The nexus of the Louise Minturn and Harry Larchmont characters is reached: their shared connection to Fernando Montez. This is all as the reader might expect from knowledge of Louise’s letters. However, Gunter wants to create a selective perspective of prior events involving Harry that the reader may later share with Louise. Not content with the attributes and qualities he has endowed his characters, Gunter seeks to intrude on the imaginative mental stream of the reader to frame and accentuate the action through his narrator and by other means.

In Harry’s repartee with Louise in the last chapter, he revealed more of the ‘player’ he is reputed to be. At the close of the chapter, his impetuous act in separating Louise from the presence of Wernig weighs heavy on him, though his thoughts dwell, not on the beautiful Louise, but on his next steps to retrieve his brother’s fortune.

Though there is no desire to disrupt the reader experience, in order to explore Gunter’s narrative strategy some notes on the content of the chapter ahead is required.

Harry is on deck smoking cigars again one night, still, one would think, intoxicated with the vision of beauty that was Louise as she left him. Yet it appears in his meditations he has become resolute in a course of action of which some might be critical, perhaps deem dishonorable. Though having access to Harry’s more precise thoughts, Gunter declines to reveal them, and so leaves the reader guessing. Little mysteries add realism to a modern novel as they are part of everyday life, but this has the dramatic touch of deliberate obfuscation.

At one juncture while informing Louise of the plight of his Francophile brother, Harry bemoans the lack of teaching of American culture in schools. He mentions the nascent sports of baseball and football (we know what becomes of them). But beyond this, one might ask; to what American culture is he referring? The U.S. may boast a number of technical and industrial development achievements, and there are substantial literary best sellers throughout the nineteenth century. Novels such as The Last of the Mohicans by James Fenimore Cooper, Uncle Toms Cabin by abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe, Moby Dick by Herman Melville and the very popular Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain which sold in the hundreds of thousands in the U.S. and overseas. And for generations without radio or film or television, and limited access to the theatre or books, entertainment was the circus coming to town. New railways meant the circus could reach many more thousands of people throughout America, and steamships meant many more overseas; Europe and even as far as Australia (Worrall). America’s chief cultural exports of the time were Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and P.T. Barnum’s Greatest Show on Earth billed as a circus, museum and menagerie (Watkins).

This isn’t the first time via Harry this apparent manifestation of inverse cultural cringe (Phillips) has presented with a skew-whiff reasoning. Describing his brother, he equates U.S. disaffiliation with loss of manhood. Gunter is something of a showman himself, and providing entertainment and being sensational is his game. Sensational, to his contemporary audience, is a nineteen-year-old young woman travelling alone without a companion on a steamship to a foreign country, but that is not sufficient. The author wants to provoke emotion-based opinions in his readers where none may have existed. The well-to-do are an easy target for prejudice, and patriotic transgression adds a certain righteousness.

Louise has been portrayed as independent, beautiful, at times haughty with strong sense of personal worth, smart, accomplished and not afraid to speak her mind. Shortly after the letters appear, the reader may note an abrupt temporary change in dialogue attributions for our female character. Where before it was ‘Louise’, ‘Miss Minturn’ even ‘the young lady’, now it is ‘the girl’. An apparent attempt through subliminal manipulation to present Louise in an inferior position. So too is the narrator’s suggestion of a tone of proprietorship in Harry’s voice in respect of Louise’s morning agenda, which includes inspecting the letters.

Louise’s letters are the focus of the chapter, though Harry’s persistence seems a little uncharacteristic, which even Louise remarks upon. On a comment from Harry regarding activities post letter-reading, the narrator cannot resist an amused aside from insider knowledge of what is to come—part of egging the reader on.

Gunter, through his narrator, is the ringmaster of the various elements of the story that inhabit the reader’s imagination. In a previous intro we covered the paucity of entertainment available to the common man and woman, excluding a possible circus visit. Before the visual artistic forms of film and television, the novel was the chief direct access to the active mental plane of individuals—through their eyes. Reminders of the narrator’s aural presence as storyteller, of being read to by a third entity have the effect of distracting from the smooth ongoing visual transmission to imagination. There is a shift away from the self-created illusion of reality to acknowledging an amusing fictional entertainment. As the crescendo of the chapter becomes imminent, the narrator cannot resist a snide comment which raises jealousy over integrity as motivation, perhaps to dilute the colour of Louise’s final response, and perhaps also to secure for the author an avenue for later re-engagement.

And now ladies and gentlemen, without further ado, for your reading pleasure, if you will direct your attention to the centre of the page below. Furin Chime is proud to present, for the first time in a hundred and twenty-five years—the next chapter in the Baron Montez saga! Please enjoy the show!

CHAPTER 13

THE BUNDLE OF LETTERS

The next day Herr Wernig has become again effusively affectionate and thrusts his society upon Mr. Larchmont, though that young gentleman gives him but little chance, as he is again devoting himself to the second cabin passengers.

This time, he has dropped the society of the man Bastien Lefort for that of one of the second-cabin ladies.

This lady has a little child of about five. With paternal devotion Harry takes this tot up and carries it about, as he talks to the mother. This attention seems to win the lady’s heart. And he spends a good deal of the morning promenading by her side. By the time he returns to lunch in the first cabin, “his flirtation,” as they express it, has been pretty well discussed by the various ladies and gentlemen of the after part of the ship. Of course it comes to Miss Minturn’s pretty ears, and sets her wondering.

After an afternoon siesta—for the boat is now well in the tropics, and everybody is drifting with it into the languid manners of the torrid zone—Louise strolls on the deck for a little sea breeze, and chancing to meet the gentleman of her thoughts, puts her reflections into words.

This subject is easily led up to, as Mr. Larchmont even now has in his arms the little girl from the second cabin.

“Miss Louise,” he says, “this is a new friend of mine. This is pretty little Miss Minnie Winterburn, the daughter of a machinist on one of the Chagres dredgers. Her father has been out there almost since the opening of the railroad. He is by this time used to yellow fever.”

“And her mother?” suggests the young lady rather pointedly, for Harry’s speech has been made in a rambling, semi-embarrassed manner.

“Oh, her mother,” returns Mr. Larchmont, “is on board in the second cabin. She is much younger than her husband—third or fourth wife—that sort of thing, you understand. I have brought the little lady aft to get some oranges from the steward.” Which fact is apparent, as the child is playing with two of the bright yellow fruits. “If you will excuse me, I’ll return my little friend to maternal arms, and be with you in a minute. Let me make you comfortable on this camp stool.”

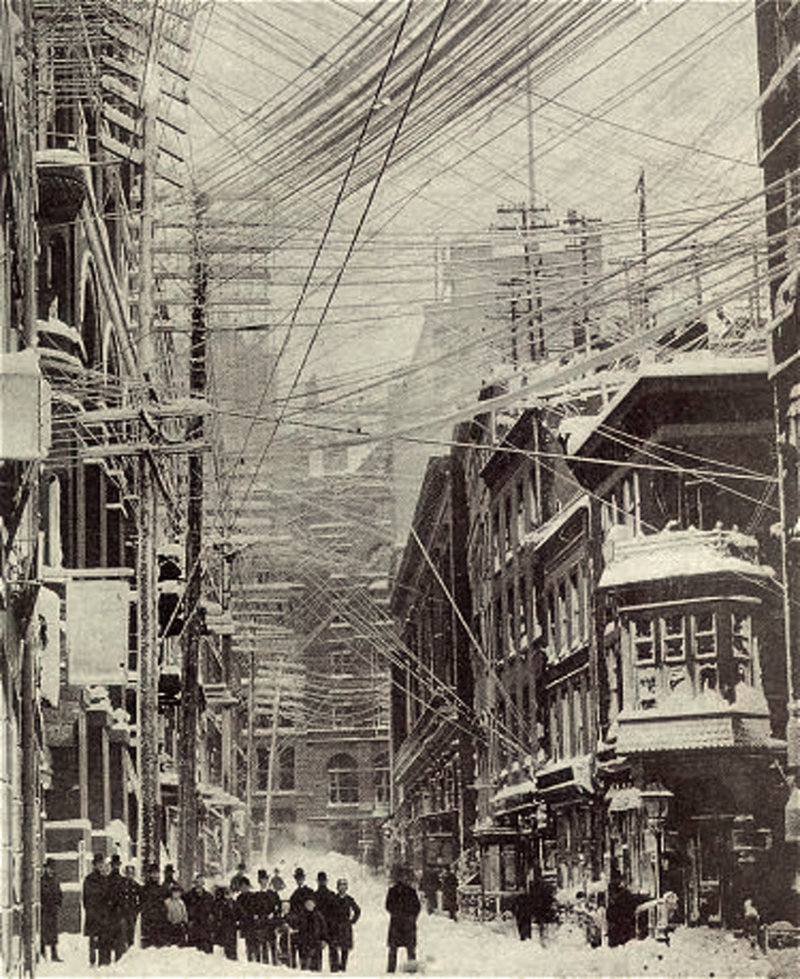

Arranging the seat for her, Harry strolls off with the little girl. As he walks away the young lady’s eyes carelessly follow him; suddenly they grow tender. She notices the careful way he carries the little tot, and it reminds her of how he had borne her through the snow and ice of that awful New York blizzard.

Apparently the emotion has not left her eyes when Larchmont returns to her; for he says, his eyes growing tender also: “Tonight we will have another musical evening?”

“Oh, I’m not going to sing for you this evening,” ejaculates the young lady lightly, for seats beside each other three times a day at the dining table, and the easy intercourse of shipboard life have made her feel quite en camarade with this young gentleman, save when thoughts of her diary bring confusion upon her.

“Why not?”

“Oh! Second cabin society in the daytime, second cabin romance at night.”

“Was there a first cabin romance last night?” asks the gentleman, turning embarrassing eyes upon her.

“No—of course not—I—I didn’t mean anything of the kind!” stammers Louise.

“Indeed! What did you mean?”

“I meant,” says the girl, steadying herself, “that you seem to prefer second cabin society during the daytime—why not enjoy it also in the evening?”

Whereupon he startles her by saying suddenly: “How a false position makes everything appear false! I presume, Miss Minturn, you imagine I enjoy the patois of Monsieur Bastien Lefort, and the good-hearted but homely remarks of the wife of the machinist—but I don’t!”

“Then why associate with them?”

“That for the present must be my secret! Miss Louise, we have been very good friends on shipboard. Don’t go to imagining—don’t go to putting two and two together—simply believe that I am just the same kind of an individual as I was five days ago.” Then he brings curious joy upon her, for he whispers impulsively, a peculiar light coming into his eyes: “No, not the same individual!” and gives the young lady’s tempting hand, that has been carelessly lying upon the arm of her steamer chair, a sudden though deferential squeeze; and with this, leaves her to astonished meditation.

She does not see him till dinner, which he eats with great attention to detail and dishes. But, though he says very little, every now and then he turns a glance upon her that destroys her appetite.

At dessert, this is noted by the captain, who in his affable sailor way, with loud voice suggests: “What’s the matter with your appetite, Miss Louise? Has the guitar playing of last night taken it away? Not a decent meal since yesterday.”

“Oh,” replies the young lady, “the weather is too hot for appetite!”

“But not for flirtations!” says the awful seadog. Then he turns a winking eye upon Larchmont, and chuckles: “Remember, Harry, kisses stop at the gang plank!”

“Not with me!” says the young man, determination in his face and significance in his tone: “If I made love to a girl on shipboard, I should make love to her—always: I’m no sailor-lover!” With this parting shot at the skipper he strolls from the table, and goes away to after dinner cigar.

“By Venus, we’ve a Romeo on board!” cries the captain. “Where’s the Juliet?” and turns remorseless eyes upon Miss Minturn.

Fortunately this little episode has not been noticed by any of her fellow passengers, nearly all of them having left the table before Mr. Larchmont.

A moment after, Louise follows the rest on deck, blushes on her cheeks, brightness in her eyes, elasticity in her step. She is thinking: “If he loved me, he would love—always. Did he mean that for—” Here wild hope stops sober thought; but after this there is a curious diffidence in her manner to Mr. Larchmont, though she does not avoid his companionship—in fact, from now on, he can have her society whenever he will, which is very often.

This evening he asks for more songs, and gets them, perhaps even more soulfully given than the evening before. So the night passes.

And the next day is another pleasant tropic one, that the two dream out together under the awnings, with bright sunshine overhead, and rippling waves, that each hour grow more blue, running beside them as the great ship draws near the Equator.

And there is a new something in both their eyes, for the girl has thrown away any defences that her short year’s struggle with the world of business may have put about her, and is simply a woman whom love is making more lovely; and the gentleman has forgotten the conservatism of his conservative class, and is becoming ardent as the sun that puts bronze upon their blushing faces.

So the second evening comes upon them, and the two are again together on the deck, and the strings of the girl’s guitar seem softer and her voice is lower.

Then the crowd on deck having melted away, their moonlight téte à téte, as the soft blue ripples of the Caribbean roll past them, grows confidential. Drawn out by the young man, Miss Minturn, gives him her past history, which interests him greatly, especially that portion referring to the disappearance of her mother’s parents on the Isthmus.

He suggests, “In Panama, perhaps you may learn their fate.”

“But that was so long ago,” says Louise.

“Nevertheless—supposing you look through your old letters. It won’t do any harm. Let me help you. It will give us a pleasant morning’s occupation,” goes on Harry, quite eagerly.

“Don’t you think you could be happy without the letters?” laughs Louise. Then she suddenly whispers: “Oh, they are putting out the lights!” and rises to go.

“Blow the lights!” answers Larchmont, who is out of his steamer chair, and somehow has got hold of Miss Louise’s pretty hand. “Promise the morning to me.”

“The whole morning?”

“Why are you so evasive? Promise—will you?”

“Yes, if you will stop squeezing my hand. You—you forget you have football fingers!” gasps Louise; for his fervid clasp upon her tender digits is making her writhe.

“Forgive me!”

“O-o-oh!”

He has suddenly kissed the hand, and the girl has flown away from him.

At the companionway she turns, hesitates, then waves adieu, making a picture that would cause any man’s heart to beat. The moonlight is full upon her, haloing her exquisite figure that is draped in a soft white fluttering robe that clings about it, and would make it ethereal, were not its round contours and charming curves of beauty, those of the very birth of graceful, glorious womanhood. One white hand is upraised, motioning to him; one little slippered foot is placed upon the combing of the hatchway. Her eyes in the moonlight seem like stars. Her lips appear to move as she glides down the companionway. Then the stars disappear, and Harry Larchmont thinks the moon has gone out also.

He sits there meditating, and after a little, his lips frame the words: “If I did, what would they say?” Then rising, he shakes himself like a Newfoundland dog that is throwing the water from him, tosses his head about, puts his hand through his curly hair, laughs softly, and says to himself: “Hanged if I care what anyone says!”

Curiously enough, he does not go to the cardroom this evening, for he paces the deck for some two hours more, meditating over three or four cigars that he smokes in a nervous, excitable, fidgety manner.

The next morning, however, as Miss Louise, a picture of dainty freshness, steps on the deck, he is apparently waiting for her. His looks are eager. There is perchance a tone of proprietorship in his voice as, after bidding her good morning, he says: “A turn or two for exercise first, then breakfast, and then the letters!”

“Oh, you are beginning business early today,” laughs the young lady, whose eyes seem very bright and happy.

“Yes. You see I want all your morning.”

“Then you will have to read very slowly,” suggests Miss Louise, “or the letters will not occupy you till lunch time.”

“After the letters are finished, there will doubtless be something else,” remarks the young man confidently; and in this prediction he is right, though he would stand aghast if he knew what he prophesied.

So the two go down to breakfast together, and make a merry meal of it, as the captain, occupied by some ship’s duty, is not there to embarrass them by seadog asides and jovial nautical jokes that bring indignant glances from the young man, and appealing blushes from the young lady.

They have finished their oranges when Mr. Larchmont says eagerly: “The letters!”

“They are too numerous for my pocket!” answers the girl.

“You have not read them?”

“Not for years. In fact, I’ve forgotten all there is in them, except their general tone; but I fished them out of my trunk last night.”

“Very well! Run to your cabin, and I’ll have steamer chairs in the coolest place on deck, where the skipper will be least likely to find us,” replies Harry; and the young lady, doing his bidding, shortly returns to find a cosy seat in the shadiest spot under the awnings, and Mr. Larchmont awaiting her.

“Ah, those are they!” he says, assisting her, with rather more attention than is absolutely necessary, to the steamer chair beside him, and gazing at a little packet of envelopes grown yellow by time, and tied together with a faded blue ribbon. “These look as if they might contain a good deal.”

“Yes,” replies the girl, “they contain a mother’s heart!”

Looking over these letters that cover a period of four years, they find that Louise is right. They have been carefully arranged in order. Most of them are simply descriptions of early life in California, and of Alice Ripley’s husband’s efforts for fortune and final success; but every line of them is freighted with a mother’s love.

The last four bear much more pointedly upon the subject that interests the young man and the young lady The first of these is a letter describing Alice Ripley and her husband’s arrival at San Francisco en route for New York, and mentioning that she encloses to her daughter a tintype taken of her by Mr. Edouart, the Californian daguerreotypist.

“You have the picture?” asks Mr. Larchmont.

“Yes,” says the girl. “I brought it with me, thinking you might like to look at it,” and shows him the same beautiful face, the same blue eyes and golden hair that had delighted the gaze of Señor Montez in faraway Toboga in 1856.

“It is rather like you,” suggests Harry, turning his eyes upon the pretty creature beside him.

“Only a family likeness, I think,” remarks the young lady.

“Of course not as beautiful!” asserts the gentleman.

“I wish I agreed with you,” laughs Louise. Then she suddenly changes her tone and says: “But we came here to discuss letters, not faces,” and devotes herself to the other epistles.

The second is a letter written by Alice Ripley from Acapulco, telling her child that sickness has come upon her; that she is hardly able to write; still, God willing, that she will live through the voyage to again kiss her daughter.

The third, in contradistinction to the others, is in masculine handwriting, dated April 1oth, 1856, and signed “George Merritt Ripley.”

“That is from my grandfather,”says Louise.

Looking over this letter, Larchmont remarks: “A bold hand and a noble spirit!” for it is a record of a father’s love for his only daughter, and it tells of the mother’s illness and how he had brought his wife to Panama, fearing death was upon her, but that a kind friend, he has made on the Isthmus, has suggested that he take the invalid to Toboga. That on that island, thank God, the sea breezes are bringing health again to her mother’s cheeks.

There is but one letter more, a long one, but hastily written upon a couple of sheets of note paper. This is inside one of Wells, Fargo & Company’s envelopes, for in 1856 the express company carried from California to the East, nearly as much mail matter as the United States Government.

It reads as follows:

“Panama, April 15th, 1856.

“My Darling Mary:

“I write this because you will get it one day before your mother’s kisses and embraces. Can you understand it? When you receive this, I shall be but one day behind it—for it will come with me on the same steamer to New York; but there, though I would fly before it, circumstances are such that it will meet you one day before your mother.

“Tears of joy are in my eyes as I write; for by the blessing of God, once more I am well and happy, and so is your dear father.

“How happy we both are to think that our darling will be in our arms so soon! We are en route to New York. Think of it, Mary—to you! We left Toboga this morning.

“I am writing this in the Pacific House where we stay tonight, to take the train for Aspinwall tomorrow morning.

“The gentleman who has been so kind to your father and me, has come with us from Toboga, to see the last of us. He has just now gone into the main town of Panama, which gives me time to write this, for your father and I have remained here. It is so much more convenient for us to rest near the station, the trunk is so heavy—the trunk your father is bringing filled with California gold dust for his little daughter. I have a string of pearls around my neck, which shall be yours also. Papa bought them today from Senor Montez.”

At this Harry, who has been reading, stops with a gasp, and Louise cries: “Montez! That’s what made Montez, Aguilla et Cie. so familiar! Montez! It was the name in this old letter!” Then she whispers: “How curious! Can my employer be the man of this letter?”

“He is!” answers Harry, for while the girl has been whispering, he has been glancing over the last of the manuscript. He now astounds her by muttering: “See, here’s his accursed name!”

“What do you mean?” stammers Miss Minturn.

“That afterwards,” goes on Mr. Larchmont; then he hastily reads:

“This gentleman has been inexpressibly kind to us. George says that he saved me from death by the fever, because he took us to the breezes of Toboga.

“On parting, my husband offered him any present that he might select, but Senor Fernando Gomez Montez (what a high-sounding name!) said he would only request something my husband had worn—his revolver, for instance—as a souvenir of our visit.

“I am hastily finishing this, because I am at the end of my paper. There is quite a noise and excitement outside. Papa is going down to see what it is, and will put this letter into Wells, Fargo & Company’s mail sack, so that my little daughter may know that her father and mother are just one day behind it—coming to see her grow up to happy womanhood, and blessing God who has been kind to them and given them fortune, so that they may do so much for their idol.

“With a hundred kisses, from both father and mother, my darling, I remain, as I ever shall be,

“Your loving mother,

“Alice Louise Ripley.

“P. S. Next time I shall give the kisses in person! Think of it! Lips to lips!”

“Does not this bear a mother’s heart? “whispers Miss Louise, who has tears in her eyes.

“Yes, and the record of a villain!” adds Harry impulsively.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean this,” says the gentleman. “Last evening you told me that your mother’s parents and treasure disappeared during a negro riot upon the Isthmus on April 15th, 1856, the day this letter was written, Their gold was with them. That was their doom! Had they not carried their California dust under their own eyes, they would have lived to embrace their daughter!”

“What makes you guess this?” asks the girl, her face becoming agitated and surprised.

“I not only guess it—I know it!—and that he had something to do with it!”

“He—who?”

“Señor Fernando Gomez Montez!”

“Why, this letter speaks of him as a friend who had saved her life!”

“That was to gain the confidence of her husband, so he could betray him. Why did he ask for George Ripley’s revolver, so as to leave him unarmed? His nature is the same today! He has also betrayed another bosom friend!” says Harry excitedly.

“Tell me what you know about him!” whispers the girl eagerly.

To this, after a momentary pause of thought, Larchmont replies: “I will—I must!” And now astounds her, for he mutters: “I need your aid!”

“My aid! How?”

“Listen, and I will tell you all in confidence,” answers the young man. Then he looks upon her and mutters: “You have no interest to betray me?”

“Betray you?” she cries, “you who saved my life? No, no, no!” and answers his glance.

“Then,” says the young man, “listen to the story of a Franco American fool!”

“Oh, don’t speak of yourself so!”

“No,” he laughs bitterly, chewing the end of his mustache; “I am referring to my brother!”

“Oh, your French brother!” cries the young lady, “the one your uncle sneered about.”

“The one I shall sneer about also, and you will by the time you know him!” This explosion over, Mr. Larchmont goes on contemplatively: “My brother is not a bad fellow at heart. Had he been brought up differently, he might have had more force of character, though I don’t think it would have ever been a strong one.”

Then his voice grows bitter as he continues: “There is a school in New Hampshire, or Vermont, called Saint Regis, the headmaster of which, had he lived in ancient Greece, would have been promptly and justly condemned, by an Athenian jury, to drink the juice of hemlock, and die—for corrupting the youth of the country; because he makes them unpatriotic and un-American. This gentleman is a foreigner—a man of good breeding, but though he educates the youth of this country—some five or six hundred of them—he still despises everything American. He calls his classes ‘Forms,’ after the manner of the English public schools. He frowns upon baseball because it is American, and encourages cricket because it is an English game. He tries to make his pupils foreigners, not Americans. Not that I do not think an English man is better for England, or a Frenchman better for France, but I know that an American is better for America! Therefore he injures the youth of the United States. However, it has become the fashion among certain of our better families in New York to send their boys to his school, to be taught to despise, practically, their own country.

“Frank was sent to Saint Regis, and swallowed the un-patriotic microbes his tutor stuffed him with. After he left there, Yale, Harvard, or Princeton was not good enough for him. He must go to a foreign university. Which, it did not matter—Oxford, Cambridge, Heidelberg—anything but an American university. His guardians foolishly let him have his way. He took himself to Europe, ultimately settled in Paris, and practically forgot his own country, and became, as he calls himself: Francois Leroy Larchmont, a Franco American.

“This would not probably have weakened his character altogether, for there are strong men in every country, though when a man becomes unpatriotic, he loses his manhood; but with Frank’s loss of Americanism, came the growth of a pride that is now, I am sorry to say, sometimes seen in our country—the pride of the ‘do nothing’; the feeling that business degrades. With that comes worship of title and an hereditary aristocracy, armorial bearings, and such Old World rubbish.”

“Why! I—I thought you were one of that class!” ejaculates Miss Minturn, her eyes big with astonishment.

“Oh! You think this is a curious diatribe from a man who has been called one of the Four Hundred, a good many of whom are devotees of this order,” Mr. Larchmont mutters, a grim smile coming over his features.

“Yes, I—I thought you were a butterfly of fashion!” stammers the girl.

“So I was—but of American fashion! Now I am a man who is trying to save his brother!”

“From what?” asks Louise. “From being a French man?”

“No, from losing his fortune and his honor!” remarks Harry so gloomily that the young lady looks at him in silence.

Then he goes on: “My brother’s worship of title, his petty pride to be thought great in a foreign capital, got him into the Panama Canal, and the clutches of Baron Montez—God knows where he picked up the title. This man became my brother’s bosom friend, as he became, twenty odd years before, the bosom friend of the man whose letter I hold in my hand!”

He taps the epistle of George Merritt Ripley, and continues: “This man was a strong man. He had to be killed perchance, to secure his treasure. My brother, being a weak one, needed only flattery and persuasion.” Then looking at the girl, Harry’s tones become persuasive; he says: “I am going to the Isthmus to try and save my brother’s fortune, and that of his ward, Miss Jessie Severn, out of which they have been swindled by this man, who probably ruined your chances in life, and made you struggle for livelihood in the workroom when you should have aired your beauty and graces in a ballroom. Will you aid me to force him to do justice to my brother? Your very position, thank God! will help you to do it!”

But here surprise and shock come to him. His reference to Miss Severn has been unfortunate.

Miss Minturn says slowly: “My position?—what do you mean?”

“You will be the confidential correspondent of his firm. You will perhaps discover the traps by which Montez has purloined my brother’s fortune.”

“Do you think,” cries the girl, “that I will use my confidential position against my employer?”

“Why not, if he is a scoundrel?”

“That is not my code. When I became a stenographer I was taught that the confidential nature of my position in honor forced upon me secrecy and silence!” And growing warm with her subject, Miss Minturn goes on, haughtiness in her voice, and disdain in her eye: “And you made my acquaintance—you tried to gain my friend ship, Mr. Larchmont—to ask me to do this?”

“Good heavens! I never thought of it before these letters brought home this man’s villany to you, as well as to me!” gasps Harry “I was simply coming to the Isthmus to fight my brother’s battle, to win back for him, if possible, his fortune! To win back for Miss Severn, her fortune!”

“And for that,” interjects the young lady, “you would make me do a dishonorable—yes, a series of dishonorable acts. You would lure me to act the part of Judas, day by day, to my employer, to bring to you each evening a record of each day’s confidences! How could you think I was base enough for this? How could you?”

Then seizing the letters that have brought this quarrel upon them, and wiping indignant tears from her eyes, she whispers with pale lips: “Goodby, Mr. Larchmont!”

“Goodby?”

“Yes, goodby! I do not care to know a gentleman who thinks I could do what you have asked me!”

She sweeps away from him to her own stateroom, where she bursts into tears; for, curiously enough, it is not entirely his hurried, perhaps thoughtless proposition, that makes her miserable, and has produced her paroxysm of wrath—it is the idea that he is fighting for Miss Severn’s fortune. “He loves her,” sobs the girl to her self, “and for that reason he would have made me his tool to give her wealth.”

After she has left him, Mr. Larchmont utters a prolonged but melancholy whistle. Then he suddenly says: “Who can divine a woman? A man, thinking he had lost a fortune through this villain Montez, would have seized my hand, and become my comrade, to compel the scoundrel to do justice to us both! But she—” Then he meditates again, and says slowly: “I wonder—was there any woman’s reason for this? Her eyes—her beautiful eyes—had some subtle emotion in them that was not wholly indignation. They looked wounded—by something more than a business proposition!”

Then a sudden pallor and fright come upon this young Ajax, as he falters to himself: “Great heavens! if she never forgives me!”

Notes and References

- player: A man or woman that has more than one person think that they are the only one. Urban Dictionary.

- en camarade: in friendship. Cambridge Dictionary.

- patois: a regional form of a language, especially of French, differing from the standard, literary form of the language.

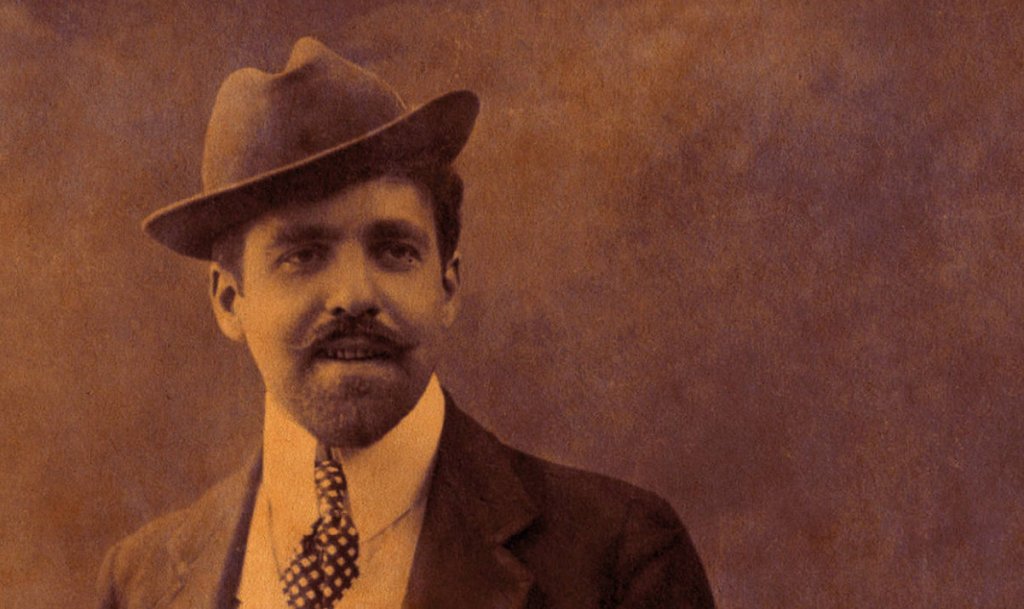

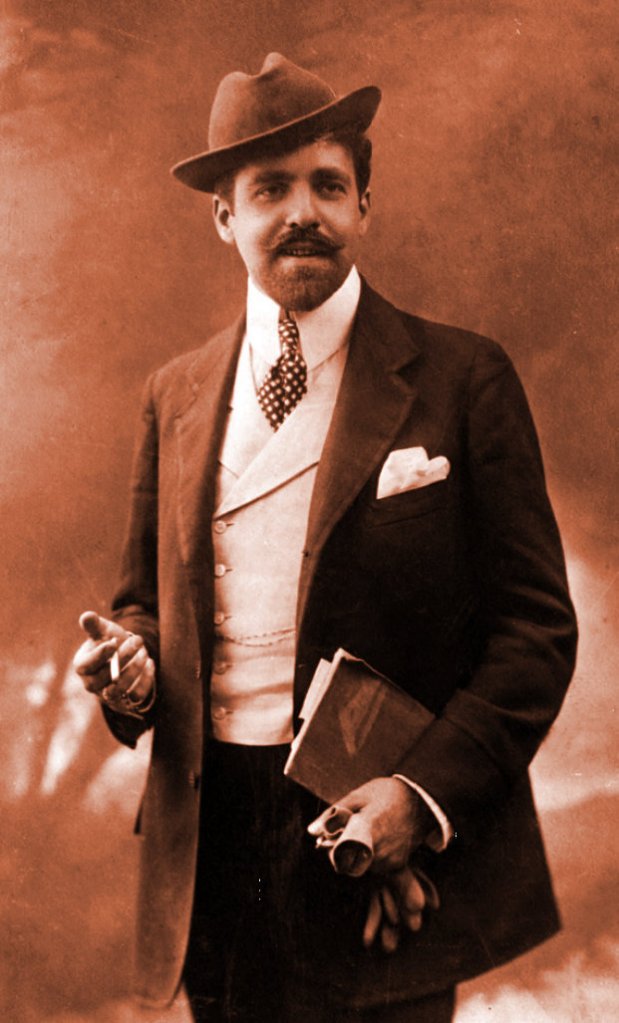

- Press photograph of male: Reynaldo Hahn (1874-1947): Venezualan singer and under-appreciated composer, conductor and music critic. Hahn was a notable denizen of Belle Époque Paris, and friend and lover of Marcel Proust.

‘Books that shaped America 1850-1900’, U.S. Library of Congress.

Phillips, A.A. -‘The Cultural Cringe’ Meanjin.

Watkins, H.L. Four Years in Europe – The Barnum & Bailey Circus – The Greatest Show on Earth. 1901. Digital Collections, New York Public Library. Jump to book

Worrall, H. , Exposing the fallacy of circus ‘showmen’.

This edition © 2021 Furin Chime, Brian Armour