A bit of a coincidence, more names. And Cobb even explains their origins in detail. How do we respond to and interpret them? Now we hear of Irene and Wolfgang. In English, we pronounce Irene as in “serene”, with an emphasis on the second syllable. In German, it sounds quite different, despite emphasis on the same syllable. The letter “e” is pronounced as “eh”, in addition to a bounce on the second “eh”, making the same lovely name sound much more harsh. Not instantly a beguiling Irish maiden, but perhaps a bit of a standoffish Valkyrie?

It’s perhaps little wonder that the only German song about an Irene is “Leb Wohl, Irene” (Goodbye, Irene), the Nazi German song of the German flak unit drivers.

Or should I have not mentioned the war, after the BBC tried to ban the Fawlty Towers episode “The Germans” this year? (See “Fawlty Towers ‘Don’t Mention the War’ Episode Removed from UKTV” Guardian, 12 Jun, 2020.)

The German language is preferred by almost all lion and big cat tamers. Because these predators will more likely listen to you if you yell at them in German. The language even changes the way names are interpreted by us. Wolfgang sounds more foreboding in English, by contrast. The wolf and a sinister sounding gang? Which in German means only something like “gait” or “passage”. Goethe’s middle name, but still a popular one, even today. Mozart’s first, shortened to a cute little “Wolfie” in Amadeus, as his wife Constance is being chased by him around a table.

On the subject of playing with names, will the evil Dunwolf finally be done in by a wolf? Cobb gives him the name “Sir Pascal Dunwolf”. Because that might sound sinister the first time you hear it? Could it be the first name Pascal that causes this? Not that I had anything against Blaise Pascal, although I abhorred having to calculate hectopascals. An instant villain?

Or is it just me? Knights, in the many kingdoms, duchies and principalities of what later became Germany, were, in German, not given a title denoting knighthood, like “Sir”. They were of course noblemen, usually a von or a van something-or-other, but the fact that they might have been knights was bestowed by being a member of the “Deutscher Ritter Orden“, the German (or Teutonic) Order of Knights, with no extra title added to the name.

CHAPTER 4

A BRIEF, SWEET DREAM

Towards the middle of the forenoon of the day following that on which the funeral at the castle had taken place, Irene Oberwald sat at the door of her father’s cot with a magnificent St. Bernard dog lying at her feet. Her distaff was before her and she was warbling a pretty little love-song as she spun her flaxen thread. Her father had gone down to the village in quest of medicine for his strange patient, and she had been left in charge.

Thus she sat, busily spinning, and thus she sang, when a warning growl from her guardian gave token that something was approaching — something that might be dangerous, or Lion would not have uttered that particular note of alarm. She quickly set her distaff aside and arose to her feet, and as she did so the dog growled more deeply than before, and assumed an attitude of defiance. In another moment she heard the sound of a footfall behind her, and on turning she beheld the cause of her guardian’s disquiet. She had been looking in the direction of the village, supposing that any visitor would come that way, but the intruder had come from the opposite point. This is what she saw as she stood with her hand upon the head of the dog to hold him at her side; but her precaution was needless. The intelligent brute, having given one fair look into the new face, gave token of entire satisfaction.

A man in a garb almost a duplicate of the garb worn by the man who now lay so sorely wounded near at hand; but a man very, very, very different. The girl’s first thought on seeing him was: “How like these robbers are; and what handsome men!” — for it was very evident at sight that he now before her was comrade with the other. Another thing passed through her mind, and was silently spoken: “How can men leading such a life wear such honest, truthful faces?”

For the man before her she thought the handsomest, and the noblest, and the most truly loveable, she had ever seen. He was not more than five-and-twenty years of age, with a face the very picture of manly beauty and elegance. A mass of bright golden curls swept away from a full, open brow; his eyes, large and lustrous, were of a blue like the sapphire; his only beard being a prettily waving moustache upon the upper lip. The collar of his frock was open low in front, exposing a neck and the upper part of a bosom as fair as alabaster; and when he smiled his teeth gleamed like pearls. His cap, or bonnet, of purple velvet, bearing a rich, white ostrich feather, he held in his hand. He wore a sword of goodly size, with a hilt of gold, and a brace of pistols, also mounted with gold, were in his girdle. He was of medium height; of perfect form; compact and powerful.

“I think I have found the dwelling of Martin Oberwald,” he said, in tones that sounded wonderfully melodious in the ears of the hunter’s daughter. Irene trembled, for her first thought was of the wounded man to whom they had given shelter; but her fear was only for the moment. “Surely,” she said to herself, “this man cannot be a traitor nor an enemy.” He marked her hesitation, and presently added, with a smile that banished the maiden’s last scruple:

“Do not fear, fair lady. I would be the last to bring trouble upon your father’s abode. I will be frank with you, and I ask you to trust me. I am in search of a friend, and I think he has found blessed shelter beneath your roof. Am I wrong?”

“If you would tell me the name of your friend, good sir—or,” she added, after a momentary pause, “perhaps l ought not to ask it.” Another pause, and she went on, with an answering smile—the smile came of its own accord:

“I will be as frank as you have promised to be, fair sir. A stranger, sorely wounded, is at this moment beneath our roof. His name I do not know.”

“Your father doubtless knows it.”

“I think so; I am not sure.”

“Let us call him — What shall it be?” the stranger said, with a smile that had a tinge of merriment in it. “What name should you give him?”

“I would not dare to name him, sir.”

“But, of course, you have given him a name in your thoughts. Will you speak it? No harm can come from that, I give you my solemn promise.”

That was enough. The last remnant of doubt was swept away, and she resolved that she would trust the man fully.

“I would call him,” she said, almost in a whisper, — “THORBRAND.”

“Bless you for an angel of mercy and goodness!” the stranger exclaimed, from the fulness of his heart. “In that answer I read more than you think; I can see that a kind Providence must have led my poor friend in this direction. But tell me — how fares he? Was he very severely wounded?”

“He was most terribly wounded. Had we not found him as we did he could not have lived many minutes. His life was running swiftly away from a deep wound in his bosom.”

“You and your father found him?”

“Nay, sir, my companion was Electra von Deckendorf.”

“Who?” quickly demanded the stranger, with a palpable start as the name struck his ear.

“Electra, daughter of the noble Baroness von Deckendorf.”

“She it was?”

“Yes, sir; and she it was who saved his life. I should not have known what to do; but she had studied chirurgery. She knew exactly what to do. O!” with a little cry of terror in memory of the scene — “how she had the courage to plunge her finger into the deep wound! I could not have done it if the wound had been on my dog.”

“Bless the dear lady! We must find some fitting recompense for her most noble deed.”

“Ah, sir!” cried Irene, without stopping to think, “if you could save her from a fate that threatens to make wreck and ruin of her joy forever, you would do a blessed thing indeed.”

“Ha! What now! Who has dared? — But perhaps you will allow me to take a seat.”

“Pardon me, good sir; I did not think,” and she pointed to the seat in which we first saw the young lady of the castle. As he sat down he said, with a smile that was captivating:

“Now, fair lady, if you will add to your kindness by telling me your name I shall be grateful.”

“That is hardly fair, sir. You know already who I am, while of yourself I know absolutely nothing.”

The stranger laughed a light, merry laugh, and presently said:

“Since you have my dearest friend a prisoner beneath your roof, I certainly should not fear to speak my name in your hearing but I would prefer that you should keep it to yourself, only, of course, telling your father, in case I do not see him.”

“You may trust me, sir.”

“I know it, sweet lady. Those lips of yours could no more conceal a lying tongue than Heaven itself could prove false. You may call me WOLFGANG. “

“I am called Irene,” was the maiden’s response, scarcely above a whisper.

Something in her bosom — it seemed near her heart — oppressed her. She knew not what it was — she did not try to think; she only knew that never before had such a feeling been hers. She had just bent her head, with her eyes cast upon the ground, when the tones of her companion, more musical, if possible, than before, caused her to look up.

“Do you know the signification of that name — IRENE?”

“No, sir,” she replied, wondering.

“Shall I tell you?”

“Certainly.”

“Then, listen.” He looked directly into her eyes with an expression upon his eloquent features that thrilled her through and through. ”The ancient heathens had a deity whom they worshipped as the personification of the Spirit of Peace. The Greeks called her Eirene. After the Romans had adopted Christianity, they gave that name to certain women whom they wished particularly to honor, calling it, as it has. been called ever since, IRENE. Several of the Greek empresses bore the name, and it was never given to one of humble station except for the purpose of rendering especial honor to her. So, do you see, you should be proud that your parents conferred it upon you.”

“And now, Meinherr,” said the hunter’s daughter, after a little silence, ”can you tell me if your name has a signification?”

“Ah! that is cruel; but I forgive you. Yes, the name has a signification, and you can read it in the name itself: WOLF-GANG — the Wolf’s course, the Wolf’s track; but perhaps it might be more properly given as the Wolf’s progress. Let me hope that the name will not frighten you.”

“Indeed, no, sir; for I cannot believe that you could in any way resemble the wolf.”

“And now,” said the visitor, seeing that the maiden was beginning to be troubled, “we were speaking of the young lady of the castle — Electra. What is the character of the danger that threatens her?”

As she seemed to hesitate, he presently added:

“I wish you would trust me, not only for the lady’s own sake, but for the sake of the man whom she so gallantly served. You may not know — I doubt if you have any idea — of that man’s power. And perhaps I can render her aid. Strange things sometimes happen in this world of ours.”

Irene caught at the promise of help eagerly. Her heart had been aching ever since she had seen the dark, sinister face of Sir Pascal Dunwolf at the castle; and now had come a beam of hope. If she could in any way secure help to her beloved sister she had no right to neglect the opportunity. She bent her head for a brief; space in thought, and finally looked up and spoke. Her eyes were clear and steady in their beaming eloquence, and she looked straight into her listener’s face as she told him the story.

She told of Electra’s childhood; of Ernest von Linden, and his adoption by the baron; of the love and the betrothment of the children; how they had gone on loving more and more, to the present time. She told of Sir Arthur; of his sickness and death; and then of the unfortunate whim of the grand duke; the suffering which it had occasioned; and finally, of the coming of Sir Pascal Dunwolf, just as the mortal remains of Sir Arthur von Morin had been laid at rest in the family vault.

Irene had spoken more eloquently than she knew. Had her own heart been the scene of the suffering of which she told she could not have given to the story more feeling. Wolfgang had listened in rapt silence, his eyes fixed upon the face of the speaker as though by a spell. When she had concluded, he spoke, without premeditation, the words seeming to issue from his lips of their own volition, as though he had been dreaming, and spoke before being wholly awake.

“Ah!” he said, a shadow resting upon his fresh, handsome face, “it is plainly to be seen that you know what true love is.”

“Yes,” she responded, with simple honesty, her thoughts given so entirely to the story she had been telling that she did not catch the deeper significance of his words; “yes; I love my good father; and I could not love Electra more if she were my own sister.”

“And another! Is there not another, at the sound of whose voice your pulses quicken, and your heart leaps with a wondrous emotion?”

There was something in the man’s look — in his tone and bearing—that would not let her take offence. There was a slight tremor, quickly overcome; then a beaming smile, as she answered:

“You mistake, sir. The emotion of which you speak was never mine.”

It was strange how quickly the cloud passed away from Wolfgang’s face, and what a glorious light came into his blue eyes. Really, it seemed a transfiguration.

“I beg your pardon,” he said. “And I ought perhaps to beg your pardon for having kept you so long in conversation, though I am free to confess that I have enjoyed it. I thank you for having trusted me in the matter of the young lady of Deckendorf. I think I must have an eye upon the dark-visaged knight.”

“O, Sir! Do you think you can help the dear lady?”

“I can certainly try.”

“But if he has the authority of the grand duke to uphold him?”

“The grand duke must be seen. Let the true lover go to Baden-Baden, where I believe Leopold at present has his headquarters.”

“He is going, sir. He would have gone ere this had it not been for the death and funeral of the aged knight — Sir Arthur.”

“Very well. Let Ernest von Linden look to the grand duke, and I will look to Sir Pascal. If I am not much mistaken, there is an unsettled account between us. Rest you easy, sweet lady, for I think I may promise you that your friend shall be saved from the fate she so much dreads. And now, if you do not forbid, and if you will kindly show me the way, I will go and see my friend and frater, Thorbrand.”

“One word, good sir!” said Irene, with marked eagerness, as her visitor rose to his feet.” Because I gave you that name so readily, you will not think I would have carelessly exposed it.”

“Bless you!” he cried with a kindling glance. “I thought you were wondrously careful in your keeping of the secret. No, no; I understand the matter much better than you can explain. You trusted me because you believed me trustworthy — following your own good judgment; as I will do always.”

“The girl thanked him with a smiling look, and then led the way to the rear of the cot; and when they had come in sight of the door of the room in which the wounded man lay, she pointed it out and bade him enter. He went to the door and gently opened it and passed in. He closed it without noise, and in a moment more she heard a glad exclamation in the deep tones of the Schwarzwald chieftain followed by the musical notes of the voice of the visitor.

Once more in her seat at the outer door, Irene drew up her distaff, and took a mass of the flossy flax in her hand, but she did not resume her spinning. An emotion new and strange was in her heart — a feeling never before experienced — a something that reached to every fibre of her being, thrilling her through and through. For a little time she sat as in a trance, without thought of any kind, her eyes half closed, her hands pressed on her bosom. And by and by she murmured, like one dreaming aloud:

“Surely he must be a good man. He cannot be a robber. If he is — if such a thing were possible — there must, be some wonderful story in his life; some upheaval, wreck, ruin; some terrible treachery of professing friends, that drove him to the free life of the mountains. I wish I dared to ask him. Whatever he told me I should certainly believe.”

She laid aside her distaff and arose, and began to pace slowly to and fro before the door. She was asking herself a solemn question: Had anything akin to love been awakened in her bosom towards the youthful mountaineer? Surely there was in her heart a feeling never known before. But — pshaw! how wild and foolish it was to speculate upon the subject! She would probably never see the man again, and yet, as she told herself so, a sense of desolation came upon her; a bright star seemed suddenly blotched out from the heaven of her life.

She was thus slowly walking and deeply meditating, when a glad cry from her dog recalled her to herself, and on turning, she beheld her father close upon her.

“Papa! O! I am glad you have come. We have had a visitor. — There! There! Be not alarmed. The wounded man, I am very sure, was anxiously expecting him.”

“Ha! — is it — Did he give you his name?”

“Yes.”

“Was it — Wolfgang?”

“Yes, papa!” she cried, seizing him by the wrist us she spoke. “He told me his name without fear. Do you know him?”

“No. I never saw him.”

The bright countenance fell in a moment, but presently it lighted up.

“You know who he is, dear papa. You know something about him.”

“Child, why are you so anxious! What can the man be to you? Look ye: Has he been talking tender nonsense to you?”

“O, papa!”

“Pooh! I was but jesting, my darling. And, moreover, I do not think Wolfgang — if it is really he —is at all such a man.

”Indeed, he is not. I never heard a man talk so wisely and so well.”

“Oho! Then you have had a good bit of a chat, eh? And what sort of a man is he? Describe him to me, for be assured I have a deep interest in knowing all about him.”

Without hesitation — from the fulness of an overflowing heart — the girl honestly and sincerely spoke:

“He is the handsomest man I ever saw; and one of the grandest looking. I know he is brave; and I know he is true. A face like his could not belong to a man in whom there was a single grain of falsehood or deceit. And then, he is educated. He talked to me of things that I never knew before — talked like one whose understanding was deep and profound. If he is a robber — but I do not like to think of him as such. At heart I know he is not evil.”

“An elderly man, I take it.”

“Elderly! What are you thinking of? Why, he is not much older than — I won’t say that. But he is very young, not more than three or four-and-twenty.”

The stout hunter gazed upon his daughter curiously. The smile which had at first broken over his kindly face faded away, and a look of deep concern took its place. After a little time he laid his hand tenderly upon the sunny head, and gently said:

“My blessed child, beware of that heart of yours! I plainly see that this man has made a deep impression upon you. I simply ask you to keep a strong hand upon your affections, and especially upon your fancy. I think Wolfgang is an honest man, and true; but be sure, he will never seek a mate in these mountains.”

“Oh! papa!”

“Tush! That is all. Now go about your work, and I will go in and see our visitor. I suppose he is still with — his chief.”

“Yes. He is in the —”

The hunter did not wait for her to finish the sentence, but turned away at once towards the rear of the cot.

Irene watched him until he had disappeared from her sight, and then she sank upon a seat, buried her face in her hands, and burst into tears. For a time her heart seemed well nigh to breaking; but at length she started up, and dashed away her tears, and told herself that she was a fool. And the more she thought of it the more foolish the whole thing appeared. It had been a brief, wild dream, with her whole heart involved; but she had happily awakened, and she told herself that that was the end.

Then she went to the little well-room and laved her face in the crystal water of the spring, after which she returned to her distaff, and set resolutely about her spinning; and as she watched the tiny thread lengthening and gleaming in the slanting sunbeams, she thought of the handsome stranger, and repeated the sweet words he had spoken.

So she spun, and so she thought, resolving all the while that she would think no more.

Notes

- Leb Wohl, Irene: See Addendum below for English translation of lyrics.

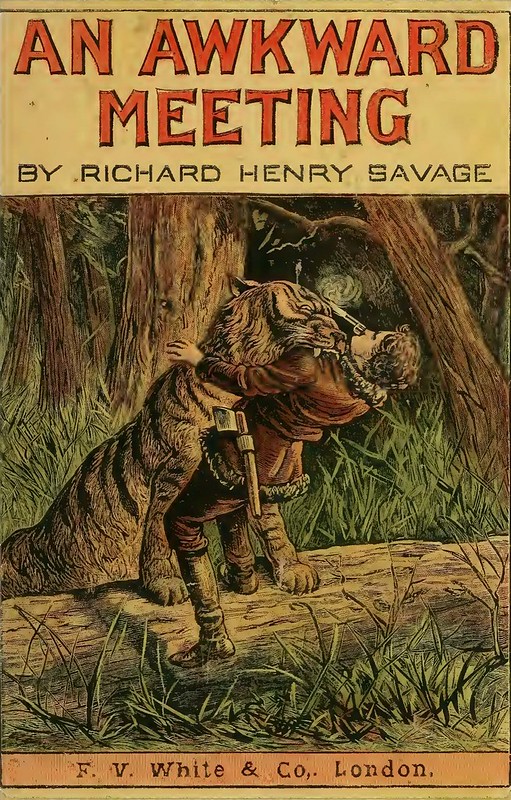

- Portrait of Mr. Van Amburgh: Isaac van Amburgh (1808-1865). Dutch-American lion tamer. See also, “Isaac van Amburgh and his Animals,” Royal Collection Trust, UK.

- distaff: A stick or spindle on to which wool or flax is wound for spinning. (Lexico.com)

- frater: Comrade

- kindling glance: Not so much the sense of kind as kindling something. See, for example, “Terpsichore” in Poems by Oliver Wendell Holmes: “And there is mischief in thy kindling glance” (in Making of America, U of Michigan Library).

- laved: Washed

Addendum

English translation of lyrics of “Leb Wohl, Irene” (Goodbye, Irene) (Das Flak Lied) (Source: “Axis History” and Google Translate.)

1. We go back and forth we drive all over the place. Throughout the country we are known by every girl with taste as a driver of the flak. Chorus: Farewell, Irene! Love me, Sophie! Be good, Marlene! Are you staying true to me, Marie? You are so lovely, so beautiful, so cheerful, but unfortunately I have to go on again. Farewell, Irene! Love me, Sophie! Be good, Marlene! Are you staying true to me, Marie? I will always love you. I love you new in every new place! 2. We go back and forth we drive all over the place. Somehow sits A battery in one spot in the thick dirt, there we take them away. Chorus 3. We go back and forth we drive all over the place. And it turns out the war is over, let's go home on the last day the flak with sack and pack. Chorus