Hung and festooned as it was with tablets, banners and fans, the joss house at the Chinese camp in Deep Lead was a living bubble of China in the Wimmera. House of deus, so called, from the Portuguese for god. Just inside the doorway, to the left, stood a large iron bell and a tall, barrel-shaped hand drum, with a peacock painted over the pig-skin drumhead. Beside them were glass cases containing sacred candles and five tiers of shelves holding prayers written on paper slips.

To the unaccustomed eye, the decor was gaudy, with multi-coloured pennants, Chinese characters in purple and gold painted on the walls and roof. Paper and stained-glass lanterns hung from the ceiling; bunches of tinsel in vases were set on stands carved in relief, to depict different epochs. No master craftsman created these, but they proclaim a naïve hand: work executed with painstaking devotion by a jack-of-all-trades, a long-time resident of the Chinese camp.

In her ceremonial robe adorned with all the deities of heaven to clothe her in the protection of the universe, Huish-Huish, Mow Fung’s wife, prepared the altar for the ceremony dedicated to making peace with ghosts. At the very back, raised on a pedestal, in the position of greatest honour, stands the immortal Guanyin, provider of good fortune, who is certain to help, for she hears all the cries of the world and is ever willing to offer protection from any kind of threat or attack. She sits placidly upon a lotus, attired pure white, with gold ornaments and crown. In her right palm she holds a golden flask filled with pure water, in her left raised hand, a twig of willow. Water is to ease suffering and purify the body; willow keeps evil and demons at bay. Huish-Huish communes regularly with the bodhisattva, as though she is a dear friend. She regularly brings the statue flowers, food and drink to sustain and empower her. She is no less beautiful for being made out of plaster. The neck of the statue is pierced with a hole, for other spirits to enter and represent her, after the fashion of an avatar; for Guanyin cannot be everywhere at once herself.

She lit the sacred lamp for the illumination of wisdom, then the two candles, standing for the sun and moon, and for the two eyes of the human being: the light of the Tao and windows to the psyche. These would help her penetrate the dust of the everyday world. In front of them, three cups, one each of tea, rice and water: tea for yin, the female energy; water for yang, the male; and rice the union of both of these, containing yang from the sun and yin from the earth. In front of them in turn, five plates of fruit to represent the five elements: green for wood, red for fire, yellow for earth, white for metal, black for water. These for the liver, heart, spleen, lungs and kidneys – in harmonious cooperation, a cycle of good health. Sour, bitter, sweet, salty, pungent: plum, apricot, dates, peach, chestnut. She placed dried foods on the altar on this occasion, because she wanted to absorb power from it. When she wishes to empower the altar, she gives it fresh food and flowers, from which it draws life energy.

In front of the five plates stood the incense burner, a bronze dragon turtle, the smoke curling up through the vents in the top of its carapace – vents in the form of the eight trigrams. The joss sticks were Lena’s work: Mongolian incense, pepped up with dubious substances extracted from her beloved maiden wattle. Necessary cleansing rituals completed, Huish-Huish burned the protective talismans and traced their forms in the air.

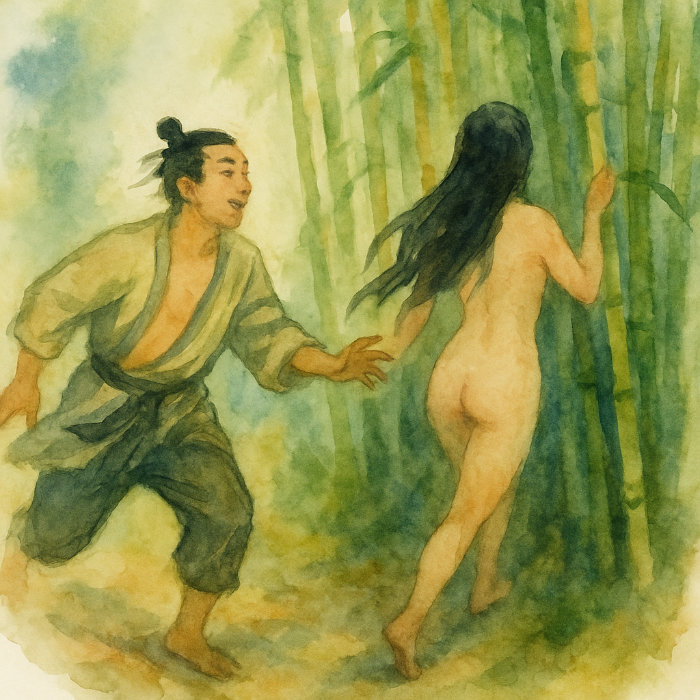

Knowing from previous experiences the ceremonial protocols, Chan Lee Lung – known in Deep Lead as Lili Chan, proprietor of the Jade Phoenix – bowed in deference as she entered, then seated herself. Huish-Huish placed a talisman on her head and performed the mudras, the hand gestures used for drawing out spirits. Based on their previous ceremonies, she has come to suspect that urges to self-harm and suicide afflicting the woman are quite possibly the handiwork of a ghost. There are any number of possible reasons why a ghost might wish the subject injury. She is a beautiful woman, and some ghost may want to marry her, particularly if she has said something inadvertently in earshot that put such a nonsense into its mind. On the other hand, it was common for the ghost of someone who died by suicide to become stranded at the gates of hell, compelled to reenact the fatal act for eternity, unless they were able to find someone to replace them, through that person’s own suicide. Or she may have crossed paths with the spirit of a suicide, or tarried at a haunted spot marked by an unnatural death. Such spirits were always in search of a victim.

The only way to get some idea is to travel with the woman as she journeys through her psyche via the medium of her speech, her story. In this way Huish-Huish may make the woman aware of the ghost, and encounter its weaker manifestations within the trance; there, the ghost itself may be dissolved or at least dissuaded. At the same time, however, in order to heal, she must make herself whole, cultivate herself, and grow in accord with the principles laid out in the Yi Jing and other Taoist teachings. No quick fix here, no game of fantan, this.

“Every child loves the pretty fable of Kwang Kau’s dream about the butterfly, which Zhuangzi teaches us,” Huish-Huish says. “When Kau awoke from the dream, he found himself unable to tell whether he was Kau dreaming he was a butterfly or the butterfly dreaming it was Kau.

“Another tale strikes me as somehow similar, in which Shadow and Penumbra converse – Penumbra wanting to know why Shadow moves as she does, perhaps because Penumbra must follow. So Penumbra says, ‘Before, you were walking, but now you have stopped. You were sitting, but now you stand up. How and why do you do that?’

“Shadow answers, ‘I have to wait for something else to move, and then I will do the same thing as it, almost as though I am its second skin …’”

The woman listens, as though to a disembodied voice – fluent, lilting Mandarin. Though her own native tongue was that of the city of Taishan – Taishonese, a dialect of Yue, kin to Cantonese – the music of the hypnotic voice draws her into its discourse, and it seems she leaves the world behind her.

“‘How on earth would I know?’ says Shadow,” Huish-Huish continued. “‘How could I possibly know what it is, that thing which moves, and which I follow – whether the scales of a snake, or a cicada’s wing? How should I have an idea why I perform one particular act instead of another?’”

The woman’s eyes are closed, and she is already on the brink of a great descent. She hears the pure tone of a chime, and the jingling of rattles, the sounds suffused with the heavy smoke of the incense.

“Like Shadow and Penumbra,” the voice continued, “I wonder whether we might allow ourselves to pass through phases of our deeper selves – or our earlier selves, when these are not the same thing – and sink into each other, you and I. Penumbras of the scales of a snake follow the shadows of the scales, which follow the snake; they need not feel the belly of the snake sliding across the sand, which is irrelevant to them and impossible to access. And to whom is visible the penumbra of a shadow of the wing of a cicada? And what does the cicada follow, when it does as it does?”

Huish-Huish aims to melt away her own ego – to become a nothingness, receptive to the projections of memory – because memory is the essence of the psyche itself.

She guided Chan Lee Lung to lie back upon a low wooden plinth set before the altar, her head resting upon a rice-husk dragon cushion.

With an austere calm, she placed fine needles along the woman’s brow, at the temples, beneath the eyes, where the face is thinner and the mind can loosen its hold. Chan Lee Lung felt no pain – only a spreading lightness, as though the weight of her features were being unhooked from memory.

After a while, Chan Lee Lung could no longer separate her inner dialogue from the sound of the guiding voice, which had transposed itself into a chant, whose symbolic words she was unable to comprehend as words, but which fell into a silence as deep as that of the deepest well. As they penetrated the surface of the ether, or whatever liquid-like substance lay at the bottom of the well, something more pure than water, the pitch darkness ignited: each word flared into a splash of sparkling light, cohering into one image, then another, then the next, setting in play a flickering spectacle. A dream that was not quite a dream; a reality that was somehow greater than her reality of the everyday. As instructed, she began to say whatever went through her mind, as though she were a traveller in a railway carriage, sitting by the window, describing to someone else in the carriage the changing scenes she saw outside.

Standing on a Canton roadside are a woman and her five children, all dressed in their best holiday black, which is nevertheless patched in some places and threadbare in others. Hardly finery, but the woman does her best under extenuating circumstances, as she repeats often to her neighbours and the grocery vendors. The middle daughter examines her mother’s face and observes a liquid bead run down along her nose and fall to the dust.

“Mama, do you cry?” she asks.

“Only sweat. Stand quietly.”

Their sign leans upright against the trunk of the slender tree under whose branches they have sought shade. The mother pacifies the baby, bounces him gently and reassures him with baby-talk, before binding him again to her back, where he falls asleep immediately. At this sight, the eldest daughter stifles the lump in her throat until the mother notices her quivering jaw and corrects her sternly. In the joss house at the Deep Lead Chinese camp, Chan Lee Lung is once again overcome with a profound sadness. Her mother was a hard woman. Again she tastes the blood in her mouth, where she bit herself on the lip to prevent herself from crying – and bites it once again.

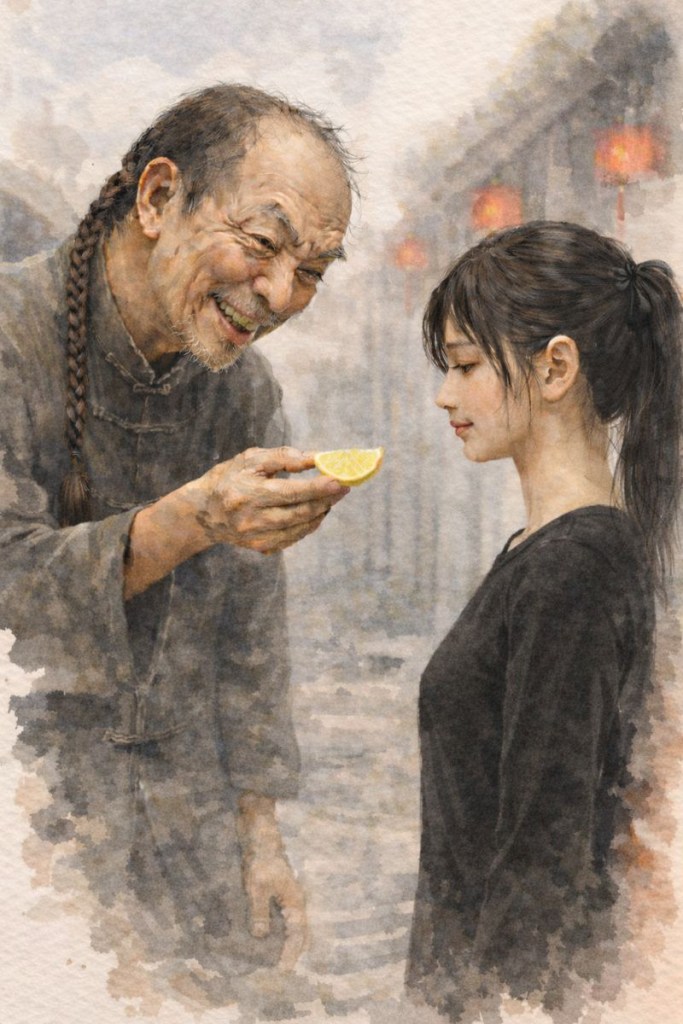

They met up with the broker, who was carrying their sign, at the appointed spot. She disliked the man’s fat, ugly, greasy face. Even his queue seemed to have lumps of fat in it, and he smelled like rotten pork. He laughed when she pointed out these shortcomings to him. He took a piece of lemon from his pocket and presented it to her. She asked him why he thought she would want a piece of lingmung. He corrected her, with another patronising laugh.

“Ningmeng,” he said, pronouncing the syllables of the Mandarin word. And again, after sucking the lemon, he repeated it, pedantically now, with his bloated, sensual, wet lips, “Ning meng.” Emphasised with two beats of his fat forefinger on her forehead. He told the girls to stand in line, with their bags arranged neatly by their feet.

She wanted to know what was going to happen to her and he replied that if she was a good girl she would go in a magnificent European ship to a wonderful place called Gold Mountain, an earthly paradise where the streets were paved with gold. There she would find boundless happiness as a wife to many men, have all the food she could eat, wear a cheongsam of the finest silk, and return to China a rich lady.

She saw the improper look he cast her mother, which he pretended was secret while intending her to notice it, a wink and leer that revealed his green teeth. She complained to the mother, saying she did not want to leave her sisters and little brother, and the mother reassured her that her sisters were leaving as well, to somewhere they would be safe from the fighting here. Her brother was too young to miss her, so she need have no concern for him.

Another man arrived by rickshaw, perused the sign, and Lemon-man took him aside to discuss a transaction. Her mother told her to take up her bag and walk with dignity to the rickshaw. She was a big girl now, and the world would be her oyster. That is all she remembers of the time her mother sold her, except that as the vehicle moved off, she looked around to farewell her mother and siblings. Her mother had her back turned, remonstrating with the broker, as was her usual way in such pecuniary transactions. Her sisters were waving to her gaily, delighted to see her riding in a rickshaw for the first time.

Two months later, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s China passed through the narrow strait into San Francisco Bay. The voyage seemed far shorter to the girl, who had been pacified with narcotics for much of the time, in order to prevent her from creating any fuss. It was a recurring delirious episode; she was rolled to and fro on her narrow bunk with the tossing of the vessel, nausea melding with visions of her sisters who, in her dreams, were transmogrified into salivating crimson ghouls. They were standing beside the repulsive man, between whose luminous green teeth issued copious streams of blood. In her waking moments, she was indifferent to the crush and squalor around her.

“This is the Golden Gate to Gold Mountain, the country of your dreams.”

The woman assigned to play the role of her mother had, during her lucid intervals, been tutoring her in what she must say in case she was questioned by someone called Customs. The girl learned to utter the English word “seamstress” while performing an appropriate pantomime, smiling with an air of great earnestness.

If her acting talents were unconvincing and the two apprehended, the White Devil would visit unspeakable torment on her.

Although the two travelled in a better section of steerage, it was only thanks to the ‘value’ her buyers saw in her looks and talents in song and dance, which they judged superior to those of their former favourite, a Hong Kong girl they subsequently cast aside. Chan Lee Lung was cloistered with a group of a dozen other girls, away from the hundreds of male emigrants and prostitutes also travelling in steerage, shielded from the rapes and bashings by two bodyguards known not for their physiques, but for their ruthless cunning and their expertise with concealed weapons.

Leaning against the railing on the starboard deck, bracing herself against the jostling crowd, the girl inclined her face to the magnificent morning sun, emerging from wisps of fog that had been thick and opaque only minutes earlier. This was the first time for the duration of the voyage that she had been permitted up on deck. The ship was about to dock when a splash was heard from the port side, followed by distinct female screams and a rising volume of anxious chatter, as a wave of agitation spread through the huddle of disembarkees. Descending the gangplank, shouldering a jute sack containing her meagre belongings, she overheard a high-pitched, trembling mention of the name Lee Sing, which seemed vaguely to resemble that of the girl in Hong Kong whose fate she had supplanted with her own.

Bound-footed Madame Ah Toy, the girl’s new owner, immediately warmed to her. When the ageing madam raised the girl’s chin with two fingers to appraise her face more closely, despite the air of sadness that still hung over her, the girl’s eyes reminded her of her own, formerly renowned for their laughing quality. Goldminers “came to gaze upon the countenance of the charming Ah Toy,” the newspaper said once, in poetic, libidinous understatement. And they would come to gaze on the countenance of this girl, her newest attraction, as well. “But only gaze for the time being,” Ah Toy said to herself, in the cold arithmetic of her trade, now satisfied the girl was physically sound, “until you’re growed up good and proper.” There was more in those eyes, however, that drew the woman’s attention: a depth of soul and intelligence; a quiet defiance that she could see would never be crushed. The madam had good reason to identify with the girl’s sterling qualities, having herself wrought a fortune as the first Chinese courtesan and the first Chinese madam of the red-light district, the so-called Barbary Coast.

Ah Toy oversaw the education of her new protégé as she would that of a cherished daughter, with a loving and stern hand. She declaimed her belief that “son without learning, you have raised an ass; daughter without learning, you have raised a pig,” and over the next few years, the girl flowered under her regime. She soon assumed mastery over the various academic and dance hall pursuits for which her tutelage had been commissioned, guided by professorial clients of Ah Toy’s famous establishment in an alley off Clay Street, under contracts of barter.

The girl’s getting of wisdom served, as ever, a financial motive, for the ladies of the Chinese establishment trailed those employed in French, Mexican, British and American cat houses, whose popularity ranked roughly in that order. Competition was fierce in the bagnio trade. The French fandango parlour had its les nymphes du pavé, late of the Parisian gutters, who were packing in the patrons to overflowing, gussied up in their red slippers, black stockings, garters and jackets, nothing down below. Stories abounded of outrageous personalities: The Roaring Gimlet, Snakehips Lulu and the rest. Holy Moses! Madame Featherlegs would gallop a horse down the main street wearing nothing but batwing chaps.

Unfortunately, although a successful entrepreneur, Ah Toy had also become rather a laughing stock, largely because of her Chinese-ness, but also because of the young age and sickly condition of the girls crammed into her shacks, or “cribs,” in Jackson Street, sometimes abused by white boys scarcely older than children themselves.

These girls she considered, and treated, no better than chattel.

The girl grew into her role admirably, expressing as though they were natural traits the aristocratic airs she was schooled in; airs that in fact derived from no single country, but from an amalgam of places, real and imaginary. Yet somehow her intrinsic class seemed to imbue these artificial attributes with substance.

She was not overawed by anyone she met, but treated with due respect and equality all who crossed her path: from city officials who surreptitiously joined the growing flood of patrons paying good money for no more than the pleasure of gazing upon her, to slave girls locked in the cribs like animals. Most of these girls had been smuggled from China, either peddled, like her, or abducted outright. Sufferers of syphilis numbered among them, their short futures preordained: to die disfigured beggars on the streets of Chinatown.

She felt a compassion for these creatures in the cribs, pleading their cause to Madame Ah Toy and doing her utmost to convince her, in terms she would understand, that acknowledging even minimal duties of care to the crib girls might serve her business-wise – allowing her to be perceived as less of a pariah and blight on society, though she couched that more gently.

No cribs for her, nor even a residence in one of the sumptuously appointed parlour houses. Ah Toy set her up in a double storey brick house of her own, where she entertained only the most prestigious clientele – exclusively white, expressly no Chinese – when she was not assisting her proprietress to operate the gambling house and manage the business affairs. As well, Ah Toy provided her with a chaperon, a certain Fung Jing Dock, whom she introduced to Chan Lee Lung as an office bearer in a newly formed organisation known as the Society of the Mind Abiding in Tranquility and Freedom. He was, Ah Toy said, a virtuoso on the zither as well as an avid student of the Yi Jing.

“Regarding my degree of talent with the zither, I must refuse to answer,” Fung Jing Dock pleaded charmingly, “in order to avoid incriminating myself.”

Nevertheless, he proved to be a surprisingly good amateur zitherist, and Chan Lee Lung and he spent a few minutes at the instrument together now and then during the daylight hours.

“But there is more to this story,” Lili Chan said as they came out of the joss house and into the dazzling sunlight. “It does not end well, I’m afraid.” She turned towards her establishment.

Huish-Huish looked at her face, which seemed pallid.

“As a process, the ceremony may sometimes require any number of iterations,” she said. “Some subjects joke that it will go on forever, and they will never be free of me. Things cannot be rushed, however. We will have plenty of opportunity next time.” She laughed. “There is no cure for the human existence, you know,” she said. She briefly squeezed her companion’s arm and went back briskly into the joss house. Pausing to look up at the empty expanse of sky for a second, Lili took in a long breath, before making her way languidly down the street.

From the draft novel Stawell Bardo © Michael Guest 2026