Honourable Buddhist scholars leave the East and go West. Mr Daruma, who doesn’t like Buddha, leaves the West to come East. I thought they might meet at the Teahouse of Awakening. Alas! It was only a dream.

⁓ Japanese Zen monk Gibon Sengai (1750–1837), adapted.

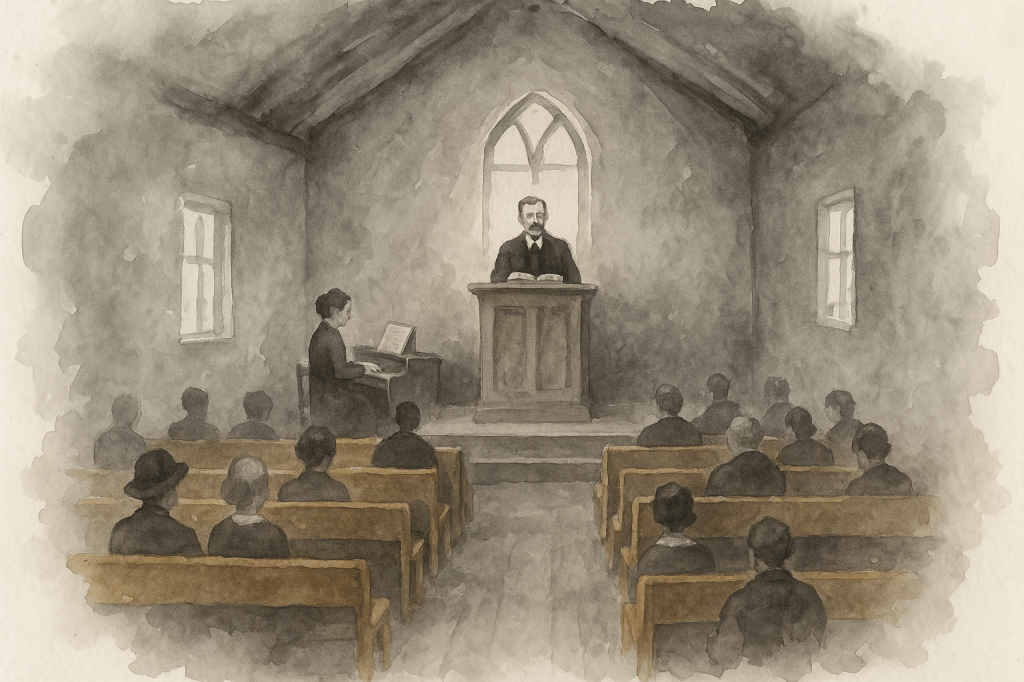

It was Sunday, and a hush had settled over Stawell and its environs, less the product of Christian observance than the fatigue of a community wilting beneath a heatwave. The constables were at rest, their boots airing by the door, while their horses, in the shaded yard behind the lock-up, stood twitching at the flies. Grave-faced publicans bent over their ledgers with a grim focus. And the Reverend Hollins, in his peculiarly tremulous voice and occasional sighs tantalisingly suggestive of a faltering conviction, sermonised to a reduced congregation: a smattering of families, several women in white gloves already thinking of their lunch preparations; a town councillor occupying the aisle-end of the front pew, his straw boater tucked correctly beneath one arm when rising for a hymn, believing virtue to be transmissible through nods, smiles, and a strategic proximity to the pulpit; and indelibly, two boys whose giggles, once stirred, proved difficult to suppress, captive in the back pew, passing between them a folded scrap of paper on which they scratched and scribbled at a caricature of the preacher, recognisable chiefly by the earnest absurdity of his moustaches, while off-key strains of Jesus, Lover of My Soul wheezed from the beloved but dilapidated harmonium.

The shopfronts along Main Street were shuttered, each a mute testament to the Sabbath and the wisdom of retreat. At the swimming hole, boys lay strewn in a loose ring beneath the gums, not so much resting as resisting motion altogether, while their sisters played jacks in the spindly grass nearby, casting now and then a glance at their brothers that combined idle curiosity with frank disdain. They had all been spectators the day before, as Stawell’s cricketers ruthlessly dispatched the visiting Ararat team, notorious across the Wimmera competition for their aversion to practice afternoons.

The players themselves had scattered after the match, victorious and vanquished alike, most of them inclined to the drink. By nightfall, it was difficult to tell who had won: the mood had turned to the camaraderie of once-opposing warriors. On the brink of sunset, a few were seen crossing a drying creek bed, stumbling and laughing while arguing a call of leg-before-wicket as if time might reverse itself were the point laboured long enough, while the bottle, wobbling among them, passed hand to hand with the erratic solemnity of an intoxicated relic.

Forster was not at rest on this Sabbath, nor was he attempting rest, which for him had never been a natural state – least of all while that torn bundle of clothing remained stubbornly mute. The scattered remnants of hat, flannel undershirt, trousers, and coat refused to yield the truth he was sure they withheld. During the week he had moved among storekeepers, stablemen, drinkers, and those who passed for bush-hands in that part of the country, collecting fragments of recollection that slipped, often visibly, from possibility into fancy. They revolved in his dreams, these lingering ciphers of some anonymous, ill-treated lost soul: a vest too long for most men, with a single bleached button still clinging to a thread; a coat with its lining turned the colour of the grass in which it was found; a twilled shirt, comparatively new, now torn open at the front and stained along the seams with dirt and dried blood. An unremarkable wardrobe from which to conjure a name.

And it nagged at him that something vital waited to be perceived, if he could only loosen his grip on his habitual, strictly methodical approach to such evidence. That morning, he had reread a marked passage from a volume he carried in his travelling library, an old work by the British physiologist William Benjamin Carpenter, something about knowledge arriving through circuits of which the thinker remains unaware. “Unconscious cerebration,” Carpenter called it. Not instinct, exactly, but a deeper faculty, which underlies reason. It reminded him of something the Chinese publican had said to him offhandedly: that a man may fix his gaze too closely on the fragments of a thing, and so miss the thing itself. Forster, who did not consider himself a mystic, found the idea returning to him incessantly in recent days, like a tiny pebble he could not get out of the sock of his reason. Yet oddly persuasive. The detective was, like Carpenter, a committed empiricist, but it seemed to him of late that a narrow channel might exist between the Western scholar’s rigid concepts and the Buddhist’s drifting brushstroke. Whence come our “hunches,” our “insights,” our “intuition”? he mused as he crunched along, his plain walking stick, little more than a trimmed length of hardwood, tapped lightly at the ground as he pondered. That solution to a problem suddenly flashing into the mind unbidden: whence does it arise? Its quiet elaboration occurring beneath the awareness.

The heat bore down, and without quite intending to, he had taken the red track to Deep Lead. Past the edge of the diggings, smoke exuded here and there in the Chinese camp, tinted with incense. Truth to tell, when entered from this side, alleys leading from the main street bore signs of the dissolution of which the camp was sometimes accused. There were a few grimy, tumbledown edifices, constructed as though from a pack of pub playing cards – among them opium haunts; the area had of late become known for drawing the idle young from miles around. Denizens of an unprepossessing, not to say suspicious, appearance loitered in the shade; yet even so, Forster reflected, there was a loafing, arrogant class of colonial that roamed around the country and might as easily be found lolling and expectorating about the corners of the principal streets in the best Australian cities.

Towards the Junction Hotel end, the outlook was much improved, with a man repairing an eccentrically designed but spotless and sturdy cabin, or watering a vegetable garden; women in loose cotton trousers and indigo tunics, sleeves rolled to the elbow as they stooped and rose, pegged laundry to low-strung lines between sheds. Beneath a couple of pepper trees in a scorched yard, half a dozen children clad in faded cotton shrieked with delight as they played a game of bat and ball. A little further along he spotted Mow Fung’s own eldest daughter Lena, appearing wraithlike in the haze, suspended in a shimmer of mirage. She was some distance off, walking in his general direction along a track that led into the dusty street. As she came nearer, she recognised the detective and offered a pleasant smile and nod, gesturing that she was on her way elsewhere. He paused under the eaves of the Junction Hotel and glanced at the door. And just at that moment the proprietor appeared from around the corner of his premises, wearing his habitual loose trousers and black satin Chinese “melon rind” cap.

Forster settled into one of two comfortable cane chairs arranged on either side of a small table in the corner of the Junction’s exaggeratedly named Tea House, where his acquaintance had guided him with quiet formality. Actually an interior room, it lay beyond public access, tucked behind the family quarters and adjoining a dim little chamber that might have been a storeroom – it was hard to say. Shelves lined the far wall, crowded with potted plants that leaned gently toward the filtered light. The tearoom itself was reached through a plain, easily overlooked door, and Forster had the distinct sense of being ushered into an inner sanctum, not merely for the warren-like route that led him there, but for the subtle change in the publican’s bearing as they entered: an attitude approaching deference, tinged with the protective instinct of a man offering something precious to one who might not recognise it. Perhaps his one or two official visits to the hotel since the post-mortem had earned him Mow Fung’s trust. It was an unintended but welcome result for a city detective newly stationed in the district, slowly learning the elusive protocols of rural trust.

Mow Fung had then excused himself, to attend to some domestic task or other. More finely dressed than on previous occasions, Mrs Mow Fung was seated at a table in the far corner, opposite a woman whose back was turned to Forster; she gave him a quick smile, then turned back to her companion. The two conversed in hushed tones, drifting between English and Mandarin. A lacquered box sat open on the table, its contents laid out with care: long stalks, slender and pale gold, like dried reeds, along with a square of folded silk, an inkstone, and a strip of scarlet paper. They were playing a counting game with the stalks, or as far as he could tell, tallying up accounts. Forster glanced away, thoughts wandering as he looked out at the garden beyond the window. There was Mow Fung with Lena watering a wattle. Even a scene of such trivial domesticity had the power to soothe the soul, within this hush.

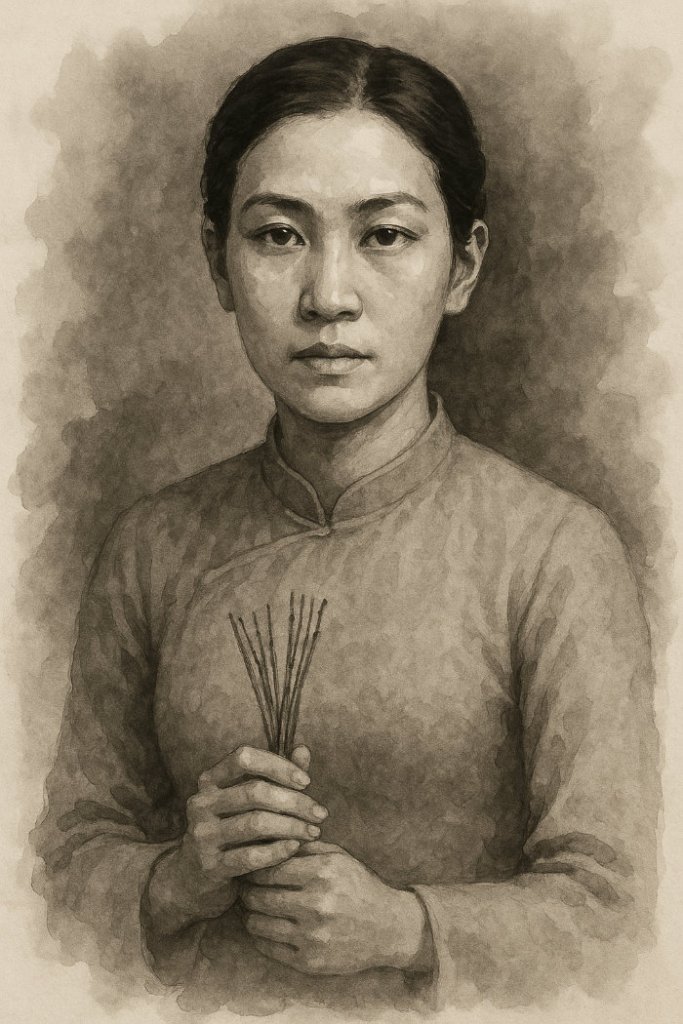

A soft sound drew him back. The woman had shifted in her seat, and he could see her more clearly now: her lissome form and proud profile even with lowered eyes – beauty understated, yet unmistakable. She wore a pale silk blouse, the fabric catching the light just enough to reveal a faint peony motif in the weave; below that, loose, modest dark trousers.

Mrs Mow Fung moved the stalks in her hands while the other woman watched intently, Her elbow rested on the table beside the inkstone box, fingers idly tracing its lacquered edge, her posture languid though her eyes tracked the other’s every gesture. She looked up as Mrs Mow Fung posed a question, articulating each word slowly in Chinese, and the answer came in an equally measured tone.

Mrs Mow Fung’s sleeves made a faint, dry whisper as she moved and a moment later she tapped the yarrow stalks lightly on the square of silk. The woman said something inaudible, and Mrs Mow Fung gave a soft laugh in reply.

“Yes, they are called ai yao, and that lovely perfume lingers on them for a long time. But we should be quiet now and think only about what troubles you.”

Forster resisted an urge to clear his throat. He reached for the small teapot on the cane table and poured some tea into one of the two small, handleless Chinese cups Mow Fung had set down. He was sure the splash had cracked the silence, but neither woman looked up.

Forster closed his eyes. He flinched at the first sip of tea, then smacked his tongue lightly against his palate before taking another. It was a tad bitter, with a taste of mushrooms and … damp soil … that caught him off guard; but after he swallowed, a subtle aftertaste emerged: warm, sweet, and unexpectedly wholesome. He lifted the cup to his nose and inhaled its strange aroma.

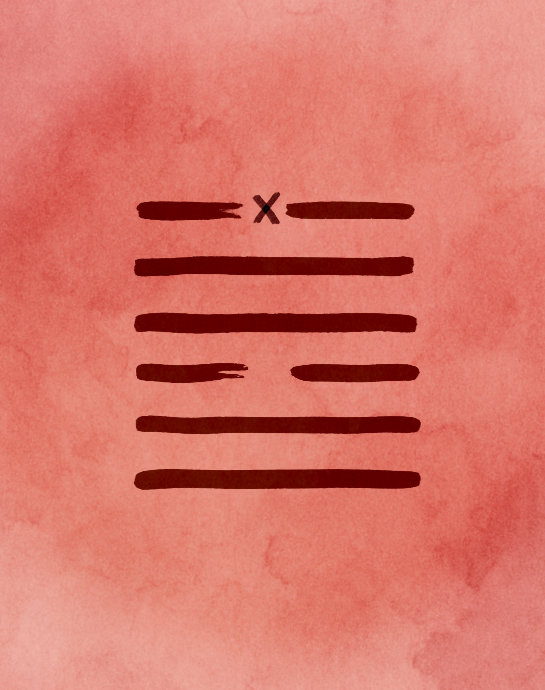

Across the room, Mrs Mow Fung spread the stalks slightly between her hands, then divided them into two uneven bundles, with practiced ease. From the right-hand pile she drew out a single stalk and placed it aside, distinctly articulating the word “Heaven.” The remaining stalks she counted in groups of four, sliding them gently between her fingers until three remained. These she laid to one side, and gathered the bundles again. The motion was repeated. Divide, draw, count, set aside – three times in all.

Forster listened to the rhythm: a rustling of sleeve, a concentrated breath, a feminine murmur. A pause. “Yang,” said Mrs Mow Fung. The younger woman took up the brush and marked a single line on the red paper – one clean, black stroke. Mrs Mow Fung took up a new bundle, and again the process unfolded: division, removal, counting. At the end of the cycle, she cupped the remainder in her palm and said, once again, “Yang.” Another mark was made – two strokes now, neat and parallel.

“It is excellent quality Pu-erh tea.”

Forster opened his eyes. The proprietor had materialised across the table. “It is,” Mow Fung added, “imported from the city of Pu’er in Yunnan province, the only place in the world it is cultivated.”

Clearly on an intuitive impulse, having judged something favourable in his guest’s manner, he paused and continued:

“‘Pu-erh’ is an important name in my life,” he said, “but not because of the tea. In my tradition, it’s also the name of a semi-immortal – a Perfected being, a sort of spiritual ancestress.

“When I was an infant, there was a ritual – a dedication, not unlike a christening – where she was named as my guardian. When I grew a little older, I was told she had been my mother in earlier lives. Her task, I learned, was to help me return to my original true self.”

Forster blinked, having anticipated nothing quite so personal, nor so metaphysical. Each looked quietly at the other as the words echoed away, infusing the atmosphere of the tearoom.

“Unfortunately, I could never learn to do that.” Mow Fung chuckled as he reached for the teapot and poured again, the dark stream sliding softly into each cup. The deep, earthy perfume rose. “If you are not used to it,” he said, “it can taste a little like mushrooms and dirt.”

“It’s not too bad,” Forster said. “Even to a milk-and-two-sugar man like myself. You’re uncannily right about the flavour. Must’ve read my mind.”

“Much easier to read the face,” said Mow Fung. “Tongue-sounds too – most revealing.”

Unsettled, Forster reverted to a tone of workaday officialdom, which rang oddly in his own ears amid the intoxicating bouquet of the Pu-erh tea.

The female voice came from the far corner, and Forster glanced across to see the young woman holding the calligraphy brush upright in her left hand, poised to paint a mark.

“Shame about that article – you and the doctor, after the post-mortem,” Forster said. “One of the constables tried to chase off that blasted reporter hanging about, but unfortunately not firmly enough.”

If Mow Fung noticed the tone at all, he betrayed it only in the steady, crystal gaze he cast into Forster’s eyes before reverting to his humble mien. The atmosphere was once more in balance, as the women’s voices drifted and the yarrow stalks whispered on the silk.

“Ah,” he smiled. “Newspaper. Sometimes the young reporter sees what he wants to see. Wants to make the reader of the newspaper feel superior to a lowly ‘Chinaman’ like myself. Always so. Very natural.

“In this case, Doctor Bennett needed to wash his hands, but Mow Fung could not allow the dead man’s spirit to adhere to utensils like a bowl or towel – not only for the purity of the space, but for the spirit’s own journey. He should not get stuck to more things here, but instead, progress through the proper stages into the beyond. For this dead man, such matters are especially important, because he is disconnected from his head. It is said by some that a person should be intact, or they will never escape from this world.

“So, leaning back, not to get splashed, I pour water from the trough over the doctor’s hands to wash them, with the water running into the earth, just as in our ritual cleansing. Doctor Bennett offers me the soap, but for obvious reasons, I refuse to take it back. And what do we find? Articles not only in Hamilton Spectator but as far away as Adelaide Observer. That ‘Heathen Chinee’ headline … Like all Chinese, superstitious, afraid of death, too ignorant to take the soap! Poor Mow Fung! Ha!”

Across the room, Mow Fung’s wife made two quiet raps on the table, freezing mid-motion as she replaced the stalks into their lacquered box.

“So sorry, my dear,” said the husband with a chuckle. “Getting a little excited. Since you’re finished, would you keep Detective Forster company while I fetch something I want to show him?”

The younger woman’s gaze flicked up – not startled, but suddenly still, her face passive for an instant.

“Detective,” she said, “I see.” She wiped the brush clean and pressed it gently into its groove beside the inkstone.

Forster, already halfway into a polite nod, faltered slightly.

“Would you care to join us?” said Mrs Mow Fung, smoothing over the pause.

“Only if I’m not interrupting,” Forster replied.

“We were done,” said the younger woman, her tone cool now. “All the lines are drawn.”

“Please – call me Anna, my English name,” said Mrs Mow Fung graciously. She motioned to the seat beside her. “This is my dear friend Lili.”

The young woman’s gaze slid from Anna to Forster and back again, and she offered a minimal nod.

“Excuse me,” she said to her reflection in the window, languidly adjusting her sleeve. A fine silver bracelet caught the light. “Teahouse rituals are deeply exhausting.” The trace of an American accent barely surfaced.

“You have been playing an intriguing game,” Forster said. He was looking at Anna when he spoke, but he caught a barely perceptible shrinking in Lili, like a bracing, or a folding inward.

“It is not quite a game,” Anna said gently, “but more of a window into ourselves. It can speak to you, if you listen.”

Lili regained her composure just as if it had never left. She tapped the red paper with the six parallel lines she had drawn. “It says someone in the room asks too many questions.”

“This picture is called a gua,” said Anna, ignoring Lili as she might an impertinent child. “You see it is made up of two parts, upper and lower; here they are both the same, a picture of a lake: two Yangs with one Yin – broken line – on top. That is a most desirable gua: one lake perfectly reflecting another lake; two lakes side by side, filled with water, sharing it all with each other. Creative is balanced by receptive. The inside and outside are as one, without any separation. It is a state of joy, or harmony, or even delight. Profoundly satisfying.”

Lili sipped her tea. “I’ve heard good things about joy,” she said dryly. “It’s on my list.”

Anna continued. “There is always a risk with joy: it must be correct. False, incorrect joy, will never last long but will disappear; having lost it, you will be worse off than before.”

“How poetic,” Lili said. “And how typical! A pair of lakes gazing longingly at each other, just before one of them evaporates.”

“Exactly,” said Anna, implacable. “The top Yin line, broken, is changing to Yang, unbroken – that’s why I asked you to mark it with an x. It’s the culmination of delight, but also its overturning. When we cling too tightly to pleasure, we lose ourselves. Everything changes and then comes the sorrow. That’s the nature of joy when it runs too far.”

She glanced down again. “Now look – only one Yin is left, and it’s climbing up through the strong Yang lines. This gua becomes a new one: Treading. Heaven above the lake. Like walking on a tiger’s tail – it may not bite, but you must tread carefully. Especially if that remaining, soft Yin is misused. Squint and miss the path; limp and the tiger turns and bites.”

Then, more softly: “But that one Yin – it’s also the key. It must remain open, yielding. That is not weakness. It’s the only way forward when the forces around you are strong. The gua speaks to your moment. It shows where you stand – and how to tread the path with clarity and grace.”

Forster ran his finger lightly around the rim of his teacup. “Well, I suppose if you stare at a thing long enough… Some say the mind produces answers of its own, even when we think we’re getting them from elsewhere. From cards, or symbols, or whatever’s at hand.” He lifted the cup to his lips. “Doesn’t necessarily mean they’re any less true.” Climbing up, Forster repeated to himself, smiling – or floating, maybe; the fact gently floating up of its own volition.

“Here is what I wanted to show you, Detective!” Mow Fung suddenly manifested himself in his irrepressible mode. He drew up an extra seat and slipped in between Forster and Lili, placing a small scrapbook on the table. “You will see how we are growing more famous and may soon catch up with even you, although we have not arrested even a single criminal.”

The scrapbook was open to a page with the “Heathen Chinee” clipping. Mow Fung laughed delightedly and tapped his finger on the next column, its headline set in bold capitals: “A Chinese Lady at Ararat.”

“Ah, this one,” he said. “Another of our local triumphs. You see – our old store on the Mullock Bank in Ararat and a banquet said to honour the arrival of a real Celestial lady from the Flowery Land.” He glanced at Anna with a boyish grin. “My wife’s debut on the goldfields. She was the marvel of the district.” He shook his head. “Eighteen years. How time flies. Tempus fugit … He frowned and glanced up, searching a different part of his brain: “Sed fugit interea, fugit …”

“Fugit irreparabile tempus,” said Lili, a singsong lilt in her voice, faintly amused by her own erudition. Mow Fung paused to look at her.

Forster quoted the Virgil: “But meanwhile it flees … time flees irretrievably.”

Mow Fung turned the book slightly so that Forster and the others could see the old clipping, the type still declaiming its truths after all these years. “The reporter wrote that half the township came to peer through the doorway. Then he says, ‘curiosity turned to drink, drink to uproar, and soon every man in the place was fighting – Europeans with their fists, Chinese with bamboo sticks: free fight and no favours.’ He casts me as ringmaster, conducting us Celestials in one-sided combat; and somehow we emerge the fools. while the drunken ruffians are likable country larrikins at heart.”

He laughed softly, without mirth. “As I recall, there was supper, some singing, too much beer, and one fool who threw a weight from the counter and smashed two jars. The police were fetched; the magistrate dismissed the case. But the paper had its say: a lady from the ‘Flowery Land,’ a ‘Celestial’ riot in her honour, and another good story for breakfast.”

Anna’s face barely shifted, but her minimal shrug suggested it took more than colonial attitudes to worry her.

Mow Fung smoothed the edge of the clipping with a fingertip, but it curled back again. “I keep these to remind myself that in print, the story that pleases is the one that endures. I have found joy in this peaceful settlement far away from the violence and strife I left behind in China.”

Forster shifted in his seat, unsure of what had unsettled him. Lili’s eyes lingered on the yellowing paper, musing, “And here I thought I was the exotic guest.”

Their host turned another page. “And here – something happier.” The headline, neatly set in small type, read: “Baptism of a Celestial Infant.”

“That was our first child,” he said. “The paper noted it as the first christening of a Chinese baby in the colony. It says the church was well attended, and that our boy bore himself with ‘admirable composure throughout the ceremony.’” He smiled faintly. “No one meant any harm. It was all quite kindly done – a curiosity for the readers, nothing more.”

His hand rested lightly on the page. “I remember the minister’s face: the awe with which he regarded a new life; and the townspeople, craning for a better view of the novelty. We thought of it as a gesture of friendship, a courtesy between faiths.”

He closed the book. “So – a happy clipping to end on.”

Anna’s eyes softened; Forster gave a small, respectful nod. Lili’s reflection was faint in the window. Now so close, Forster was struck by the quivering delicacy of her beauty – as though each passing second revealed a new facet, trembling and shifting. It reminded him of a tightrope walker: balanced, poised, never quite at rest. There was a fragility to her. Her black hair gleamed and her eyes glistened in the filtered light. A gleam set gently against stillness – that was the essence of her allure. There were traces of Chinese ancestry in her eyes, but something mutable in her features, as though they might shift to match any gaze that sought to define her. Depending on the light, the company, or the hour, she might seem unmistakably Chinese or equally European. A chameleon beauty: composed, ultimately unreadable. She brushed a hand lightly through her hair. A scar traced the line of her jaw.

“Shall I prepare some more tea?” she said, already rising.

From the draft novel Stawell Bardo © Michael Guest 2025