Harry has returned to Paris, and in this chapter he has to deal with the dangerously paranoid delusional antics of his brother, and the effect of his behaviour on everyone around him. The use of the word ‘lunatic’ in a medical sense serves to remind the reader that through the pages of the novel we are also exploring a world of over a hundred and thirty years ago. The term is derived from the Latin term ‘lunaticus’ which referred to those Romans suffering epilepsy or another demonstrable form of mental illness and attributed their behaviour to the effects of the moon.

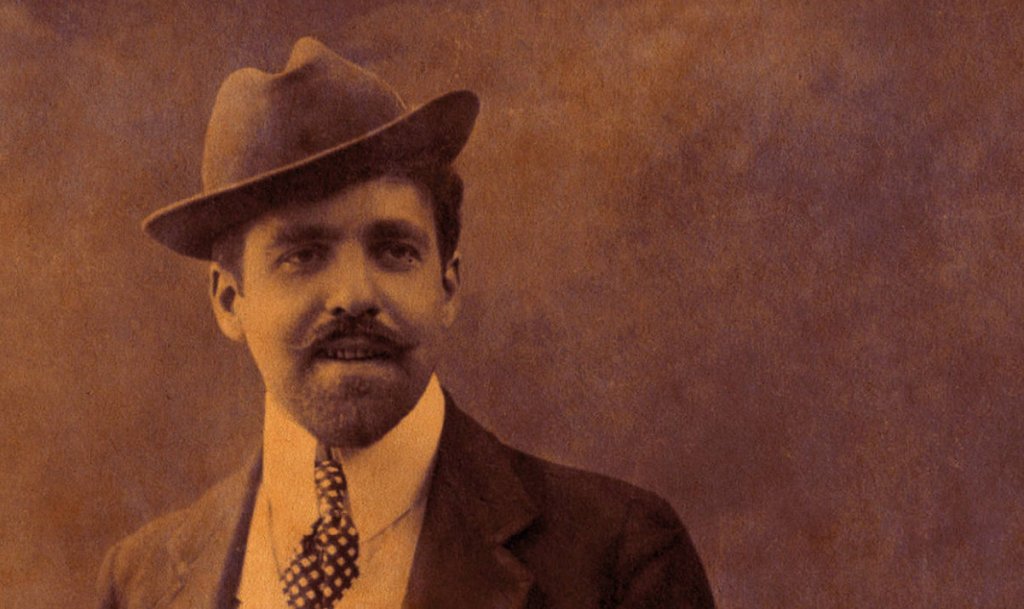

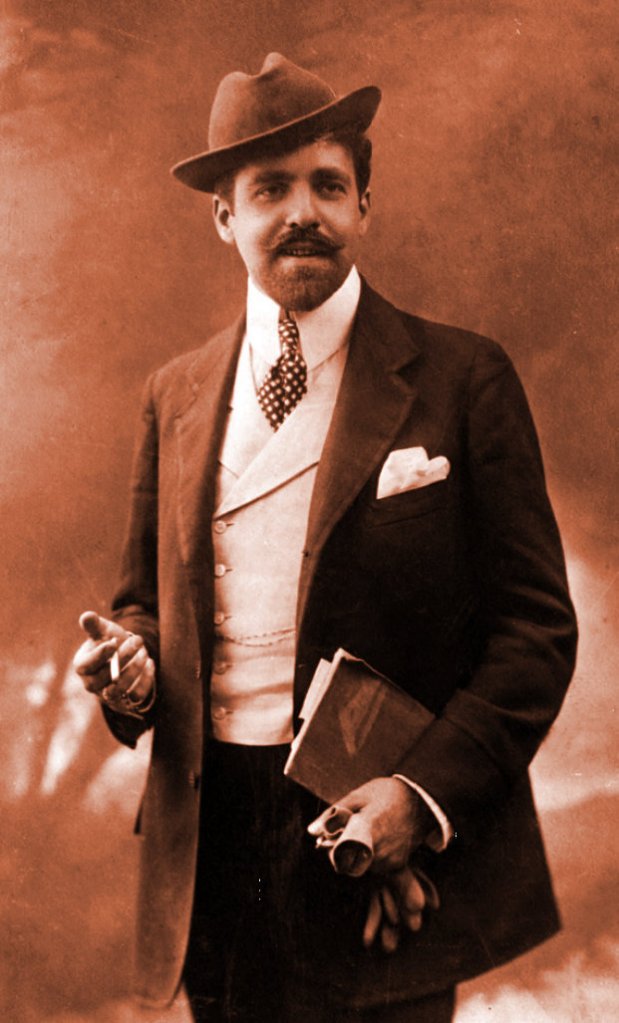

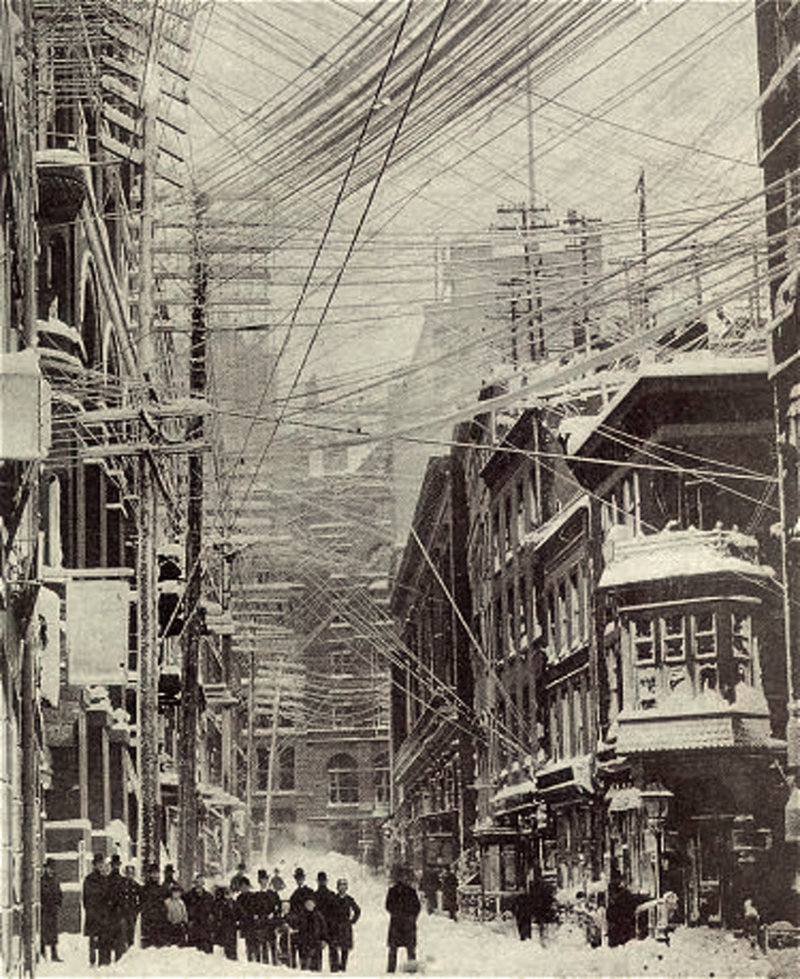

Harry calls in a well-regarded French doctor to examine Frank/Francois, his brother. The Doctor from his wealth of knowledge offers two alternatives as causes: nerves or the brain. He goes away saying he will think on it, for it is patently obvious he hasn’t got a clue. Lay people of today, without medical degrees, might have a number of suggestions for Frank’s behaviour, in contrast to people of the time, who were lost for explanation. Sigmund Freud had only just begun his work developing psychoanalysis, which in due course, besides treating those with a mental illness, will endow us with another way of looking at ourselves and our lives. Those of the late 19th Century are on the cusp of great changes in human life and perception. Between ourselves and readers of the time, there is a huge gulf; most have yet even to experience instant electric lighting, which will brighten and expand a person’s day considerably.

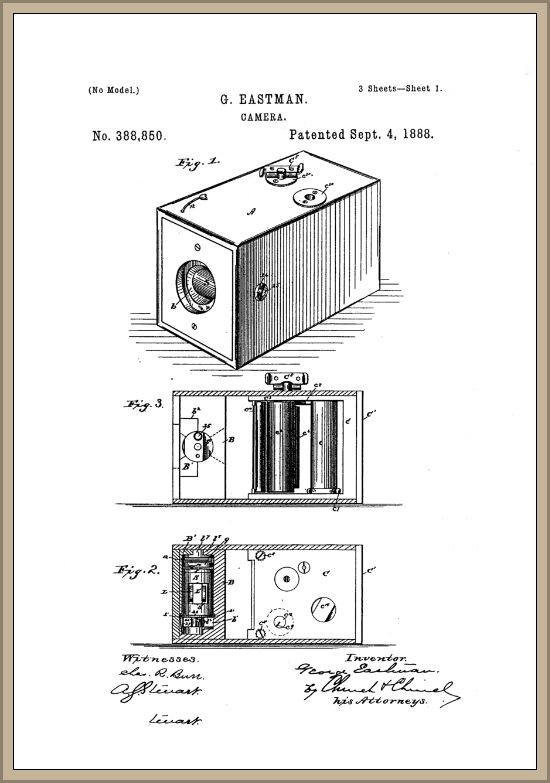

‘Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,’ is a well-known quote from writer Arthur C. Clarke. A recent invention of the time which also heralds a change in human perspective comes into Frank’s hands. Invented by George Eastman, the first Kodak camera went on sale for $25 in 1888 with the advertising line: ‘You push the button, we do the rest.’ The camera, which lacked a viewfinder, came with a roll of film capable of producing one hundred oval-shaped photographs. Once completely expended, for the sum of $10 a customer could return the camera to the Eastman Dry Plate Company. The worthwhile photographs were returned, together with a fully loaded camera ready to go again (Smith). This, in 1893, may be the first instance of a roll-film camera to be used in a fictional novel.

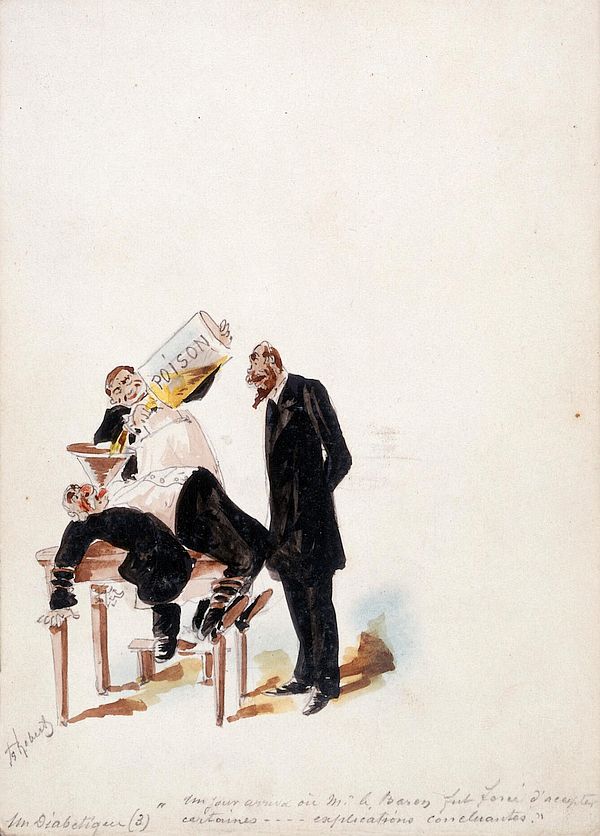

Frank admits to Harry that he has bribed members of the French Chamber of Deputies (the legislative assembly) to support the Lottery Bill for Baron Montez. History supports the fact that this practice was widespread throughout the company’s dealings. In the investigation that followed the collapse of Compagnie Universelle, one Deputy, Jules Delahaye alleged that one hundred and fifty members of the government had accepted bribes. In the anti-Semitic newspaper La Libre Parole, Baron Jacques de Reinach, the company’s Chief Financial Adviser was accused of bribing twenty-six Deputies (Parker, p. 187-188). The question arises though as to why Montez, who has divested his interests in the canal project, should wish to bribe Deputies to assist in the passage of the Bill? Perhaps Montez is working on behalf of another third party? It remains an outstanding mystery.

For today’s reader, this novel carries out a function and enchants us in ways Gunter never intended. Through the novel, as in examining old photographs, we catch a glimpse of life in the latter half of the 19th Century; but that is not all, because the novel is itself an artefact of the time. Artefacts generate a number of dimensions—the selective world of the novel as portrayed by Gunter, where life depicted is conditional on the needs of the story. In the characters’ world, there is no squalor in the streets, no visibly homeless or wretched, no crush of immigrants in New York, no description of the pitiful conditions and state of workers on the Panama Canal, in the streets no dead of Yellow Fever, and in Paris, no detail of the machinations of the French government concerning the canal.

Then there is the writer’s intent of Gunter himself, the choices of content, and the decisions made, all flavoured by his personal character, knowledge and opinions—all designed to entertain a perceived readership. Lastly, we in the 21st Century, judging by the success of the its publication, have the opportunity to gain an impression of the 19th Century audience. The novel offered readers an escape from the mundane and their toilsome lives, which are not without the common realities of the time. They seek adventure, travel, exotica, true love, a retinue of servants at their beck and call, a life untroubled by irksome necessities like work, sanitary disposal, drawing water, lighting fires and cooking for oneself and others. In their escapism, they may be very similar to readers today.

As the chapter closes there is a surprise visitor awaiting Harry at the front door. Guess who?

BOOK 5

THE HURLY BURLY IN PARIS

CHAPTER 22

THE MIND OF A LUNATIC

The door is closed behind him. Harry says to the old man: “Robert, just get my baggage upstairs; and where is my brother?”

“Trunks, yes, sir,” replies Robert. Then he turns to Mr. Larchmont, and astonishes him. For he says: “Thank God, you have come, sir! It was on my mind to speak to a lawyer tomorrow!”

“What’s the matter?” asks Harry. “Anything wrong?” for Robert’s manner is alarming.

“Yes, sir! Mr. Frank, your brother—he’s sick. I think it’s his head.” The man waves his hand about his honest Breton brow, as if driving away phantoms. “But you had better go in and see him yourself, sir, at once.”

“Very well,” says Harry. “Is he at dinner?”

“Oh! he don’t dine much, sir and Miss Jessie and her governess generally eat upstairs, sir.”

“Where is he?”

“In the library.”

And Robert shows Harry Larchmont into a dimly lighted room, where a man is seated before a writing table, his head in his hands.

Harry cries out: “Frank, I’ve come back from Panama safe! The fever didn’t kill me!”

“Ah, thank God! Harry! You are come!” answers the brother, rising, and the two wring each other’s hands; though Francois after the manner of the French would kiss.

“Let me have a little light to look at you,” says the younger one, for the tones of Franc̗ois Leroy Larchmont’s voice have given him a peculiar thrill, they are so nervous yet so muffled; the timbre of the voice seems to be changed. It is as if his tongue were clumsy.

Lighting the room, Harry Larchmont looks at his brother, and can hardly restrain an exclamation, the shock of his appearance is so great.

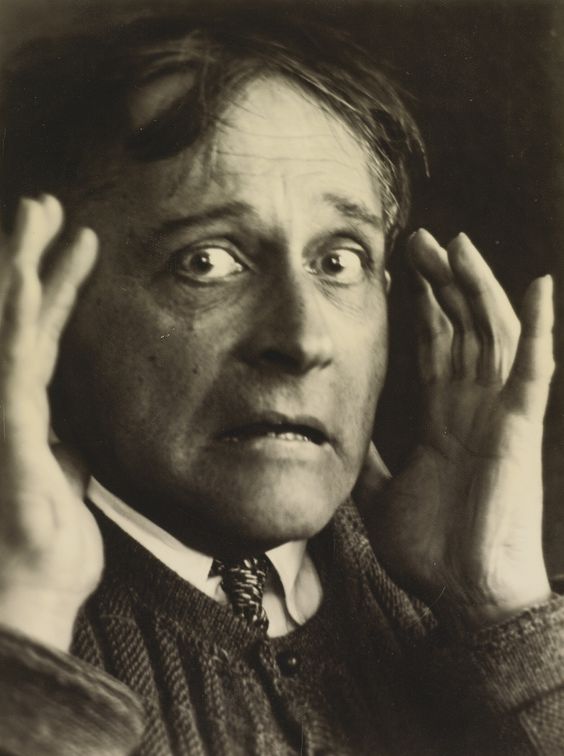

The face that had been round and rather full, has grown thin and drawn. The eyes have a watchful furtive glance, as if looking for something, partly in terror, partly in surprise—a something that is always coming but never comes.

Before the younger man can speak, the elder breaks out: “Thank God! You’ve come to save Jessie from marrying that infernal villain—that Montez of Panama and Paris!” Then, not waiting for an answer, he jumps on, the words coming from him in jerks: “I’ve had cables from him! Threatening cables!—from New York! cables that alarmed me so much! cables!—that I had all the preparations made for the wedding—the trousseau ordered here—knickknacks and folderols! He is coming tomorrow! But you—thank God!—in time! Henri, my brother! save me from him!” and he shudders as if frightened.

“Let me look at his cables,” remarks Harry grimly.

The other exhibits to him rapidly, three—one from Panama, two from New York. The general tenor of these is for Franc̗ois to make all the preparations for the wedding, that must take place on Montez’ arrival in Paris, though there is a peculiar ambiguous threatening in them.

“What does he mean by his hints?” asks Harry, and is astounded at the reply.

His brother suddenly giggles: “Ah, ha! I bribed the deputies for him! The deputies for the Canal Bill! The Lottery Bill! It went through the Bureau of Deputies, a few nights ago! I bribed them! He hints, he absolutely dares to hint, at threatening me with this, the wretch! for doing his work—oh ho! his orders!” Then he shudders: “Henri, protect me!”

“Certainly!” mutters the younger man, almost too overcome to speak, for there is something in his brother’s manner that makes him fear for his intellect, though he meditates: “Why could I not threaten Montez also? If it is against the law for my brother, it is against the law for him!”

But as Harry looks on Franc̗ois Leroy Larchmont, who has suddenly begun to tell him of a new opera, he casts this from his mind, speculating: “What jury would believe his evidence?”

Franc̗ois is never quiet long. He breaks in suddenly:

“But about this marriage. I have had a plan—a great plan. Within the last three days I have discovered how to postpone the wedding! What do you think I have done? I have made Jessie younger!”

“Made Jessie younger?”

“Yes! she is now only eleven!”

To this Harry returns, his voice very serious: “Where is she?”

“Oh, upstairs, studying her lessons, I presume. You’ll see her in a moment!” Francois rings the bell, and Robert making his appearance, he commands sternly:

“Bring the child down!”

At which, stifling a grin, the servant goes away; but a minute after, reappears with a subdued but frightened giggle, saying: “The child says she won’t come down!”

“Very well, I’ll see her myself!” answers Harry. “Never mind about coming with me, Frank! You stay here quietly,” for there is an indefinite fear in his mind—a fear of something, he does not know what, as he steps in the hall.

Noting his face, the servant whispers to him: “Miss Severn is all right! She’s upstairs with her governess, locked in. They’re frightened to death of him!”

So Harry, going up, raps on the door, and the faint voice of the governess comes faltering through the panels: “Miss Jessie is at her lessons—she can’t be disturbed, M-m-monsieur Franc̗ois.”

“Never mind whether she’s at her lessons, or not,” cries Harry. “It is I, Harry Larchmont! Open the door!”

In a second the key is turned in the lock, the bolt slipped, and he finds himself with both the governess and Miss Severn hugging him together, and sobbing: “Thank God, you have come! Thank God!”

But here he utters a cry of astonishment, and ejaculates: “What’s this? The ballet, or skirt dancers?”

And Miss Jessie cries: “Good heavens! don’t you know? I’m a child again!”

“Yes, and a very pretty child!” laughs Harry, for relief has come to him.

At which the young lady puts on a very blushing face, and says: “Now don’t be awful! No joking! I had to do it! Frank came up three days ago, and frightened me and my governess to death. He said I was a child once more! He had my governess make short dresses for me. He said that would prevent Montez from marrying me so soon! I would be too young!”

“How dared you do this?” asks Larchmont savagely of the governess.

The woman bursts out sobbing, and gasps, her nerves having given way: “Wouldn’t you do anything, if he had a pistol in his hands, and said it was the will of God?”

“But why didn’t you escape from here?” asks Harry, turning to Miss Jessie.

“How could I go out in these clothes? He took all the rest away! Look at me!” Then she suddenly cries, “No! For heaven’s sake don’t look!” for Harry is obeying her, and turning his eyes upon a babyish but alluring picture. Miss Severn is dressed as a Parisian child of eleven, with very short skirts, with very pink silk stockings and petite slippers, and baby waist with blue knots of ribbon upon her gleaming shoulders and round white arms, and golden hair hanging in one long juvenile pig tail.

“Then why didn’t your governess go?” mutters Larchmont, stifling a guffaw.

“She was too frightened to move, so we just locked ourselves in. Please—please don’t laugh at me! I—it’s awful!”

“And Mrs. Dewitt?”

“Mrs. Dewitt has been in Switzerland for a week. She will return soon.”

“We knew you were coming also,” continues Jessie. “We had seen your telegram. We thought it best to await your arrival. It would make such an awful scandal about poor Frank! But, oh,” here her eyes grow frightened, “don’t leave me with him!”

“How long has this thing been coming on the poor fellow downstairs?”

“Well, when we came back, Frank was all right, and I had a very pleasant time in society here, but each day, for the last two months, he’s been growing more nervous. I think it’s the threats of that awful man, the Baron Montez, made to him before he left for Panama. Then he has been very busy doing something political, he says; but only three days ago did this peculiar freak come upon him.”

“You saw Baron Montez when he left for Panama?”

“Oh, yes, once. He left Paris just as we got here. To please Frank I went down to see him. I—I had to—Frank is frightened to death of him.” Then she whispers “He is making preparations for my wedding. The trousseau is here. The time has been fixed by cable;” next giggles: “Would you like to see the bride’s dress?”

This is said so carelessly that Larchmont is astonished. He asks: “Did you not fear that Montez might really marry you?”

“No,” replies the girl, looking with trustful blue eyes into his, with such faith that it gives him a shock. “No, because you had sworn that I should never marry him!”

Then Larchmont says quietly to the governess: “I will make proper arrangements for Miss Severn so that she can come downstairs with—propriety.”

At which the girl gives a little affrighted “Oh!” and stands a beautiful and blushing picture.

From this the young man turns with a sad but stern face, and goes downstairs to see his brother, and coming into the library is greeted with: “Is the child still sulky?”

“No,” returns Harry, “the child is quiescent.”

“Ah!” remarks Franc̗ois, contemplatively. Then he suddenly giggles: “She was in a devil of a temper till I kodaked her!”

“You—did—what?” ejaculates Harry, for the term is a new one.

“Yes, snapped her in—photographed her—I’ve her picture here. I’m going to send one to Montez.” And Franc̗ois, who is an amateur at everything, produces a carte de visite of Miss Jessie that makes Harry Larchmont, serious as is the situation, guffaw.

“Would even Montez dare to marry such an awful child as that?” remarks Frank.

“No. I’m blowed if he would!” returns Harry: for he is looking at the most enfant terrible on record.

Miss Jessie’s blue eyes are starting out of her head in horror, but have tears in them; her mouth is pouting, but wildly savage; her pigtail is flying out in the breeze; she seems about to fly at the camera and destroy it; in fact, this had been her idea, but Frank had snapped too quickly and too deftly.

“Wouldn’t that make an artist’s fortune!” remarks Franc̗ois. “I shall ask her to pose for me—you know I daub a little—at least I did before that villain Montez made me walk the floor all night!” Then he moans, “Save me! He’ll put me in prison!”

Meeting Harry’s eyes, Franc̗ois Leroy Larchmont droops his, as his brother says: “There is only one thing to do, Frank! You, yourself, when you think of it, must conclude that I am the only one to protect you from Baron Montez!”

“Yes,” answers the other, “I have prayed for your coming!”

“Very well then, in order to save you from the man you fear, I must have the full direction of everything. You must assign your guardianship, under the French law, of Miss Severn, to me. She will assent to it in writing, and at her age, it will be legal.”

“You—you—” gasps the weak man, “will give me a receipt for Jessie’s property, so that they cannot prosecute me for losing it—a full receipt?”

“Yes,” says the other quietly, “a full receipt, to save your name!” And he breaks out: “Good heavens! You don’t suppose that I could ever let a child, your ward, lose her property through you! That would be a disgrace upon our family forever. But you must turn me over everything you have.”

“All right! Only save me from Montez!”

“Very well!” remarks Harry, “give me your keys!”

He steps into the hall and says to Robert: “Do you know a notary near here?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Send for him!” But Robert, about to go, suddenly whispers: “Look out for his pistol!”

“His pistol! Where is it?”

“He’s got it on, sir,” says the man. “That’s the reason I obey him so quickly.”

“Has he?” says Larchmont, and stepping back into the library, he remarks: “Frank, I’ve got to go out this evening, after I get through my business with you. I left my revolver in Panama. I have got so used to carrying one, I shall not feel safe without it.”

“Oh, take mine!” cries his brother, cheerfully, and he hands him a very impressive looking weapon, remarking casually: “I brought it to coerce the governess, but have lately used it upon mice in the cellar. It will slay a mouse at four yards!” Then a sudden and awful tone coming into his voice, which makes Harry very happy he has the pistol in his own hands, he mutters: “Besides, on the wedding day—after the bride was married—I had thoughts——”

“Thoughts of what?” asks Harry uneasily.

“Thoughts! thoughts!” says the other. “Just thoughts!”

“Won’t you come in to dinner?” suggests the younger Larchmont, anxious to cut short this musing of his brother.

“No, I never dine now. Perpetual Lent with me, mon ami. Perhaps, after all is over, and I have tried everything, I may turn monk! It is well to learn to fast.” Then Franc̗ois’ tone becomes suddenly anxious, and he murmurs: “If I do not do what he tells me, he has threatened to turn me out of here—to turn me into the streets to starve—I—a Larchmont, starve—I—who have never been hungry before! I am educating myself for this.”

“You need have no fear of that now,” remarks Harry confidently. “Here’s the notary.”

And that official being shown in shortly thereafter, Francois Leroy Larchmont assigns his guardianship of Miss Severn to Harry; and Harry acknowledges receiving the fortune of the young lady.

To the first of this it is best to get Jessie’s assent, which she is delighted to give; the notary going up to her to take her signature.

So coming from this interview, telling Robert to send one of the other servants out for a doctor, and to watch at the door to see his brother does not leave the room, Harry Larchmont goes to dinner, with but very little appetite. He has, however, made arrangements for the restoration of Miss Severn’s wardrobe, and that young lady flits down to him, in a very pretty dignified evening dress, though she sometimes pulls down her skirt as if anxious to make it longer, and once or twice takes a look at her train to be sure it is there. As he eats she proceeds to give him further details of the last three days, some of which would make him laugh, were they not additional evidences that Francois Leroy Larchmont has lost the weak mind he had, through his fears of Baron Montez.

An hour after this, a distinguished French physician comes, and after examination tells Harry that just at present these peculiar disorders are so ambiguous, he cannot tell whether the disease of his brother will be permanent, or not. He must study the case for a few days.

“It may be only the nerves—it may be the brain. If the latter, it is probably hopeless! At any event, he must have attendants. He must be watched. He must not be let go out of the house alone. If Mr. Larchmont wishes, he will send him two reliable men.”

“Very well,” says Harry; “I am much obliged to you, doctor. Do as you suggest.”

An hour afterwards, two quiet but determined looking men come.

“Who are these?” asks Francois uneasily.

“Two secret police to guard you from Baron Montez,” whispers his brother.

“Ho, ho! Then we have Fernando!” chuckles Frank as the men attend him upstairs.

Satisfied that his brother will be taken care of, Harry thinks he would like a cigar in the open air.

The night is a beautiful one. He has been accustomed to open rooms on the Isthmus, and to sea-breezes on the steamer. He thinks he can better meditate upon the awful situation in which he is placed, in the open air. He must turn over several things in his mind. Of course his brother’s signature to the document making him Jessie’s guardian, will legally amount to nothing; still, with her consent, he knows a French court will doubtless transfer the guardianship to him.

Then he suddenly thinks of the paper that he has signed, receipting for all of this girl’s fortune—a million dollars—five million francs! He is no lunatic. He is liable for all of it!

He knows that his brother can turn over to him but very little of the orphan’s estate, and he mutters: “I am afraid I have crippled myself! Unless I can force Montez to disgorge, I am now comparatively poor! If I marry, I shall not have wealth enough to retain my position in New York society!”

Then he communes with himself: “There is but one I want to marry, and if she will have me, we can be happy in a flat! I imagine she was living in one when I first met her!”

The servants, tired with their duties of the day, have all gone to bed. Harry hesitates to trouble them. He opens the front door himself, to receive another sensation of this night in Paris.

Almost as his hand is on the door, there is a ring, and as he throws the portal open, he finds himself standing face to face with Louise Minturn—her bosom panting, her eyes bright. She mutters to him: “Thank God, you are here on time!”

Then she thrusts something into his hand and whispers, a frightened tone in her voice: “That will save your brother’s and his ward’s fortune from Baron Montez! Hold to it, as to your life! It contains the secrets of the man you are to fight against! I think I have saved your fortune, but fear I am pursued by the police!”

THE SOMETHING IS THE BULKY, BIG POCKETBOOK OF BARON FERNANDO MONTEZ!

Notes and References

Parker, M. Hell’s Gorge: The Battle to Build the Panama Canal (London: Arrow Books, 2007).

Smith, Fred. R. ‘You Press the Button, We Do the Rest: [,,,] Guide to the newest in the camera bonanza‘, Sports Illustrated, Nov. 1959.

This edition © 2021 Furin Chime, Brian Armour