Willie will need to prove his mettle. He is well in the running to become Cambridge University’s Senior Wrangler for the year: referring to the highest scoring third year first-class honours student in the Mathematical Tripos. An amazing feat for a farm lad, but Willie is worn out with study, his brain over-taxed, and the Tripos commences today!

The Mathematical Tripos was a formidable examination taken by students after three years and one term at the University […] For example, in 1854, the Tripos consisted of 16 papers, 2 papers each day for 8 days — a total of 44.5 hours in the examination room. The total number of questions set was 211. (Forfar)

That’s the least of it. What will he do if he discovers that his betrothed, his beloved Lady Kate Kepple, has been abducted by murderous thugs on her way home from the opera? His uncle, Lawyer Whiston, seems reluctant to pass on the news. It would be sure to distract the boy! Undoubtedly receptive to Smith’s reveries on the transcendent power of Love, the reader has a reasonable idea that Willie is more likely to send the Tripos to the devil, for the sake of his Kate.

Since 1910, the rankings have not been made public (within the general scheme: Wranglers, first-class honours; Senior Optimes, second-class; Junior Optimes, third-class). For the hundred and fifty-odd years prior, results were proclaimed far and wide, and supreme prestige afforded to the Senior Wrangler. Indeed, to become Senior Wrangler in the Mathematical Tripos was considered the highest intellectual achievement in the country.

He’d be assured of a place among the highest ranks, such as in the church, legal, actuarian, medical or political professions. Lawyer Whiston already regards Willie as the stuff “of which lord chancellors, statesmen, and prime ministers are made” (Chapter 23).

The situations of plot, along with the romantic themes, dovetail with seemingly more bookish political issues. What do you have to do to get the wheels of the Home Office turning, even in such a dire emergency as ours?

Sir George has it right in one. The country is going to the dogs. The system is weighed down, clogged up with indolent “Tory place-men” — let alone the stultifying effects that descend from an idiotic, indulgent regent. It’s like a fish rotting from the head down.

An old, mad, blind, despised, and dying King;

Princes, the dregs of their dull race, who flow

Through public scorn,—mud from a muddy spring;(from “England in 1819” by Percy Bysshe Shelley)

Thus the narrator’s description of Beacham’s yacht comments on the condition of the metaphorical “ship of state”:

Everything appeared in confusion; rigging incomplete; cabin windows out of place; paint half dry; the decks encumbered with canvas, tools and litter.

The British system (of decades earlier than the writing of the novel) cries out to be rectified: in need of upright, honest, rational, selfless action. Youth holds the ultimate key: youth such as Willie’s, who points the way to a society governed by ethics, intelligence and merit.

Hence Smith’s heavy irony in alluding to the “irreligious, revolutionary, insane” new call for reform. Writing from several decades in the future, Smith has the benefit of 20/20 historical hindsight. Here we are yet six or so years prior to the Peterloo Massacre of 1819, a deadly cavalry charge upon a crowd of up to 80,000 peaceful protesters demanding reform of parliamentary representation.

The event fuelled a radical movement leading to the Reform Acts of 1832, 1867 and 1884, by which the right to vote gradually expanded, descending the class ladder.

Smith’s story is not so politically charged in itself. Rather, his strategy is to reaffirm democratic values to a readership in whom they are already entrenched. His historico-political allusions may be understood as an ingenious method of reeling in the reader, by subtly invoking a sympathetic ideology of the status quo.

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

Great Surprise both in London and Cambridge — Honours Rejected — Flight of a Senior Wrangler — Preparations to Explore the Bitterns’ Marsh

As may well be supposed, there was a great commotion in London when the abduction of the fair cousins became known. Many persons refused to believe it. ‘Absurd! Impossible!’ they said. ‘Two young ladies carried off in the heart of the most civilised, best governed city in the world! Ridiculous!’ Others shook their heads, looked exceedingly knowing, and whispered something about a double elopement. What seemed to give a shadow of probability to the last surmise was that no trace of the lost ones had been discovered, although Sir George Meredith and Lord Bury had set the Home Office magistrates and detectives on the alert. Hand-bills, offering a very large reward, had been placarded, not only throughout Westminster, but the business parts of the city. Many a hungry wretch, on keen scent for a breakfast or a dinner, possibly for both meals in one, scratched his ears and wondered if he could not make something out of them. Detectives looked grave, perfectly speechless mysteries; not even that enterprising race, the reporters, could extract a word from them.

The truth was, they had nothing to tell.

Lady Montague, not knowing what better to do, had sent for her solicitor — a proceeding quite as sensible, if not a little more so, than the others.

The old lawyer listened to her tale with such evident dismay that it increased the terror of his client. His countenance, usually so impassible, became deadly pale, and as he clasped his hands together he murmured:

‘My boy! my poor boy! it will kill him! And this is examination day! Such hopes as his tutors wrote me.’

In all the difficulties of life, from which neither rank, wealth, nor virtue are exempt, her ladyship had eventually found consolation in the ready suggestions and sound common sense with which her legal adviser encountered them; but now he sat speechless; not a word of consolation or counsel to offer. All he did was to repeat the words, ‘My poor boy!’

‘What are we to do?’ exclaimed the aunt, looking in his face with almost childish confidence. ‘My nieces must be found, and the wretches punished.’

‘They will be found — no fear of that,’ replied Mr. Whiston, who began slowly to recover his self-possession, ‘and the authors of the outrage punished. The question is,’ he added, and the tone in which he uttered the words imparted a fearful meaning to them, ‘What shall we have to punish?’

Lady Montague hid her face with her hands and sobbed hysterically.

The lawyer returned to his office, where he remained for several hours buried in deep reflection. His plans at last were laid; and when he issued forth, he appeared cool and collected as ever — astonished his old coachman, and no doubt the horses, by the rapidity with which he drove from public office to office. His last visit was to Westminster Hall, where he had a long interview with the lord chancellor.

When he quitted the presence of that important functionary, an officer of his court accompanied him.

On reaching his offices he found Sir George Meredith and Lord Bury impatiently awaiting his return.

‘No time for words!’ he exclaimed; ‘every instant must be employed in action.’

‘Ought we not,’ demanded the distracted lover of Clara, ‘to dispatch officers to all the nearest seaports?’

‘Done three hours since, my lord,’ was the reply.

‘Increase the reward,’ suggested the father.

‘Loss of time, Sir George.’

‘Apply again at the Home Office?’

‘The Home Office be ——’ As the speaker was unquestionably a moral man, we trust he only said ‘hanged.’ At any rate the word sounded very like it. ‘Been there myself. Saw the minister. An empty-pated idiot told me to prepare a statement on oath! Statements and oaths in such a case! High time we had reform. Shall vote for it next election. Heaven knows we want it!’

Under less exciting circumstances his hearers would have been inexpressibly shocked by this favourable allusion to the irreligious, revolutionary, insane cry for reform just beginning to make itself heard and shaking the ranks of Tory place-men. A few plain, sensible men were just beginning to suspect the hollow tinsel they had so long taken for pure gold, and, what was worse, to analyse it. They had discovered a vast amount of base metal already.

The door of the private office was opened very gently, and the managing clerk made his appearance with a half-hesitating air as if he did not feel quite certain what kind of a reception he would meet with. In his hand he held a scrap of dirty paper, folded in the shape of a letter. With the rapidity of a hawk darting on a sparrow his employer pounced upon it, and tore open the wafer, which contained but three words: ‘Bittern’s Marsh. Bunce.’

‘Thank God!’ ejaculated Mr. Whiston, as he sank back in his chair, letting the paper drop from his hand.

It was no time for ceremony. Lord Bury picked it up, and read them aloud.

‘Still, I do not understand,’ he said. ‘Where is the Bittern’s Marsh?’

‘A tract of land upon the Essex coast, inhabited by the worst of characters,’ replied the lawyer. ‘It belongs to your father, Viscount Allworth. Lady Kate and her cousin have been conveyed there.’

The marked emphasis which the speaker placed upon the word father brought a blush of indignation to the face of the son.

‘Can you rely upon the information?’ demanded the baronet.

‘Implicitly.’

‘The integrity of the writer?’

‘As on my own; more so,’ replied Mr. Whiston, ‘for he has resisted temptations to which, thank Heaven, I have never been exposed.’

Lord Bury said something about seeing his father.

‘Do nothing of the kind,’ continued the former. ‘This scrap of paper has given the only clue that was wanted; changed surmise to certainty. It would put the plotters upon their guard. The girls, I can answer for it, have one devoted friend hovering near them. O! If I had but a yacht at my disposal!’

The baronet suggested an application to the admiralty; but the lawyer at once pooh-poohed it. He had quite experience enough of public officers and red tape officials. Egbert proposed something more practical. His friend Beacham’s yacht, he said, was lying at St. Catherine’s Dock for repairs; it must be ready by this time, and was at his disposal.

‘Still more delay!’ groaned the baronet.

‘It is the best we can do,’ observed the nephew, mournfully.

‘We must see to it at once,’ exclaimed the lawyer; ‘better trust to that than to official interference. Talk of the law’s delay! Nothing, compared with it. It should be well manned.’

‘Leave that to me,’ replied his lordship. ‘Eight or ten men of my own troop are stationed at Whitehall, recruiting; not one of them but will follow me. Tom Randal, just named cadet at the Veterinary College, came to town with me this morning.’

‘God bless you, my dear boy!’ said the father of Clara, wringing his hand. ‘You know what we are struggling for.’

He could say no more.

His nephew not only knew, but felt it. An extraordinary change had taken place in him; he began to see the world — all that is worthless, all that is estimable in it — as it really is; not as false education, pride of birth, as the prejudices of society had painted it. The indifference, languid apathy which, in fashionable parlance, nothing less than an earthquake ought to have shaken, suddenly disappeared. The man had replaced the club-lounger; he was all life and energy. The soil must originally have been good; but the weeds had hitherto choked it.

Never again rail against true, honest love, no matter what the conditions or inequalities; it is the surest test of the true metal. Gold is as frequently mistake for pinchbeck by the unthinking as pinchbeck is for gold.

On their arrival at St. Catherine’s Dock the rescuers hastened on board the Leander — the name of Beacham’s yacht — where a cruel disappointment awaited them. Everything appeared in confusion; rigging incomplete; cabin windows out of place; paint half dry; the decks encumbered with canvas, tools and litter.

Sir George Meredith and his lordship began to remonstrate, explain, argue, and propose all kinds of practicable and impracticable schemes. Here it was that the practical common sense of Richard Whiston came to their assistance. Calling the master-shipwright to the front, he said:

‘The Leander must leave the dock in twenty-four hours.’

‘Impossible,’ was the reply.

‘Don’t understand the word; it is only a crutch for lame fools to hobble upon. Whose men are these?’ added the speaker, pointing to the shipwrights.

‘Searle’s, sir.’

‘The word, then, was doubly absurd,’ continued the lawyer. ‘Searles’s men can do anything.’

This last touch flattered their pride, and the carpenters began to grin.

The speaker drew forth his watch. It was just four o’clock.

‘Hear me,’ added the speaker.’ If by this hour to-morrow the Leander is in the river in navigable order —never mind the painting, gilding, and fine work — Lord Bury, Sir George Meredith, and myself will distribute the sum of one thousand pounds amongst the honest fellows who execute our wishes.’

The men gave a hearty cheer.

‘Never mind that,’ said Mr. Whiston. ‘It is a hard task I have set you; but the recompense is a noble one, remember. One thousand pounds. To work at once. Strong hands and willing hearts can accomplish everything. You have lost five minutes already.’

‘Is this offer really a serious one?’ inquired the master-carpenter.

‘Serious as the Bank of England, and payable as its notes for value received,’ remarked the lawyer.

‘Then,’ exclaimed several of the men, ‘it shall be done if muscle and good will can do it. To work, lads, to work.’

As Lawyer Whiston remarked, somewhat bitterly, when he heard of the abduction of the cousins, it was examination day at Cambridge — the first of the three which annually decide who are to be the winners of the great prizes which the university holds out to the ambition of aspiring youth — the senior wranglership and the head of the classical tripos. Should intelligence of the outrage reach William he trembled for the result, the reaction upon his over-taxed brain’ for his studies had been severe.

The senior wranglership opens the door to fame, fortune, and distinctions of every kind, but only a little way. The holder has still years of toil before him ere the mitre of the bishop, the ermined mantle of the judge, and the influence of the statesman fall within his reach. Still it clears the way. He is already a marked man. His future career is curiously watched. The public mind has taken hold of him; he is a possibility of the future and rarely forgotten.

The head of the tripos enjoys similar advantages, but in a less eminent degree.

The first day’s examination had closed, and our hero retired to his rooms in glorious old Trinity. Poor fellow, he looked pale, worn by hard brainwork and excitement. It was the future that stared him in the face. No wonder the vision startled him.

His papers, written under the eyes of the examiners, had proved most brilliant. College Dons had smiled upon him, the vice-chancellor given him a friendly nod as he quitted the senate-house, and advised him to take care of himself. No wonder his rooms were crowded. Friends anticipated his triumph — rivals feared it. It was seven in the evening before he found himself alone, alone with proud and happy thoughts, the prospect of success honestly won.

‘Should it be so,’ he murmured to himself, ‘dear Kate may be pardoned for her choice, although it still leaves me unworthy of such a blessing.’

His gyp — college servant — now made his appearance and informed his master that his dinner would be ready in a few minutes. The poor fellow had an air of unusual respect and importance. He, too, had heard of the general impression, and the shadow of Willie’s future greatness had fallen upon him. He was not very ambitious; his dreams extended no further than bearing the train of some future chief justice, or possibly lord chancellor, in the house of peers.

‘Eat it yourself, Gibby,’ said. the tired student. ‘All I require is a cup of strong tea and a biscuit.’

‘Certainly, my lord!’

Our hero smiled; he read the speaker’s thoughts.

‘What is that you have in your hand?’ he asked.

‘The London paper, my — h’m, sir, I meant to say. Third edition. Great sensation. I have only just glanced at it. But nothing ‘like one,’ he added slyly, ‘that will appear in a day or two.’

The gyp alluded to the result of the examinations.

‘Leave it with me,’ said William. Anything to cool my heated brain and change the current of my thoughts.’

The speaker had been engaged in the columns but a few minutes when, with a cry that must have come from his heart, he sprang from the chair. In the pages of the Post he had read an account of the abduction of Lady Kate and her cousin. The names were not given in full, but his love divined them. In an instant his mind was made up, his course decided upon. What were the honours which awaited him, the triumph over his competitors, several of whom had affected to look down upon the farmer’s boy, as they insolently termed him, or the gratification of his own legitimate ambition! All vanished at the call of manhood, the claims of true affection. He would have been unworthy the love of a true woman had he hesitated. Within an hour he left the university, its honours, pledges of future fame behind him; left them without one sigh of regret. A nobler and far more imperious call decided him — love, the beacon light, the polar star of man’s existence, guiding him to happiness or misery as virtue or vice inspire him. Love! How often, in our more youthful days, have we tried to analyse the passion. Reason cannot grasp it, nor retort or alembic hold it for one instant. It is more subtle than the subtlest essence. In short, so incomprehensible that he who bestowed the God-like faculties upon the beings he created alone can comprehend it.

The grey-eyed moon was faintly gilding the roofs and quaint gables of the old-fashioned farmhouses scattered round Deerhurst, and the Widow Gob, despite her sixty years, was busily engaged in preparing breakfast for her son, herself, and the labourers. She was, as might be expected in the mother of a young giant like Goliah, a strong and rather muscular-looking woman. Honest labour had made her so. She made excellent butter and cheese, saw to the work with her own eyes, helped it with her own hands. A rude but cleanly abundance reigned throughout her house. Mrs. Gob did not understand makeshifts. If she kept rather a tight hand upon worldly gear, it was not through avarice. She loved her big boy very dearly, and it was for him that she saved.

‘God bless us!’ exclaimed the widow, as a post-chaise, the horses flecked with foam, drove up to the door. ‘Who can this be? Company? Only brown bread, bacon and eggs for breakfast, too.’

Our hero — we still persist in calling him so — alighted, so haggard, broken down, and careworn in appearance that at first she scarcely recognised him.

‘Why, Willie,’ she said, at last, after taking a good stare at him, ‘be that really you?’

‘Where is Goliah?’ asked the exhausted traveller.

‘In the home croft.’

The worn-out student attempted to rise from the oaken settle on which he had sank.

‘Sit thee still,’ added the speaker. ‘I can tell him.’

Going to the door, she placed her hand to her mouth and sent up a shout that might have been heard at — but as we pride ourselves on our veracity, we will not name the distance. It proved one thing better even than the stethoscope could have done, that the widow’s lungs were in a remarkably healthy condition.

In a few minutes her son came rushing into the kitchen.

‘God save us, mother!’ he exclaimed. ‘Be the chimbly afire?’

Mrs. Gob pointed to their visitor.

The eyes of friendship, like those of love, are exceedingly keen. Goliah knew him in an instant, and taking the thin, white hands of our hero in his own, gazed on the piteous features with the piteous look of patient fidelity so noticeable in the hound when the master is ill.

‘Willie! dear Willie!’ he said, and his voice became wondrously gentle, ‘what be the matter on thee? What ha’ they done to thee? That cussed varsity and them books be akillin’ on thee.’

‘It is not that — not that,’ replied his friend, with a faint smile.

‘What be it then?’

‘The world will think I have acted very foolishly,’ added the former, ‘but I shall never regret it, for my heart tells me I am right.’

‘And I’ll swear to it!’ exclaimed the honest rustic, slapping his thigh — a way he had when excited. ‘Swear to it,’ her repeated, ‘on any book, and afore all the lawyers and justices in England. So let us hear all about it.’

Perceiving, or fancying that he did so, a slight degree of hesitation on the part of William Whiston to explain matters in the presence of his mother, the speaker turned to that excellent personage and asked if she could not broil them a chicken.

‘Two, my boys,’ said the widow, as she walked from the kitchen, ‘if you and Willie can eat them.’

Did Mrs. Gob listen to the conversation that ensued? We almost fear she did — mind, we do not assert it. Mothers have strange privileges, and singular modes of exercising them. When she returned in something less than an hour’s time, bearing the savoury dish in her hands, her countenance appeared hard set — not with anger, but resolution — like that of a person prepared to meet a stern necessity.

‘I cannot eat,’ said our hero, turning from the table, after swallowing one or two mouthfuls. ‘My heart revolts at the thought of food.’

‘An’ I beant hungry,’ observed his friend, who had already devoured at least half of one of the fowls. ‘My heart, too, do feel uncommon heavy.’

Poor fellow! He was thinking of Susan.

‘You must eat, both of you,’ observed the widow, firmly. ‘How else will you find strength to encounter the dangers and fatigues of the Bittern’s Marsh?’

The young men exchanged a glance of surprise.

Decidedly the speaker must have listened. Goliah did not seem so much astonished as his friend; but, then, he was her son.

‘Why, what put that in your head?’ he began.

‘No frimicating’ — which in the dialect of the eastern counties means affectation, or pretence — interrupted the widow. ‘Yer can’t deceive me; no reason why yer should. Ain’t I yer mother? Did yer think l’d sit still and patiently see my own boy, to say nothing of poor Willie, robbed of the girls they love? Not if I know it! Yer must eat, I tell yer, and take some rest, too, for it would be foolhardy to venture into the Marsh before nightfall, where you will need all your strength and courage.’

Our hero groaned with impatience.

‘She is right,’ whispered his friend. Turning to the widow, he added: ‘Do yer really mean what yer say?’

‘Bring back Susan safe to Deerhurst,’ said his mother, with a faint smile, ‘and I will answer that question.’

Goliah started from his seat, threw his arms round the speaker’s neck, and imprinted a kiss upon her still comely cheek — a kiss such as no doubt would have greatly shocked the Misses Prue and Prim of the present day.

‘She be a good girl,’ added the widow, after settling her cap; old women wore caps in those days. ‘I’ve had my eyes on her and on you, too. Yer thought I was blind, I suppose. Lord! Lord! how simple these boys and gals all be!’

The kind-hearted woman had her own way. Convinced at last of the folly — we might say madness — of attempting to penetrate the Bittern’s Marsh in broad daylight, William Whiston reluctantly consented to take a few hours’ repose.

‘Be it so,’ he said. ‘Rest for the body, not for the mind.’

He was mistaken. Mrs. Gob was not only a good housekeeper, but, like most farmers’ wives, possessed some skill in the use of simples. Preparing a draught with her own hands of herbs gathered on the farm, she prevailed on the youth to take it. He slept so long and soundly that the shades of evening were gathering around Deerhurst when he awoke.

Meanwhile, everything, had been prepared for the departure of the friends — garrets ransacked for old clothes to disguise them in, money in separate purses, lest they should be separated. The widow had thought of everything, even to the name of an old servant of hers who had been wheedled into marrying a handsome, good looking scamp, and finally settled in the marsh with him.

Her mistress had frequently assisted her in her distresses.

The last thing Mrs. Gob placed in the hands of her son were his father’s pistols. She had cleaned and loaded them herself, and looked exceedingly pale as she gave them.

‘Only in self-defence,’ she whispered. ‘And, O! Goliah, remember you have a mother! But do your duty,’ she added. ‘Don’t forget that you are a man!’

The Spartan matron’s words to her soldier boy, when she gave him his shield on the eve of battle, ‘With it, or on it,’ were much more poetical perhaps, but not so true to nature.

It was not till ‘the boys,’ as she called them, had quitted the farm, and the last echo of their footsteps died away, that the widow found her courage fail her.

And then she cried bitterly. Her tears were for the safety of her son.

The Spartan mother would have smiled upon his corpse. But, then, Mrs. Gob was not a Spartan.

This edition © 2020 Furin Chime, Michael Guest

Notes, References and Further Reading

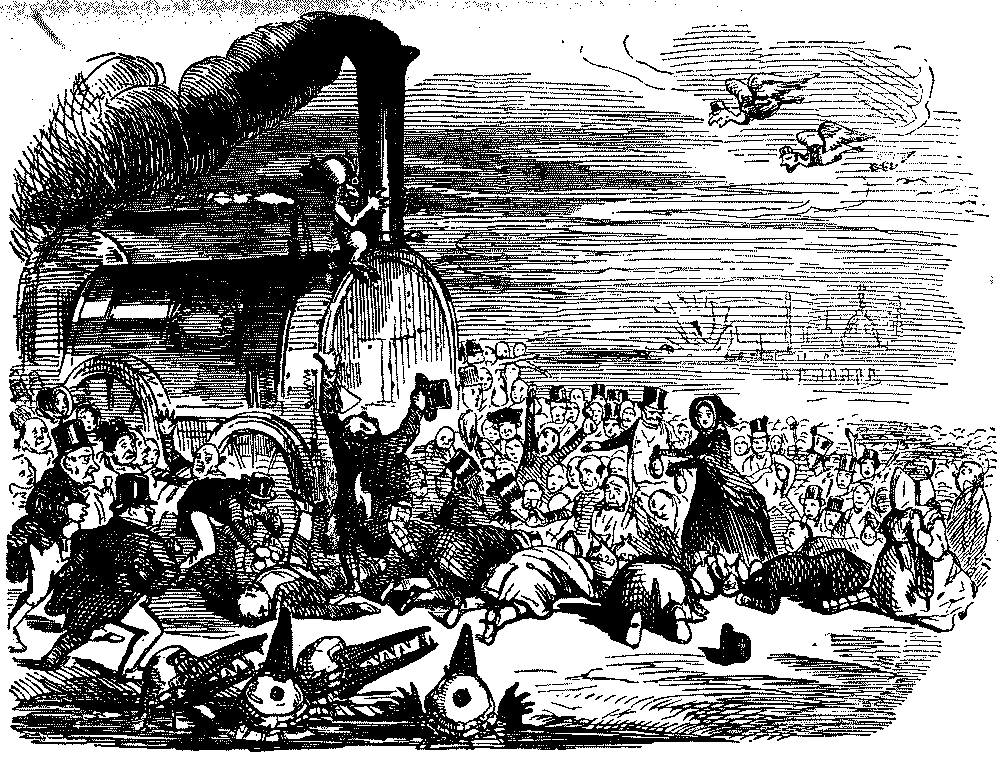

- Image: Admission of the Senior Wrangler in 1842: Scanned from H P Stokes, Ceremonies of the University of Cambridge, CUP 1927.

- Here is a question of the sort for which Willie is preparing himself:

- placeman: “chiefly British, often disparaging: a political appointee to a public office especially in 18th century Britain.” Merriam-Webster.

- alembic: “An alembic (الإنبيق, al-inbīq); Ancient Greek: ἄμβιξ (ambix, ‘cup, beaker’): an alchemical still consisting of two vessels connected by a tube, used for distilling.” Wikipedia

- frimicating: Goliah’s favourite F-word. E.g., Chapters 1, 3, etc. See external definition in Chapter 13 (n).

- simples: Interesting connection with Nance, the wise woman of the Bitterns’ Marsh. See Chapter 19 (n) for definition.

- Photo of rural woman at pump: “The costume of country women lagged behind that of town dwellers until the middle of the nineteenth century when simplified versions of more fashionable clothes were increasingly adopted. For the poor, new clothes were often hand-made at home with cloth bought from both local shops and travelling salesmen. A large trade in second hand, and even third and fourth hand, clothes existed during this period. The wives and daughters of prosperous farmers however, sought as fashionable clothes as they could find. From the turn of the twentieth century the distinction between rural and town costume had virtually disappeared and country women dressed to suit their personal taste and what their pockets could afford. The country woman pictured is wearing a waist apron and a sun bonnet. Such bonnets were particularly popular between 1840 and 1914” (Museum of English Rural Life, University of Reading).

*Forfar, D.O. “What became of the Senior Wranglers?” Amended version of article first published in Mathematical Spectrum Vol. 29 No. 1, 1996. Jump to PDF.

*Galton, F. “Hereditary Genius: an inquiry into its laws and consequences” (1869). Fascinating research based on Cambridge Wranglers. Jump to PDF.

*Mandler, P. (ed.) Liberty and Authority in Victorian Britain. Oxford: OUP, 2006.

Evert, G. “The Reform Acts” Victorian Web.

Briggs, A. “Reforming Acts.” BBC, archived.

“Introduction to Georgian England (1714-1837).” English Heritage.

*”Dare to be free: Revolt and Reform in Regency England.” Warwick U Library. Contemporary facsimile pamphlets, etc. Jump to webpage.

*”Reform!!! or The House that Jack Built”. Warwick Digital Collections. Jump to Webpage.