We arrive at last at the denouement. The term is borrowed from the French dénouement, Aristotle’s Poetics first having made its way into English via André Dacier’s 1692 French translation, Poëtique d’Aristote Traduite en François avec des Remarques. In Aristotle’s Art of Poetry (1705) Theodore Goulston translates dénouement as “unravelling“:

Over the next few decades, the English word “unravelling” — plainly descriptive as it is — was supplanted by the alluring, intellectual-sounding French term. “Denouement” does assume a sense of specificity as a technical term, which would have been clouded in the humble “unravelling.”

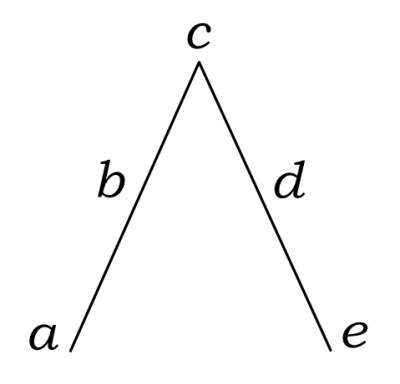

Moreover, the root of the French word, nouer, “to tie” or “to knot”, from the Latin nodus, “a knot” (Merriam-Webster) implies the untying of a knot that was in the first place deliberately tied. Thus it is apropos to narrative form, in which plots become increasingly complicated in their movement, until something disturbs the “upward” momentum, and there is a turning point and descent.

As a technical term in drama, denouement is considered a synonym for the Aristotelian “catastrophe,” which is derived from katá, “down, against” + stréphō, “I turn” (Wiktionary) — that is, a down-turning or unwinding of the story (once it has been wound up, so to speak). This aesthetic usage is distinguished from the everyday sense of a “terrible happening”; though it’s easy to deduce its derivation from classical tragedy.

Turning now to Smith’s denouement, we can only marvel at the masterly hand with which he effects the final unravelling of Mystery of the Marsh. His engaging light touch, his wit and refinement are in evidence throughout.

As ever, social currents bubble beneath, with all the qualities of splendour, subtlety, and crassness that characterize not only Regency society, perhaps, but all the human race. Legal strategies and points of moral principle are teased out and resolved. Character nuances are polished to a tasteful finish (note Bury’s absolute redemption from his conditioned class prejudice). The i’s are dotted and t’s elegantly crossed.

On the entrance of the villains, we feel we have to stop ourselves from hissing out loud. Just deserts are meted out in fine measure. Loose threads are tied, the abject truth and consequence of corrupt relationships revealed.

Vaguely remembered sub-plots are recalled. “Bet you’d forgotten about that one …” Smith seems to say with a chuckle at your expense — “Well, I hadn’t!” And his fine touch with the technique of reader-address, with which the reader has become quite familiar, seems now at once quaint and profound, evidencing an awareness of an intimate fellowship. He won’t tell a secret straight out, but “we suspect our readers have a shrewd guess at it.”

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

An Unexpected Surprise, Followed by a Monster Law Suit — Conclusion — The Running Down of the Clock — Its Last Tick

The next morning the fashionable portion of London was greatly agitated by the various reports which appeared in the morning papers. Scarcely one gave a correct version of the affair. The names of the fair cousins were no longer masked by initials — transparent to all who recollected the previous reports — but were printed at full length.

Lady Montague had a fit of the horrors. Lord Bury looked serious, and Sir George Meredith felt so indignant at the outrage offered to his child that he threatened to go over at once to the Liberals unless the Home Office did prompt justice to his demands. Having fully made up his mind, and satisfied as to the conclusion, he did as many hasty, well-meaning persons do on similar occasions: he sent for his lawyer to draw up his memorial.

Mr. Whiston expected the summons, and was speedily in attendance. He listened to his statements with exemplary patience, as he did to all his clients when they were angry, and then pronounced emphatically against the step.

‘You must apply to the chancellor,’ he said.

‘For once you are wrong,’ exclaimed the baronet. ‘Clara is not a ward in chancery.’

‘But Lady Kate is,’ observed the man of law. ‘The cases are the same; both lie in a nutshell; you cannot separate them.’

‘Still I do not see how his lordship’s power hears upon the point.’

The lawyer gave him a pitying smile.

‘His power bears upon every point that comes before his court,’ he said; ‘practically it is illimitable — has never been defined. What he cannot do I have not the slightest idea; but I will tell you what he will do — issue an order to the Home Office to dispatch a body of well-armed officers to the Bittern’s Marsh, with powers to arrest every living actor in the outrage they may discover, and bring back the bodies of the dead ones.’

‘Why, then there will be an inquest!’

‘I trust so.’

‘Trust so?’ repeated Sir George. ‘Would you kill my child?’

Mr. Whiston appeared slightly moved.

‘I am not a father,’ he observed; ‘but I can feel for your embarrassment. Would you have the reputation of two pure, innocent girls exposed to the sneers of slander — the covert doubts, the half-veiled suspicion, whose stings are worse than death? No; their purity must be established by the light of judicial inquiry; by legal evidence, without a flaw for malice to hang a rumor on. It will be a hard trial for them; but it must be endured. I see no other way.’

Sir George Meredith paced the room for some time in silence. Much as he disliked publicity, his better judgment at last prevailed.

‘You are right,’ he said; ‘a hundred times right. I must prepare my daughter for the ordeal; but who shall prepare my niece?’

The lawyer smiled.

‘Girls,’ he observed, ‘are stronger than we deem. Their own virtue and the dawning prospect of future happiness will sustain them. Leave the rest to me. I will instantly prepare a memorial to his lordship, and feel no doubt as to the result.’

On his return home, whilst still relating the conversation to his nephew, Lord Bury was announced. Without noticing the lawyer, the young nobleman walked directly up to our hero and extended his hand. It was the first time he had ever done so.

‘Mr. William Whiston,’ he said, ‘I have heard of the noble sacrifice you have made to affection and true manhood. I, for one, am prepared to welcome most cordially your alliance with my cousin. At the request of my aunt, I add that she will be most happy to receive you at Montague House as the acknowledged suitor of her niece.’

Our hero grasped the hand extended to him most cordially.

‘My dear lord —’ he said.

‘Had we not better call each other by our Christian names now, since we are likely to become so nearly related? Let it be henceforth William and Egbert between us.’

‘If you really wish it.’

‘I do wish it,’ replied the visitor, energetically. ‘The last few weeks have taught me more than one lesson — that man’s true nobility is in himself, not in the accident of birth. My greatest desire is to prove worthy of your esteem.’

On that day the speaker made two fast friends — the nephew and his uncle. The latter proved a most important one. He divined, if he did not exactly know, the exact position his father’s conduct had placed him in, and mentally resolved to exert all his skill and experience to extricate him.

The legal step turned out exactly as Lawyer Whiston predicted. The chancellor issued his rescript to the Home Office, and in three days the officers returned, not with any living prisoners, but the bodies of Clarence Marsham and Burcham.

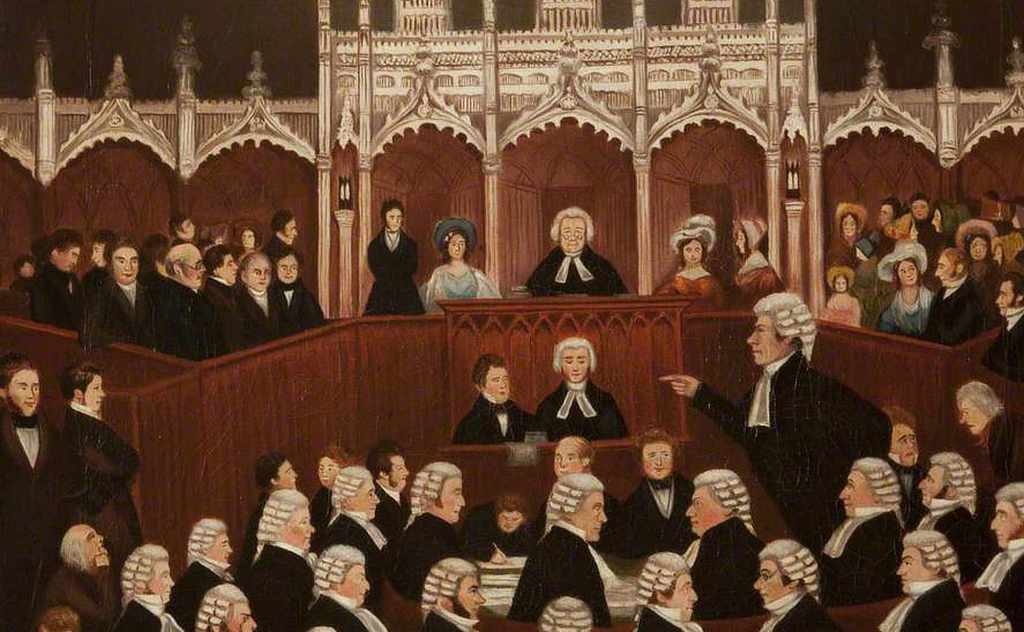

On the morning of the inquest the coroner’s court appeared unusually crowded. Fabulous sums were offered for seats long after there ceased to be standing room. Public curiosity was on the alert, and peeresses and ladies of fashion hastened to the scene as to the opera or some other exciting spectacle.

Expectation was at its height, when Lady Montague, looking wonderfully calm and collected, entered the courtroom, with Clara and Kate, and all three took their seats upon the bench reserved for them. The jury, having already been empaneled, had viewed the bodies in a room apart.

An array of men eminent at the bar appeared on both sides. The arch-plotter had taken care of her own interests; not even the death of her son could blind her to them.

We have neither time nor space to give the examinations of the witnesses. Lawyer Whiston had prepared the evidence on his side — the letters of Lady Allworth were read, which covered her with infamy, and every point in the part of the dark transaction she had planned was most clearly proved. The narrative of the two cousins, which was clearly although faintly given, began to excite a deep sympathy; but when Susan, in her artless, simple way, related the death of the old domestic, the frantic entreaties of Kate to her cousin to kill her rather than suffer her to be forced into a marriage she abhorred, the feeling became positive enthusiasm. The jury declared they were ready to give their verdict. This, however, the counsel Lawyer Whiston had employed, acting under his instructions, by no means would permit; they insisted that every witness should be heard. Bunce, Willie, and Goliah gave their testimony, described the siege, the ruse by which the conspirators had been defeated, down to the arrival of Sir George Meredith and Lord Bury. Lastly the correspondence of Viscountess Allworth with the schoolmaster was read. The opposing barristers threw up their briefs in disgust, and the last fangs of the serpent, slander, on which her ladyship relied, were effectually drawn. Then, and then only, was the verdict of justifiable homicide received. Hosts of friends thronged around the cruelly persecuted girls to congratulate them on their escape.

Then, and then only, was the wisdom of the old lawyer’s advice fully understood.

When fashionable society in England does take a fit of virtuous indignation it generally proves an exceedingly strong one. The following day the elite of London called to inscribe their names in the visiting book at Montague House, whilst not one single note of condolence was left at that of the woman who had lost her son, whose name was already stamped with the indelible brand of infamy. Still, the arch plotter bore a bold front. When her husband, disgusted at the exposure — not on account of its immorality, but failure — hinted at the propriety of retiring to the country, she haughtily refused.

Title and fortune still remained to her. She could still defy the world.

In the midst of the dispute, a letter from her lawyer, Brit, was brought to her. As she read it her cheek became pale for an instant, not longer, and then her courage returned.

‘You must accompany me,’ she said. Our agent, Blackmore, has been arrested in London, and will be examined before noon at the police office.’

‘Our agent?’ repeated his lordship.

‘Well, my agent, and your tenant, if you prefer the distinction. The old idiot has been caught, wandering amongst the old book-stalls near Drury Lane. I thought he had escaped.’

The viscount began to feel exceedingly uncomfortable. He remembered the lease of the Bittern’s Marsh.

‘You must bail him,’ added his wife.

This proved a little too much even for his lordship’s philosophy to bear.

‘Absurd!’ he ejaculated.

‘I tell you that you must,’ continued the lady. ‘My reputation is at stake.’

‘Bah! It is lost already.’

‘And your life!’ This rather startled her hearer.

‘Think you I am such a weak fool as to have trusted you without precaution?’ continued the speaker. ‘Your forgeries upon your son are in my hands. I deposited them in the Bank of England. Bury was quite willing enough to pay them, but I refused to accept the money. He will never lay perjury upon his soul to save a father he must despise.’

‘The monster!’ ejaculated the now thoroughly terrified man.

Whether he meant his wife or his son we cannot undertake to decide.

‘You know me at last,’ said her ladyship, coolly. ‘Take your choice.’

‘Certainly, my love,’ was the submissive reply. ‘I am quite willing to go with you.’

‘The degradation proved unavailing. On their arrival at the police office the formal gentleman in black was there before them. When bail was offered he objected to bail, produced the chancellor’s warrant committing the prisoner for contempt of court, and bore him triumphantly off to the King’s Bench Prison, There we must leave him for a while.

During the day Bury received a most piteous appeal from his parent, and rushed with it to the office of Mr. Whiston, who read it carefully, smiling as he did so.

‘Is it possible that you can find a source of mirth in my distress?’

‘Not so, my dear lord,’ answered the lawyer, kindly. ‘If I smiled, it was because I begin to see my way out of this sad difficulty.’

‘Is it possible? How?’

‘That is my secret. Lady Allworth is playing a very close game, but I think I hold the winning card in my hand. In five days the forgeries shall be in your hands.’

‘May I believe this happiness?’

‘If I live, yes. Nothing but death can cancel my promise. Now leave me. I have the work of twenty younger men to do.’

The old man did not miscalculate his task.

As a matter of observation, one enormous scandal is generally succeeded by another equally notorious. Society was again startled by the report that a suit had been commenced by a certain person styling himself Charles Marsham, against Lady Allworth, for the recovery of the estates bequeathed to her by her first husband, and that the chancellor had placed a distringas upon all the property. The rumour proved to be correct; but what struck those watching the affair was the singular fact that, although the most eminent council had been employed by the plaintiff, his solicitor was an obscure but rising young man, who had never been previously engaged on any important case. Curiosity, especially among the legal profession, was greatly excited. More than once Mr. Whiston was questioned by his friends and acquaintances in the law, but he professed the most profound ignorance of the affair — professional ignorance of course. Outsiders, as well as lawyers, understand what that means.

Trembling at the possibility of losing her ill-acquired wealth, of which she had made so vile a use, her ladyship rushed to consult her advisers, Brit and Son, who received her rather coolly. They could do nothing, they declared, without money, the account against their client being already so much larger than they could afford to lose.

‘Why, you do not believe in this absurd claim?’

The elder Brit replied that the absurdity had very little to do with it, and the law was painfully uncertain. The firm had met with losses lately.

His son re-echoed the opinion.

‘After all the money you have made of me?’

The gentlemen smiled. Hitherto they had looked upon their client as a shrewd woman. The simplicity of the remark surprised them.

Still they adhered to their resolution. The junior partner suggested an appeal to her husband.

Her ladyship shook her head. He was almost as much pushed for money as herself.

‘Your ladyship still holds the securities lodged in the bank,’ observed the senior partner, ‘and the money is there to redeem them. With twenty thousand pounds it would be easy to defeat this conspiracy.’

‘You believe it one, then ?’

‘No doubt of it,’ replied the firm.

‘And you could see the treacherous old hypocrite, Blackmore?’

‘Money will do anything.’

The love of greed prevailed over the thirst for revenge, and the guilty woman finally consented to follow their advice. The money was recovered, the notes stamped as paid, and, an hour afterwards delivered to Lawyer Whiston, who claimed them as Lord Bury’s agent, to whose irrepressible satisfaction that same day they were destroyed.

As soon as the cousins were sufficiently recovered to bear the journey the united family left London for Sir George Meredith’s seat in the eastern counties, near Chellston, soon to become the property, we suspect, of Lord Bury, who, with our hero, accompanied them. The party would have still been larger, but Lawyer Whiston declared it impossible for himself, Bunce, and Old Nance to quit town. They did not ask his reasons. Already they had divined a part of his secret, and we suspect our readers have a shrewd guess at it.

As for the Sawter boys and their mother, they were already provided for.

‘Fear not,’ added the old, man; ‘we shall be in time.’

‘In time for what?’ innocently demanded Kate.

An arch look from the uncle of Willie brought a blush into her cheek. She asked no further questions.

We are not going to inflict upon our readers a technical account of the great trial, which soon afterwards took place, but merely relate a few of the incidents.

Lady Allworth, a former pupil of Theophilus Blackmore, had created interest with her instructor by her intelligence and aptitude. By his influence she obtained a situation in the family of Mr. Marsham, whose wife dying shortly afterwards, first awakened her ambition. Her plans were artfully laid.

By the connivance of the Bath woman it was given out that his infant son was drowned, and universally believed. Such, however, was not the case. It was secretly conveyed to the martello tower, where the schoolmaster, reduced to poverty, had taken up his abode. His servant, Nance, nursed the boy. The mysterious way in which he had been brought there first excited her suspicions, and induced her to gather up the fragments of half-burnt letters which first excited the curiosity of the astute lawyer. The cynical confession of Theophilus Blackmore, that of the Bath woman and French maid, who were all in the plot, not only proved the identity of the boy, but established the facts which the correspondence of the viscountess, discovered in the old tower, still further confirmed.

After days of wrangling arguing by council on either side a decree was at last pronounced by which Charles Marsham — so long known as Bunce the tramp — was declared heir to his late lather’s landed estate.

Poor fellow! the change in fortune appeared to afford him but slight pleasure As he feelingly observed, when his benefactor congratulated him, he was alone in the world.

‘Not so,’ replied his friend. You have an uncle and an aunt — Walter Marsham and his sister Pen — who are anxious to claim you. It was their money that enabled me to search out the evidence and carry on the suit successfully.’

The speaker did not say how much of his own he had expended.

On learning the result of the trial Lady Allworth retired to her own room. Everything had failed — scheming, lying, and even perjury proved useless. They had left her a pauper as far as wealth was concerned. An empty title alone remained, and even that now appeared valueless.

‘The way of transgressors is hard.’

The next morning she was found dead in her bed.

Thanks to obliging doctors and a complaisant jury, a verdict of apoplexy was given, and the body buried by her husband in an obscure churchyard in the city — no one to mourn her, no herald’s pomp, no stone to mark the spot, which was soon forgotten.

The brief space that remains to us must be devoted to happier themes — to self-sacrifice rewarded by faithful love, to prejudice rooted from a nature naturally good.

But ere the final act which was to crown the day-dreams of the lovers was fixed by the fair cousins the reconciliation of Tom Randal with his father was brought about. The rough old farmer, who had known but little peace since the quarrel, sought the cottage of the pretty Phœbe, made the amende honorable, and ask her to become the wife of his soldier boy. The happy girl consented, and proved no dowerless bride; the gift of the Home Farm from Clara accompanied her to the altar.

Goliah and Susan were married at the same time, and started for Deerhurst.

Here we are but slightly anticipating. A respectable peace, or rather an armed neutrality, was patched up between the widows. Mrs. Hurst, according to her husband’s will, retired to her own cottage, whilst Goliah’s mother remained in her own homestead.

Poor Goliah felt so boisterously happy that there exists a tradition even to the present day that on one occasion he was known to have kissed his mother-in-law.

When Lawyer Whiston, accompanied by Bunce — we must call him so, if only for the last time — visited Chellston, both were warmly welcomed. If Lady Kate and Clara looked a little shy, it was, as Lady Montague observed, exceedingly proper. They knew what the visit portended.

The great day dawned at last. Our hero and Lord Bury became the happy husbands of the girls they had so honestly won — the best reward mankind can claim or love bestow.

In less than a year’s time the same party were assembled at the same place. Health, sweet peace of mind, and calm content beamed on the features of all. And as they sat beneath the trees in the park many an innocent jest went round and tale of the past was related.

Bunce caught the infection of the hour, and was soon seen walking at evening shade by the side of Martha.

It proved afterwards a match.

Our task is over. The weights of the clock are run down and the final tick is heard.

THE END.

Notes and References

- draw up his memorial: memorial = “A petition or representation made by one or more individuals to a legislative or other body. When such instrument is addressed to a court, it is called a petition.” thefreedictionary.com (legal section).

- rescript: official edict, decree or announcement.

- distringas: a writ commanding the sheriff to distrain a person by that person’s goods or chattels (Merriam-Webster).

- Laura Knight, Sundown (1947): Entirely out of period, but looking towards the future.

Goulston, Theodore. (1705). Aristotle’s Art of Poetry (London: Browne and Turner). Available at Internet Archive. Jump to document.