Some weeks passed. Detective Forster, in his modest office at the Stawell Police Barracks, untied the hessian sack and spread its contents across his desk before Mow Fung. The coat and waistcoat had both been slit cleanly down the back, likely to ease their removal from the body; a white twilled shirt with blue spots, an undershirt, and a fragment of a wideawake hat lay beside them, all stiffened and blackened with blood.

“These were recovered near where the corpse was found,” he said. “I’m showing them around the district, starting with the publicans, to see whether anyone can put a name to them. Ever clap eyes on them?”

“Not easy to say. Clothes are clothes,” Mow Fung said.

“The spotted shirt? Pale hat?”

Mow Fung drew an exaggerated grimace of doubt.

“Not so unusual. Could belong to anyone. You are going down to the Chinese camp after this, I suppose?”

As it happened, that was precisely Forster’s intention.

“What makes you say that?”

“Police always look there first. I hear talk – they say the murder was done in the camp, and the body carried east to where the head was taken off. That ground lies midway between the camp and Stawell – four miles. Convenient.”

He gave a wry smile. “Naturally, it must be the Chinese camp. Many more men live in Stawell – but they are good white men.”

“No call to get prickly, is there? There have been disturbances in the camp. It draws the rougher element, that much is certain. I can’t say I blame a man for drifting there. There’s precious little diversion in the bush.” Forster, Melburnian by origin, retained something of the city’s broader tolerance.

“Who is to say the owner is the same?” Mow Fung said. “Blood on shirt and vest – but none on trousers. They were not discovered together, correct?”

“I believe I am the one paid to ask questions,” Forster said mildly, “but there is no harm in your knowing that they were not found in the exact same place. I recovered the trousers roughly four hundred yards from the body and the other items.”

“The blood on the coat is faint. There has been little rain of late. It may be animal blood, or human. We shall never know. Anything is possible. But if the murder were done in the Chinese camp, why take the body east toward Stawell to dispose of it, when there are many deep mines much closer to the west?”

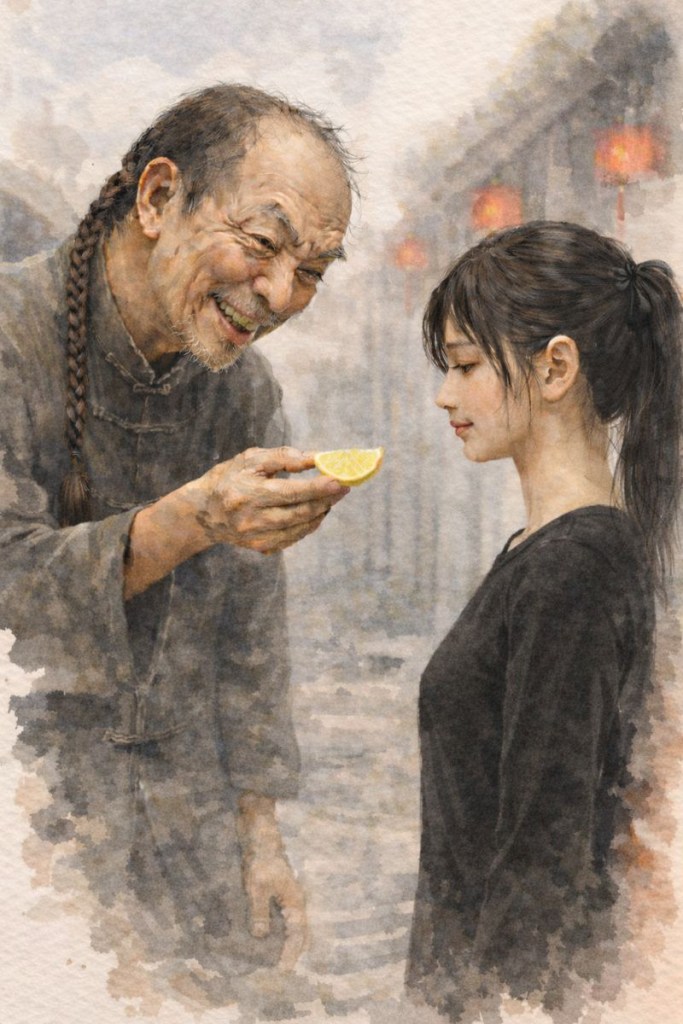

“A reasonable observation. Still, someone in the camp may have seen these garments before, when their unfortunate owner was still walking about in them. If you are heading home, I wonder whether you might accompany me to one or two establishments there – since you were good enough to lodge the deceased on behalf of the Victoria Police. That is, if your good lady would not object to your being away from business a little longer.”

“Why do you want me to come?”

“Only that you’ve got more English than many of the men down at the camp, and some of them are apt to clam up – or go to ground – when a policeman turns up. Despite what you say, there may be one or two uneasy consciences there.”

“Perhaps some understand English better than you suppose, but prefer not to speak to policemen.” He glanced at Forster’s plain clothes. “It is wise not to wear the uniform – it softens the impression. My wife will manage the pub. I had intended to return as I came – on Shank’s mare, as they say.”

• • •

Forster drove them out of the township in a trap, along the track, through the dust and glare beneath the blazing sun. The landscape grew strange once the town fell behind them and its ordered shapes yielded to the scrub. Each, sooner or later, noticed the black mat of flies on the other’s back, where they pressed and jostled to feed on sweat and the salt of human skin, in their obscene communion. Best to leave them; disturb them and they rose in a thick, droning swarm.

The dull thud of the horse’s hooves, the creak of the trap, and the rattle of the harness were swallowed by the silent bush, as though sound itself were absorbed into the vast, listening earth. Holes appeared in patches of bare orange soil already surrendering to growth – the signs of earlier incursions. Here and there, mounds of excavated dirt lay heaped about deepening shafts, like oversized crab-castings along a shore. The human crustaceans who dug here twenty or thirty years ago were gone, many returned to the earth whence they came, having taken what was of value and left their detritus here. Thus history ends where it begins. Or only in these parts?

The two continued along in a silence punctuated by the discordant cry of a single bird.

“Did he say ‘Ballarat’?” Mow Fung said with a delighted start.

“Not too far from home, enjoying his day-trip like us, maybe.” Forster chuckled. Grey butcherbird, probably. He had read that places were sometimes named for the cries heard there. “They say that Ballarat means ‘resting place.’”

“Those shafts are Chinese ones,” Mow Fung said. “Round holes with no corners for evil spirits to hide in. Also, round is better than square, because the sides won’t fall in so easy, and you don’t need much timber. A European does not have to worry about ghosts and spirits, does he? Too rational for them, so they cannot harm him,” he added with a small laugh.

The camp’s heyday lay twenty years past, when gold gravel was struck midway between Stawell and Deep Lead, one of the richest alluvial fields in Victoria. Before long most of the gold was taken, leaving only enough to sustain a dwindling community of oriental fossickers. Of late, the diamond drill had kindled hopes of renewal, and the New Comet Company had even set up in Deep Lead; yet a recent regulation barred Chinese from employment on non-Chinese leases.

“A rough, strongly built man – there are many such men working on the railway these days,” Mow Fung mused. “If he is not known in Stawell, then he must have come from elsewhere, perhaps to work on the new line.”

“They are indeed a transient breed.”

Shops and dwellings huddled together, walls and a variety of roofs clad in boards all askew, yet which somehow in their chaos attained a harmony all their own; frail but sound constructions lining a street not wider than a cart track.

To Forster, this time too, everything seemed Chinese, from curious fabrics and wares in the windows to the cats and dogs yawning and scratching in patches of shade. Mow Fung exchanged a few words in his own tongue with a plump, amiable woman shaking a mat as Forster pulled up the rig. Her two infants played with a top in the dust at her feet and squealed in high, lilting tones, miniature editions of their mother. The newcomers stirred a hubbub in the nearby buildings, and within a minute a dozen Celestials had poured out and gathered around the trap to inspect the garments Forster had displayed on the seat, while he fended off the more enthusiastic who reached to handle them.

“Nobody recognizes these things,” Mow Fung said.

They proceeded down the street, Forster leading the horse and trap.

“What a pong. For God’s sake, that’s a great patch of human dung beside that place!”

“Dried out, it makes good fertiliser,” said Mow Fung. “We Chinese have had to learn that practice, because Chinatowns are usually built below the main town, at the bottom of a hill where sewage and rubbish wash down. Very smelly, though. The newspaper editor often worries that diphtheria will not kill us here, but will drift over to Stawell instead.”

They stopped before the joss house, a low timber building with a sloping roof. A faint scent of incense drifted from within. Mow Fung went over to pay his respects, bowing and disappearing through the open door.

“No good,” he said when he came back out, holding a paper lantern. “Somebody knocked off some ritual ornaments. Terrible omen.”

“What’s that you’ve got?”

“Kongming. Sky lantern.”

Forster made a noncommittal grunt. “Right. Say no more.”

Mow Fung shrugged. “My mother used to say, ‘If you want to become full, admit the emptiness.’ Lao Tzu said the same. It means don’t think too much – listen once in a while.”

“Steady on. It’s too hot for philosophy.”

At the far end of the street, a group of men loitered smoking in front of a building.

“Miss Lili Chan’s Jade Phoenix,” Forster said. “Its reputation precedes it, and not in a good way. Sly grog and opium. Fantan croupier of prodigious luck – or suspect dexterity.”

“Good friend. Lady of fine quality,” Mow Fung said.

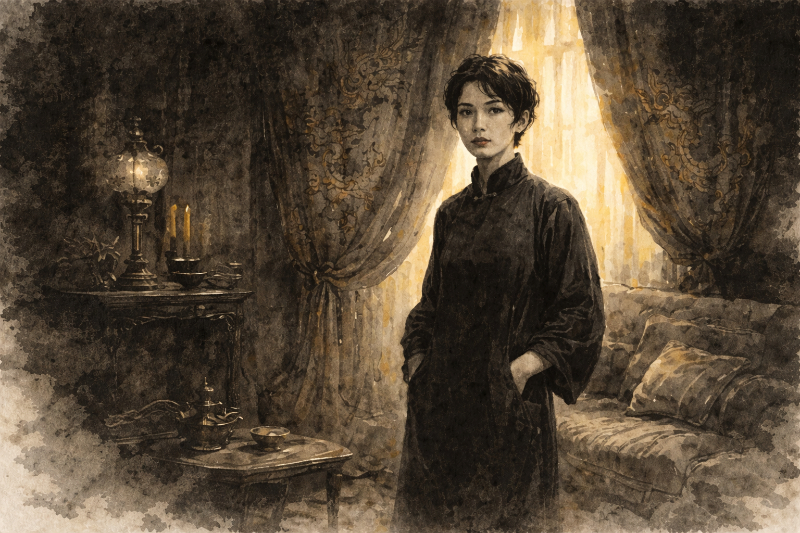

Heavy curtains enclosed the parlour, parted here and there to admit thin slivers of light. As Forster looked about to gain his bearings, portions of the room surfaced briefly before retreating again into shadow. He had been expected; nothing illicit met the eye. A girl seated on the end of a couch plucked on an instrument resembling a pear-shaped lute, producing a languid, elusive strain. Beside her a man leaned with his head slumped insensibly against the shoulder of a young female, who smoked a long pipe and fanned herself with a bored look. Some men sat around a table playing pai-gow with black dominoes marked in red and white, wagering from little heaps of matchsticks.

Lili Chan herself emerged from a curtained doorway in a loose-fitting, mercerised cotton changpao. The matte black fabric gave a restrained rustle as she crossed the room. For an instant Forster thought he saw a light-coloured shock of hair before the curtain slipped back into place. She took a cheroot from a lacquered box on the mantel shelf, inserted it into a cigarette holder and signalled to a brawny attendant to light it for her, before at last addressing the two men.

“Detective Forster,” she said. “I assumed our paths would cross again. I take it this is not a social visit.” With a smile, she nodded to Mow Fung.

“Business has a way of intruding,” Forster said. “Even in agreeable surroundings.” He tapped the hessian at his side.

“Intriguing. Even so, perhaps you will still allow me to extend some hospitality.”

She gestured to a young woman, who brought a small tray with porcelain cups and set it on the low table. Lili Chan took a seat without hurry. After a brief hesitation, Forster and Mow Fung did the same.

Tea was poured from a pot painted with blossoms and winding script. Forster sipped from courtesy; the brew proved lighter than he expected. The murmur of Chinese between Lili and Mow Fung faded into the notes of the lute. Her garment fell in precise folds from her shoulders; the high Mandarin collar framed her face and lent her bearing a formal gravity. A diagonal opening crossed her chest, secured with subtle braided knots. Though the room held the day’s heat, she inhabited a cooler plane altogether. She offered him neither word nor glance, yet he was aware of being measured.

Then the voices were quiet and he heard only the sparse notes of the lute. She drew on the cheroot, inclined her face and, exhaling the smoke through her mouth and nostrils, looked at him fully for the first time.

Forster opened the sack and laid the clothing on the table. “You have seen these before?”

Her eyes moved once across the cloth. “No.”

“You are quite certain. Perhaps someone else present?”

“I do not recognize these things,” she repeated. “Nor do my employees, for I do not.”

At the door, Forster offered her a smile and nod.

“I understand there was some trouble in the camp last week,” he said. “You see much in this street, Miss Chan. If any part of it bears upon my inquiry, I would be obliged to hear of it.”

“The temple was robbed by a vagrant from Stawell, a European. I explained to the priest, Mow Fung, that there was no need for the law. The stolen goods were recovered, and mercy shown. Too much to drink. He returned everything when he sobered up and regretted his deed.”

Outside, Forster turned to his companion. “Priest?”

Mow Fung looked bashful. “I only consecrate a few things here and there, make rain, tell fortunes, guide the dead, heal boils, such matters…”

• • •

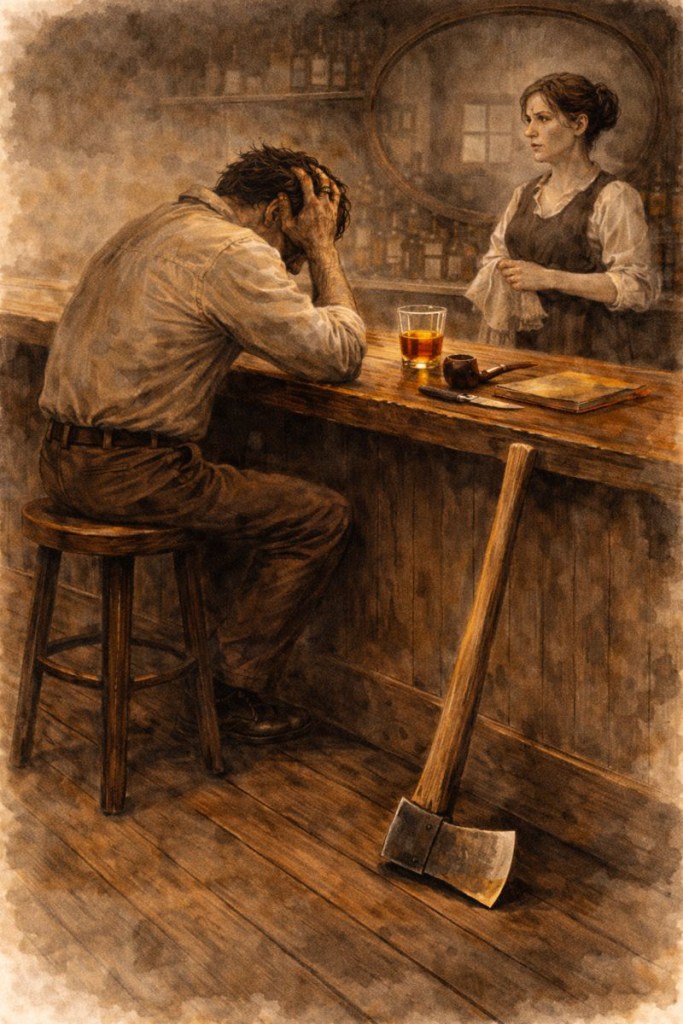

Forster found John Campbell, publican of the Royal Hotel at Glenorchy, in his back office. He placed the sack on the table and took out the clothes, one by one. Campbell watched without moving, then gave a short, humourless snort.

“I know these,” he said. “I’ve seen them worn.”

Forster waited.

“Two railway hands, December – navvies off the Dimboola works. Twelfth to the fourteenth, in the one room. Burns was one – smooth-tongued. His mate called himself Charley Forbes. Big red-bearded fellow. ‘Scotty,’ they called him, though he said he was Irish.”

Campbell touched the coat, as if confirming a weight.

“He wore this. Coat and hat – same sort. Burns did the talking. Held the money. Kept him close.”

Forster wrote.

“They came down by train?”

“From Horsham, they said.”

Campbell’s mouth tightened.

“They ran out of money here. Lost it at cards and drank what was left. When it came time to pay for the room, Burns left a watch with my barman as security – said once the debt was met it was to go on to Stawell, care of Phelan, the storekeeper.”

Forster noted the name.

Campbell reflected for a second and added, “I saw Burns at the Stawell races a few days after Christmas. I asked after Forbes. Burns said he’d gone up to New South Wales with an old mate.”

Forster gathered the clothes together.

“That’ll do,” he said. “And if you’re pouring, I’ll take that whisky now.”

• • •

A few days later, Forster reached the railway camp outside Dimboola, closing in on his phantoms.

“Painter and his son?” Forster said.

“Ain’t here …” the foreman began.

The discharge came with a dull whomp! – sudden and overwhelming, as loud as a cannon, yet muffled by the tons of dirt and rock. The vibration struck the stomach as quickly, if not quicker, than the eardrums. Forster jumped and got through the “Holy–” before tons of dislodged rock thundered down out of sight around the bend.

“… Jesus!” He blanched and stepped quickly into the cover of the embankment, underneath which a line of navvies was gathered in loose formation, with some standing and others seated in the dust or on rails and stacked sleepers. A drizzle of stones pattered beyond the shelter of the embankment and a cloud of dust surged round the bend. A few seconds of silence followed, the men watching the detective regain his bearings.

“Who’s opened his bloody tucker bag?” one of them drawled, earning a chortle or two. Forster looked over and was met by steely, sullen faces and a few grins bordering on sneers.

“Should’ve mentioned that,” said the poker-faced foreman. “Bit of blasting this morning.”

Evident the copper was put out. Didn’t much enjoy being the butt of a joke.

“The detective is lookin’ for the Painters?” he called. “Where are they?”

“Morning off,” came a reply. “Doubler yesterday.”

A whistle-blast came from around the bend.

“You men get back to work now,” the foreman said.

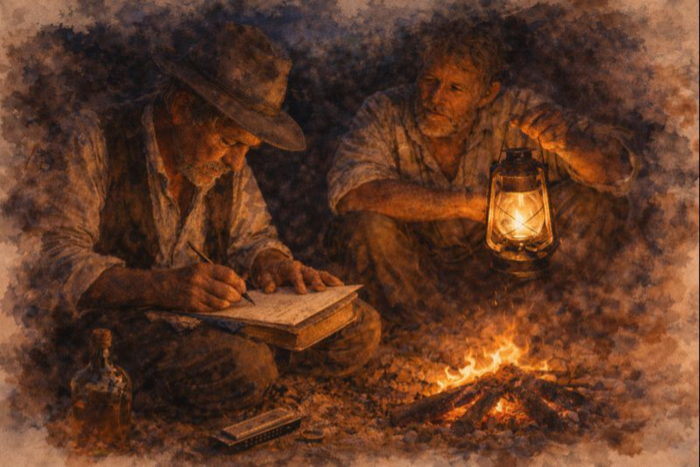

He showed Forster to one of the tents at the workers’ campsite some hundred yards off. Two men dressed identically in grimy singlets and shorts, Richard and John Painter, father and son, sat on stools drinking tea, either side of an upended wooden fruit box that served as a table.

At Forster’s direction, they examined the clothing, identical smokes drooping from the corners of nearly identical mouths. Coat in two pieces, almost the same colour as the grass in which it had been found. Waistcoat also in two halves, the buckle and strap suggesting it had been quite new before lying exposed for a month or more. The blue twilled shirt, comparatively new, a button torn out – that button found in the vicinity. Relics of the wideawake hat. All the garments except the wideawake more or less saturated with what looked like blood. He had not brought the trousers, which were found down a mine shaft some distance from the body; he reckoned they were probably the dead man’s too. Less distinctive, though; harder to identify positively.

The Painters hummed and harred, seeming to communicate to each other in their own language of undecipherable mutters and growls, scratching their beards and shaking their heads deep in thought. The detective waited. Just as his nerves began to wear thin, the two men sucked in a breath as one, glanced at each other over their cups of tea, and shook their heads.

“Yep,” said the elder.

He opened his mouth to continue.

“Teeth, Father. Company. Manners.”

Painter the elder fumbled for his dentures on top of the fruit box between them, alongside some grimy playing cards, three battered tin cups – two half-filled with tea – an overflowing ashtray, and half a browning apple.

“Reckon we know this bloke,” the father said. “Or knew him, you might say.”

“The feller who owns these here clothes,” the son said. “Know him pretty bloody well. Knew him.”

“Worked with him, God rest his soul,” the father said. “Nice chappie, broth of a boy. Bit slow. Addicted to the drink.”

“Never once saw him drunk, Father.”

“Never seen him drunk? You must be jokin’.”

“Who said he’s dead?” Forster said.

“Been reading the papers, that’s all. The body at Four Posts,” said the son. “Terrible thing, shocking. Must’ve been him.”

“What was his name, then?” Forster said.

“Scotty, they called him,” the son said. “But Charley Forbes was the proper name.”

“Charley Forbes,” the father agreed. “Charley Forbes.” Tutted.

“You’re certain these belonged to Charles Forbes?”

“We know this coat by where it’s mended,” the father said. “This bit of stitching on the breast here.” He pointed a finger, the hand had a slight tremor in it now.

“This here stitching on the breast,” the son said. “Charley burnt a hole in it with his pipe, so he stitched it up like this. Couldn’t be more certain it’s the very coat. I never saw him burn it, but I saw it stitched.”

“Not a bad piece of stitching, really,” the father said, bending closer. “Quite sure as to the identity of this coat. No question.”

“No question,” said the son. “Ain’t seen him since him and Burnsey took off together, a bit before Christmas.”

“What’d he look like?”

“Broad-shouldered, stout fellow. Large, flowing beard.”

“Well, light sandy coloured, I’d say. Beard was lighter than the hair on his head, which was a dark sandy colour.”

“Yeah, I s’pose you’re right there, Father. Light sandy coloured beard. Dark sandy coloured hair on his head.”

“Sandy complexion, wouldn’t you say, Son?”

“That’s right, Father, very sandy.”

“And this other character, his mate?”

“Robert Burns,” said the son. “Like the Scottish poet.”

“That Man to Man, the world o’er, Shall brothers be for a’ that,” quoth the father, and lapsed into vacant thought, his head nodding involuntarily.

“Old Jake seen him over at Murtoa the other day, getting off the train,” the son said.

“Burnsey?” Forster said. “Where’s this Jake?”

“Shot through.”

“Where to?”

“Goodness bloody knows. Just cleared out the other night.”

From the draft novel Stawell Bardo © Michael Guest 2026