Welcome to the final dramatic chapter of Baron Montez of Panama and Paris. We witness the culmination of Louise and Harry’s romance and the end of Fernando Montez. Readers have been eagerly anticipating the final revenge against Montez, for every time they pick up the yellow-back novel to read, the cover screams of the lustful, violent crimes he committed.

Be prepared to be confronted by how the romance of Louise and Harry is treated. For the purposes of securing the desired outcome, Louise must be transformed to meet current societal standards. First, she is coerced, softened by the presentation of three dresses, and as the evening progresses the reader will observe her become increasingly objectified. The narrator is literally lost for words in describing her appearance. Louise is for the most part quiet and acquiescent during the chapter though she strives to maintain her integrity and independence.

Harry recalls the Roman writer, Livy’s depiction of the rape/abduction of the Sabine women by Romulus to satisfy Rome’s need for females, as if this is a historical precedent for his forceful behaviour towards Louise. Readers of today will be familiar with the scene, it having been re-enacted in various forms in films, for expressing a man’s power over a woman. Louise can’t get a word in, and so far as Harry’s ‘proposal’—he even has the hide to accept it on her behalf.

The mention of ‘marriage settlements’ may recall from my introduction to Chapter 7 (“NO! BY ETERNAL JUSTICE!” ) the definition of ‘coverture’: the legal doctrine that treated a married woman’s possessions, wages, body and children as property of her husband, available for him to use as he pleased. Coverture gave husbands total control. The use of the word ‘guide’ by both Jessie and Louise is an attempt to mollify the true master/subordinate relationship. After their marriage, Louise asks Harry for permission to spend her money.

However, though cast through a male point of view, there is an alternative reading mired in the eternal struggle of relations between men and women. Post proposal, Louise says: ‘I shall give you even more trouble than Jessie’, and prior to the evening’s events stated that she would ‘put her best foot forward’. It is not beyond imagination to suggest that Louise has done exactly that, and her show of independence, her steadfastness, is a deliberate move to force the dunderhead Harry to act.

The pre-marriage arrangements and indeed the marriage itself are treated summarily and finish with a honeymoon in Italy.

The second part of the chapter dealing with the last moments of Fernando Montez is done in retrospect, similar to the previous chapter, only with the return of Frank to the door of the apartments late at night, having previously escaped his bodyguards. Two other enemies of Montez are present in the final moments. It would be a shame to reveal too much detail—suffice to say that Gunter handles the last moments of our protagonist, at the hands of his former prey, in an imaginative and efficient way.

The novel has used the French attempt at the construction of the Panama Canal as a background to the adventures within, but the timeline of the story, unfortunately, cannot contain the full extent of real events. Before his demise, Montez assumes that, with the Lottery Bill having passed the Senate, outstanding debts to him for contracts associated with the Canal will be paid. In truth though, this is unlikely. It will take two months of preparation before the Lottery shares are put to the public for sale. On the 11th December, a day before the last day of the sale, Ferdinand De Lesseps himself takes the stage in the hall of his company, which is packed full of desperate investors and declares:

‘My friends, the subscription is safe! Our adversaries are confounded! We have no need for the help of financiers! You have saved yourselves by your own exertion! The canal is made!’

Ferdinand De Lesseps, qtd. in Parker, p183

De Lesseps leaves the stage in tears and embraces the cheering crowd. The following day Charles De Lesseps, his son, fronted a similar crowd. He informed them that of the 800,000 bonds on offer only 180,000 had been sold, and this being under the minimum requirement, all deposits collected would be returned. This led to the eventual liquidation of the company (Parker, p. 184)

At the close of the novel is a small epilogue, more an aspirational scene for readers, for the fulfilment of the American Dream. The three major characters stand on a hill looking towards an optimistic future. Louise now has the fortune she should have had all along, and this together with her marriage to man-about-town Harry, has placed her in the social position where she felt she always belonged. The last words are spoken by Frank, who in his derangement mistakes a naval parade on New York’s Hudson River for the opening of the French Panama Canal—of course, an event that in reality never occurs.

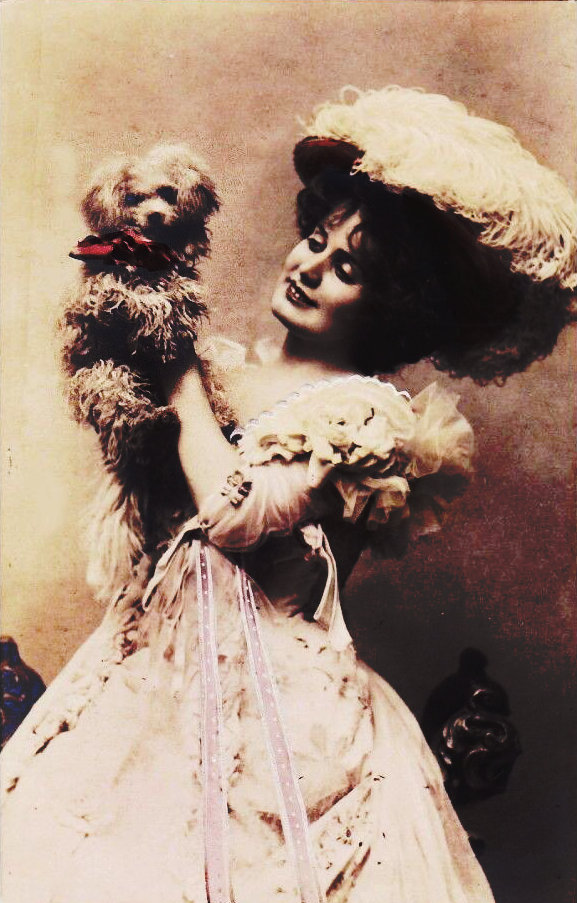

Gunter’s career as a dramatist is reflected in the style of the novel. The previously mentioned objects, such as the enamelled box or the black pocketbook might be props, and Gunter is excellent at staging interactions between characters, and of course, his facility with dialogue is the mainstay of the novel. Consistent with this, perhaps because it would be right before the eyes of an audience watching it on stage, are minimal physical description and use of colour. Apart from descriptions of the flowers of Tabogo Island and the sunset over the rail of the SS Colon earlier in the novel, and Jesse’s blue eyes, the use of colour is limited. The reader may have noticed an absence of descriptions of interiors, the colours of dresses, how Louise wears her hair, what colour it is, or her eyes—all are missing. Also, there is little incidental interaction of characters with their environment. In a sense, Gunter’s work can be viewed as a precursor to film scriptwriting.

In closing, I would like to thank all the readers who have joined me on this journey through this work of Archibald Clavering Gunter—through the time and world his characters inhabited a hundred and thirty years ago. I would also like to thank Michael Guest for giving me the opportunity to write for Furin Chime and for assisting me edit the text and select images.

CHAPTER 25

THE PREFERRED CREDITOR

Then Mr. Larchmont looks at his watch. He has just time. He springs upstairs to the door of Louise’s room, raps on it, and would shout: “Victory!” but the girl knows his step, and is before him. His face tells its own tale.

She cries: “You’ve won! Thank Heaven! I—I am so happy for you.”

“Yes, we’ve won!” answers Harry—“won in full! But to nail our flag over his—I must go at once—I have just time to do it! Goodby—our interview this evening!” His voice grows very tender, and wringing her hand, he mutters: “God bless you! It was all you!”

By this time he is down the stairs, but at the foot of them he turns and cries: “I’ll attend to your dress!” then opens the front door, springs down the steps, and gets into his brother’s carriage, which has been waiting for him for the last hour.

In it he drives, with even more than Parisian recklessness, to his American lawyer, Mr. Evarts Barlow, and getting him into his carriage, the two post off to the Paris agents of the New York bankers who hold the American securities of Fernando Montez. At their suggestion, the agency cables their home house, that all the stocks, bonds, and investments of Baron Montez in their hands have been transferred and made over to Harry Sturgis Larchmont, by personal deed of their former owner, properly acknowledged and registered, which they (the agency) now hold; that all further dividends upon said securities, earned now or in future, are to be paid in to Mr. Larchmont’s account, at his bankers in New York.

This being done, Harry remembers he has another errand, and telling it to his lawyer, the latter laughs: “What?—Parisian modiste, so soon!”

“Certainly! She’s worn one dress three days running!” replies Harry. Then he says, in a voice that makes Barlow glance very sharply at him: “She’s like a dream in muslin! What will she be under the genius of a Worth or a Felix? You’ve a treat before you tonight!”

So it comes to pass that, about four o’clock this afternoon, a forewoman of a great Parisian dressmaker calls upon Louise, and presents a note which reads:

My Dear Miss Minturn:

With this I send you some robes to choose from. You need not fear the expense. If you take them all, they are easily within your income. I’ll explain the financial part of it this evening. I’ve nailed everything—by your aid.

“Yours most sincerely,

HARRY LARCHMONT.

P. S. Please, for my sake, put on the prettiest tonight. The great lawyer I told you of will call with me—upon your business.”

This kind of a note dazes the girl. The dresses displayed to her delight but astound her. In her present state of mind, she would send the woman away and tell her: “Tomorrow—any other time!” But Harry’s note says: “For my sake!”

So Louise looks over the robes, and now the legacy left her by Mother Eve comes into play. The dresses fight their own battle; for they are exquisite conglomerations of tulle and gauze—the tissues and webs of Lyons thrown together by a genius for such effects.

Just at this moment Jessie adds her efforts to this scene. She comes in and chirps: “My! How lovely!” and looks over the gowns with exclamations of delight, but not of envy. For she cries: “How beautiful you will be this evening!”

“This evening! Mr. Larchmont has written you?”

“Yes—this unsatisfactory note, half an hour ago,” pouts Jessie. It only says: ‘Have a nice dinner for four this evening at eight sharp. I shall bring Mr. Evarts Barlow with me.’ Evarts Barlow?—he is one of the great lawyers of Manhattan. I saw him last season. He’s not so old, either,” goes on Jessie, contemplatively. “I think I’ll put my best foot forward. I’ve got some dresses of the Montez trousseau that are rather comme il faut, I imagine. I’ll go at that trousseau and wear it out quick, before I’m promised again. It shan’t do double duty!”

She goes away, and Louise, thinking of Miss Severn’s remarks about putting her best foot forward, says to her self: “Why should not I do the same? My foot is also a pretty one, I believe!” Then she laughs, for there is something in all these remarks of Mr. Larchmont’s and Jessie’s, that brings a sudden spasm of doubt to an idea that had burned itself into her brain in those hot days on the Isthmus, when Harry had raved in the delirium of the fever.

Then Mother Eve flying up in this lovely creature, with the assistance of the forewoman, who is very expert in such matters, Louise finds herself in such a toilette by dinnertime, that, looking on herself, she is amazed, per chance a little awed, by her own image; for she is a dream of fairy beauty.

So Miss Minturn coming down into the great parlor of Franc̗ois Larchmont, with its wealth of bric-a-brac, statues, and paintings, Jessie runs to her and says: “Don’t we contrast just right!—only you overpower me—you have so much esprit!” for Jessie has a dear, generous heart, and there is a great soul in Louise’s eyes this night.

As they stand together, two gentlemen in evening dress enter and gaze upon them amazed.

“Great heavens, Larchmont!” whispers the lawyer to Harry. “Why didn’t you tell me I had such pretty clients? I would have worked for them as if inspired.”

“I—I didn’t know she was quite so pretty, myself!” mutters Harry, who has eyes for only one of them.

A moment after, the introductions are made, and Barlow and Jessie, followed by Louise and Larchmont, go in to one of those pretty little dinners, that are all the more pleasing because they are not quite banquets.

As they sit down, Miss Minturn’s thoughts give a jump to the time she first saw the gentleman beside her in evening costume—to the night of the dinner party at Larchmont Delafield’s, when she was not guest, but stenographer. Then recollections bring blushes. It is her pretty shoulders Mr. Larchmont is now looking at, not Miss Severn’s.

Into this reminiscence Jessie breaks: “Guardy Harry, have you got me into your clutches thoroughly? Are you legally my guardian now?”

“Yes!” replies Larchmont. Then he looks curiously but anxiously at Louise, and says: “I am also the guardian of another young lady!”

“Another ward? You wholesale guardian; who is she?” laughs Jessie.

“Miss Minturn!”

“I!” gasps Louise, her eyes growing astonished and almost affrighted.

“Why, certainly!” remarks Barlow. “I had the order of court made today. You’re only nineteen?”

“Y-e-s!”

“Then not of age in Paris, though you may be in America. It was necessary for the proper protection of your interests and property, that a guardian should be appointed. Heiresses must be looked after.”

“Heiress!—I—?” stammers Louise.

“Of course,” interjects Harry, “if you don’t like it, you can have someone else appointed tomorrow—Mr. Barlow, for instance—but for tonight,” he rises and bows profoundly to her, “I believe I have the honor of being your guardian and your trustee.”

Here Jessie suddenly exclaims: “Both Harry’s wards! Delightful! Louise, we can do our lessons together and have the same governess. Half of the present one will be enough for me!”

“Jessie!” cries Larchmont, sternly, for Louise’s eyes have looked rebellious at the mention of lessons and a governess. “Miss Minturn is a little older than you. This appointment is more form than otherwise.”

“Oh!—Well, it don’t matter being Harry’s ward,” giggles Miss Severn. “He is a good, indulgent guardian. He lets you do as you like. But if it was Frank!—Whew!—Louise, he might decree that you were only eleven or twelve years old tomorrow morning!”

“And if you were sullen, kodak you,” interjects Harry, grimly.

But a scream from Jessie interrupts him. “Oh, goodness!” she ejaculates. “He didn’t get a picture of me!”

“Yes—a very charming one. It is labelled, ‘L’enfant gâté’. You look as if you were springing at the camera.”

“And so I was!” mutters poor Jessie. “I thought he had not snapped it in time. Did he really get one?” The tears come into her eyes, and she begs: “Please don’t show it—Please——.”

“Not if you’re a good, obedient little girl!” says Harry, with great magnanimity.

As for Louise, she has been silent during this. The word “heiress” has put her into a kind of coma; the term “guardian” has given her a fearful start, and sometimes her eyes look at Harry Larchmont in a half-bashful, half-frightened sort of way.

Then the conversation runs pleasantly on, Harry telling Barlow of his Isthmus adventures; some of his stories making Miss Minturn, who has gradually been regaining her intellect, blush, though they make her more tender to the man relating them, for they bring back the days she had struggled for his life by his bedside in the room of young George Bovee.

This talk of the Isthmus leads to talk of the Panama Canal, Barlow remarking: “The Senate will probably pass the Lottery Bill tonight.”

“That will give the enterprise six months longer to exist, I imagine; but more empty pocketbooks and more bankrupt stockholders, when the inevitable crash comes,” rejoins Larchmont. “By the by, I wonder if the Baron is looking after it this evening! Eh, Jessie? What would you have said to journeying to Italy about now, with his chocolate face beside you?”

At this Miss Severn shudders, grows pale, but says firmly: “He has kinks in his hair. I would have said, ‘No!’ right in his face, to both notary and priest.”

With this, as the dinner is over, Miss Jessie rises, and going to the door, turns, and lifting her skirts a little, courtesies, after manner of dancing school children, and says: “I bid you adieu till après le cigar, my guardian!”

And Louise, who has risen also, a kind of reckless mirth coming to her, follows Jessie’s example, and, courtesying to the floor, murmurs: “Your obedient ward, Monsieur Larchmont!”

Then the two go off laughing towards the parlor, leaving the gentlemen to cigars and coffee. But they don’t take very long over these, for Barlow says: “We owe a little explanation to Miss Minturn about her affairs.”

To this Harry replies: “Very well! Let’s get it over!” a curiously anxious look passing over his face.

Then the two coming into the parlor, Mr. Larchmont takes Jessie aside, and whispers: “Would you mind running upstairs for a little? Mr. Barlow and I have some business with Louise—Miss Minturn.”

“Shall I not come down again?” falters Jessie.

“No, perhaps you had better not. Perhaps it would be well to bid Mr. Barlow good evening now! I imagine you have lessons to learn!”

At which Miss Jessie astonishes him. She says: “Yes, and you have something to say to Louise. But—I’ll be down to congratulate!” and so with a bow to Barlow moves out of the room.

Then Harry and Mr. Barlow go into a business conversation with Miss Minturn.

Mr. Larchmont says: “I have received a number of millions of francs in trust for three creditors of Baron Montez. You, Miss Minturn, are the preferred creditor. Your dividend first!”

“My dividend on what?”

Here the lawyer remarks: “You are the sole heir to your mother, and she was the sole heir of her parents. They were robbed, I understand from Mr. Larchmont, of sixty thousand dollars on the Isthmus, in 1856. This at interest at six per cent., for thirty-two years, compounded yearly, amounts to nearly four hundred thousand dollars—two millions of francs.”

“Oh, goodness!—So much?”

“Certainly!” answers Harry, “I’ve computed it!” and he bows before her, and says: “Behold another American heiress!”

Here Louise astounds the lawyer and stabs Harry to the heart. She says in broken voice: “You, Mr. Barlow, take it for me—you be my guardian. You can be appointed tomorrow!”

“Good heavens!” cries Larchmont. “What have I done? Can’t you trust me?”

“Trust you? Of course I can!” murmurs Louise; “but two wards will be too much for you to guide.” Then she says faintly: “Yes, let Mr. Barlow be my guardian—take care of my money—I’ll leave it to his judgment!”

“Of course, if you ask it I can hardly refuse,” returns the lawyer; “but you had better think over it till tomorrow.”

And noting that the girl is strangely agitated, Evarts Barlow remarks: “I will go now, and see you in the morning. Your interests this evening are thoroughly safe in the hands of Mr. Larchmont!”

So this diplomat makes his bow, and taking Larchmont with him to the hall door, he whispers: “This . strain has been too much for your pretty ward. If you’re not careful, she’ll require the doctor, not the lawyer! I’m afraid she has wounded your feelings.”

“My heart!” replies Harry, with a sigh. And Barlow bidding him adieu, Larchmont marches in to his fate, and goes into the great parlor where Miss Minturn stands, more beautiful than ever before this evening.

It is the beauty of resolution.

As he looks at her, the laces and tissues clinging about her exquisite figure are so still, she would seem a statue, were it not for the quick heaving of a maiden bosom that throbs up white and round and trembling beneath its laces, and a little nervous twitching of lips that should be red, but are now pale. There is a fear in her eye She uplifts a dainty hand almost in warning, for he has come up to her, pride upon his face, agony in his heart, and anguish in his eyes, and said sternly: “How dare you do it?”

“Do what?”

“Refuse to accept me as your guardian! Imply I was not worthy of the trust—I, who think more of it than any man upon earth!”

“Oh,” says the girl, “I presume I can choose my mentor—I have arrived at years of discretion enough for that!” Then she falters: “Let me go away! I—I have saved your bride for you!”

“Have you?” mutters Harry, surlily. “That’s some little blessing!”

“Yes—let me go away.”

“Not out of this house tonight!”

“Why not?”

“Because I forbid you! “answers Harry. “Tomorrow you may have Barlow—or anyone else you like—but today the courts of France made me your guardian—and tonight you obey me!”

“You forget—tomorrow—you are not my guardian then! Let me go! May you be happy!” And, fearing for herself, Louise glides towards the door. But his hand is upon her white arm, and his voice whispers: “Not without me!”

On this the girl pulls herself away, faces him with eyes that blaze like stars, and stabs him with these cutting words: “Do you want to compel me to run away from you as I did from Montez that awful night?”

“Why won’t you have me for your guardian?”

“One ward is enough!”

“Ah! You are jealous of Jessie!”

“Pish! Of that child?”

“Yes—jealous of her!” answers Harry, who has discovered that the Roman way is the only true method of winning this Sabine virgin. Then he astounds and petrifies her, for he murmurs: “You love me!”

“I? My Heaven! How dare you?” And the girl is before him with flaming eyes.

But he smites her with: “Because I have your DIARY!”

“Impossible!”

“Yes, from Mrs. Winterburn in Panama!”

“Ah! the traitress!” Louise’s hands fly to her affrighted face; she bows her drooping head, tell-tale blushes cover her face, her neck, and even her snowy shoulders, making what had been glistening white, gleaming pink. But she forces herself to again look at this man, and her eyes seem to be scornful, and disdain is on her lips, as she mutters: “And you dared to read it?”

“No!”

“Then how did you discover——?”

“Ah! I have you—ah!”

“O Heaven!”

“A bunch of violets and a card dropped out of it—my tokens of the blizzard. They were mine before—they are mine now!” cries Harry, and pulls them out of his breast and kisses them. Then he says tenderly: “I stole your confession—I give you mine! I love you with my soul! good angel of my life—whose scorn kept me from making a fool of myself in Panama—whose kind nursing saved me from the fever! I love you! Without you for my wife, life has but little for me—what does the kind nurse—who saved it in faraway Panama:—say?”

And Louise stands fluttering before him—loveliness personified—loveliness astounded—loveliness in doubt—loveliness blushing—loveliness that is about to be happy; for a sturdy arm that has played in many a football game is round her waist, and is giving her such a grip as never Princeton man received in college jouissance.

The girl gives no answer save a little sigh; she has almost fainted in his arms. But a moment after, her happy eyes seek his, and she falters: “Was it only to save your brother? Was it only to save your fortune you went to Panama?”

“That at first,” answers Harry, stoutly. “But afterwards I fought to be rich enough to put you in the place in society that you will adorn!” Then he queries: “Shall I continue to be your guardian? Shall I tell Barlow he need not oust me in court tomorrow?”

“Since you are going to be my permanent guide,” returns the young lady with a piquant moue, “I suppose you might as well get into practice as my guardian.”

“Then may God treat me as I treat you!”

There are tears in her beautiful eyes, there are kisses on her cherry lips, as Louise says playfully: “Dear Guardy! I shall give you even more trouble than Jessie!”

“Then I will cut my guardianship very short!” cries Larchmont, a gleam of joy flying into his face as he walks up to the girl, who can’t now meet his eyes, as his arm goes around her waist again. For he says: “I, Harry Sturgis Larchmont of New York, demand of you, Harry Sturgis Larchmont, at present of Paris, the hand of your ward, Miss Louise Ripley Minturn, in marriage! And I, Harry Sturgis Larchmont, guardian of said young lady, accept your proposition, my worthy young man, for I have a deuced good opinion of you, and solemnly betroth her to you, and announce that the nuptials shall take place WITHIN THE MONTH.”

“Within the month!” falters Louise. “But I have only known you four!”

“Yes, but guardians must be obeyed!”

Then there are more kisses, and Mr. Larchmont walks out, and mutters to himself: “By Jove! that was a harder battle than I had with the Baron this morning!”

About half an hour afterward, meeting his friend Barlow at the Café de la Paix, he says: “You need not make any motion about that guardianship business! The young lady has had the good taste to accept me, after all!”

“As a guardian?” asks Barlow, in tones of cross examination.

“As a husband as well!” remarks Larchmont, “and the sooner you get to work at the wedding settlements, the better it will please both the guardian and ward.”

The next morning Mr. Larchmont, coming from his apartments on the Boulevard Haussmann, takes Louise, and says to Jessie quite solemnly: “This young lady is to be my wife. As the wife of your guardian you will obey her, eh, rebellious one?”

But Jessie gives a mocking bow, and laughs: “Oh, I know all about it! She told me last night! We have been talking about you most of the time since. I have promised to be obedient, if she asks me to do just what I want to!”

“Ah!” replies Harry, “then I shall exhibit the kodak.”

And Jessie cries: “No! no!”

But he is in a merry mood, and shows the picture of l’enfant gâté’. to Louise, and they all laugh over it.

But though Jessie giggles, she also begs; so piteously he gives it to her. Then she tears it into a hundred pieces, and tossing them over her head, dances on them, crying: “That’s how I leave my childhood behind me!” next says: “No more governesses! Eh, Guardy?” with a pleading look.

“AFTER the wedding!” remarks Mr. Larchmont, for he has thought upon this subject, and he has concluded that a governess for Jessie will be very convenient during the honeymoon.

But the next morning he is relieved to find Mrs. Dewitt has returned from Switzerland. He introduces her to his coming bride, and this lady is most happy to take charge of Miss Jessie during his wedding tour.

In one of their numerous communings, within the next day or two, Louise says to Harry: “We are so happy! Can’t we do a little to make others happy?”

“To whom do you refer?”

“To a dear little friend of mine in New York, who is going to be married also, Miss Sally Broughton,” answers Louise. “Could I send her a thousand dollars?”

“Of course! ten thousand if you like. It’s your money, dearest,” answers Harry, cheerfully.

“Oh, thank you!” replies Louise. “A thousand is enough. It will mean a great deal to Mrs. Alfred Tompkins.”

“So Sally is going to marry Tompkins!” remarks Larchmont, grimly. Then he suddenly continues: “Tompkins was the man who shook his fist at me when he saw me sail away on the Colon with you? Eh?” and his eyes ask awful questions.

“Y-e-s!”

“Ho-oh!” Then Larchmont smiles a little and says: “Any other gentleman you want to do a good turn?”

“Yes, to George Bovee, who nursed you on the Isthmus so tenderly—who was such a good chum to you out there. He is growing pale also—someday he may have the fever, and there will be no one to nurse him. Could not you?—you need someone to manage your affairs—” For Harry had been complaining about the amount of business that had suddenly come upon him, from his brother’s incapacity.

“Oh, I cabled George yesterday; he is now on his way to Paris!”

“On his way already?”

“Yes, so as to be my best man.”

“Oh,” cries Louise, “you are always talking of the wedding!”

“Of course! I am always thinking of it!”

Probably Louise is too, for she and Jessie are driving about town, from milliner to dressmaker, and dressmaker to jeweller; and all the gorgeous paraphernalia of a mighty trousseau is being manufactured in this the town of trousseaux, as fast as nimble fingers of French working women can put together things worthy of the beauty of the bride.

So one morning, at the American Legation, Louise Minturn is married to Harry Larchmont, and Evarts Barlow, who has stayed over for the ceremony, gives the bride away. George Bovee stands behind his old chum of the Isthmus, with Miss Jessie, the only bridesmaid, but with the concentrated beauty of six average ones in her pretty self.

Then bride and bridegroom go to Italy—southern Italy and the isles of the Mediterranean—where they see palms and orange trees, and dream they are in Panama—but there is no fever! And coming back from this trip, they linger out the happy autumn time in Paris.

But one evening Francois Leroy Larchmont, in a careless moment of his keepers, escapes from them, and is out all night. The next morning, he comes back with a sleepy look upon his face.

But Harry Larchmont, reading the morning journals, gives an awful start! Two days after, the whole party are en route for America, taking the brother, whose mind is now permanently gone, with them.

* * *

Crushed, defeated, but not altogether subdued and dismayed, Baron Montez staggered down the steps of the Larchmont mansion.

The next day he calls at the American embassy, and delivering up his order, receives, after identification, a sealed envelope, which he tears open, and finds his pocketbook—not one memorandum gone, and his eyes glisten.

He thinks: “With this I have enough to feed upon the vitals of this republic. Some of their public men are in my power!” Besides, his fortune, outside of his American investments, is large, and the Lottery Bill almost immediately passes the Senate of France and becomes a law. He receives large sums of money, delinquent payments due from the Canal Company, and though he is forced, by the record of the ledgers Louise has taken, to make some restitution to Aguilla, still, as he does not make restitution to anyone else, his fortune is enormous.

Though the shares of the Canal go down and down, he has no interest in them, and lives the life of a gay bachelor in Paris.

In the course of time, the deluded investors will take no more lottery bonds, and in December an assignment is made to a receiver, and the work practically stops on the Canal Interoceanic.

As this happens, Fernando Montez becomes possessed of a shadow. Though he does not know it, as he walks along the boulevards, a shabby creature slinks along behind him. When he goes to the opera or theatre, the creature is waiting for him as he comes out. This unfortunate one evening stands outside the gay Café de la Paix, with its flashing lights, and sees Montez eating the meal of Lucullus. As Fernando comes out, well fed, contented, even happy, this shabby creature mutters to himself: “Nom de Dieu! for his dinner he paid more money than I saved in my whole first year of deprivation!”

And Bastien Lefort, the miser, who has been sold out of his glove store on the Rue Rivoli, utterly ruined by his grand investment in the Canal Interoceanic, follows, shivering with cold, and brushing the snow off his rags, the steps of the well-dressed, debonnair, and happy Baron Montez.

But there is another—a black man with snowy wool, and two great red gashes upon his cheeks, and a form bent by age, but strong with hate. He comes alongside Lefort and whispers: “How now, miser! Are you on the track of your enemy? I, Domingo of Porto Bello, have come a long way to see him, also!”

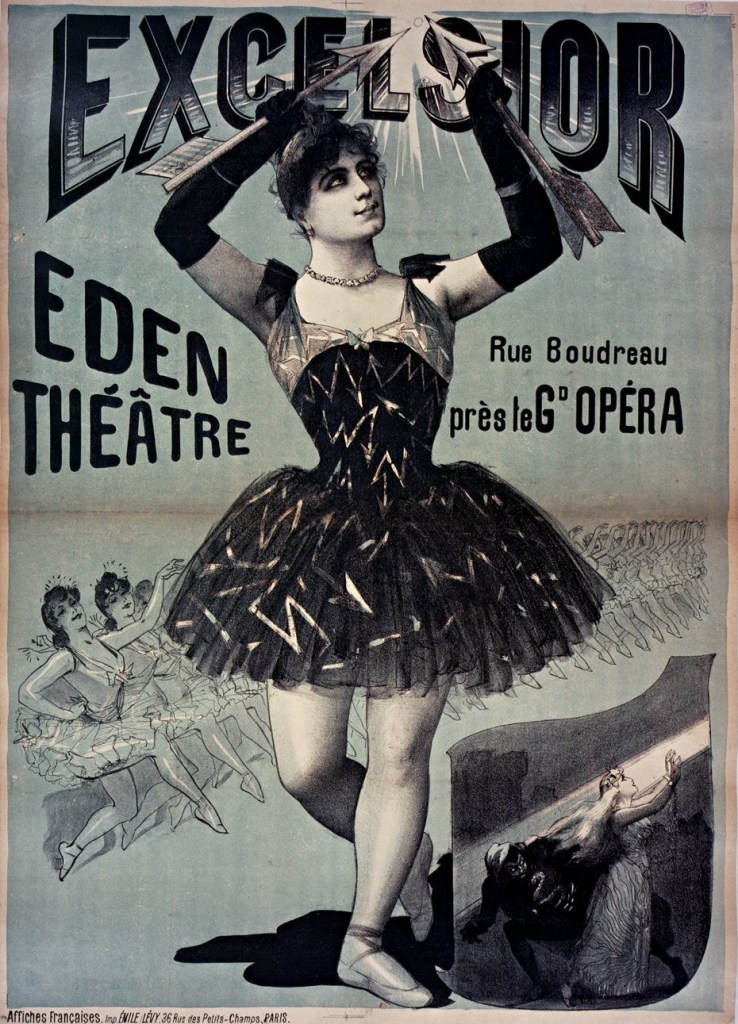

And the two become bloodhounds, and follow the Baron Montez of Panama all that evening to the haunts of gay bachelors in Paris: to the Eden Theatre, where there is a ballet; to the Palais Royal, where he laughs at a suggestive farce. But whenever he comes to the streets—these two dog his footsteps.

So it comes to pass, late that night, returning from a petit souper with some fair sirens of the gay world of Paris, who are very kind to rich men, Montez enters his apartments, to find his valet is not in them, and mutters to himself:

“The worthless beast! I will discharge him tomorrow!”

Then Fernando sits down to await the coming of Herr Wernig; for these two are hunting in couples again.

So Montez meditates and is happy; but, chancing to think of his lost American securities, he utters a snort of savage remembrance, and taking the poker in his hands breaks up the coals burning in his porcelain ornamental stove—and as the blaze flickers up, thinks he sees a face. He starts and gazes round, and sees three faces—the faces of the wronged, the faces of the past—Domingo’s pirate head, the miser’s wistful face, and the pallid cheeks and big eyes of the lunatic, Franc̗ois Larchmont.

Fernando thinks it a dream. The lunatic says with cunning chuckle: “I enticed your valet away, my dear Baron—ha, ha!—and let myself in with my old passkey—you forgot the passkey—ha, ha! I was coming in here to do your business myself—but these two gentlemen joined me—ho! ho! ho!”

THEN MONTEZ’ DREAM BECOMES REAL!

He springs up to cry out and defend himself—but the lunatic’s hands close round his throat, and the voice of a madman cries: “Oh, ho! my friend! Baron Montez of Panama and Paris!”

And though Montez struggles he cannot say anything, and his eyes have despair in them, for three men have surrounded him. He sees, half in a dream, the form of Domingo, the ex-pirate, whom he has robbed, who whispers in hoarse voice: “Ah, ha!—the punishment of the buccaneer—who steals from his fellows!”

And the miser cries: “For the gold of my ruined life!”

Then a surging is in his ears; there is the report of a pistol, and three forms glide out into the darkness; and on the floor, his own revolver in his hand, lies the form that was once—Baron Montez of Panama and Paris!

A few minutes after, his old chum, Alsatius Wernig, comes in with laughing voice and merry mood, crying: “Oh, ho! my dear Fernando! you leave your door open. You should be careful! You might be robbed!” then utters a horrified “Mein Gott!” and staggers from the prostrate form before him. Next he says slowly, with pale lips: “Murder! If they have stolen the pocketbook!” With this his hand, trembling, goes deep into the bosom of the dead man, and he gives a gasp of joy as it draws forth the black pocketbook of Montez.

Then Wernig mutters: “In other hands, this would have been my ruin! But now!” and the German’s form becomes larger, and his eyes grow luminous with coming potency, as he jeers: “I own the secrets of many Deputies and some Ministers! I will bleed them till they die! I will be rich forever. I hold the politics—perhaps the destinies—of France!”

Then he cautiously leaves the room, and none see him come down the stairs.

The next morning it is reported that Montez of Panama must have committed suicide—though it is hinted to the police not to make too thorough an investigation of the affair—some of the powers that be seeming to fear Baron Montez, dead as he is, will rise up like Banquo’s ghost.

But Herr Wernig lives on the fat of the land, and bleeds some of the potentates of France, right and left. He spares not Ministers nor Deputies who have been bribed, and would keep on so forever; but one day, years afterward, scandal comes, and investigation follows, and he flies from France, fearing that more than any other country upon earth—the country he has debauched and plundered. For the foreign adventurers who came to Paris, lured by the millions spent or squandered upon the Canal, were the greediest, the most devouring—the Swiss, the German, the man of all nations.

* * *

One afternoon in 1892, in the autumn, there is a great naval parade upon the Hudson River, and the flags of all nations are thrown into the air from vessels belonging to the great countries of the world.

And from a private retreat, situated on the Palisades overlooking the river, kept by a doctor well known for his skill in treating diseases of the mind, a gentleman comes forth onto the lawn. He is very elaborately dressed in the latest fashion, and seems happy, as he should be, for a beautiful woman and handsome man walk by his side, and he calls them sister and brother. He looks over the great river, and jabbers, “Ha!” to the guns.

Then, seeing the flag of France, he cries: “It is the opening of the Panama Canal! Montez was right! My dividends! My dividends!” And gazing over the beautiful Hudson he chuckles: “Mon Dieu! What a glorious canal this is at my feet! What dividends we’ll make! Hurrah for De Lesseps, Franc̗ois Leroy Larchmont, and Baron Montez of Panama and Paris!”

Notes and References

- modiste: a fashionable milliner or dressmaker

- comme il faut: behaving or dressing in the right way in public according to formal rules of social behaviour

- Lucullus: Lucius Licinius (ˈluːsɪəs lɪˈsɪnɪəs). 110–56 BC, Roman general and consul, famous for his luxurious banquets.

- petit souper: French – a little supper

- Banquo’s ghost: Shakespear’s Macbeth Act 3, Scene 4: During a banquet, Macbeth is horrified to see the ghost of Banquo sitting in his place at the table.

Parker, M. Hell’s Gorge: The Battle to Build the Panama Canal (London: Arrow Books, 2008).

This edition © 2021 Furin Chime, Brian Armour