Strange, that Electra’s beloved should say of Thorbrand that he may be “evil” but not “dreadful“, and that he would “never take a penny from a man he knew to be poor”. A German Robin Hood? Some say that the before-mentioned Eppelein von Gailingen was one; however, there is little remaining evidence of this.

Robber knights often had no choice other than to take money and riches any way they could. As opposed to today, when many impoverished castle owners open bed and breakfasts or rent out their great halls for wedding parties, these opportunities for income did not exist in the Middle Ages. So there you were, the heir to a crumbling castle, people depending on your income, a few serfs tilling soil for which they offer some of their produce to the owner. Should you take something like an unofficial tax from those rich merchants who wear grooves into the paths through your land with their heavy carts, so you can make ends meet? Many did just that.

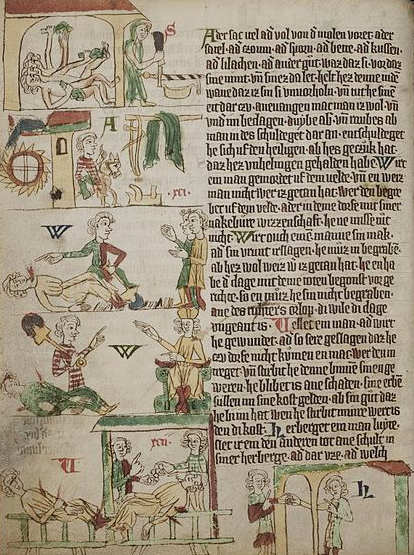

The kings, dukes and so on did much the same, only on a grander scale. Even in the 1700s, they often demanded and went to war over ownership of assets like mines, silver or salt, etc, whether their families had ever had anything to with establishing them or not. Wasn’t that also theft? What then was legal, and what wasn’t? The only written laws appeared from 1220 to about 1235, such as the Sachsenspiegel, which remained a valid legal source in Germany until about 1900. Only seven copies of this German law book remain, all illuminated manuscripts and written in Low German.

It’s called Saxenspiegel (“Saxon Mirror”) because it was supposed to reflect the customary laws of the time. Of course people back then were obsessed with accusing others of witchcraft, or whatever constituted lewd behaviour in their opinions. Women could inherit, but if they married, all their possessions would become property of the male.

Best be careful whom you might be forced to marry then. What will become of Electra if she marries her betrothed? According to the Sachsenspiegel, translated from Low German to High German, “Wenn ein Mann Eine Frau heiratet, so nimmt er all ihr Gut in sein Gewaehre zu rechter Vormundschaft” (“When a man marries a woman, he is granted all her possessions into proper trusteeship as her legal guardian”. (Because women were seen as “incapable of acting legally”, unless they happened to be queens or duchesses.) Can she really trust her suitor?

CHAPTER 3

A FUNERAL — A NEW ARRIVAL

As our heroine approached the castle, she saw through the gathering gloom, the figure of a man — a man who appeared to be looking towards her — standing upon the drawbridge. The gleesome cry of her dog told her that he was a friend, and very shortly thereafter she was leaning upon the arm of her dear lover, Ernest von Linden, who had come out to meet her. He was a young man of four-and-twenty; tall and comely; with a frame of wonderful powers of endurance, lithe and sinewy; his face the mirror of truth and sincerity; his hair of a glossy brown, flowing over his well-shaped head in beautiful wavelets; his eyes of a rich gray, beaming with wit and intelligence; a man, take him all in all, as handsome as you will find in a day’s journeying through a populous district. He wore a doublet of dark green velvet, a white ostrich feather drooped over his velvet cap. and upon his hip he wore a good sword. He was a soldier, every inch of him, holding a captain’s commission from the baroness, and in command, under Sir Arthur, of the forces of the castle, and the town.

“Darling, we had begun to worry about you, and I should have started out to meet you a long time ago, had not Sir Arthur — dear old man! — been taken with an ill turn. So ill was he that I dared not leave him.”

“He is not dangerously ill? Do not tell me that!” cried Electra, in alarm.

“We shall know very soon. Roland has gone on swift horse for the doctor, and it is time now that he had returned. However, there may be nothing to alarm us. He has had just such turns before.”

“Yes,” said the loving niece, with infinite tenderness and pathos in her tone, “but they are worse and worse with every repetition. Dear old Sir Arthur! I hope God will spare him to us a little longer.”

With this they turned to enter the main court of the castle and as they crossed the draw-bridge, Electra saw that the heavy chains were cast loose, and that the windlass of the portcullis was in readiness for use.

“Ah!” said Ernest, in answer to her silent question. “We are making ready to close our gates. It was your mother’s desire and your uncle thought it had better be done. I suppose there can be no doubt that the noted robber chief, Thorbrand, is somewhere in the vicinity. He is no respecter of private property, and if he is accompanied by a sufficient force, he is as liable to strike at a strong castle as at a solitary wayfarer. However, he will find Deckendorf Castle a dangerous place to trifle with.”

“Ernest, what sort of a man is this Thorbrand? Is he as dreadful as people say?”

“If you mean to ask if he is powerful or evil, I should answer you, yes, most emphatically; but if you mean by ‘dreadful,’ is he a bloodthirsty, cruel monster, I should say, no. He never robbed a peasant’s cot, nor took a penny from a man whom he knew to be poor. Further he has been known — so I have been told — to shoot down one of his own men for offering gross insult to a peasant’s daughter; but, alas! that does not hold good, I fear, with regard to wives and daughters of castles. The man is governed by policy. While he can keep the friendship of the peasantry he finds many avenues of safety which he could not find otherwise. He has sacked whole villages, and I have no doubt but that he would attack and rob our peaceful hamlet should it come in his way. He is dangerous man, and he will be a public benefactor who shall slay him or deliver him up to justice.”

They had now entered the broad court, and for a little time they walked on in silence. At length the young captain looked down into his companion’s face, which he could just distinguish in the deepening gloom and asked:

“What are you thinking of, my sweet one? Has my picture of Thorbrand frightened you?”

“No, Ernest, it was not that. A curious thought came to me, and I was trying to see through it. I was thinking: Suppose you and I were walking as we are walking now, only away in the deep forest, and should come upon a man suffering most cruelly — let us suppose him to have been wounded nigh unto death — and we should find him just when a helping, friendly hand could save his life. What should we do?”

“Electra!”

“Pshaw! You don’t think I am going to lead you to such an adventure, do you? Certainly not. It was only a fancy that struck me; and you will see what I mean pretty soon. What should we do to that man?”

“Do? Why, we should put forth every effort to save him, of course.”

“Certainly. And now suppose one thing further: Suppose after we had got the poor man up, and he had blessed us for our kindness, we should accidentally discover that we had saved the life of the Robber Chief, Thorbrand — should we seek to undo what we had done?”

“What a question!”

“Well — but — suppose we had known he was Thorbrand before we gave him help — when we first found his life running away through cruel wounds — would we have saved him all the same?”

“Certainly. I would do so much for the bitterest enemy had in the world.”

“Noble heart! I knew you would. And now answer me this: You have given the robber chief back his life, and he has asked God to bless you for your goodness; and then, after that, when he is at your mercy, are you going swiftly to the nearest barracks to call forth a host to go to the robber’s capture? That is the thought that has been puzzling me.”

“Well, I wouldn’t let it puzzle you any more.”

“I don’t want it to, my dear Ernest, and for that very reason I want you to tell me what you would do under such circumstances.”

“Why, I should do as near right as I could, of course.”

“Would you betray the man whose life you had so kindly saved to a death a thousand times more dreadful than that from which you had secured him?”

“That is a hard question, Electra.”

“I know it; and that is the very reason why I wish you to answer it.”

“Well,” said the youth, after a little thought, stopping at the foot of the steps ending up to the vestibule, “if I must answer your question, I shall have to confess that, under the circumstances which you have supposed, I should not forsake the man in his great need. Betray him, I could not. The man whom I had befriended I could not, in that same hour, surrender to his enemies, let him be saint or sinner.”

“O! I knew your heart would not let you do such a thing.”

“But, tell me, what put that thought into your head? Electra! Have you —”

“Hark! 0! there is dear mamma! Pooh! don’t you go to fancying that I have been doing any such wonderful things. I was thinking, that was all. You know what curious fancies sometimes possess me. — Here I am, mamma! — safe and well, with Ernest and my good Fritz for my guards.”

With that she ran up the steps and threw her arms around the neck of her dear mother, who stood in the heavily arched doorway waiting for her.

“Mamma! Mamma! How is Uncle Arthur?”

“We shall know very soon, my child; for here comes the doctor.”

Electra turned, and saw Doctor Ritter just coming through the inner gateway, with Roland in company. He was a small man, physically; but professionally he was a host. He was, in truth, a physician and surgeon of surpassing knowledge and skill; and had he not owed fealty to Deckendorf — had he not been under a promise to the last baron that he would never, willingly, forsake his old post while the Baroness Bertha lived, he might have found a more profitable location long ago.

The Baroness Bertha von Deckendorf was of the same complexion as her daughter, but not quite so tall. She was really a short woman, and inclined to a healthful embonpoint; and though only forty years of age, the sorrow of. her great bereavement had drawn many lines of silver in her dark brown hair.

“Electra, why did you stay so late? We had become really alarmed.”

“Did you think I might have fallen in with the robber chieftain?”

“Do not make light of that subject, my child. We have positive assurance that the dreadful man is somewhere in this neighborhood; and you know very well what his reputation is.”‘

“My darling mamma, I did not think of making light of it, I assure you. Still I have no fear. But I am safe and well, as you see.”

“For which blessing I thank Heaven devoutly,” murmured the baroness, seemingly to herself, after which she walked on with bowed head, busy with her own thoughts.

In one of the older apartments of the castle, on the second floor, the narrow loopholes of which had been enlarged and glazed, the walls covered with arms and armour of every known description, together with trophies of the chase, lay the old knight Sir Arthur von Morin, now in his seventy-sixth year. His plentiful hair was as white, almost, as the covering of the pillow over which it floated in sinuous masses; his brow was high and full; his face of a leonine cast his frame massive, though now shrunken and shattered. For ten years, since the last going forth of the Baron Gregory, Sir Arthur had been sole master of the castle, and in that time he had endeared himself to, all with whom he had been brought in contact.

But his days, alas! were numbered. Paralysis had followed a severe cold, taken after long and severe exposure in the mountains — a paralysis which had not marred the face, but which had been creeping nearer and nearer to the heart.

Electra, when she entered the chamber, in company with her mother and Ernest, moved quickly to his bedside, and bent over and imprinted a kiss upon his brow.

“Dear, dear uncle! You did not think I had forsaken you.”

“No, sweet one. Kiss me again. Darling, you have been, very precious to me. No, no — I did not think you had run away; yet I wanted to see you — Bertha!” looking toward the baroness, “have you told her of the arrival from Baden Baden?”

“No, dear uncle — I have had no opportunity.”

“What is it? Who has arrived?” the girl asked eagerly.

“It is not a person, my child — only a letter; but a letter of vast moment. It was for me,” said the old knight, “so I will explain it. A letter from the grand duke, informing me that Sir Pascal Dunwolf will soon arrive at the castle to confer with me. He had been informed of my sickness, and is pleased to add that, if it should come to pass that I be utterly incapacitated for military command, Sir Pascal will come clothed with authority to take my place, and — and —”

“What more uncle? Do not fear to speak.”

“Ah! Leopold does not know — he cannot know — what the situation is here. In fact, the letter itself shows that he has been misinformed. Tell me Electra — did Dunwolf ever hint to you of his love? Did he ever intimate to you that he would be happy in the possession of your hand?”

“He! — Dunwolf! — hint to me of love! Merciful Heaven! — he dared not. Has he intimated such a thing? Does the grand Duke write to that effect?”

“The duke writes as though he really hoped you would be happy with Sir Pascal. He says he owes the knight a heavy debt and he can think of no better way in which to pay it.”

“The price he will pay,” said Electra with scornful bitterness, “is my castle and my hand! I wonder if he means to include my soul in the transfer”

“The grand duke must be seen,” suggested the baroness, with calm decision. “Ernest, you are known to him.”

“No, mother. I was well known to his father. During my stay at the ducal court Leopold was absent at the court of the emperor; and since his accession to the throne I have not been at the capital. Still, I will see him? He is reported to be a just and honourable man; and if he be that I have no fear of the result. If, after I have told him my story, as I feel I shall be able to tell it, he can turn a deaf ear to my entreaty I — shall think him neither just nor honourable.”

The entrance of the doctor put a stop to further conversation on the subject of the grand duke’s letter, and attention was now given to Sir Arthur.

At the end of a long and critical examination Dr. Ritter took a seat at the bedside, with one of the patient’s hands in his grasp.

“Sir Arthur,” said he, in a frank, friendly manner, “I know you wish for the truth — the whole of it. — Certainly. Well, I have only this to say: — Put your house in order at once, after which you may quietly await the end. When it will be no man can tell. You may live for days — perhaps weeks; but, I think, not many days, if many hours. I will do what I can for you and, further, I will remain for a time with you.”

After this the doctor prepared the simple medicines he intended to give, and took up his watch with his patient. He had explained to the baroness that the old man was liable to be taken away at any moment, and that the end might come with but little warning. He would let them know if he should detect any change for the worse.

The evening meal was prepared, and after it had been disposed of Ernest and Electra repaired to the apartment of the baroness, where the subject of the grand duke’s project was further discussed; the conference ending with the promise that the young captain would see Leopold, and tell him the story as it was — how the Baron Gregory had planned to dispose of his daughter’s hand, and how such had been the heart’s desire of all concerned ever since, — and then he would respectfully demand that the wishes of the mother and child should be duly considered; and there was no doubt in their minds that justice would be done.

After this Ernest went out to look to the defences of the castle, while the Baroness and Electra repaired once more to the chamber of Sir Arthur, where they found both the patient and the doctor buried in peaceful slumber; and they did not disturb them.

Early on the morning of the following day the baroness and her daughter, who occupied apartments of the same suite, met in the passage leading to the chamber of Sir Arthur. They had but just arisen, and neither of them had yet heard from the sick one. At the old knight’s door the baroness gently knocked, and it was quickly opened by Ernest von Linden, whose cheeks were wet with tears.

No need was there to ask what had happened. Mother and daughter entered the chamber, and stood by the bedside, looking down upon the face of the dead. The good old man had passed away during the night, the doctor could not say when. He could only tell that the passage must have been peaceful and painless. He had slept lightly; at midnight he had given the patient a draught of cordial, and received in return his blessing. At four o’clock he awakened from a brief slumber, and found him sleeping the sleep that knows no earthly waking.

They knelt in the chamber of death while Lady Bertha offered up a fervent prayer to the Throne of Grace, after which the household servants were notified of the solemn event, and those who desired were permitted to come and gaze upon the still, calm face of him whom, in life, they had so truly and devotedly loved.

Then the death-flag was raised upon the main tower of the castle, and a gun was fired upon the western bastion, towards the settlement.

Sir Arthur von Morin had died on Tuesday morning, and it was arranged that the funeral should take place on Thursday, at noon.

Thursday morning dawned, and at an early hour all was in readiness for the solemn ceremonies. A rich casket had been brought from Zell, and the people had come in from far and near to pay their tribute of respect to the memory of the deceased.

Irene Oberwald came over from her cot in the opposite mountain side; but she was forced to come alone, saving the company of one of her father’s dogs. When asked by the warder, at the gate, where old Martin was, she replied that sickness kept him confined within doors. She did not hesitate to go that far in the way of deceiving, since a good and sufficient excuse of some kind was absolutely necessary, seeing that her father had been one of Sir Arthur’s oldest and dearest friends. In answer to the baroness she was more frank. She said that her father was kept at home in attendance upon a sick guest, — an unfortunate traveller who had received a severe hurt in the forest, and whom he felt called upon to kindly nurse.

“Dear Irene, tell me, how is it with my hero?” eagerly asked Electra, as soon as she could get the hunter’s daughter to herself.

“I have not seen him since you left,” the girl replied; “but papa says he is doing well. He has a powerful frame, and most excellent health, and his recovery is likely to be rapid.”

The last note of the solemn service had sounded; the mortal remains of the brave old knight had been consigned to their resting-place in the vaults beneath the chapel, and most of the people had departed for their homes, when, towards the middle of the afternoon, the warder of the castle, Herbert, came in from his post at the great gate, with the intelligence that a large troop of cavalry was approaching.

Electra, upon the spur of the moment, thought of raising the drawbridge and letting fall the portcullis; but even she, upon more sober thought, was forced to the conclusion that such a course would not be advisable.

Fifteen minutes later the head of the column crossed the drawbridge and entered the court. There were five-and-forty well-armed troopers of the Ducal Guard, with a richly-clad knight in command. When the whole force had entered, it was brought to a proper alignment, after which the knight turned over the command to a subaltern, and turned himself towards the vestibule, an orderly and a herald bearing him company.

As the chieftain slipped from his saddle, and gave his horse to the servant, he displayed a thick-set, powerful frame, rather below the medium stature, but making up in breadth what it lacked in height. He was of dark complexion; his hair and beard as black as the raven’s plumage, with a pair of heavily-arched eyes to match. His features were regular, and by many might certainly have been thought handsome. He was a bold man, and reckless of physical danger, but hardly brave; for true bravery presupposes truth and honor, and these were not the characteristics of the man whose face and figure we are now contemplating.

When he had given his horse to his orderly, he started up the broad steps towards the deep arch of the vestibule, sending his herald on in advance; and shortly thereafter the notes of a brazen trumpet smote the ears of the inmates, and the herald proclaimed:

“SIR PASCAL DUNWOLF!”

Notes and References

- portcullis: Heavy gate, such as a metal grill, that can be lowered vertically to close off a gateway.

- vestibule: “An antechamber, hall, or lobby next to the outer door of a building” (lexico.com).

- embonpoint: The plump or fleshy part of a person’s body, in particular a woman’s bosom. E.g., ‘I have lost my embonpoint, and become quite thin.’ Late 17th century from French en bon point ‘in good condition’ (lexico.com).

- subaltern: Officer below the rank of a captain (lexico.com).

“The Heidelberg Saxon Mirror (Heidelberger Sachsenspiegel)“. Heidelberg University. Jump to page.