Several of Smith’s writings for the London Journal, beginning in 1849, were illustrated by the artist Sir John Gilbert (1817–1897), knighted by Queen Victoria in 1872. These include his historical romance, Stanfield Hall; a domestic novel, Amy Lawrence, the Freemason’s Daughter; and Minnigrey, generally held to be his best work.

Frank Jay describes the ‘great draughtsman’s work’ as being ‘artistically conceived, vigorous in execution, and in treatment highly dramatic.’

An article entitled ‘Cheap Art’, in Macmillan’s Magazine (1859), refers to ‘the spirit and vigour of Mr Gilbert’s designs … [which are] an instance of the power of life-like art to attract an immense audience’. Along with J.F. Smith, he was perhaps an equal star of the London Journal.

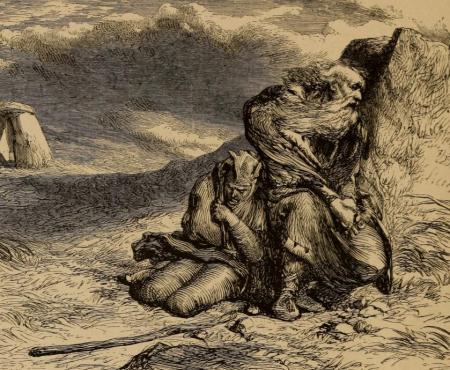

The following wood engraving is a great instance of the power of Gilbert’s work, in distilling in terms of visual feeling and motion the essence of Shakespeare’s lines:

Blow, blow, thou winter wind,

Thou art not so unkind

As man’s ingratitude;

Thy tooth is not so keen,

Because thou art not seen,

Although thy breath be rude.

The image featured in the present instalment, below, is not by Gilbert but the English painter George Elgar Hicks (1824–1914).

CHAPTER SEVEN

Close of the Examination — A False Friend Confounded — Our Hero and Lawyer Whiston Return to London

Richard Whiston was well-known in Essex, not only as a most respectable lawyer, but as agent for the estates of several of the largest land-owners in the county, Squire Tyrrel included in the number. He was a man of great tact, a little formal, perhaps, in his ideas, but of undoubted honesty. Under ordinary circumstances, his first act would have been to pay his respects to the wealthy magistrate; on the present occasion, however, he forbore to do so till he had shaken hands with his nephew and Goliah, who did not appear in the least surprised by the honour. Not so the Hursts, whose courage began to give way rapidly.

‘Ha, Whiston,’ said the squire, ‘glad to see you. What brings you from town? Place a chair,’ he added, to one of the servants.

The order was at once complied with, and a brief conversation, in a low tone of voice, ensued between the speaker and the lawyer.

‘Constables,’ said his worship, perceiving that the farmer and his wife were attempting to sneak quietly out of the court, ‘you will not suffer a single witness to quit the room without my permission. This affair has assumed a very different aspect. Send for Benoni Blackmore, the schoolmaster’s son. Stay,’ he added correcting himself. ‘My clerk will give you a summons. Meanwhile, we will hear the evidence of the prosecutor again.’

Peter Hurst, in a pitiable state of confusion, advanced towards the dais. Vainly he attempted to catch the eyes of Richard Whiston. They were turned persistently in another direction. A smile, or even a slight nod of recognition, would have been a consolation to him.

‘You accuse the prisoners of stealing a bay mare and covered market-waggon?’ said the magistrate.

‘Well, not exactly of stealing them,’ faltered the prosecutor. ‘They took them without leave.’

‘What! do you mean to go back on your sworn testimony?’ exclaimed the squire, indignanty. ‘There it is, in black and white, attested by your own signature. I fear I shall have to commit you for perjury.’

Drops of cold perspiration stood on the forehead of the farmer at hearing himself thus menaced. Most heartily did he wish that he had never learnt to write his name.

‘Perhaps you want your wife to prompt you?’ added the speaker, sarcastically. ‘Can’t be permitted. No tampering with justice in a court where I preside. Instead of standing there like a poor, hen-pecked idiot, wasting my time and the time of the court, answer my question instantly! Do you mean to go back on your sworn testimony?’

‘No, Squire, no,’ answered the old man, very meekly, ‘but somehow there has been a mistake. We only wanted to scare the lad, who has given himself a great many airs lately, and make him give up certain low companions whom we disapproved of. It was half in jest. Willie can come home, and be just as welcome as ever. That is all I have to say.’

‘Jest!’ repeated the magistrate, indignantly. ‘And do you mean to tell me that you have dared against the peace and dignity of our sovereign lord the king, the public safety, the respect due to this court and the laws of the realm — see the statutes in such cases provided — to take an oath in jest? You will find it a very dear one before I have done with you. Did any one incite — put you up to, or suggest this abominable conduct?’

‘His wife!’ shouted one or two voices at the lower end of the room — an interruption which was instantly repressed.

‘I have nothing more to say,’ faltered the farmer, loyally determined not to bring Peggy into the same predicament as himself.

‘Peter Hurst reflect!’

‘Nothing on that head,’ added the prosecutor, doggedly.

Benoni, accompanied by the officer who had been sent in search of him, now made his appearance in the court-room. Twice he attempted to meet the looks of the two friends, but his confidence failed him, and his eyes sank beneath their steadfast, honest gaze. William gave one sigh as his doubts were confirmed. The memory of his pretended friendship passed away, but the scar remained. Goliah did not indulge in a chuckle, nor even in a smile. He felt for his fellow prisoner’s disappointment.

On perceiving Lawyer Whiston seated by the side of the magistrate, the confusion of the hypocrite became pitiable. He wondered how he came there. There had not been time sufficient for intelligence of his nephew’s scrape to reach him by the ordinary post. He admitted that neither our hero nor Goliah knew anything respecting the boys, and that the former had commissioned him to explain the cause of his taking the mare and wagon.

‘Thee explained nothing of the kind!’ exclaimed Farmer Hurst. ‘All thee said wor that Willie and Goliah had gone off to London wi’ two gals.’

‘I was so confused,’ stammered Benoni.

William hastily wrote a few lines to Vickers, Chelmsford man of law.

‘With your worship’s permission, I wish to ask the witness a few questions.’

Strong in the presence of the great London practitioner, he had discarded much of his former cringing, servile tone.

The permission was granted.

‘Your name, I believe, is Blackmore?’

‘It is, sir.’

‘It will be difficult to wash such a blackmoor white.’ Here the little man looked round for applause, but receiving none, resumed the examination.

‘I presume, sir, you know the nature of an oath?’

‘I hope I do.’

‘Hope you do!’ repeated Vickers, delighted at finding someone he couId bully and the opportunity of airing his eloquence in presence of his London confrere.

‘Are you trifling with the honourable magistrate and the patience of the court? Are you not certain that you do?’

‘I am, sir.’

‘Quite certain?’

‘Quite certain,’ repeated Benoni.

‘Then, sir, on your oath, answer me. Were there not two prisoners, ruffians from the Bittern’s Marsh, who had attempted to rob, beat, or otherwise misuse the two boys in questions — that is, supposing they were boys — lying bound in the Red Barn?’

‘I believe so, sir.’

‘Now, who released them?’

The crowd in the justice-room stretched forth their heads, eager to catch the answer, which came hesitatingly and after a considerable pause.

‘I don’t know, sir.’

‘And that you swear to?’

‘Yes,’ said the witness, faintly.

‘Then you have sworn to a wicked lie!’ exclaimed a voice from the lower end of the room. ‘I saw you cut the cords that bound them, shake hands with them, and heard you bid them good-bye.’

‘Let that person come forward and give evidence,’ said Squire Tyrrel.

Blushing and trembling with indignation as well as modesty, Susan Hurst advanced to the dais. She swore that her curiosity being excited by the account she had heard, she crept down to the Red Barn, and peeping through the neatly closed doors, saw Benoni Blackmore, after a brief conversation with the two tramps, not only release them, but shake hands with them.

The witness looked around him; read scorn, loathing, and contempt on almost every face. With a cry of defiance, he sprang through one of the large windows of the justice-room, which had been opened to afford air, and fled with the fleetness of a deer across the park.

‘Let him go,’ said Squire Tyrrel. ‘The constables will know where to find him. As for the charge –‘

‘A word first,’ interposed Richard Whiston. ‘I cannot permit a doubt to remain as to the honesty of the prisoners’ intentions, or a suspicion to attach itself to the character of my nephew. The prosecutor has not yet proved that the mare and wagon are really his.’

Here Farmer Hurst felt himself strong.

‘That be a good un!’ he exclaimed. ‘There is not a man in Deerhurst but knows I bred Brown Bess myself.’

‘What was the name of her dam?’

‘Blackfoot. She wor born upon the farm.’

‘That is all I wish to elicit,’ said Lawyer Whiston, with a quiet smile. ‘And I move that William Whiston be honorably discharged. Half the farm is his; half the stock and agricultural implements. He could not rob himself.’

‘His friend, Goliah Gob,’ he added, ‘must be equally exonerated, as he acted under the authority of the part owner of the mare and wagon.’

Squire Tyrrel did not attempt to check the shouts which broke from the spectators at this positive, unanswerable proof of the prisoners’ innocence. When the noise had subsided he rose and said, with a certain amount of dignity:

‘William Whiston and Goliah Gob, you are both honorably discharged, and will leave the court-room without the slightest stain upon your characters. Whether you will bring an action against the prosecutor for false imprisonment and a still more serious charge, will, I presume, as you are still a minor, depend upon your legal guardian. It is no part of my duty,’ he added,’ to advise you on the subject.’

As the Hursts, humbled and disgraced in public opinion, were quitting the courtroom amid the jeers and hisses of the crowd, especially the female portion of it, William broke through them, and, taking Susan by the hand, kissed her most affectionately. All who witnessed the action appeared to understand the motive and a dead silence ensued. Even Peggy felt touched by it, and bitterly regretted her temper and headstrong folly.

‘The boy does love her after all,’ she thought,

A faint suspicion of the kind glanced across the mind of Goliah, but he instantly repelled it.

‘I beant agoin’ to doubt Willie,’ he muttered to himself.

The farmer, unable to endure the bitterness of his mortification, had no sooner passed through the lodge gates of Tyrrel Park than he darted down a by-lane, and never relaxed his speed till he reached his home, where he shut himself up in his own room, a prey to bitter reflection. As for Susan and her mother, he felt little or no uneasiness on their account. He knew that his nephew and Goliah would protect them. The lesson was a most severe one. Possibly he may profit by it. His wife, we fear, may have to learn a harder one yet.

When our hero repaired to the Tyrrel Arms, the only decent hotel in Deerhurst, he found Lawyer Whiston waiting for him rather impatiently. He thanked him most warmly for having so effectively cleared his character from suspicion.

‘Pooh!’ said the old bachelor. ‘I only did my duty.’

‘It was efficiently as well as shrewdly done, sir.’

‘Yes,’ observed his relative, complacently. ‘Poor Peter did not see the trap I laid for him. Where have you been?’

‘Seeing my aunt and cousin safely to the farm.’

The lawyer smiled.

‘Then you don’t feel very angry?’ he said.

‘I did at first; but that has passed away. You know how completely Uncle Hurst has been ruled by his wife. A great weakness, no doubt; but the habit of submission has become second nature to him — too late to change it.’

‘Then Susan will never rule you,’ observed his guardian.

William regarded him with surprise.

‘I saw the kiss you gave her,’ added the speaker.

‘That was gratitude, sir.’

‘Not love?’

‘Not in the sense you mean it,’ replied the youth with a smile. ‘Love, as the word is generally understood, has never troubled my imagination.’

Willie coloured slightly, doubtful, perhaps whether he were speaking quite disingenuously; but the suspicion passed away as an idle fancy.

‘I do love my cousin,’ he added, ‘for her truthfulness, her sense of right, her unwavering goodness to me — nothing more, I assure you.’

His hearer not only believed the assertion, but it appeared to afford him considerable satisfaction.

‘She is a noble-minded girl, and has acted well,’ he remarked. ‘Time enough to think of such folly ten years hence — that is, if ever you should think of it. She showed much presence of mind as well as courage in sending her letter to me by that ragged messenger. But probably you suggested it.’

‘I never heard of it till this morning in the justice-room, sir.’

‘All the more remarkable,’ observed Mr. Whiston. ‘The poor fellow appears to have received some sort of an education. Bad antecedents, I fear; great pity, for he rather interested me when he described the adventure in the Red Barn.’

‘Bunce?’ ejaculated William.

‘Yes, I think he told me that was his name.’

‘I trust, sir,’ said the nephew, earnestly, ‘that you did not dismiss him with a simple gratuity. You have no idea what a noble heart he has. Singly and at the risk of his life, he defended the two poor girls from their assailants. One of the ruffians was about to shoot him, when the young savage — you know who I mean,’ he added with a smile — ‘came to his assistance. I had nothing — positively nothing — to do with their deliverance. The merit is wholly theirs.’

‘At least I know where to find him again,’ answered the lawyer, somewhat evasively. ‘You must return to London with me.’

‘The very thing I wished, sir.’

‘To complete your education,’ added his relative gravely, ‘which I ought to have attended to more particularly than I have hitherto done. But boys grow so rapidly in these days that I sometimes ask myself if there are any left. I must be in London in the morning.’

‘That will give me time,’ replied our hero, ‘to say good-bye to the only friends in Deerhurst whom I shall regret, or who will regret me.’

‘Your cousin Susan?’ said the lawyer.

‘Yes sir.’

‘And Goliah Gob?’

‘The truest-hearted friend that ever man possessed.’

‘Ah!’ said Richard Whiston, musingly; ‘I begin to think so, too.’

We must pass over the adieux.

On the arrival of uncle and nephew in London they drove to the private residence of the former, a large, roomy house in Soho Square. It was handsomely, if not fashionably furnished. Our hero was conducted to a comfortable bedroom, directly facing the one occupied by his relative.

This is your home for the present,’ remarked the latter. ‘I have ordered dinner for you, although in all probability I shall not return in time to share it with you; but I will send you a friend.’

William regarded him inquiringly.

‘One whom I think you will be glad to meet. By the by, William, you would me oblige me greatly by promising me one thing.’

‘Anything,’ exclaimed the grateful youth.

‘Not to quit the house till I return. Most important case before the chancellor — scarcely in time — never kept his lordship waiting before.’

With a smile which expressed great kindness as well as satisfaction, the speaker took his leave to keep his appointment in the highest court of judicature in the kingdom, always excepting the house of peers.

After passing two or three hours in the library, William Whiston found that he could not fix his attention upon books. Not only did the last forty-eight hours appear like a dream to him — some moments he charged the girls he had rescued with ingratitude, the next he would have sworn they had excellent reasons for their conduct — sighed, wondered if he should ever see them again, then asked himself if he should wish to do so.

‘Doubtless they have forgotten me by this time, or are laughing at my credulity,’ he murmured. ‘No,’ he added, ‘there was a truthfulness in the voice and eyes of Kate — I scarcely noticed her companion — that assures me of her sincerity.’

It is an unmistakable sign of feelings stronger than curiosity when boys of sixteen indulge in such speculations. When the tones of a voice, heard but once, dwell upon the ear, making soft music — when weeping or laughing eyes haunt their sleep, we may be certain that the young, winged god is stealing an entrance to their hearts. Such, we fear, was the case with our hero. He was in love.

Girls, when they read this, will smile; papas and mammas look serious, as if they did not quite approve, till they regard each other in the face, when some recollection of their own youthful days will rest like a sunbeam on their countenances, and they will smile, too.

For our own part, we confess being an advocate of early love and early marriages, provided the object of our choice is a fitting one, and circumstances do not render them positively unwise. Like a mansion which at any moment may receive its tenant, the heart should be kept clean.

Day dreams sometimes make a more lasting impression than those which visit us in our sleep. William Whiston was still indulging in the former when his reveries were broken by the entrance of his uncle’s managing clerk, followed by a young man of about three or four and twenty, his countenance lit up by a bright, sunny smile, hope and excitement glowing in every feature.

‘I have brought the friend, sir, Mr Whiston promised to send to you,’ said a Mr. Prim; who, having delivered his message, instantly quitted the library.

His visitor advanced joyously towards our hero; but seeing that he was not recognised, said, sadly:

‘I perceive, sir, that you have forgotten me.’

The voice of the speaker dissipated the uncertainty of the dreamer; he recognised it instantly. Starting from his seat he cordially grasped his hand, and pronounced the name of Bunce.

‘This is indeed an unexpected pleasure,’ he exclaimed. ‘Pardon my seeming coldness; the metamorphosis is so great that I did not know you.’

‘It is so great,’ replied the poor tramp, ‘that I scarcely recognise myself. Suppose I shall in time, should the change last. For years I doubted the existence of such things as hearts; no such heresy now; owe it to your uncle. Gave him your cousin’s letter. What a man! What penetration! I could not even have lied to him — not that I felt the slightest inclination,’ he added, sadly, ‘although old habits are hard to overcome. I shall conquer them.’

‘You must forget the past,’ observed his hearer

‘It will never be forgotten,’ continued Bunce, ’till it is buried with me. With your cousin’s letter I gave him some papers and memoranda of my own which I had preserved since I was a child. The old woman who had charge of me told me they might one day be of service to me and advised me never to part with them. I never did so till I gave them to your uncle.’

‘Did he read them?’

‘Yes.’

‘And then?’

‘Placed them as carefully in his pocketbook as if they had been bank notes; after which he looked at me so earnestly that I, if I had told him a lie, felt certain he would have read it in my face.’

‘And the result?’

‘You may read it in my changed appearance,’ answered the tramp, spinning round gayly on one foot to display his new attire. ‘Boots that no longer leak; good warm clothes to keep out the cold winter; clean linen — ah I you don’t know what a luxury it is — hat, real beaver — no rabbit skin!’

‘Once more, my dear fellow,’ said William, ‘let me congratulate you. I spoke of your conduct to those poor girls to him before we quitted Deerhurst. He questioned me most minutely. His conduct to you has been better than I dared hope for. You have found a fulcrum at last.’

‘Ah, you recollect my using the word? I dare say you wondered how I came to know the meaning of it. As a boy I received some education. Would you like to hear my history?’

‘Yes, if you have no objections to the telling. The story must be interesting.’

‘It shall be the truth,’ observed the tramp, gravely. ‘This unexpected stroke of fortune may terminate as suddenly as it came. But I will not add to disappointment the reproach of having deceived you. Gratitude has placed a guard both on my imagination and my tongue.

‘Well, then,’ continued the speaker, after a pause, ‘my earliest recollections — perhaps I ought to say dreams — are of a house furnished far more sumptuously than this, and of a fair, delicate woman I believe to have been my mother. Yes,’ he added, musingly, ‘I feel certain she was my mother, for she loved me — and no one else ever did.’

‘Poor fellow!’ mentally ejaculated our hero.

‘An interval followed, of which I remember nothing certain. I think there was a funeral. I know that I was dressed in black. I know that for a long time I felt exceedingly unhappy, but, boy-like, gradually recovered both health and spirits. From that period my recollections are distinct, vivid as the forked lightning’s flash when it darts through a sombre cloud. I found myself in a sort of school kept by, I have no doubt, a very learned man; at least he was always reading.’

‘Did he ill-use you?’

‘No, not as the world would understand the question. But there was nothing genial in his disposition. He did his best to instruct us; there all thought and care appeared to end. I never recollect old Blackmore, as we used to call him, to procure us one pleasure or amusement.’

‘Whom did you say?’ demanded our hero, greatly surprised.

‘Old Blackmore.’

‘Was that his real name?’

‘I cannot tell,’ answered Bunce. ‘At least I never knew him by any other. He was a reserved and silent man. I question whether he really loved his own child, a boy about three years of age; at least he never caressed him.’

‘And his wife?’

‘Dead, I presume. An aged woman, who prepared our food, told me so. She had charge of everything — no very onerous task, seeing there were only four of us — in the old martello tower.’

‘I thought you told me that he kept a school,’ observed his hearer, fancying he had detected a discrepancy in the narrative.

‘I told you truly, but the rest of his pupils were day scholars — an unruly set, sons of smugglers, gypsies, tinkers, and ruffians inhabiting the Bittern’s Marsh. You cannot conceive a more savage, desolate place; tracts of land broken by swamps, with here and there open pools of water, no regular roads, mere bridle paths which could not be followed with out a guide, intersected by fallen trees, half-choked with rank grass which concealed many a dangerous pitfall.’

‘The Bittern’s Marsh!’ repeated William Whiston, as soon as he recovered from his surprise. ‘I thought you denied all knowledge of the place to the two ruffians you met in the barn.’

‘I told them that I was not a swamp-bird, and I told them truly. Not that I should have hesitated to have deceived them. My safety depended upon their not recognizing me. I knew them at the first glance, although twelve years at least had passed since we had met. The frankness of my confession, I see, has somewhat shaken your confidence in me,’ added the speaker, sadly. ‘I cannot help it. You did not expect a life like mine to be a tale of pleasure.’

‘Heed not my interruption,’ said our hero. ‘Pray proceed.’

This edition © 2019 Furin Chime, Michael Guest

Notes and Reading

On Gilbert, for instance, see Frank Jay, Peeps into the Past (1919). His wood engraving is on page 14 of Shakspere’s Songs and Sonnets, Illustrated by John Gilbert (1870 — 77?). A facsimile is available to read online at HathiTrust Mobile Digital Library.

Interesting book by George Elgar Hicks, A Guide to Figure Drawing (1853) is available to read online in facsimile at Google Books.

‘”Nothing on that head,” said the prosecutor’: ‘on that head’, meaning ‘on that topic/issue/point’ or ‘under that heading’, is an expression that used to be common but has fallen into disuse. I was slightly thrown here until I recalled that Mr. Hurst is referred to as ‘the prosecutor’, since it is he mounting the case against William and Goliah.

‘blackmoor’: An archaic, offensive term for a person of colour. Benoni Blackmore is Caucasian, his family probably hailing from Blackmore, in Essex, but the pun is intended as a moral barb. Note that Smith uses the word in a satirical gesture aimed against the idiocy of the character who mouths it.