Followed by his colleagues from the Peers’ School, Mushanokoji began publishing Shirakaba in 1910, which was to become the most important literary magazine of early twentieth century Japan. He had graduated from the Peers’ School, then withdrawn from Tokyo Imperial University in 1907. Shirakaba means “White Birch,” in reference to the white birches that appear plentifully in Japan, but are even more overtly symbolic in Russian literature.

This post in the Exploratory Companion will sketch out elements of the literary and lived forms of Mushanokoji’s evolving humanism, from his Tolstoyan beginnings, through Maeterlinck, and culminating in his literary philosophy and social experiment at Atarashikimura village. I aim to explore the broader global context for his development. It’s not only via his attachment to the metaphysics of Maeterlinck that THE INNOCENT speaks so accessibly to modern readers, nor only through its avant-garde characteristics, but also because of his position in this ongoing historical movement of “East-meets-West” humanism and peace.

Rousseau – Tolstoy – Gandhi: evolving world vision

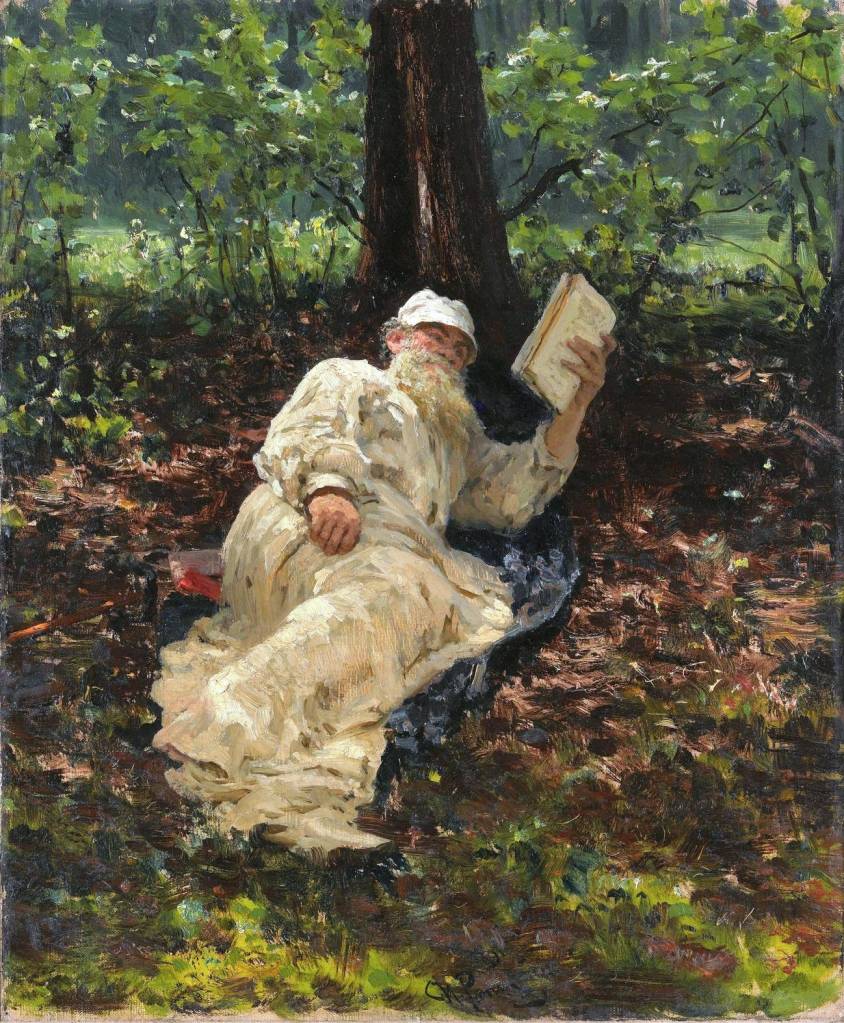

The title Shirakaba resonates with the influence exercised upon the young Meiji intelligentsia by the great Russian author Count Leo Tolstoy (1828 – 1910), through ideas communicated to them by Mushanokoji himself. This influence extended not only to the field of literature but also into social and community idealism, and Mushanokoji’s founding of the village of Atarashikimura, to embody his ideals and teachings. (Rekolektiv, “Atarashikimura in Interwar Japan”).

To outline the origins of a broader humanistic movement of which Mushanokoji’s work is one manifestation, we would look to Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 –78), whose critique of social inequality and ideas about education and the nature of humanity captivated Tolstoy from the age of fifteen. The opening up of a secluded Japan and its potent interaction with Western culture during the Meiji period provided fertile ground in which these ideals could evolve in a fascinating direction.

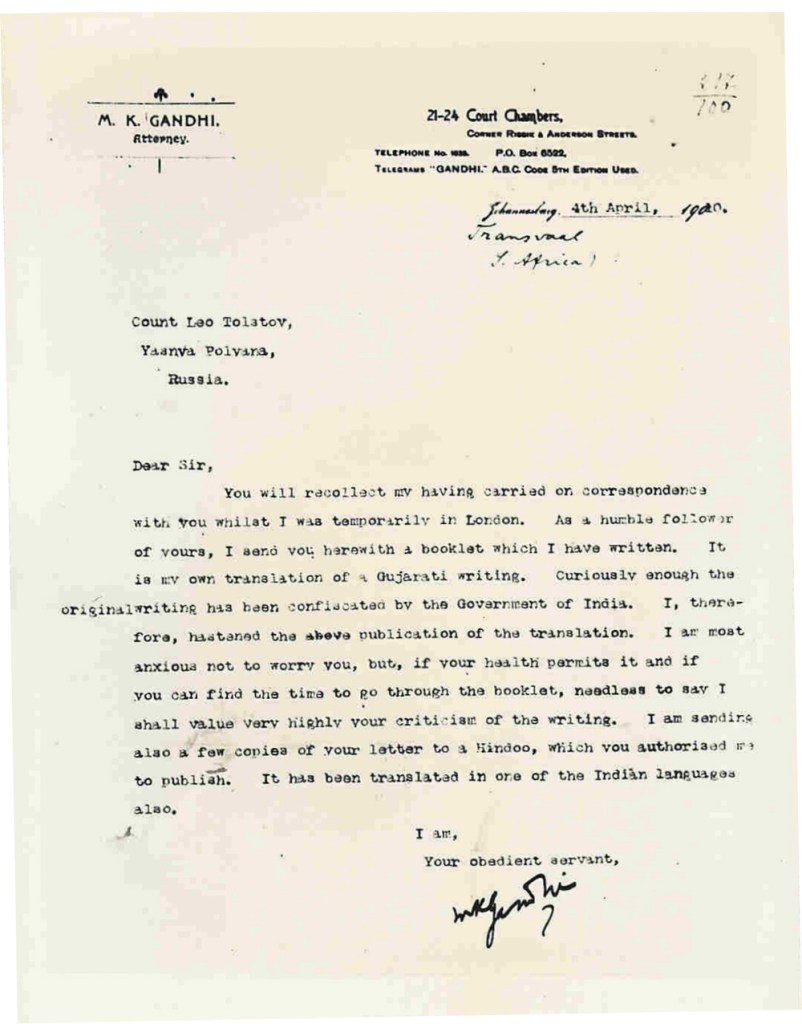

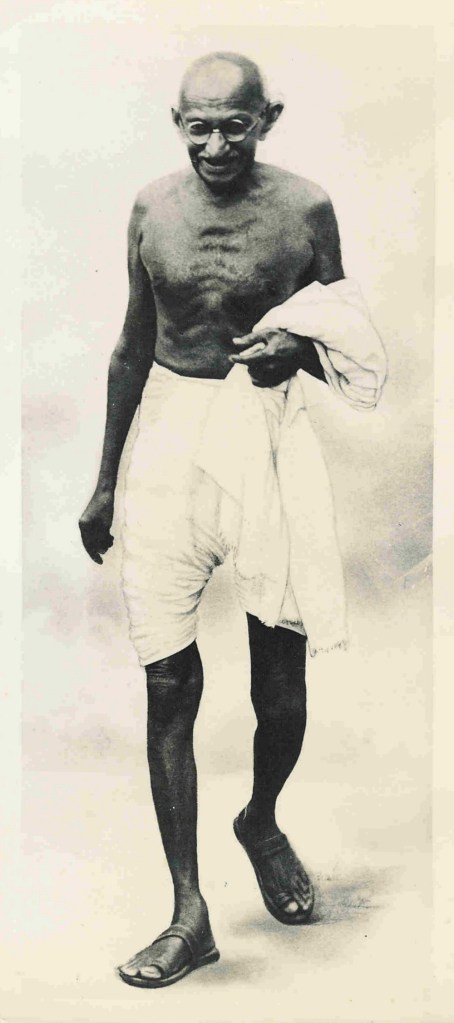

Tolstoy’s contribution to the broad politics of peace and non-violence was, of course, immense, and magnified through his relationship with Mahatma Gandhi (1869 –1948). In his autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth (1925-29; 161), Gandhi wrote that he was “overwhelmed” by the Russian’s reinterpretation of Christianity, due to its “independent thinking, profound morality and […] truthfulness.”

Tolstoy’s 1908 “A Letter to a Hindu” instigated an ongoing correspondence between the two great luminaries. In 1910, the Mahatma established a cooperative settlement in South Africa, naming it Tolstoy Farm, which was to be a model for self-sufficient, communal living, and training in satyagraha — a commitment to truth, non-violence, self-suffering, courage, conviction, and self-discipline.

Aristocratic obligation and presumption

The youngest of eight sons of a Japanese Viscount, Mushanokoji turned to Leo Tolstoy for literary and humanitarian inspiration, fueled by a sense of social obligation that inhered in his aristocratic birthright. During what is sometimes called his “Tolstoy craze” late in his adolescence, Mushanokoji had emulated the ascetic lifestyle that Tolstoy espoused, by living in a small, unheated hut on his family’s estate, “wearing simple clothes and leaving the stove unlit.” Indeed, because of their privileged origins, Mushanokoji and his Peers’ School colleagues received criticism in Japan as being immature and dandyish dilettantes, despite or perhaps even because of the charitable acts that several of them exhibited in response to social inequality, such as Arishima Takeo, who gave his family farm in Hokkaido to its tenants as cooperative owners (Yiu 218).

Mushanokoji’s uncle provided his nephew with recently translated Japanese editions of Tolstoy’sThe Kingdom of God is Within You (1894) and other works by Tolstoy, and also introduced him to the Bible:

Mushanokoji’s host – his reclusive uncle Kadenokoji Sukekoto – was far from fashionable. After suffering a series of financial setbacks, Kadenokoji had retired to live alone on his sole remaining estate. He worked in his fields in the daytime and spent the evenings studying sacred texts and discussing them with Christian pastors and Buddhist monks. His eclectic spirituality set an example for his nephew, who would also spend his life gathering ideas from diverse sources.

Anna Neima, The Utopians: Six Attempts to Build the Perfect Society (118).

Mushanokoji was indeed greatly inspired by Kadenokoji. It is unlikely, however, that the compassionate and amusing portrait of Jibun’s uncle in Chapter 7 of THE INNOCENT is specifically him, since he died from kidney failure at the age of 65, whereas the uncle in the novella dies from cancer at 45 or 46. Recall, however, that Jibun’s father appears in the novella, even though the fact is he died when the author was an infant; so the possibility remains that Jibun’s uncle may be based on Kadenokoji.

It is perhaps fairly natural to suspect the compassion that privileged individuals extend to those below. For some, the image of Marie Antoinette dressing up as a peasant in her rustic hamlet in the grounds of the Château de Versailles prefigures an inauthentic spectacle of the aristocrat Tolstoy assuming the guise and lifestyle of his peasants, from which he always had the freedom to withdraw.

Not to be too glib, however: Buddha himself, Siddhartha Gautama, was an aristocrat who, in his “Great Renunciation,” gave up his wealth, family, and social status to become a wandering ascetic.

Shadow of Buddha: eclectic spiritual roots of a humanistic ideology

Tolstoy deeply respected Asian culture, and his ideology is redolent with Eastern thought. His interest stemmed from an early experience at age nineteen, when he met a Buddhist monk in a hospital in Kazan, who had been robbed and assaulted violently, but had not fought back, adhering to the principle of non-violence (Kamalakaran).

The encounter had a profound effect on Tolstoy, fostering his lifelong interest in Buddhism and other Eastern teachings. He experienced an existential crisis in his mid-50s, which he described in his autobiographical A Confession (1880), when, after having achieved wealth and fame, he found life lacking in meaning. Tolstoy became disillusioned with traditional Christian churches, believing they had corrupted Christ’s message. While his resulting “new faith” was not explicitly Buddhist, it marked a significant sympathy with Eastern philosophies. (See Kamalakaran, “The influence of Buddhism and Hinduism on Leo Tolstoy’s life” – Russia Beyond.)

Tolstoy engaged further with Buddhism in an 1889 essay, “Siddartha, Called the Buddha, That is the Holy One,” and expressed Buddhist ideas in his correspondence, discussing concepts such as karma and reincarnation. Towards the end of his life, he contributed an article on the Buddha to his anthology “The Circle of Reading” (1906) and translated the American Paul Carus’s (1852 – 1919) story “Karma” into Russian.

His adoption of vegetarianism, championing of non-violence, and attempts to live a simpler life demonstrate an affinity with Buddhist practice. Ultimately, the philosophy he developed, known as tolstovstvo, containing a core concept of mankind living in peace, harmony, and unity, and which also encompassed his rejection of luxury and opposition to the exploitation of peasants, is in keeping with Buddhist ideals.

Subsequently Tolstoy engaged in further Japanese projects, particularly in the context of agrarian and utopian movements. He collaborated with Konishi Masutaro, a Japanese Orthodox priest, on a translation of the Daoist text, the Daodejing, which they both saw as “an escape from state authoritarianism” and a step towards a “‘new universal religion’ based on Tolstoyanism” (Johnson, “Displacements: Current Work on Japanese Modernism”). Tolstoy’s concern with the peasantry and agricultural reform became a significant legacy in Japan, influencing movements described as “agrarian-Buddhist utopianism” (see Shields).

Mushanokoji explored Buddhism explicitly to some extent in later life, presenting the Buddha as a “human” ideal in his popular work Life of Shakyamuni Buddha (1934; ctd. in Shields). Mushanokoji’s explicit intention here was to emphasize the “human” Shakyamuni, portraying him as an ideal figure lauded for his insight and compassion, someone who possessed a natural innocence, described as “the heart of a child” (akago no kokoro). He portrays Buddha as a valuable model for human behavior, one stripped of mystical elements. Mushanokoji included Shakyamuni Buddha in a pantheon of “masters” alongside Jesus Christ (whom he saw as a “man with a pure, pure heart”), philosophers, writers, and even literary characters, all of whom served as models of human “liberation” (Shields).

…“the Buddha” functions [for Mushanokoji] as a representative of a complex of humanist ideals, including a religious understanding rooted in common sense and compatible with modern science, one that rejects social discrimination and institutional hypocrisy, and looks to nature itself as a source for liberation.

Shields, “Future Perfect: Tolstoy and the Structures of Agrarian-Buddhist Utopianism in Taisho Japan”

Mushanokoji’s utopian vision thus blended liberal-humanist ideals evolved from Buddhist, Christian, and Western philosophical traditions. Shirakaba writers compiled a list of idealist “masters” whom they admired, including Christ, Buddha, Confucius, St. Francis, Rousseau, Carlyle, Whitman, and William James. Interestingly, in her book, Meeting the Sensei: The Role of the Masters in Shirakaba Writers, Maya Mortimer asserts that in rejecting all (positivistic) “-isms,” the Shirakaba “masters” embody a “way of unlearning” or a Zen-like methodology (ctd. in Shields).

Subversive philosophy of self-love

In an explicit doctrine of egoism (jiko shugi), Mushanokoji advocated one’s complete subordination to the Self:

Our present generation can no longer be satisfied with what is called “objectivism” in naturalist ideology. We are too individualistic for that . . . I have, therefore, taught myself to place entire trust in the Self. To me, nothing has more authority than the Self. If a thing appears white to me, white it is. If one day I see it as black, black is what it will be. If someone tries to convince me that what I see as white is black, I will just think that person is wrong. Accordingly, if the “self” is white to me, nobody will make me say it is black.

Mushanokoji, “Art for the Self” (1911), qtd. in Shields

THE INNOCENT brilliantly embodies such a subjective gesture. In what I have called Jibun’s “spiralling inwards,” he is drawn towards the phantasm of his beloved, the girl Tsuru. That is, she is rendered as a symbol of an ideal love, which is ultimately perceived as his love for himself, which he realizes he is unable to sacrifice for her sake (See previous posts and Translator’s Preface to THE INNOCENT).

As discussed in previous posts, Mushanokoji’s humanistic perspectives were greatly influenced as well by the Belgian writer and philosopher Maurice Maeterlinck, with a primary emphasis on self-love and the cultivation of the individual self. Mushanokoji declared in an early issue of the Shirakaba journal, on the struggle of attaining a free individuality:

I only understand myself. I only do my work; I only love myself. Hated though I am, despised though I am, I go my own way.

Mushanokoji in Shirakaba (1912), quoted in Gennifer Weisenfeld, MAVO: Japanese Arts and the Avant-Garde, 1905–1931 (Berkeley, CA; Los Angeles, CA; London, 2002), 22

Thus Mushanokoji’s thought evolved in a direction away from the ideal of self-sacrifice associated with his earlier Tolstoyan influence. Maeterlinck’s metaphysical vision validated an insular, contemplative life. It equipped Mushanokoji to make a literary inward turn to autobiographical fiction and to embody the inner trajectory in literary form.

A brilliantly original achievement in THE INNOCENT lies in how the author explores multiple implications of such an introjection of objective reality, preserved ironically in an accessible naturalism. In so doing, Mushanokoji adapted Maeterlinck’s philosophy of self-love, encouraging individuals to conduct themselves as individualistic moderns, living for their own pleasure, and writing about the process of exploring their own natures. Mushanokoji came to adopt a pivotal point of opposition between Tolstoy and Maeterlinck: that we must love ourself in order to love others:

In an essay titled Jiko no tame oyobi hoka ni tsuite (For My Own Sake and Other Things, 1912), [Mushanokoji] paraphrased Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949) and wrote, “Even if you were told to love your neighbor, you must first learn to love yourself. Moreover, it is not sufficient to love your neighbor as you love yourself. You must love yourself in others”

Mushanokoji “For my own sake and other things” (1912), qtd in Angela Yiu, “Atarashikimura: The Intellectual and Literary Contexts of a Taishō Utopian Village,” Japan Today

Mushanokoji’s exploration of identity and self-cultivation in THE INNOCENT and later writings became a key early expression of a cultural phenomenon of the time — a so-called “cult of self-love.” It became a popular mindset among Japanese youth, even prompting government concerns. School texts were rewritten, with the idea of preventing hedonistic individualism from undermining loyalty to the state. Conservatives fumed that Western ideas were destroying Japan’s social cohesion, and that traditional values of piety and loyalty had to be revived (Yiu).

“Twin Desires”: I-novel and village utopia

Atarashikimura can be read as the continuous augmentation of an ego that seeks to make its impact felt not only on the pages of a book but literally on earth. The village, like his art, is created “for the sake of the self ” (jiko no tame), and is thus the ultimate act of self-expression.

Angela Yiu, “Atarashikimura: The Intellectual and Literary Contexts of a Taisho Utopian Village.”

In 1918, in an effort to embody his ideals and teachings, Mushanokoi established a utopian village community in Japan: Atarashikimura (“New Village”). Mushanokoji’s social project was in the spirit of Tolstoy’s school for peasants at his estate of Yasnaya Polyana (“Bright Meadows”) (Rekolektiv). Atarashikimura can be described not merely as a social experiment but as an instance of an “I-novel” sensibility given physical form: “Atarashikimura is an I-novel written not in the pages of a book but in an actual geographical dimension” (Yiu). Still operating today, though relocated from its original site in Miyazaki prefecture to Saitama prefecture in 1939, the village embodies Mushanokoji’s egoistic and creative vision. It’s about an hour and a half from Tokyo.

Today, the village continues to operate based on original principles of communal living and the pursuit of art and culture, fulfillment of each individual’s destiny, and the importance of each person’s individuality. Residents, currently numbering around twenty, contribute six hours of compulsory labor per day. (Members living outside the village can contribute funds.) The remaining time is for the free pursuit of truth, virtue, beauty, and personal interests aimed at actualizing one’s authentic self. Villagers receive an allowance from a collective fund for their daily needs (see Yiu).

When Mushanokoji founded Atarashikimura, during the late Meiji and Taisho eras, or from around the end of the nineteenth century to the mid-1920s, a period in Japan saw the rise of kyoyo shugi, an emphasis on holistic personal development, intellectual cultivation, assimilating ideas from Western humanism, which influenced groups such as the Shirakaba-ha. The concept can be translated as “liberal arts” and is linked as well to the German concept of Bildung, which emphasizes intellectual and personal self-cultivation. Alongside this development at the time was a growing exploration of the inner self, as propounded by Mushanokoji.

The I-Novel and Inner Exploration

Crucially, this period also witnessed the emergence of the I-novel (shishosetsu), a genre of which Mushanokoji’s THE INNOCENT is a seminal exemplar. The I-novel is characterized by its intensely self-oriented nature and the cultivation and assertion of the ego as the ultimate authority. The I-novel marks a strong focus on interiority in fictional writing, as we see clearly in the case of THE INNOCENT, with the novella’s single-minded exploration of identity and self-cultivation.

Angela Yiu describes how Mushanokoji’s aspirations in literary art and his wish to create a new world, a utopian community, were his “twin desires,” such as he expressed in his 1921 autobiographical novel Aru otoko (A Certain Man). In an article entitled “Art for Oneself” (1911), at around the same time as THE INNOCENT, he wrote: “I go all the way to create art for the sake of oneself.” The thought process of Jibun in THE INNOCENT demonstrates his arrival at this same conviction of Mushanokoji’s: a sentiment that extended to his village project. Atarashikimura can be viewed as “[Mushanokoji’s] most invested work of art, a sakuhin {work] that is created for the sake of maximum self-expression” (Yiu).

“Imperialistic Egoism” and the Village

Saneasu Mushanokoji’s philosophy involves a complex blend of influences, including a tension between his declared admiration for Leo Tolstoy and a contrasting development of what Yiu calls an “imperialistic egoism.” In THE INNOCENT, the ego is clearly presented as undergoing an all-encompassing expansion, to the extent that even the beloved character Tsuru is beyond actual reach, but merely an internal phantasm. In attempting to mitigate such an extreme degree of aggrandizement, we may bear in mind Maeterlinck’s own formulation from his book Wisdom and Destiny (1898):

Tolstoy’s ideas on humanism, equality, communal living, and labour profoundly influenced Mushanokoji throughout his life, though Mushanokoji selectively adopted or reinterpreted these ideas to accommodate a philosophy centered on the assertion and cultivation of the self, as advanced by Maeterlinck. Mushanokoji’s is a more progressive ideal than Tolstoy’s, validating aspects like

[…] lust, sex and pleasure-seeking as essential, even moral, components of human existence … This new philosophy of hedonistic egotism was the second of the two strands that Mushanokoji would eventually weave together to form his utopian ideology, combining it with the socially minded influence of Tolstoy and Christ.

Neima, 125

In Chapter 5 of THE INNOCENT, a still “prudish” Tolstoyan Jibun debates the opposition with his libertine, Maeterlinckian visitor:

“You speak from the female perspective, as one would expect from a prude,” he said. “But a healthy man has rights as well. Someone who takes pleasure in life is entitled to do so, without having to go around like some kind of sexual invalid. You, as a scholar, should not derive satisfaction from the plight of the weak. I will not accept the idea that healthy people should be condemned for complying with the demands of nature and enjoying themselves.”

Mushanokoji adapted the philosophy of self-love into a literary philosophy focused on exploring the transcendent extent of one’s own self. His celebration of the self is a crucial element reflecting his philosophical evolution during the period leading up to THE INNOCENT. A model of the Japanese I-novel genre, the novella is marked by an overwhelming emphasis on the subjective perspective and assertion of the ego.

The concept of what Yiu calls Mushanokoji’s “imperialistic egoism” may be further debated in the context of his utopian commune, Atarashikimura. She argues that the village can be read as a physical manifestation of a creative ego seeking to “make its impact felt not only on the pages of a book but literally on earth.” For Yiu, this strong sense of self implies eliminating the difference between self and others by “subsuming others under an overpowering self”. The observation aligns with Mushanokoji’s assertion that “there is no authority above the self.“

The idea of a central “self” encompassing or projecting onto others within the communal setting resonates with the theme of solipsism found in his literary works. This is particularly so inTHE INNOCENT, in which the narrator reduces the figure of the “other” (his beloved Tsuru in this case) to a mere projection of “projection of fantasies and desires, entirely lacking in agency (Lippit, 14).

In his Topographies of Japanese Modernism, Lippit considers that Mushanokoji’s “discursive rendering of the relationship between self and other,” where the Other is reduced to a “phantasmal image,” not only provides a framework for Mushanokoji’s fiction, but also his “consciousness of modern culture” (Lippit 14). The village, as Mushanokoji’s “most invested work of art […] created for maximum self-expression” and an I-novel written in a “physical reality,” reflects this same tendency for the individual self to be the ultimate frame of reference, potentially overshadowing the independent reality and experiences of others.

The concept of “imperialistic egoism” encapsulates a fascinating paradox within Mushanokoji Saneatsu’s work: the transformation of personal idealism into a broader social project. In the I-novel form, this egoism seems not only ideologically tenable but formally generative — THE INNOCENT thrives on the inward-turning journey of the self, with its solipsistic implications often turning into a source of ironic humor. The exaggerated isolation of the protagonist, driven by self-absorption, becomes a way of exploring human vulnerability, and this humor lends the text a certain playfulness while deepening the existential weight of its themes.

However, when these same “imperialistic egoism” impulses are extended into the practical framework of Atarashikimura, their implications seem less straightforward. The utopian vision powered by a single, dominant self could, at least hypothetically, run the risk of reproducing some of the hierarchical dynamics it was meant to challenge. The tension between the ideal and the real seems to suggest that what enables the author’s literary world — the expansive self — might not seamlessly translate into a sustainable communal project. It remains uncertain whether this “imperialistic egoism,” when enacted outside the literary realm, would promote true cooperation or potentially veer into paternalism, revealing the complex balancing act between idealism and pragmatism that such a project sets in play.

Notes and further reading

- Saneatsu Mushanokoji, The Innocent (1911).Trans. Michael Guest

- “Atarashikimura in Interwar Japan” Rekolektiv blog

- Carus, Paul. (1896) Karma : a story of early Buddhism (Chicago: Open Court). Copy at Internet Archive.

- Gandhi, M.K. (1927) An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth Ahemadabad: Navajivan Mudranalaya. PDF freely available.

- Harak, Ed. G. Simon. (2000) Nonviolence for the third millennium: its legacy and future. Mercer U.

- Johnson, R. S. (2023) “Displacements: Current Work on Japanese Modernism“, in Modernist Cultures 18.1

- Kamalakaran, Ajay. (2014). Looking east for guidance: The influence of Buddhism, Hinduism, and Taoism on Tolstoy’s life, “Russia Beyond the Headlines.”

- Lippit,, Seiji M. (2002). Topographies of Japanese Modernism, NY: Columbia UP.

- Mortimer, Mayer. (2000). Meeting the Sensei: The Role of the Masters in Shirakaba Writers. Brill.

- Neima, Anna. (2021).The Utopians: Six Attempts to Build the Perfect Society. London: Picador.

- Shields, Mark. (2016). “Future Perfect: Tolstoy and the Structures of Agrarian-Buddhist Utopianism in Taishō Japan.” Religions 2018, 9 (5), 161

- Tolstoy, Leo. (1894). The Kingdom of God is Within You. NY: Cassell, 1894. Gutenberg copy.

- Tolstoy, Leo. (1940). A Confession / The Gospel in Brief / What I Believe. London: OUP. Internet Archive copy.

- Weisenfeld, Gennifer S. (2002) MAVO: Japanese Arts and the Avant-Garde, 1905–1931. Berkeley, CA; Los Angeles, CA; London. Available on Internet Archive. PDF freely available

- Yiu, Angela. (2008). “Atarashikimura: The Intellectual and Literary Contexts of a Taishō Utopian Village.” Japan Today 2008, 20: 203–230. PDF freely available.

Gandhi Image citations:

Press Information Bureau, “Gandhi (Full Length Portrait),” UHM Library Digital Image Collections, accessed May 11, 2025, https://digital.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/items/show/27516.

Press Information Bureau, “Letter to Tolstoy,” UHM Library Digital Image Collections, accessed May 11, 2025, https://digital.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/items/show/27528.