably, she burst into tears.

She was good enough to inform me of the chief events of her life:

“My aunt,” she said, “used to mend her laces for Madame de Saint-Remi, who, as you must know, is an admirable actress. A short while after the night when you did me such yeoman service, I went to her house to take home some pieces of lace. The lady told me I had a face that interested her. She then asked me to read some verses, and concluded I was not without wits. She had me trained. I made my first appearance at the Comédie last year. I interpret passions I have felt myself, and the public credits me with some talent. M. le Duc de La ——— exhibits a very dear friendship for me, and I think he will never cause me pain and disappointment, because I have learnt to ask of men only what they can give. At this moment he is expecting me at supper. I must not break my word.”

But, reading my vexation in my eyes, she added:

“However, I have told my people to go the longest way round and to drive slowly.”

Notes

Erich Fried, ‘Es ist was es ist’ (1983).

Roxane in Jean-Baptiste Racine’s Bajazet: The character in Racine’s tragedy that Tournebroche discovers Sophie performing during the finale. Racine’s play of 1672 eerily echoes Coignard’s words about pride and conceit in love, and his reflection on the need to ‘love in humbleness of spirit’. It is based on a true story from the Turkish court of the time (or about thirty years earlier); a love triangle spawning a plot of power, conspiracy, deceit and murder, with the the sultana, Roxane, who is largely responsible for a chain of tragic events, ultimately committing suicide.

M. l’Abbé Coignard / Tournebroche: Central characters in Anatole France’s novel, At the Sign of the Reine Pédauque (La Rôtisserie de la reine Pédauque) (1892); and again as protagonist and narrator in The Opinions of Jerome Coignard (Les opinions de M. Jérôme Coignard Recueillies par Jacques Tournebroche) (1893).

The tower of the Chatelet: The Grand Chatelet, on the right bank of the Seine, contained the police HQ, courts and several prisons.

Les Halles: The Paris fresh food markets, demolished in 1971. They were the “stomach of Paris”, much loved, and written about by Emile Zola in his book of the same name.

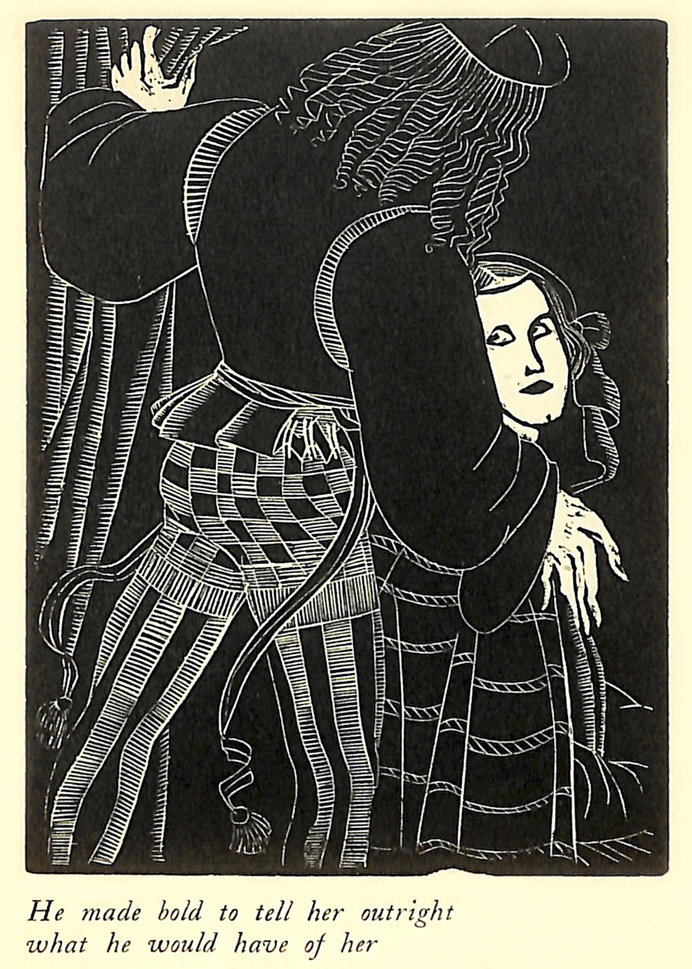

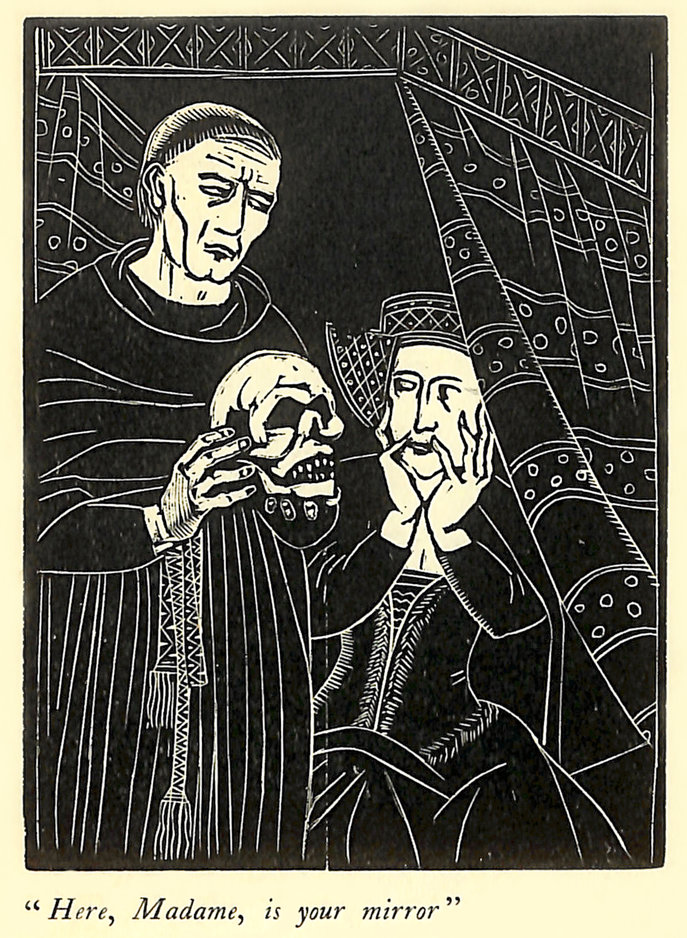

Note on France’s text and the illustrations: Translation of The Merrie Tales of Jacques Tournebroche is by Alfred Allinson (London: John Lane, Bodley Head, 1909). Woodcuts by British artist Marcia Lane Foster (1897–1983) have been confirmed as Public Domain Mark 1.0 (free of known restrictions under copyright law). Acknowledgement to David Widger for his digital edition.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

NIGHTSHIFT byTony Reck © 2025