Some pointed remarks in this and recent chapters invite a cursory digression into the world of heraldry. Whether an art or a science as are variously asserted, it is an intriguing and complicated field with roots in the ancient past as well as tendrils — if in some ways tenuous ones — in the present.

First, a few words on the historical origin of the herald:

He was in the first place the messenger of war or peace between sovereigns; and of courtesy or defiance between knights. His functions further included the superintendence of trials by battles, jousts, tournaments […] When the bearing of hereditary armorial insignia became an established usage its supervision was in most European countries added to the other duties of the herald.

(Woodward, Treatise on Heraldry 1-2)

English and French heralds watched together while their armies engaged on Saint Crispin’s Day in 1415, and at the end determined that the English were the victors. On reporting to Henry V, the heralds told him the name of the nearest fortified town, Azincourt, after which the battle was named. The principal French herald Montjoie appears as the character, Montjoy, in Shakespeare’s play, where we see him transmit communications between Henry and the French King Charles VI. In this respect, the herald is an historical forerunner of the modern international diplomat.

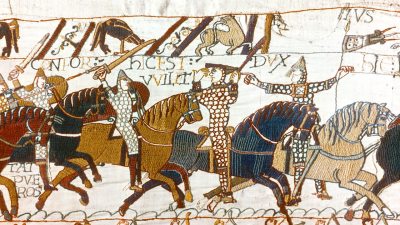

A momentous incident occurred for heraldry during the battle of Hastings in 1066. After William, Duke of Normandy (the Conqueror), sustained a fall from his horse, a rumour spread that he had been killed. To raise his troops’ moral, he lifted his helmet to show his face, as is famously recorded in a scene from the Bayeux Tapestry. That’s William, second from the right:

At this time combatants did not widely identify themselves by designs on their shields and armour, although various adornments do appear. One scene, for example, shows William’s standard, and the shields of many of the French warriors are decorated with a wyvern, or winged dragon, an emblem of the French army. (See Davenport’s discussion of the beginnings of armory in the tapesty in British Heraldry [1921].)

After the famous incident pictured, fighters across Europe took to painting individual emblems and insignias on their shields. This practice of ‘armory‘ developed sets of rules and conventions for elaborating the identity of fighters from the higher echelon, knights in particular.

The herald’s role expanded to regulate an evolving symbolic language and record the heraldic insignia of other personages of note, incorporating a multitude of details of family, accomplishment and entitlement. As coats of arms proliferated over time, disputes arose about who had the right to use a particular emblem (or charge) on their shield (escutcheon).

In 1389 Richard III himself decided the first heraldic legal case, which was fought over who had the right to bear the arms Azure, a bend or, subsequently known as the Scrope arms.

Perhaps in consideration of the simplicity of this form, and in anticipation of complexities to come, 1483 Richard instituted a Herald’s College or College of Arms to grant and control the use of arms in England (Grant, Manual of Heraldry p.6).

Various categories of arms came to include:

- Arms of Sovereignty or Dominion, those of the sovereigns of the territories they govern, such as the Russian Eagle and English Lions

- Arms of Pretension, those co-opted by a prince or lord with a claim to a certain kingdom or territory, such as through marriage

- Arms of Concession, granted in reward for virtue, valour, or extraordinary service

- Arms of Community, for bishops, cities, universities, academies, societies, and corporate bodies

- Arms of Patronage, for governors of provinces, lords of manors and the like

- Arms of Alliance, gained by marriage

- Arms of Succession, inherited or assumed by bequest, donation, etcetera

- Arms of Affection, assumed from gratitude to a benefactor

(Grant, Manual p.15-16)

So far in J.F. Smith’s Mystery of the Marsh, Lord Bury has actually looked for the Whiston name in the “Herald’s Books,” and would render William, not merely an outcast from their society, but a virtual nonentity. He damns the young scholar with faint praise for “plucky perseverance” at study, at the service of “his fixed determination to win a name” (Chapter 20). Smith clearly sides with Clara Meredith’s critique of Bury’s patriarchal attitudes:

‘Oh you men […] with your pride of rank, your worship of a mere accident, your absurd veneration for musty parchments and the Herald’s blazon […] you bow down before idols which have not even artistic beauty to recommend them.’

Lady Montague’s satirical observation, herself an object of partially affectionate satire for her snobbery, reflects an absurdly primitive susceptibility to totemic influence. (Durkheim notes the “analogies” of totems with the heraldic coat-of-arms.)

‘Are you not aware, Miss Meredith,’ she demanded solemnly, ‘that the crest of the Kepples is an eagle?’

‘Perfectly, aunt, I have seen it on her carriage a hundred times.’

‘And that the crest of this young man, if he has such a thing, is probably a goose, a sparrow, or some such ignoble bird, possibly a sucking pig,’ she added, in a tone of lofty indignation, which was completely thrown away upon her hearer, who could not repress a smile.(Chapter 22)

She alludes not only to an implicit hierarchy of creatures that portray totemically the characteristics of the families they represent, but also to what she considers the unnatural aberration that results from breeding across limits of class and status: “It cannot be. It shall not be,” she insists. “Nature and heraldry are alike opposed to it.” It is simply not done to cross eagles with geese or sucking-pigs; the devil’s work, we might say.

We can, in fact, find heraldic precedents, such as the anomalous creatures found in the coat of arms of the city of Great Yarmouth. After the Battle of Sluys against the French navy in 1340, as a gesture of thanks to the city for its contribution of men and merchant ships, King Edward III granted arms-of-affection, in the form of the three golden British lions passant (or “striding towards the [viewer’s] left”).

These were dimidiated with Yarmouth’s own three silver herrings, resulting in the curiosities. “Dimidiation” is the practice of combining two separate coats by dividing both of them vertically, then joining the sinister and dexter halves (meaning respectively those on the bearer’s left and right).

Great Yarmouth is only 18 miles from Norwich, the city of the author’s youth, so there is every chance that Lady Montague’s sarcastic comment quietly references the Yarmouth lion-herrings.

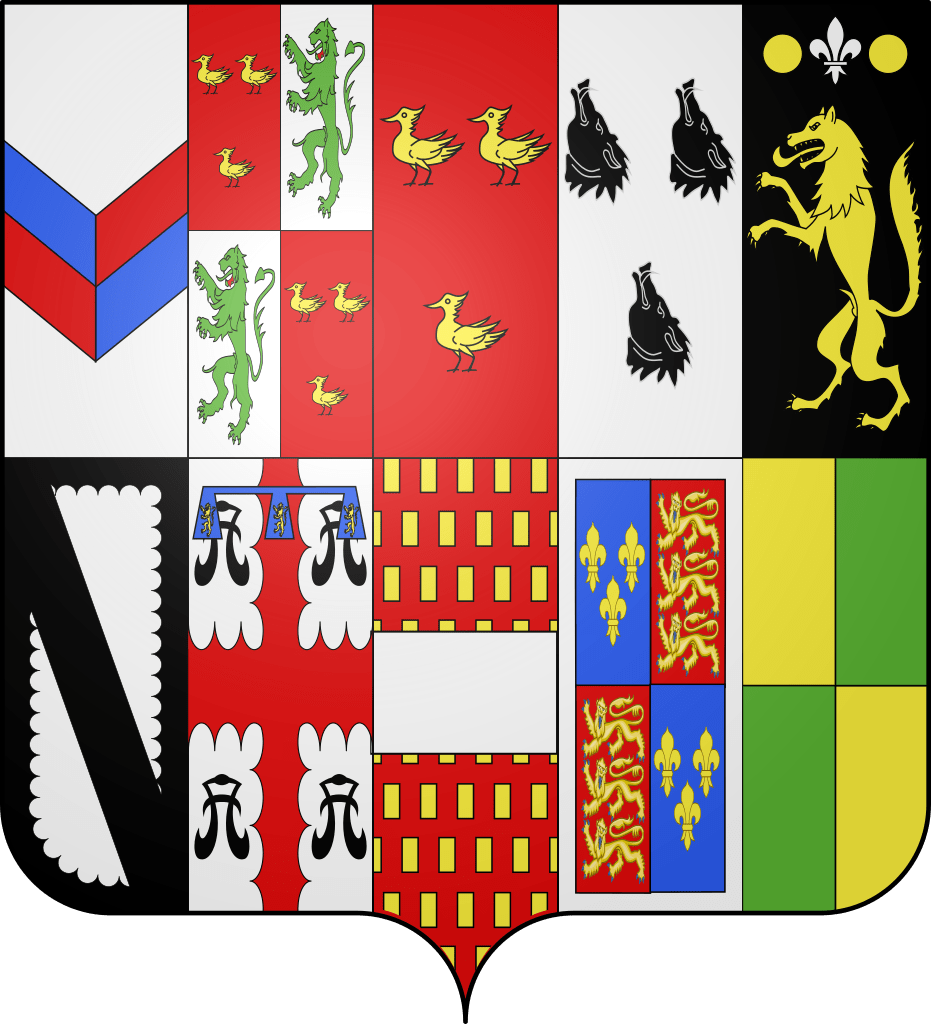

“Quartering” is a more evolved and versatile method of dividing coats of arms, such as occurs when families intermarry and inherit and otherwise acquire further arms. In principle, the term refers to dividing the shield into four parts by dividing it horizontally and vertically. In practice, it can extend by division into any number of rows and columns, in encompassing the complete arms to which an entity has a right. In order to show one’s maternal arms, for example, they may be quartered with paternal ones.

Here are the quartered arms of Pamela Vivien Kirkham, 16th Baroness Berners (b.1929). They are in a “quarterly of ten,” incorporating her entitled arms of Williams, Tyrwhitt and Jones, Tyrwhitt, Booth, Wilson, Knyvett, Bourchier, Lovayne, Thomas of Woodstock, and Berners:

In this sense, Smith’s narrator speaks this week of Lady Montague “[falling] back upon her quarterings,” which he considers to be “rather a feeble stay.” Lawyer Whiston’s reference to the Allworths’ “ancient,” “moth-eaten” title with its “unexceptional” blazon bolsters this skeptical view of heraldry and the peerage in general. Sir George Meredith’s comment in Chapter 22 expresses a similar attitude:

‘We are not in the peerage, Clara,’ he added, ‘but we might have been. Refused it twice. The Merediths can count quarterings with the Montagues and the Allworths.’

Chapter Twenty-three

Death of Farmer Hearst — His Will — Goliah’s Prospects Brighten

If Peggy Hurst did not bring her husband a fortune, she was not altogether dowerless. A sharp tongue and a strong will accompanied the gift of her hand, which, to do her justice, was a hard-working one. To such a woman it was no very difficult task to discover Peter’s weak points. Like setters, wives have a natural instinct that way. She speedily found them all out, and determined to govern him through them; an easy thing to accomplish — for the farmer had few brains, and was not much troubled with feeling — especially gratitude — else he had never lent himself to Peggy’s project of disgracing William, whose father had acted most kindly to him.

That it failed was no merit of his.

Parents must have had singular ideas of the discipline proper for children in those days, and it was no wise remarkable that Peggy shared the mistake, but commenced switching and spanking both her daughter and our hero at a very tender age.

The boy was the first to rebel. On the last occasion his aunt ever made to punish him he snatched the switch from her hand, kicked the shin of the hired man, who had been ordered to hold him, and declared, passionately, that he would run away to his uncle in London. This settled the question as far as William was concerned; for Peggy stood in some awe of the lawyer, who, on his annual visits to look over the accounts, spoke so little, paid her no compliments, and exacted the last shilling due to his ward.

The whippings of poor little Susan, however, were still continued, to the great distress of Willie and secret annoyance of her father, to whom she sometimes ran for protection, which the weak headed cipher had not courage to afford.

At last the farmer did venture to interpose, not openly — that was not to be expected — but in his usual timid, hesitating, sly way, by asking his wife if she did not think it time Susan should attend school.

Peggy regarded him fixedly, and asked what put that crotchet into his head.

‘Nothing— that is, nothing particular, my love. Only William’s uncle will be down in a month.’

‘I do hate that man!’

‘The boy says he shall ask him to remove him from the farm; that he won’t stay here to see his cousin whipped daily. You, of course, know best, my love,’ he added.

This last observation somewhat mollified his wife, who merely muttered, in allusion to her nephew:

‘The little wretch!’

‘I sometimes think,’ continued her husband, ‘that the lawyer is rather fond of Willie. He does not show it much, but that is his way, I suppose. We shall miss the money for his board,’ he added.

The last shot told, for it was levelled where Peggy was most sensitive, her interest, her tenderest feelings being in her pocket. She made no observation at the time, but from that day the whippings erased, and the nephew so far forgot his resentment in pleasure at the change that, when his uncle arrived, they were not even alluded to.

Goliah and Lawyer Whiston were driving along the beaten highway to Deerhurst.

‘Is Peter really so ill?’ inquired the latter.

‘Mortal bad; three doctors ha’ been at him.’

‘Did Mrs. Hurst send for me?’

‘Not she. It war Susan told I to come. Thee be about the last person Peggy wants to see at the farm.’

His companion regarded the speaker with a smile, rather surprised, perhaps, at his intelligence.

‘And so we thought it best —’

‘We!’ interrupted the gentleman. ‘How long have you been a plural?’

‘What be that? I an’t been a plural as I knows on.’

‘Nothing. Thinking of something else,’ said his companion. ‘How long have you and Susan been such excellent friends?

Goliah regarded him with a half doubtful, half comical expression, as if he wished to trust him, but did not feel quite convinced of the prudence of doing so. Probably he regarded the step he meditated as a sort of forlorn hope, but after a moment’s deliberation, bravely took it.

‘Susan and I be in love,’ he said.

‘Ah! ah!’ ejaculated Mr. Whiston. ‘A suitable match.’

‘Does thee really think so!’ exclaimed the rustic.

‘Of course I do, really and truly.’

‘Then thee beest an honest man,’ added the lover.

‘Thank you; but you must not flatter me,’ observed the gentleman.

‘I won’t. I allays told Willie,’ added Goliah, ‘that thee wor an honest man for a lawyer.’

The recipient of this rather equivocal compliment gave one of his quiet smiles.

‘The farmer be willin’,’ continued the speaker, ‘but his wife won’t hear on it — dead agin it. She wants her daughter to marry Benoni Blackmore, the schoolmaster’s son. They often meet i’ the Red Barn to talk matters over. They both do hate I,’ he added.

His hearer recollected what the honest rustic had told him of the medicine his rival brought from the Bitterns’ Marsh for the farmer.

‘Surely,’ he observed, gravely, ‘you do not suspect any foul play?’

‘Lord bless thee!’ he said, ‘no. Nothin’ o’ that kind. Peggy be bad enough, but not bad enough for that. She wouldn’t hurt a hair of her husband’s head. She might pull out a few,’ he added, with a grin. ‘But p’ison! She wouldn’t p’ison even me. It was only herb drink, which some old woman at the marsh makes up. Folks say she be mortal clever.’

Still the lawyer regarded him doubtfully.

‘I tell ’ee no,’ continued the speaker, earnestly. ‘Susan wouldn’t let her father take it. Maybe she had some such thought. Not agin her mother, but Benoni. But I know it wor all right. He hadn’t the pluck. So I swallowed a bottle of the stuff to satisfy her, and mortal nasty it wor.’

This assurance, and the details confirming it, afforded his hearer great relief. It would have been a most distressing circumstance for William’s aunt to have been arraigned for. murder.

‘We are getting near to Deerhurst,’ he observed. ‘Now, Goliah, attend to my directions.’

‘Yes, I will.’

‘Pay no attention to anything I may say to Mrs. Hurst. I am going there in your interest and Susan’s; not hers. Possibly I may seemingly take sides with her, merely to–‘

The lawyer hesitated. Possibly he did not like to complete the sentence.

‘I sees,’ exclaimed his companion, finishing it for him. ‘Pull the wool over her eyes. It will be a cunning trick that, and rare fun to see it; but thee canst do it — I know thee canst. Thee beest a lawyer.’ Evidently the speaker had not overcome all his prejudices against the profession, but he discriminated — made exceptions — that was something towards it. ‘

By this time they had entered the village.

When Peggy Hurst saw the only man, perhaps, she had ever stood in dread of, accompanied by the one she most hated, drive up to the door of farm, she coloured with vexation and anger.

‘Walk in, Mr. Whiston,’ she said. ‘Of course I am glad to see you. Not that I think poor, dear Peter is as sick as the doctors say. But as for that impudent, prying, meddlesome, mischief-making fellow,’ she added, pointing to Goliah, ‘he sha’nt set a foot in my house. He is not one of the family. He is not William’s guardian, and I can’t allow it .’

‘I have not the slightest intention of asking him,’ observed the visitor, coolly. ‘ In fact. I see no necessity for doing so; had there been, I should not have asked your permission. Half the house is my nephew’s. Let me advise you to keep a civil tongue in your head — a very civil one — for should your husband die the arrangement which gives you a home here will expire with him.’

This was gall and wormwood with a drop of honey mixed with them, the honey being the tone of indifference in which the speaker alluded to her daughter’s suitor, who grinned with delight at hearing her thus lectured.

‘I don’t want to come into yer house, Mrs. Hurst,’ Goliah cried. ‘My own house is quite good enough for I, and it is our own — all on it, not half. The squire has paid I for bringing him down,’ he added, ‘and I ha’ naught more to say.’

With this parting shot, which Peggy felt too indignant to answer, he drove off, whistling a tune as he went.

When Mr. Whiston entered the sick man’s chamber he perceived at a glance the wisdom of the precaution Susan and her lover had taken in sending for him. The farmer was greatly changed, and evidently had not many days to live. Such at least was his impression, which the two medical gentlemen whom he found in the room, soon confirmed by a few whispered words. Susan, who was seated by the bedside — she had been his constant nurse — appeared to be crying bitterly. Despite his weakness, and even worse failings, she loved the old man dearly. He was her father, had been kind to her, as far as he dared; added to which she felt that it was not for the child, at such a moment, to judge its parent.

‘You need not whisper,’ said Peter Hurst, in the querulous tone peculiar to sickness. ‘I know what you are saying as well as if I had heard the words. How long, Mr. Whiston,’ he added, after a pause, ‘did the doctors tell you that I had to live?’

‘That is a question they cannot always answer,’ observed the lawyer, kindly.

‘Well,’ continued the patient, half muttering to himself and half aloud, ‘it can’t much signify. I am glad you are come, for my poor girl’s sake; she was always kind and good to William, so you will protect her on his account.’

‘On her own,’ said the man of law, firmly; ‘but to do so effectually I must possess full authority.’

‘You have it,’ answered the farmer, in an undertone, ‘The last time I went to Colchester to sell the hay I made my will — that is, Squire Smithers made it. You are sole executor. Be kind to Susan; she has been a good, affectionate child to her poor old father.’

‘Susan,’ he continued, after pausing to recover breath, ‘open the case of the cuckoo clock.’ He pointed to a large, old-fashioned piece of furniture standing in one corner of the room — it had been his grandfather’s, but long since valueless as a time-keeper. His wife never went to it, and had frequently requested him to exchange it for a modern one, but had failed to persuade him to do so.

‘There are two packets, father,’ observed his daughter, who had complied with the directions.

‘Bring them both,’ said Peter — ‘I had almost forgotten the other — and give them both to Uncle Whiston; but, first, let me see them. This is my will.’

The lawyer placed it in the inside pocket of his vest.

‘And this,’ continued the dying man, who was evidently exhausted by the exertion he had made — ‘I can scarcely tell you what it is. I found it behind one of the beams in the chamber of the Red Barn, three years ago; but you will be able to make something of it.’

Our readers will not have forgotten the parcel which Bunce saw the eldest of the fugitives conceal in the little room on the night they so nearly fell into the hands of the two tramps. Believing it contained letters or papers important to the interests of the Lady Kate, Martha had abstracted them from the desk of the French governess, Mademoiselle Joulair, and taken them with her on their flight.

A smile of satisfaction rested on the countenance of Mr. Whiston, to whom a cursory glance had revealed their value, and he placed them, even more carefully than he had done the will, in the same secure pocket.

One of the medical men now recommended his patient to take a little home-made wine with bark in it. His daughter administered it. It seemed less bitter from her hand.

‘He cannot last long,’ whispered the second doctor to the lawyer.

‘Not a word of what has taken place,’ observed the latter; ‘it might only disturb the last moments of your patient, and provoke unseemly discussion.’

The gentlemen understood him — they were well acquainted with Mrs. Hurst — and bowed assent.

The caution was not given one whit too soon, for the next instant Peggy came bouncing into the room. In her impatience to see Goliah safely off the farm she had forgotten her interests till the idea struck her that something prejudicial to them might be taking place. Looking suspiciously round, and seeing neither paper, pens nor ink were upon the table, her excitement cooled down. She noticed that the lawyer was watching her, and recollected the part she would be expected to play, that of an afflicted wife.

‘Poor, dear lamb!’ she said, shedding a few natural tears. Perhaps her conscience did reproach her. ‘Oh! doctors, can you do nothing for him?’

The medical men shook their heads, and the speaker sank down upon her knees by the side of the bed as if in prayer. We trust it was sincere.

‘You have the will?’ murmured the dying man. ‘Keep it safe.’

Whether the question had been intended for Mr. Whiston or his wife, we cannot decide. Peggy took it to herself.

‘Yes, Peter dear,’ answered the almost widow. Our separation will not be very long. We shall soon meet again, never to part.’

The prospect thus held out did not seem to afford much satisfaction; in fact, it rather appeared to scare him. With a last effort he turned from her to the side of the bed where Susan, sobbing with grief, was sitting, gazed upon her fondly, then closed his eyes for ever.

He had at least one consolation in dying — the last gaze that met his was that of true affection.

That same evening Mr. Whiston returned to London, promising to come down again in time for the funeral.

When he arrived the widow received him much more cordially than on the previous occasion. Then she had her doubts; there were possibilities to be guarded against; now everything seemed clear and satisfactory. Had she not the will, made years since under her own direction and approval? Peter’s worldly possessions would soon be in her hands, her daughter dependent upon her, her rule unshakable! Mr. Whiston came in his own carriage, too; that gratified her pride. Neighbors would see that she was well connected.

We need not describe the funeral ceremony; the tears, artificial and genuine, shed on the occasion. There was at least one sincere mourner — the dead man’s child.

On the return to the farm Peggy carried her confidence so far as to consult the gentleman on the steps necessary to prove her late husband’s will.

‘Probate must be taken at once,’ he replied. ‘We can do nothing till that is done. Let me see. Deerhurst, county of Essex, diocese of London. Doctors’ Commons will be the place. You must come up to town.’

The widow hinted something about the expense. She could not think of going there alone, leaving Susan behind, and giving that wretch Goliah a chance of seeing her.

‘Pooh! Pooh!’ said Mr. Whiston. ‘Take no trouble about him, or the expense either. I shall be happy to receive yourself and daughter at my house in Soho Square.’

The invitation was accepted as much from pride as economy, and the widow came to the conclusion that, after all, the lawyer was really an excellent person — a little odd, perhaps — but, then, he was an old bachelor — sufficient explanation, in most female minds, to account for any amount of eccentricity, short of insanity. As Goliah suggested, he had pulled the wool over her eyes completely.

Like most of his profession, Mr. Whiston was a far-seeing man — made his arrangements beforehand; he detested nothing so much as being taken by surprise. With this end in view, he waited upon Lady Montague; the first time he had seen her since what his aristocratic client termed her niece’s preposterous engagement.

Time had cooled down her anger, without removing her ladyship’s objections; but the sight of William’s uncle revived the former in all its original force. ‘So, sir,’ she exclaimed, ‘you have called at last. This is a pretty affair — my ward, Lady Kate Kepple, engaged to your nephew! Preposterous. It is no use your arguing. If Lord Bury has been silenced, I have not. Can’t understand him. But one thing is certain; I will never give my consent.’

Many women, when aware of their weakness, have a habit of reiterating their determination to others, in order to keep up their courage.

‘I can only say,’ observed the gentleman, calmly, ‘that I felt as much surprised as your ladyship appears to be, when my young relative informed me of it.’

‘No doubt you did!’ said the aunt, sarcastically, ‘and delighted.’

‘Oh dear no, Lady Montague,’ answered the lawyer. ‘It was all very well; but I saw nothing in it to delight me. On the contrary, a considerable amount of vexation and trouble.’ The lady almost gasped with astonishment.

‘William’s fortune,’ continued the speaker, ‘will, in all probability, be a large one. His talents are acknowledged to be of an exceptionally high order. He is of the material of which lord chancellors, statesmen, and prime ministers are made; but youth is naturally impatient. Had he been content to wait, possibly he might have done better.’

This time Lady Montague actually did gasp. This coolness and self-possession, where she expected to meet only confusion and respectful entreaties, actually dumbfounded her.

‘Better!’ she gasped; ‘better!’

‘Pray do not misconceive me. In person, fortune, and family, your niece is unexceptionable.’

‘I should think so, Mr. Whiston.’

‘There are other advantages, important only in a worldly sense, I grant you — such as political connections,’ observed the lawyer — ‘things to be considered.’

His hearer drew herself up with a stately air.

‘You forget yourself, sir,’ she observed severely; ‘Lady Kate Kepple is the granddaughter of a duke!’

‘An estimable person in his time, no doubt,’ remarked the gentleman, ‘but weak, unfortunately very weak. The conduct of his duchess drove him to suicide instead of the divorce court, where a more sensible man would have gone. She is also the niece of Viscount Allworth,’ he continued, in a slightly sarcastic tone, ‘a very ancient title, blazon unexceptionable — so ancient that it has become somewhat moth-eaten.’

‘And mine?’ said her ladyship, drawing herself up with a stately air. She felt that she was getting the worst of the argument, and fell back upon her quarterings. As the world goes, rather a feeble stay.

‘And that is her noblest boast,’ replied Mr. Whiston, bowing with formal courtesy. ‘The reputation of Lady Montague is as unspotted as her heart. The slander-loving gossips of society, the human flies that live on carrion, have never yet discovered a taint in it.’

The compliment, no less merited than graceful, was skilfully paid; few women could have resisted it.

‘Ah, well! You have such an odd way of putting things,’ observed the recipient of it, her excitement calming down considerably. ‘If you could only persuade your nephew to be reasonable.’

‘He is reasonable, very reasonable, for his age,’ said the lawyer; ‘it is hardly just to judge the impulsive feelings of youth from the standpoint of age. Pardon the allusion. Are you not alarming yourself unnecessarily? A hundred things may occur to change the feelings of Lady Kate and my nephew, while harshness and unwise opposition might tend to confirm them. My own experience in life,’ added the speaker, ‘tells me that comparatively few persons marry the object of their first attachment.’

‘O, I am not angry with Kate,’ exclaimed the aunt.

‘I presume not,’ was the reply. Lord Bury was not present, and if he had been, his nice sense of honor would have held him tongue-bound. Possibly, also, the recollection of certain innocent flirtations in her own juveniles days, which had ended in nothing, occurred to her ladyship.

‘Perhaps we had better change the subject; but let it be understood that my consent will never be given to their insane project.’

Her hearer smiled. Probably he knew the value of such resolutions. Lady Montague’s heart was, after all, much better than her head.

‘And now, Whiston,’ she resumed, ‘that this question be settled — quite settled, mind that — allow me to ask the motive of your visit? It cannot have been to say all these pleasant things to me ?’ she added good-humouredly.

‘Certainly not,’ was the reply. ‘It was intended, in the first place, for Lady Kate Kepple, whose sympathies I wish to enlist in behalf of a good, fatherless girl I am left guardian to; her mother, a most unwise person, is not fitted to be trusted with the office. She wishes to force her into a highly improper marriage.’

‘Have you accepted office as Cupid’s attorney-general?’ demanded his hearer, laughingly. ‘If so, I fear the more lucrative part of your practice will suffer. But what can my niece do?’

‘Everything,’ answered the lawyer; ‘by receiving her as a humble companion; in time, I trust, as a friend. She is of respectable birth; been reared in the country, unblemished in character — that I pledge my own reputation to — and requires no salary. Before speaking with Lady Kate upon the subject, I felt that it was only respectful and fitting to obtain your sanction.’

‘Very proper,’ replied Lady Montague; ‘most unexceptionable proceeding. Of course, I have no objection. Ah, Mr. Whiston, if you were only as reasonable and considerate in other things! But we will not touch on that subject again.’

What followed were mere matters of detail unnecessary to enter into, it being understood that the protegee of the lawyer would be received at any time he thought fit to bring her. Somehow the gentleman forgot to inform his client of the name of his ward. We will be a little more frank, and hint to our readers that it was Susan Hurst. We suspect they have already guessed it.

This edition © 2020 Furin Chime, Michael Guest

References and Further Reading

- Davenport, C. (1921?). British Heraldry. Jump to file on Internet Archive

- Durkheim, Emile (1915). The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, 113. Jump to file at Gutenberg.org

- *Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. Jump to file at Gutenberg.org

- Grant, F.J., ed. (1914) Manual of Heraldry. Jump to file on Internet Archive

- Woodward, J. (1896). A treatise on heraldry, British and foreign: with English and French glossaries. Jump to file on Internet Archive

See also

- Droulers, Olivier (2016). “Heraldry and Brand Logotypes: 800 years of Color Combinations,” Journal of Historical Research in Marketing 8.4 (507). Full text available free at Researchgate.net

- Moncreiffe, I. and Pottinger, D. (1979). Simple Heraldry: Cheerfully Illustrated (NY: Mayflower)

- The Heraldry Society (Quartering)

- Heraldica (Canting Arms)

- Heraldry of the World

- International Heraldry and Heralds

- Eastern Daily Press. “How did Yarmouth get its half-lion half-fish coat of arms?” (June 2015)