In my translator’s preface to Saneatsu Mushanokoji’s The Innocent (Omedetaki Hito of 1911), I noted a curious feature of the novella: Mushanokoji seems to anticipate aspects of very modern writers such as Samuel Beckett and Italo Calvino in particular. Mushanokoji’sThe Innocent intriguingly prefigures elements of Beckett’s minimalism and Calvino’s conceptual play, bridging literary traditions in a way that feels startlingly modern to contemporary readers.

The preeminent scholar of Japanese modernism Donald Keene (1922 – 2019) may overlook Mushanokoji’s continuing and extensive potential, I feel, when he excludes him from relevance beyond his own milieu. Moreover, Keene was so imposing a figure, I suggest, that his oversight impeded translation of the work, although it is given frequent reference in critical discussions of Japanese modernism.

Keene writes that Mushanokoji is

more likely to be remembered for his humanitarian ideals and his writings on art than for his works of fiction. His popularity has lingered on, but his works seem to belong to another age.

Dawn to the West: Japanese literature of the Modern Era (New York : Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1984 [p. 457])

But I detect a disarming self-parodic strain in Mushanokoji’s novella, which has an effect of undermining (to a calculated extent) the absolute self-centeredness of the anti-hero “Jibun” (= “myself”) of the seminal I-novel. This obsession of Jibun’s is the very mechanism by which the narrative is enabled to spiral inward into the self, at the same time reducing his beloved Tsuru to a phantasm. It strains credibility that Jibun never once speaks with Tsuru, while remaining rational and empathetic in other respects. The inwardly moving spiral traced by the story is equally an effect of form and structure, such as we see where Jibun continues exploring the inner self in “addenda” to the main narrative, where Calvino-esque pieces are to be found, alongside little “Beckettian” dramas. Keene’s naturalistic reading overlooks the novella’s deliberate self-parody and its experimental form.

At any rate, serving as a conduit, so to speak, for the apparent prescience of this, Mushanokoji’s first published work, is the impact that the Belgian playwright and Nobel Prize in Literature laureate Maurice Maeterlinck was having upon Mushanokoji at the time he was writing The Innocent. This sense of spiraling inwardness and abstraction links Mushanokoji directly to Maeterlinck, whose aesthetics of individualism and metaphysical exploration were pivotal during the novella’s composition. One tends to skim over the significant single reference to Maeterinck in Chapter 4:

I have not seen her for almost a year. I have never spoken to her. Nonetheless, I believe that during the past three to four years, our hearts have not been strangers. It is a selfish belief, but I have held such thoughts for some years now, ever since I began seriously reading Maeterlinck.

The Innocent, Mushanokoji, translated by Michael Guest, (Sydney: Furin Chime, 2024) p. 37

Mushanokoji hitherto adopted Leo Tolstoy as his literary idol, but by the time he wrote The Innocent, had “graduated” from the Russian naturalist to the Belgian symbolist; reading Tolstoy, Mushanokoji wrote, now “gave [him] headaches” because of his prudery (Keene 451). Instead, he leaned towards Maeterlinck’s aesthetics of individualism.

It is Beckett’s appropriation of the Belgian mystic that provides us with a direct connection toThe Innocent. By the time of Godot and Endgame, the symbolist theatre of Maeterlinck with its lack of plot and love of silence, had lost some currency: an American college student is memorialized as responding, when asked who Maurice Maeterlinck was, that he was the “king of Abyssinia” (William Lyon Phelps, “An Estimate of Maeterlinck,” North American Review 213.782 [Jan., 1921]). Beckett gives these theatrical aesthetics a new breath of life, while revivifying their metaphysical themes.

Peter Szondi identifies Maeterlinck’s profound perception — a defining realization that recurs throughout Beckett’s oeuvre:

In Maeterlinck’s work only a single moment is dealt with, the moment when a helpless human being is overtaken by fate (32).

Theory of the Modern Drama, trans. M. Hayes (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1987)

It is so Beckettian, and essentially the same metaphysical thematic is at the bottom of two dramaticules in “addenda” to Mushanokoji’s The Innocent.

Over my next couple posts, I will present an edition of Maeterlinck’s play, The Blind (Les Aveugles 1890) which strikingly demonstrates its significance for Beckett’s writing. Stark simplicity and themes of existential waiting resonate deeply with Beckett’s most iconic plays.

Ashley Taggart writes of the “thematic debt owed by Beckett to Maeterlinck” identifiable in this work.

Set in an indeterminate time, the situation depicted has a characteristic simplicity: six blind men and six blind women have been led out from their “asylum” for the day by an old priest. At a clearing in the forest, they stop, and, unknown to the others, the priest dies in their midst. Meanwhile, the blind await his return (from what they think is an excursion in search of bread and water) with mounting anxiety. That’s it. They sit around and wait, a la Godot, but in this case for the priest, whose lifeless body is slumped against a tree in between the men and the women. You could say it’s a one-act play minus the act.

Maeterlinck and Beckett: Paying Lip-Service to Silence (Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd’hui, Vol. 22, Samuel Beckett: Debts and Legacies [2010]}

It is impossible to overlook the tonal and thematic features, broad and detailed, present in Maeterlink’s play, that Beckett lavishes in Waiting for Godot (1948/54) and Endgame (1957). Beckett’s deep engagement with Maeterlinck demonstrates the enduring relevance of these themes, which also reverberate in the background of Mushanokoji’s The Innocent.

The Blind

To Charles Van Lerberghe

An ancient Norland forest, with an eternal look, under a sky of deep stars. In the centre, and in the deep of the night, a very old priest is sitting, wrapped in a great black cloak. The chest and the head, gently upturned and deathly motionless, rest against the trunk of a giant hollow oak. The face is fearsome pale and of an immovable waxen lividness, in which the purple lips fall slightly apart. The dumb, fixed eyes no longer look out from the visible side of Eternity and seem to bleed with immemorial sorrows and with tears. The hair, of a solemn whiteness, falls in stringy locks, stiff and few, over a face more illuminated and more weary than all that surrounds it in the watchful stillness of that melancholy wood. The hands, pitifully thin, are clasped rigidly over the thighs.

On the right, six old men, all blind, are sitting on stones, stumps and dead leaves.

On the left, separated from them by an uprooted tree and fragments of rock, six women, also blind, are sitting opposite the old men. Three among them pray and mourn without ceasing, in a muffled voice. Another is old in the extreme. The fifth, in an attitude of mute insanity, holds on her knees a little sleeping child. The sixth is strangely young, and her whole body is [*62] drenched with her beautiful hair. They, as well as the old men, are all clad in the same ample and sombre garments. Most of them are waiting, with their elbows on their knees and their faces in their hands; and all seem to have lost the habit of ineffectual gesture and no longer turn their heads at the stifled and uneasy noises of the Island. Tall funereal trees, — yews, weeping willows, cypresses, — cover them with their faithful shadows. A cluster of long, sickly asphodels is in bloom, not far from the priest, in the night. It is unusually oppressive, despite the moonlight that here and there struggles to pierce for an instant the glooms of the foliage.

FIRST BLIND MAN (who was born blind): He hasn’t come back yet?

SECOND BLIND MAN (who also was born blind): You have awakened me.

FIRST BLIND MAN: I was sleeping too.

THIRD BLIND MAN (also born blind): I was sleeping, too.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

He hasn’t come yet?

SECOND BLIND MAN.

I hear nothing coming. [*63]

THIRD BLIND MAN.

It is time to go back to the Asylum.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

We ought to find out where we are.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

It has grown cold since he left.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

We ought to find out where we are!

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN,

Does anyone know where we are?

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

We were walking a very long while; we must be a long way from the Asylum.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

Oh! the women are opposite us?

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

We are sitting opposite you.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

Wait, I am coming over where you are. [He rises and gropes in the dark.] — Where are you? — Speak! let me hear where you are! [*64]

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

Here; we are sitting on stones.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

[Advances and stumbles against the fallen tree and the rocks.] There is something between us.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

We had better keep our places.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

Where are you sitting? — Will you come over by us?

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

We dare not rise!

THIRD BLIND MAN.

Why did he separate us?

FIRST BLIND MAN.

I hear praying on the women’s side.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

Yes; the three old women are praying.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

This is no time for prayer! [*65]

SECOND BLIND MAN.

You will pray soon enough, in the dormitory! [The three old women continue their prayers.]

THIRD BLIND MAN.

I should like to know who it is I am sitting by.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

I think I am next to you. [They feel about them.]

THIRD BLIND MAN.

We can’t reach each other.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

Nevertheless, we are not far apart. [He feels about him and strikes with his staff the fifth blind man, who utters a muffled groan.] The one who cannot hear is beside us.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

I don’t hear everybody; we were six just now.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

I am going to count. Let us question the women, too; we must know what to depend upon. I hear the three old women praying all the time; are they together?

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

They are sitting beside me, on a rock. [*66]

FIRST BLIND MAN.

I am sitting on dead leaves.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

And the beautiful blind girl, where is she?

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

She is near them that pray.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

Where is the mad woman, and her child?

THE YOUNG BLIND GIRL.

He sleeps; do not awaken him!

FIRST BLIND MAN.

Oh! how far away you are from us! I thought you were opposite me!

THIRD BLIND MAN.

We know – nearly – all we need to know. Let us chat a little, while we wait for the priest to come back.

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

He told us to wait for him in silence.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

We are not in a church.

THF VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

You do not know where we are.

[*67]

THIRD BLIND MAN.

I am afraid when I am not speaking,

SECOND BLIND MAN.

Do you know where the priest went?

THIRD BLIND MAN.

I think he leaves us for too long a time.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

He is getting too old. It looks as though he himself has no longer seen for some time. He will not admit it, for fear another should come to take his place among us; but I suspect he hardly sees at all anymore. We must have another guide; he no longer listens to us, and we are getting too numerous. He and the three nuns are the only people in the house who can see; and they are all older than we are! — I am sure he has misled us and that he is looking for the road. Where has he gone? — He has no right to leave us here. . . .

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

He has gone a long way: I think he said so to the women.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

He no longer speaks except to the women?

— Do we no longer exist? — We shall have to complain of him in the end. [*68]

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

To whom will you complain?

FIRST BLIND MAN.

I don’t know yet; we shall see, we shall see. — But where has he gone, I say? — I am asking the women.

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

He was weary with walking such a long time. I think he sat down a moment among us. He has been very sad and very feeble for several days. He is afraid since the physician died. He is alone. He hardly speaks anymore. I don’t know what has happened. He insisted on going out today. He said he wished to see the Island, a last time, in the sunshine, before winter came. The winter will be very long and cold, it seems, and the ice comes already from the North. He was very uneasy, too: they say the storms of the last few days have swollen the river and all the dikes are shaken. He said also that the sea frightened him; it is troubled without cause, it seems, and the coast of the Island is no longer high enough. He wished to see; but he did not tell us what he saw. — At present, I think he has gone to get some bread and water for the mad woman. He said he would have to go, a long way, perhaps. We must wait.

[*69]

THE YOUNG BLIND GIRL.

He took my hands when he left; and his hands shook as if he were afraid. Then he kissed me.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

Oh! oh!

THE YOUNG BLIND GIRL.

I asked him what had happened. He told me he did not know what was going to happen. He told me the reign of old men was going to end, perhaps.…

FIRST BLIND MAN.

What did he mean by saying that?

THE YOUNG BLIND GIRL.

I did not understand him. He told me he was going over by the great lighthouse.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

Is there a lighthouse here?

THE YOUNG BLIND GIRL.

Yes, at the north of the Island. I believe we are not far from it. He said he saw the light of the beacon even here, through the leaves. He has never seemed more sorrowful than today, and I believe he has been weeping for several days. I do not know why, but I wept also without seeing him. I did not hear [*70] him go away. I did not question him any further. I was aware that he smiled very gravely; I was aware that he closed his eyes and wished to be silent.…

FIRST BLIND MAN.

He said nothing to us of all that!

THE YOUNG BLIND GIRL.

You do not listen when he speaks!

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

You all murmur when he speaks!

SECOND BLIND MAN.

He merely said “Good-night” to us when he went away.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

It must be very late.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

He said “Good-night” two or three times when he went away, as if he were going to sleep. I was aware that he was looking at me when he said “Good-night; good-night.” — The voice has a different sound when you look at anyone fixedly.

FIFTH BLIND MAN.

Pity the blind!

[*71]

FIRST BLIND MAN.

Who is that, talking nonsense?

SECOND BLIND MAN.

I think it is he who is deaf.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

Be quiet! — This is no time for begging!

THIRD BLIND MAN.

Where did he go to get his bread and water?

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

He went toward the sea.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

Nobody goes toward the sea like that at his age!

SECOND BLIND MAN.

Are we near the sea?

THE OLD BLIND WOMAN.

Yes; keep still a moment; you will hear it.

[Murmur of a sea, nearby and very calm, against the cliffs.]

SECOND BLIND MAN.

I hear only the three old women praying.

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

Listen well; you will hear it across their prayers.

[*72 ]

SECOND BLIND MAN

Yes; I hear something not far from us.

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

It was asleep; one would say that it awaked.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

He was wrong to bring us here; I do not like to hear that noise.

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

You know quite well the Island is not large. It can be heard whenever one goes outside the Asylum close.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

I never listened to it.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

It seems close beside us today; I do not like to hear it so near.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

No more do I; besides, we didn’t ask to go out from the Asylum.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

We have never come so far as this; it was needless to bring us so far.

[*73]

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

The weather was very fine this morning; he wanted to have us enjoy the last sunny days, before shutting us up all winter in the Asylum.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

But I prefer to stay in the Asylum.

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

He said also that we ought to know something of the little Island we live on. He himself had never been all over it; there is a mountain that no one has climbed, valleys one fears to go down into, and caves into which no one has ever yet penetrated. Finally he said we must not always wait for the sun under the vaulted roof of the dormitory; he wished to lead us as far as the seashore. He has gone there alone.

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

He is right. We must think of living.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

But there is nothing to see outside!

SECOND BLIND MAN.

Are we in the sun, now?

THIRD BLIND MAN.

Is the sun still shining?

[*74]

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

I think not: it seems very late.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

What time is it?

THE OTHERS.

I do not know. — Nobody knows.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

Is it light still? [To the sixth blind man.] — Where are you? — How is it, you who can see a little, how is it?

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

I think it is very dark; when there is sunlight, I see a blue line under my eyelids. I did see one, a long while ago; but now, I no longer perceive anything.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

For my part, I know it is late when I am hungry: and I am hungry.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

Look up at the sky; perhaps you will see something there!

[All lift their heads skyward, with the exception of the three who were born blind, who continue to look upon the ground.]

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

I do not know whether we are under the sky.

[*75]

FIRST BLIND MAN.

The voice echoes as if we were in a cavern.

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

I think, rather, that it echoes so because it is evening.

THE YOUNG BLIND GIRL.

It seems to me that I feel the moonlight on my hands.

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

I believe there are stars: I hear them.

THE YOUNG BLIND GIRL.

So do I.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

I hear no noise.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

I hear only the noise of our breathing.

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

I believe the women are right.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

I never heard the stars.

THE TWO OTHERS WHO WERE BORN BLIND.

Nor we, either.

[A flight of night birds alights suddenly in the foliage]

[*76]

SECOND BLIND MAN.

Listen! Listen! — what is up there above us? — Do you hear?

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

Something has passed between us and the sky!

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

There is something stirring over our heads; but we cannot reach there!

FIRST BLIND MAN.

I do not recognize that noise. — I should like to go back to the Asylum.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

We ought to know where we are!

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

I have tried to get up; there is nothing but thorns about me; I dare not stretch out my hands.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

We ought to know where we are!

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

We cannot know!

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

We must be very far from the house. I no longer understand any of the noises.

[*77]

THIRD BLIND MAN.

For a long time I have smelled the odor of dead leaves —

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

Is there any of us who has seen the Island in the past, and can tell us where we are?

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

We were all blind when we came here.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

We have never seen.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

Let us not alarm ourselves needlessly. He will come back soon; let us wait a little longer. But in the future, we will not go out any more with him.

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

We cannot go out alone.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

We will not go out at all. I had rather not go out.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

We had no desire to go out. Nobody asked him to.

[*78]

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

It was a feast-day in the Island; we always go out on the great holidays.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

He tapped me on the shoulder while I was still asleep, saying: “Rise, rise; it is time, the sun is shining!” — Is it? I had not perceived it. I never saw the sun.

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

I have seen the sun, when I was very young.

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

So have I; a very long time ago; when I was a child; but I hardly remember it any longer.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

Why does he want us to go out every time the sun shines? Who can tell the difference? I never know whether I take a walk at noon or at midnight.

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

I had rather go out at noon; I guess vaguely then at a great white light, and my eyes make great efforts to open.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

I prefer to stay in the refectory, near the seacoal fire; there was a big fire this morning….

[*79]

SECOND BLIND MAN.

He could take us into the sun in the courtyard. There the walls are a shelter; you cannot go out when the gate is shut, — I always shut it. — Why are you touching my left elbow?

FIRST BLIND MAN.

I have not touched you. I can’t reach you.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

I tell you somebody touched my elbow!

FIRST BLIND MAN.

It was not any of us.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

I should like to go away.

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

My God! My God! Tell us where we are!

FIRST BLIND MAN.

We cannot wait for eternity.

[A clock, very far away, strikes twelve slowly.]

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

Oh, how far we are from the asylum!

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

It is midnight.

[*80]

SECOND BLIND MAN.

It is noon. — Does anyone know? — Speak!

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

I do not know, but I think we are in the dark.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

I don’t know any longer where I am; we slept too long —

SECOND BLIND MAN.

I am hungry.

THE OTHERS.

We are hungry and thirsty.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

Have we been here long?

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

It seems as if I had been here centuries!

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

I begin to understand where we are …

THIRD BLIND MAN.

We ought to go toward the side where it struck midnight…

[All at once the night birds scream exultingly in the darkness.]

[*81]

FIRST BLIND MAN.

Do you hear? — Do you hear?

SECOND BLIND MAN.

We are not alone here!

THIRD BLIND MAN.

I suspected something a long while ago: we are overheard. — Has he come back?

FIRST BLIND MAN.

I don’t know what it is: it is above us.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

Did the others hear nothing? — You are always silent!

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

We are listening still.

THE YOUNG BLIND GIRL.

I hear wings about me!

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

My God! my God I Tell us where we are!

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

I begin to understand where we are.… The Asylum is on the other side of the great river; we crossed the old bridge. He led us to the north of the Island. We are not far from the [*82] river, and perhaps we shall hear it if we listen a moment.… We must go as far as the water’s edge, if he does not come back. . . . There, night and day, great ships pass, and the sailors will perceive us on the banks. It is possible that we are in the wood that surrounds the lighthouse; but I do not know the way out.… Will anyone follow me?

FIRST BLIND MAN.

Let us remain seated! — Let us wait, let us wait. We do not know in what direction the great river is, and there are marshes all about the Asylum. Let us wait, let us wait.… He will return…. he must return!

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

Does anyone know by what route we came here? He explained it to us as he walked.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

I paid no attention to him.

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

Did anyone listen to him?

THIRD BLIND MAN.

We must listen to him in the future.

SIXTH BLIND MAN.

Were any of us born on the Island?

[*83]

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

You know very well we came from elsewhere.

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

We came from the other side of the sea.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

I thought I should die on the voyage.

SECOND BLIND MAN.

So did I; we came together.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

We are all three from the same parish.

FIRST BLIND MAN.

They say you can see it from here, on a clear day, — toward the north. It has no steeple.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

We came by accident.

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

I come from another direction.…

SECOND BLIND MAN.

From where?

THE VERY OLD BLIND WOMAN.

I dare no longer dream of it…. I hardly remember any longer when I speak of it.… It was too long ago…. It was colder there than here.…

[*84]

THE YOUNG BLIND GIRL.

I come from very far.…

FIRST BLIND MAN.

Well, from where?

THE YOUNG BLIND GIRL.

I could not tell you. How would you have me explain! — It is too far from here; it is beyond the sea. I come from a great country.… I could only make you understand by signs: and we no longer see. I have wandered too long.… But I have seen the sunlight and the water and the fire, mountains, faces, and strange flowers.… There are none such on this Island; it is too gloomy and too cold…. I have never recognized their perfume since I saw them last.… And I have seen my parents and my sisters…. I was too young then to know where I was.… I still played by the seashore.… But oh, how I remember having seen!… One day I saw the snow on a mountain-top… I began to distinguish the unhappy…

FIRST BLIND MAN.

What do you mean?

THE YOUNG BLIND GIRL.

I distinguish them yet at times by their voices…. I have memories which are clearer when I do not think upon them….

[* 85]

FIRST BLIND MAN.

I have no memories.

[A flight of large migratory birds pass clamorously, above the trees.]

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

Something is passing again across the sky!

SECOND BLIND MAN.

Why did you come here?

THE VERY OLD BLIND MAN.

Of whom do you ask that?

SECOND BLIND MAN.

Of our young sister.

THE YOUNG BLIND GIRL.

I was told he could cure me. He told me I would see some day; then I could leave the Island.…

FIRST BLIND MAN.

We all want to leave the Island!

SECOND BLIND MAN.

We shall stay here always.

THIRD BLIND MAN.

He is too old; he will not have time to cure us.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

- In Maurice Maeterlinck, The Intruder: The Blind; The Seven Princesses; The Death of Tintagiles, translated by Richard Hovey, NY: Dodd, Mead, and Company, 1911. Page numbers in the text (*) are from this edition.

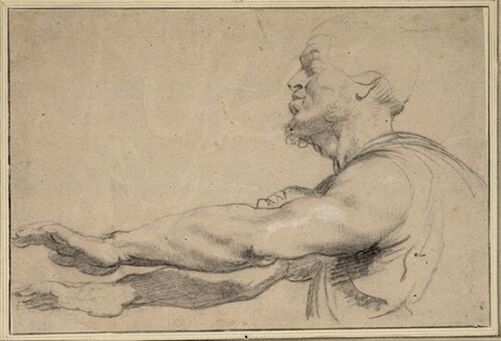

- Featured image is The Blind Leading the Blind by Pieter Breughel the Elder, 1568