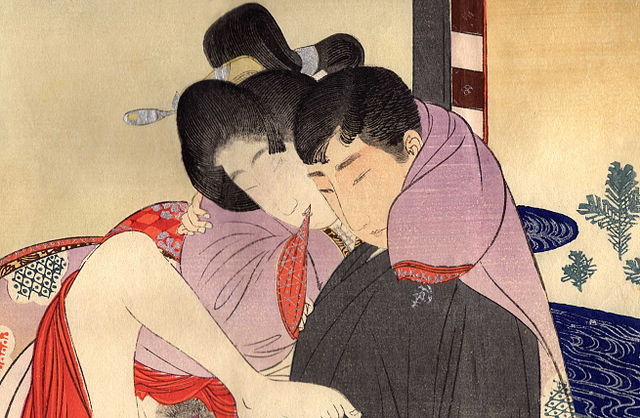

In Chapter Three, Jibun attends an alumni reunion, where he is offended by some of the mildly off-colour gossip shared by his former classmates. His beloved Tsuru is not far from his thoughts at any time, an object of absolute purity. I have borrowed an anonymous erotic artwork from late in the Meiji era (1868-1912), in emphasizing the perceived contrast with his more lewd acquaintances, though despite Jibun’s disgust, they actually seem quite tame. It is interesting to note the short haircut of the man, which marks the image clearly as Meiji, a period when Japan was rapidly absorbing Western influences, fashions, and technologies.

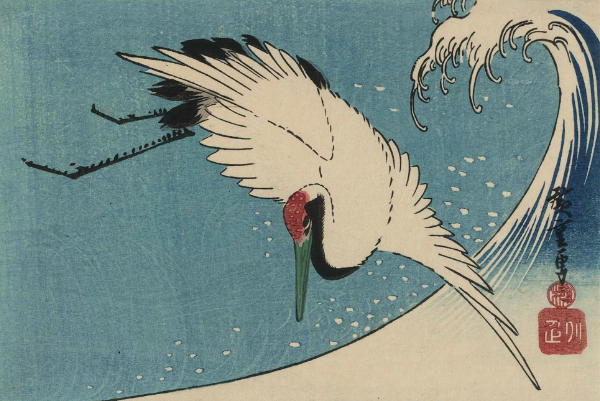

This particular genre of art is called shunga, and dates from the fourteenth century. Shunga means ‘spring picture’ — ‘spring’ being a euphemism for ‘sex’. The brilliant artist Hokusai was famous for his shunga prints, as well as for his ukiyoe (‘pictures of the floating world’).

In this chapter of the Exploratory Companion, let’s begin to consider a little of Jibun’s and Mushanokoji’s philosophy. As well, I’d like to look at the introduction and evolution of transport technology in Japan, and in particular Tokyo. What a superb system it has become. We can still see the Meiji slogan in action: “Japanese spirit, Western techology”!

Jibun as a ‘moral philosopher’

The term dogakusha, which Jibun uses to describe his “occupation” as a “moral scholar,” literally translates as “scholar of the way” — the (Chinese) way of the Tao, as in Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching (“the way of integrity”). Strictly speaking, it means “Taoist scholar,” which is inapt here. By late Meiji, the term could refer to a Confucian philosopher or simply a moralist. It also took on a mocking connotation, describing an eccentric scholar so preoccupied with morality and reason as to be oblivious to worldly affairs. To some extent, Mushanokoji seems to be poking fun at himself in adopting this role (See my note to Translator’s Preface, The Innocent). His philosophy is a free-sprited amalgam of ideas from East and West.

Here one may find the spirit of masculine fortitude comparable to Nietzsche’s amor fati [Lat. ‘Love of one’s fate’] but Saneatsu’s affirmative attitude has more affinity to the meditative state of mind, typical of the Zen sect, attained by the Oriental sages.

Okazaki (Toyo Bunko) 312

Musha-ism: Happiness Through Self-Transcendence

The alumni meeting scene explicitly raises Jibun’s philosophical aspirations. Yoshihiro Mochizuki’s MA thesis on Musha-ism — Mushanokoji’s theory of happiness — proves a useful reference, in its framing of happiness as a function of self-transcendence: transcendence effected via the self.

Our marriage would make a good topic for gossip, and those fools [the alumni] might still try ridiculing me.

The Innocent, Ch. 3: 33

If they did, I would answer them like this:

“Yes, it was love at first sight and we married. I am sorry to say that I cannot be interested in as many women as you are because I know something of true love. I cannot do everything.”

While I spoke, I would make an expression as though I were biting through a bitter-tasting bug. It would be most awkward. Yet I am unable to rise above reacting like this.

If I am able to transcend that, I am already no longer a moral scholar. No longer an educator.

Mochizuki examines Musha-ism as a philosophy of happiness, defined as self-cultivation and self-transcendence. He identifies two levels in The Innocent: a deeper philosophical aspect and a more superficial narrative of Jibun’s pursuit of Tsuru, in which he relegates her to a purely subjective sphere.

Whenever I see a female student of her age, or a woman coming from a distance, or a woman from behind, whatever the time or place, I wonder whether it might be Tsuru. I can notice this tendency increasing, little by little. Ten times out of ten it would not be her.

Ch. 3: 30

And yet still I wonder.

Rather than attempt to prescribe any specific (and inevitably somewhat arbitrary) reading, it may be more productive in general to consider how a reader is free to receive elements from these levels, assembling one’s own interpretation. Such an approach would well align with Mushanokoji’s own progressive aims. His author’s dedication for The Innocent, for instance, privileges the reader’s free response:

I believe in a selfish kind of literature, a literature for its own sake. It is only in accord with this idea that I desire to be an author. The value of my writing is determined by the degree to which it can harmonize with the reader’s own individuality. I am not entitled to demand that people unable to empathize with me should buy or read what I write.

Glancing at a few elements of Musha-ism in The Innocent will suffice to give us a notion of the author’s intentions. For a comprehensive view, we can turn to Mochizuki’s thesis.

The Shirakaba Group and the Cultivation of the Self

Mushanokoji was a founder and leading figure of the Shirakaba-ha (White Birch Society), a literary coterie at the Gakushuin (Peers’ School) in Tokyo, whose members included several prominent writers. Under his leadership, the Shirakaba group “led the humanitarian movement of the Taisho era” (Toyo Bunko, Okazaki comp., Japanese Literature in the Meiji Era, 1955). As an elite group of aristocratic youths in their early twenties, they faced minimal restrictions on their artistic ambitions. Their philosophy centered on art for art’s sake and self-cultivation — transcendence through the self — with a pronounced avant-garde inclination.

What is of utmost importance is my Self, the development of my Self, the growth of my Self, the fulfillment of my self in the true sense of the word… I love Power, I love Life, I love Thought. But that is all because I love my Self, because I want to develop my Self, and want to give life to my Self…. I will not sacrifice myself for anything. (52-3)

Qtd. in Tomo Suzuki, Narrating the Self: Fictions of Japanese Modernity (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford UP, 1951)

Subtle avant-garde elements of The Innocent have tended to marginalize it, accounting for a lack of interest from potential translators. Missing the point, certain types of reader have dismissed the novella as confused and immature, misconstruing its disarming self-parody. Fortunately, at the same time, these progressive characteristics appeal to a late modern, who has become historically conditioned to them. To such a reader, the novella offers a vital doorway into a dynamic experience of the Meiji imagination.

Besides mere primitive simplicity, [The Innocent] displays also a considerable degree of self-consciousness, self-analysis, and self satirizing. In a sense, Saneatsu seems to have been presenting such a pointless sort of comedy knowingly. He seems also to have resigned himself to the destiny of human beings who are impressed with their own goodness while satirizing themselves, and obliged to live after all by approving of their behavior just as it is, even though they sometimes try to deny themselves.

Okazaki, Toyo Bunko 312

Such a total immersion in the Self is evident in the way Jibun’s love for Tsuru is circumscribed in his own subjectivity. He places her on a pedestal of the ideal, while remaining anonymous and never even speaking to her.

Unfortunately, I crave a beautiful young woman. I have not even spoken to one since Tsukiko, my crush when I was nineteen, returned to her hometown seven years ago, and now I hunger for a woman.

Ch. 1: 17

It is an almost absurdist feature of the story, this apparent descent into solipsism — being completely bound up in the self. Moreover, as we will see, the untenable existential situation will inevitably place Jibun into conflict with his idealistic love for Tsuru: just what sacrifices would he be prepared to make for her, if any? He is caught in something of a vicious cycle or reductio ad absurdum, without realizing it.

How terrible it would be for her to come to me feeling she would be happier somewhere else!

Ch. 4: 37

If she were to accept my proposal joylessly, then I would have to withdraw it. By nature, I am a moralist.

And as such, an extreme individualist.

I am against sacrificing myself in the slightest for the sake of another person and would be ashamed to sacrifice another in my own interest.

Jibun cannot help become an object of self-parody. This flows from his continual self-questioning and moralising, as much as from his obsessiveness about his beloved Tsuru, with whom he has never even spoken.

Yet Jibun remains a close proxy for the author, the utopian philosopher Mushanokoji himself. Towards the end of the chapter, in Jibun’s thoughts, I believe, can be observed a subtle ambivalence that lies at the heart of a serious aspiration to self-transcendence.

Musha-ism tends to produce an anti-naturalistic, what might be called “decadent” stylistic turn, particularly an opposition to a mechanistic idea of nature then holding sway (Okazaki, Toyo Bunko, 312). During his Tolstoyan phase, Mushanokoji had sought like his then luminary to “love his neighbor as himself”; his adoption of Maeterlinck’s ideas saw a shift in this attitude. Mushanokoji’s transition from following a Tolstoyan mode of humanism to Maurice Maeterlinck’s (see earlier Furin Chime posts on Maeterlinck) further involves a turn from self-denial and asceticism, to the affirmation of pleasure.

You are told you should love your neighbour as yourself; but if you love yourself meanly, childishy, timidly, even so shall you love your neigbour. Learn therefore to love yourself with a love that is wise and healthy, that is large and complete.

Maeterlinck, qtd. in Mochizuki, 46

As I argued in my posts on Maeterlinck, the various anti-naturalistic, humanistic, absurdist, and metaphysical thematics of The Innocent serve to make it quite accessible and sympatico with a modern reader, more than the theory of Musha-ism per se. Rather, it is thanks to Maeterlinck’s influence on Samuel Beckett and Beckett’s appropriation of Maeterlinck; and to the profound influence Beckett has had upon the human imagination since the 50s and 60s.

Locating The Innocent in time and space: Meiji-Taisho Tokyo rail

I should say a few words regarding a technical detail of translation.

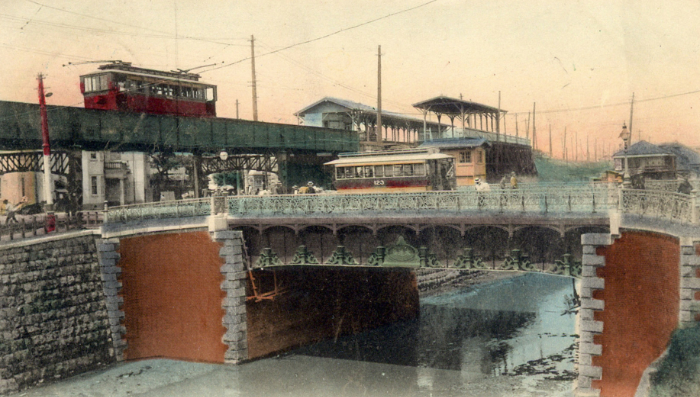

Tokyo’s transportation landscape underwent a significant transformation during the Meiji and Taisho eras. It began in 1871 with the introduction of horse-drawn carriages, initially a luxury for the elite. Public horse-drawn carriages soon followed, providing transport within Tokyo and to surrounding areas. By 1882, horse-drawn trams, running on rails, gained popularity, but sanitation issues prompted a shift towards electric trams. This transition was marked by the Tokyo Basha Tetsudo (‘horse carriage’) railway’s conversion to electric power in 1903, becoming Tokyo Densha Tetsudo, with full electrification achieved by 1904. The city’s acquisition of the private tram (or streetcar) company in 1911, forming Tokyo Shiden (“city electric”), further solidified the electric tram network.

Note, however, that the Japanese word densha (“electric” + “car/carriage”) remained consistent throughout these changes, encompassing both trams and trains. In 1907, while electric trams served the inner city along street routes, incorporating significant stops like those near the imperial moat and Hibiya Park, the area Jibun walks through after buying the book, at the beginning of The Innocent.

This map shows the electric tram and train system of Tokyo in 1911. The circular red web in the middle comprises tram lines that follow street routes in central Tokyo: they radiate out from the Imperial Palace, whose moats are drawn in blue. In Chapter 1, Jibun walks around the south east corner of this complex (Hibiya Moat) to Hibiya Park. In 1911 the Kobu line is denoted as the Chuo line and runs from Kandabashi through Shinjuku and west to Nakano, where Jibun travels.

Several rail lines connecting more distant areas were under development. These included the Kōbu Railway, which later became part of today’s important Chuo Line. This line, serving western suburbs, had stations at Okubo, Yotsuya and Nakano, where Jibun travels to see his friend. This distinction between trams and trains is crucial for understanding the novella’s setting. In Chapter 7, Jibun provides a street address for a rail stop, a clear indicator that technically he’s using a tram, and not a train.

It’s important to remember that early densha, whether trams or trains, were often single carriages, much like trams. Thus, the physical form didn’t drastically change in the public consciousness.

The photo shows precisely the model of densha that Jibun rides on the Kobu line — a 10-meter-long, four-wheel-car imported from England and used subsequently as trains by Japanese National Railways

The modern understanding of ‘train,’ with its etymological connotation of ‘a series of things drawn along behind,’ can be misleading. This is particularly relevant when considering the Kobu Line, which used electric ‘densha’ to connect suburbs to central Tokyo, and therefore could be considered a train, but was not the modern multi-car train. At the same, the station described in Chapter 3, with Jibun catching the Kobu line and alighting with Tsuru at Okubo, the platform, gates, and exit route are clearly more substantial than a neighbourhood tram stop.

Given the nuance of translating the word densha and the potential for misinterpretation, I’ve chosen to use “tram” in some places when referring to the Kobu Line. This decision is based on several factors: First, the physical form of the early electric densha closely resembled trams, particularly in their single-carriage configuration. Second, the term “tram” helps to differentiate these early suburban rail services from the modern concept of a multi-carriage “train.” Third, the use of “tram” allows for a more consistent and accessible reading experience, particularly for readers unfamiliar with the nuances of early 20th-century Japanese rail transport.

While acknowledging the technical distinction between the Kobu Line as a railway and the city’s tram network, my aim is to convey the historical context and the lived experience of the characters as accurately as possible. The use of ‘tram’ in specific instances is a deliberate choice to bridge the gap between the historical reality and the modern reader’s understanding, aiming for a setting that accommodates the action authentically and accessibly. Admittedly, it should be possible to adjust future iterations of The Innocent to clarify the point I have indicated here.

Michael Guest © 2025

Notes and further reading

Saneatsu Mushanokoji, The Innocent (1911), trans. Michael Guest, Sydney: Furin Chime Press, 2024.

- geta: Japanese footwear, consisting of a wooden base held on by fabric straps, similar to ‘thongs’ or ‘flipflops’. They may be elevated by one or two so-called ‘teeth’. or wooden blocks.

- koma-geta: a style of geta with low teeth.

- seventeenth day of [the moon’s] cycle: Known as Tachimachizuki (‘standing and waiting’). As the moon rises progressively later during this phase, one has to ‘stand and wait’ for it to appear. See Rikumo Journal.

Aitken, Annika (2023). ‘Interpreting Shunga Scroll: sex and desire between women in Edo’s ‘floating world’

Bureau of Urban Development, Tokyo. The Changing Face of Tokyo: From Edo to Today, and into the Future

Mochizuki, Yoshijiro (2005). Rediscovering Musha-ism: The Theory of Happiness in the Early Works of Saneatsu Mushakoji, MA Thesis, University of Hawaii. PDF from U of Hawaii.

Okazaki, Y (compiler) (1955).Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era: Japanese Literature in the Meiji Era (Published by Toyo Bunko: one of the world’s five largest Eastern Studies libraries).

Shields, James Mark (2018). “Future Perfect: Tolstoy and the Structures of Agrarian-Buddhist Utopianism in Taishō Japan,” Religions 9 (5), 161. HTML or PDF

Suzuki, T (1955). Narrating the Self: Fictions of Japanese Modernity (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford UP)

English translation of Saneatsu Mushanokoji’s The Innocent (1911) by Michael Guest © 2024