Louise Minturn continues to read past entries in her diary, specifically those of nine days previous, detailing her second encounter with Harry Larchmont. As in the first three chapters Gunter uses an historical event on a particular day to background action. At midnight March 11th, a storm known as the Great Blizzard of 1888, or the White Hurricane, descended on New York City. Being within the living memory of his contemporary readership it adds authenticity to the story. No one who lived through the storm would ever forget it.

For the first time the metropolis experienced the effects of an oscillation in the polar vortex, which sent a blast of cold air across frozen Canada to meet with a mass of warm air travelling up from the Gulf of Mexico. The previous day had been a moderate 50°F (10°C) with rain in keeping with the close approach of Spring, thus the inhabitants of the city were totally unprepared for what confronted them on the twelfth. Torrential rain had turned to heavy snow, the temperature plunged below zero, snowdrifts reached the second storey of buildings, an estimated 500,000 pounds of horse manure and 60,000 gallons of horse urine froze and along with broken glass and other trash were whipped across the city by 100 mph winds (Mikolay).

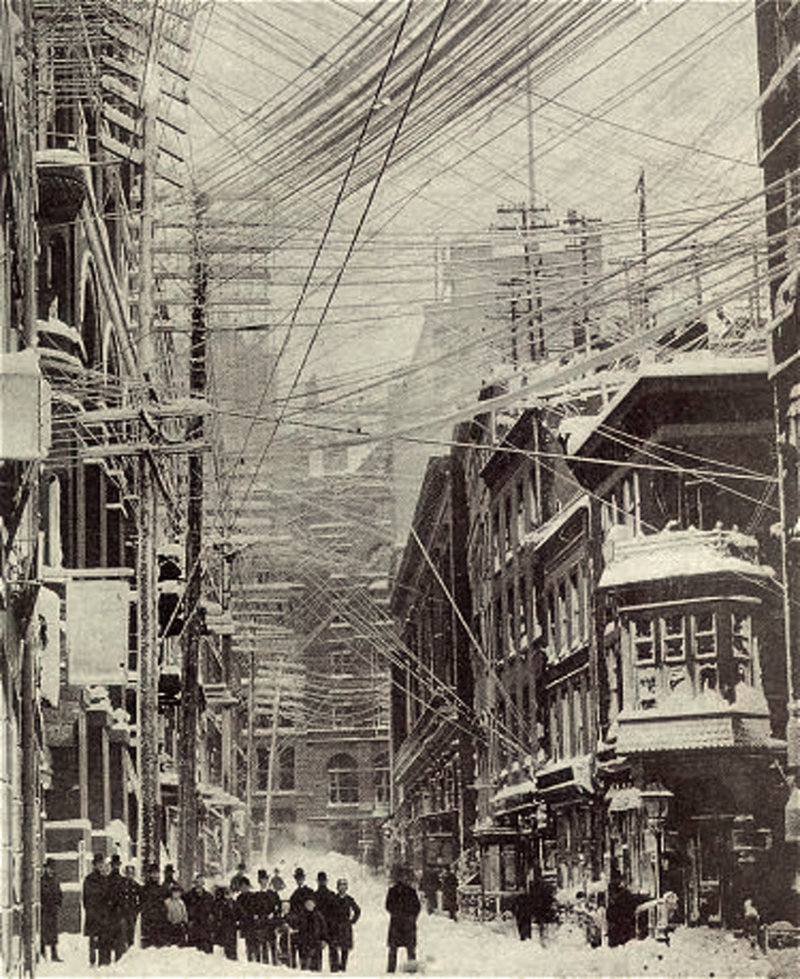

Telegraph, telephone and powerlines came down isolating New York from the rest of the country and live wires buried in the snowdrifts provided a deadly hazard in the streets. Drivers finding the streets impassable unhitched their horses and deserted their carriages, wagons and cars where they stood. Overturned carriages buried in snowdrifts became a feature of the city. Consequently, there were no dairy, bakery, meat or newspaper deliveries upon which the population relied. The elevated rail system froze, trapping thirteen hundred early workers in transit (New York Times).

Mark Twain was trapped in his hotel room while waiting for his wife, Olivia, and sent her a letter (how it was delivered in the conditions is a mystery):

A mere simple request to you to stay at home would have been entirely sufficient; but no, that is not big enough, picturesque enough—a blizzard’s the idea; pour down all the snow in stock, turn loose all the winds, bring a whole continent to a stand-still: that is Providence’s idea of the correct way to trump a person’s trick.

qtd. Clara Clemens, daughter of Mark Twain

As a result of the blizzard two hundred people died in New York City alone (Schulten). The blizzard was an event of great moment not only because of its ferocity and transfixing power, but because it physically resolved arguments for the future development of the city. As early as the thirteenth of March a New York Times journalist reporting on the effects of the storm stated:

Probably if it had not been for the blizzard the people of this city might have gone on for an indefinite time enduring the nuisance of electric wires dangling from poles; of slow trains running on trestlework, and slower cars drawn by horses and making the streets dangerous with their centre-bearing rails. Now, two things are tolerably certain—that a system of really rapid transit which cannot be made inoperative by storms must be straightway devised and as speedily as possible constructed, and that all the electrical wires- telegraph, telephone, fire alarms, and illumination—must be put underground without any delay

New York Times March 13, 1888

In the same article we see the strange beast of American Exceptionalism raise its head in lamentation:

…the most amazing thing to the residents of this great city must be the ease with which the elements were able to overcome the boasted triumph of civilization, particularly in those respects which philosophers and statesmen have contended permanently marked our civilization and distinguished it from the civilizations of the old world—our superior means of intercommunication.

New York Times March 13, 1888

Louise has already ‘broken the ice’ with Harry Larchmont, indirectly through the desperate state of an old man. For the two to meet again in a population of one and a quarter million other chilly New York souls could only be due to the hand of fate. In this chapter, Gunter was perhaps inspired by an actual rescue that occurred during the storm and reported in the New York Times six months later as ‘Romance of the Blizzard’: George Cozine of Hicksville, Long Island was trudging through the snow when he heard the cries of a woman. Buried beneath the snow he discovered Miss Mary McEwen. Finding that her hands, feet and ears were frozen, he dragged her from the snow and throwing her over his back carried her home. `From that time on, he was a welcome guest, and an intimacy sprang up between him and Miss McEwen that terminated in their marriage on Saturday’ (New York Times Sept. 11, 1888). You read correctly, ‘terminated’.

As the proverb goes ,‘’tis an ill wind that blows nobody any good’ and in Louise’s case, despite being someone normally possessed of good sense, her foolhardy actions inevitably place her necessarily in deadly peril.

CHAPTER 9

THE ANGEL OF THE BLIZZARD

Two days after, I received a brief note from Mr. Larchmont, which simply stated he was taking care of his uncle’s minor matters of business, during that gentleman’s recovery, and enclosed to me a check for my services as stenographer, the amount of which, though liberal, was not sufficient to make me think it anything more than a simple business transaction.

Then one week afterwards came the blizzard, that crushed New York with snowflakes, that stopped the elevated railways, and blocked all transportation by surface cars; that confined people in their houses on the great thoroughfares, as completely as if they had been a hundred miles away from other habitations. That dear delightful, fearful blizzard, in which I nearly died.

On Monday morning, March 12th, I am awakened by Miss Broughton, who is peeping out through the casements. She crys: “’Louise, wake up! This is the greatest storm I have ever seen.”

“Nonsense! It’s spring now,” I answer sleepily.

“Yes, March spring!—cold spring! Jump out of bed and see if it’s a spring atmosphere,” returns Sally, with a Castanet accompaniment from her white teeth.

I obey her, and the spring atmosphere arouses me to immediate and vigorous action. In a rush I start the gas stove, and, throwing on a wrap, walk to Sally’s side, and take a look at what is going on in the street.

“Isn’t it a storm!” suggests Miss Broughton enthusiastically. “A beautiful storm! A storm that will stop work. A storm that will give me a lazy day at home!”

“You are not going down to the office?” I say.

“Through those snow banks?” she replies, pointing to six feet of white drift on the opposite side of the street, in which a newsboy has buried himself three times, in an unsuccessful attempt to deliver newspapers at the basement door.

“Certainly,” I reply.

“Impossible!” she says. “You will make a nice, lazy day of it, at home with me. We will do plain sewing. You shall help me make my new dress.” Sally always claims me on lazy days. In my idle moments, I think I have constructed four or five costumes for her. This time I rebel.

“If you are not going to work, I am!” I say decidedly.

“Through those drifts?”

“Certainly!” I reflect that I have some documents Miss Work has promised this day. They are legal ones, and admit of no postponement.

“Well, you may be able to get to the office,” says Sally, “if you are a Norwegian on snowshoes, or an angel on wings.”

This angel idea is a suggestion to me. “The elevated is running!” I answer, and point to the Third Avenue, down which a train is slowly forcing its way. The station is only a short distance from me. I will take the elevated. Surface cars may be blocked, but the elevated goes through the air.

Miss Broughton does not reply to this, though I presume she has her doubts about the feasibility of my plan, for the storm is coming thicker and heavier.

But breakfast over, she steps to the window, looks out, and says disappointedly: “Yes, the Third Avenue trains are still running. I presume you can go, but how about getting back again this evening?”

“Pshaw!” I reply, “it will be all finished in an hour.”

A few minutes afterwards, well equipped for Arctic travelling, I, with a desperate effort, get out of the door, and for a moment am blown away by the wind. I had no idea the storm was so severe. But I struggle on, and finally reach the Third Avenue station, to climb up its icy stairs and be nearly blown from them in my ascent to the platform. From this, I finally struggle on board a downtown train, which contains very few people. The guards have lost their usual peremptory tones. They do not cry out in their bullying manner, “All aboard! Step on lively!” as they are prone to do on finer days, but are trying to get warm over the steam pipes in the car. The blizzard has even crushed them!

We roll off on our journey, amid gusts of wind that nearly blow us off the track, and flurries of snow that make it impossible to see out of the windows. In about quadruple the usual time, however, we creep alongside the City Hall station platform.

It is now half-past nine. I alight, and am practically blown down the stairs, though a snowdrift at the bottom receives me, and makes my fall a soft one. Then I fight my way along Park Place and into Nassau Street. The storm seems to get stronger and fiercer, as I grow more and more feeble. Midway I would turn back, but back is now as great a distance as forward; and one end of the journey means the comfortless railway station, where perchance no trains are leaving now. The other terminus is Miss Work’s office, where there will certainly be a fire, company, and occupation. By the time I shall be ready to go home, the storm must be over.

So I struggle on, and fight my way through snowdrifts, to finally arrive, in an almost exhausted condition, at 1351/2 Nassau Street.

A long climb up the stairs, for the building is not provided with an elevator, and I find myself on the top floor, which is occupied by Miss Work’s establishment. Here, to my astonishment, the door is still locked. Having a pass key, I discover a moment after entering, to my consternation, an empty room, and a cold one. Miss Work, who is punctuality itself, is not here. I reflect, she will undoubtedly arrive in a few minutes. She must come.

While thinking this, for the atmosphere does not permit of delay, I am hurriedly making a fire in the grate, which has not been attended to overnight, the man in charge of the building apparently not having visited it this morning. Fortunately there is plenty of fuel, and I soon have a roaring fire and comfort.

Then I move my typewriter where I get the full benefit of the cheery blaze, and sit down to my work.

Time flies. No one comes. Having nothing to eat, I pass what should be my lunch hour over the keyboard of my Remington, thinking I will have my task finished and go home the earlier. But the papers are long ones, and being legal, require considerable care and accuracy, and as I finish the last of them I look up.

It is nearly dark. My watch says it is only three o’clock, but the storm, which seems to be even heavier than in the morning, causes early gloom. I look out on the wild prospect. As well as I can determine, in the uncertain light, glancing through flurries of snow, not one person passes along sidewalks that are usually crowded with humanity.

What am I to do? I am hungry! I am alone! Even in this great building I am the only one, for no sound comes to me from the offices down stairs, that at this time in the day are usually filled by movement, hurry, and activity.

Sally will be anxious for me. Though, did not my appetite drive me forth, I believe I should attempt to make a night of it in the great deserted building. I should probably be frightened, though I should barricade myself in. I should probably see ghosts of lawyers and legal luminaries who have long since departed, from these their old offices, to plead their own cases before the Court of Highest Appeal. But hunger! I am more afraid of hunger than of ghosts. Besides, it is so lonely.

I decide to force my path to Broadway. On that great thoroughfare there must be some one! I lock the door, come down the stairs, step out on the street, and give a shiver. During the day it has grown much colder, though in the warm room I had not noticed it.

My first step is into an immense snowdrift. Through this I struggle, and reaching the corner of the street am literally blown off my feet, fortunately towards Broadway. Thank Heaven! it is a very short block, though it seems to me an eternity before I reach the thoroughfare that yesterday was the great artery of traffic in New York, but now, as I gaze up and down it, seeking some human face, seems as deserted as a Siberian steppe.

The shops are all closed, even the drug stores. There are no passing vehicles, no struggling pedestrians. The traffic of the great city has been annihilated by this prodigious storm. Telegraph wires, that last night were overhead, have many of them fallen. There is nothing for me but to struggle onward.

I turn my face to the north—up town—where three miles away Sally is waiting for me, with a warm fire, and I hope a comfortable meal. Towards this I force my way—for a few minutes.

Then I trip over a broken telegraph wire that lies in the snow. As I stagger up again, for a moment I am not certain which way I am going. Good Heavens! if I should turn back on my tracks?

The wild snowstorm about me dazes me, confuses me, benumbs me, and makes me stupid. The strength of the wind forces me to hold my head down; I try to see which way I have come by my tracks in the snow—but there are none! The gusts are so violent, my footsteps have been obliterated almost as I made them.

Desperate, I look around me, and see, through snow flurries, the light in the great tower of the Western Union Telegraph Building. It seems awfully far away, but gives me my direction; and I struggle northward once more, staggering through drifts—sometimes falling into them, no voice coming to me—alone in a living city that is now dead—killed by the snow. Darkness has fallen upon the streets, and enshrouds me. Still I fight on. There are hotels farther up the street. If I could get to one—if I could get anywhere to be warm!

I have passed the Western Union Building, I think—I am not sure—my faculties are too benumbed for certainty. All I know is, that I am cold— that I am benumbed—that I am hungry—that I am weak—that the snowdrifts grow larger—the snow flurries stronger—the piercing cutting wind more fierce and merciless—and, above all this, that I am unutterably sleepy. I dream even as I struggle, and then I cease to struggle, and only dream—beautiful dreams—dreams of what I long for—dreams of warmth and comfort, of bounteous meals and generous wine.

And even as this last comes to me, something is poured down my throat—something that burns, but vivifies—something that brings my senses to me with sudden shock. I hear, still in a half dreamy way, a voice that seems familiar, say:

“Pat, that is the worst whiskey I have ever tasted; but I think it has done me good, as well as saved this young lady’s life.”

“By me soul, it has saved mine several times today!” is the answer.

Then the other voice, the familiar one, goes on: “Do you think you can get us up town?”

“Faith, I’ve been half an hour coming from the Western Union Building. You may bless God if I make the Astor House alive.”

“Then somewhere, quick! This will keep her warm.”

I feel the burning stuff pour down my throat once more, and give me renewed life and sentiency. Strong arms lift me into a cab, a rug is wrapped around me. I open my eyes. Beside me sits a man, to whom I falter, my teeth still chattering, “I—I was lost in the snow.”

Even as I say this, the familiar voice cries: “Your tones are familiar. Who are you?”

I answer: “Miss Minturn.”

And the voice cries: “Good heavens! Thank God I saw you from my coupe in time!”

And I, still dazed, gasp: “It is Mr. Larchmont, is it not?”

“Yes: don’t exert yourself, you are weak. In a few minutes we will have you at the Astor House, warm and comfortable. Have no fear.”

And somehow or other, his voice revives me more than the whiskey. I am contented—even happy.

But the storm is still upon us; and though there are two strong horses attached to the coupe, fighting for their own lives through the deepening drifts, it is nearly an hour before lights flash on the sidewalk, and I am assisted into warmth and comfort and life once more, in the Astor House parlor.

There I thaw for a few minutes, during which he sits looking at me, though I am dimly conscious he has given some orders. Having entirely regained my senses, I falter: “I must go home! Sally will be anxious about me!”

“Where do you live?” he inquires shortly “Seventeenth Street.”

“Then you could not live to walk home tonight, and no carriage could take you there. There is but one thing for you to do. The housekeeper will be here in a moment. She will take you to a room. Go to bed, and take what I have ordered for you.”

“What is that?”

“More whiskey—but it is exactly what you want. In two hours they will have dried your clothes, and you can come down to dinner with—with me.” His “with me” is rather embarrassed and diffident.

I do not reply, and Mr. Larchmont almost immediately continues: “Or, if you prefer it, the dinner can be sent up to your room.”

I shall feel quite lonely—it will appear ungrateful. “I will be happy to meet you in the dining room,” I answer.

A moment after, everything he has arranged is done. I go with the housekeeper, a kindly woman of large build and comfortable manner, and find myself excellently taken care of.

Two hours afterwards, feeling like a new being, I enter the dining room. It is only half-past seven, and Mr. Harry Larchmont is apparently waiting for me. It is a pleasant, though, perhaps, to me, embarrassing meal. The room is crowded with people that the storm has forced to take refuge in the hotel—Brooklyn men, who cannot get across the East River; Jersey men, who are cut off from home; and downtown brokers, who are un able to reach their uptown residences. The place, in contrast to the dreadful dearth of animal movement in the streets outside, is full of life, bustle, and activity.

“I think I have arranged very well as regards dinner,” remarks Mr. Larchmont. “We’ll have to be contented with condensed milk, but we shall have some Florida strawberries, and Bermuda potatoes and asparagus.” As we sit down, he says suddenly: “Who is Sally?”

“Sally? Ah, you mean Miss Broughton?”

“Yes, the young lady you said would be anxious about you.”

“Oh,” I answer, “Miss Broughton is my chum!” Then we get to chatting together, and I give him a few Sally anecdotes that make him laugh. As the meal goes on I grow more at my ease, and become confidential, and tell him a good deal of my life, my work, and my battle with the world. This seems to interest him, and once, when I am busy with my knife and fork, I catch his eyes resting upon me, and they seem to say: “So young!”

But I won’t have his sympathy; so I make merry over my business struggles, and tell him what a comfortable little home Sally and I have.

Altogether, it is a delightful meal for me, and I am not sorry that Mr. Larchmont lingers over it. He grows slightly confidential himself, over his coffee, explaining to me that he has had some very important telegrams to receive from Paris; that the uptown wires were all down, and he had been so anxious about his cables, that he had contrived to get as far as the main office of the Western Union Company; that he thanks God he succeeded in doing so, though no cablegrams had come to him. “Because,” he concludes, looking at me, “if it had not been for the cables, you might have been still outside in the snow!”

A few minutes after, he startles me by saying, it seems to me with a little sigh, “I must be going!”

“Where—into the storm?” I gasp, amazed.

“Only as far as French’s Hotel, just across in Park Place.”

I know “just across in Park Place” means three long squares—an awful distance, which might kill a strong man in this driving storm.

“You must not go!” I cry.

“Under the circumstances, I must,” he replies, and rises, to cut short remonstrance. Then I go out with him from the dining room into the hall, a blush on my cheeks, but a grateful look in my eyes, for I know it is to save me any embarrassment this night that he will make his desperate journey through snowdrifts and pitiless wind.

We have got to the ladies’ parlor now. He turns and says earnestly, “I have made every arrangement for you, I think, Miss Minturn, not only for this evening, but for tomorrow, in case you should be compelled to remain here. I am more than happy, and bless God that I met you in time.”

And I whisper: “You have been to me the—the angel of the blizzard!”

At which he smiles a little, and his grasp upon my hand tightens as he bids me goodnight.

Then he is gone into the storm.

I go to my room; a fire is burning brightly there. Sleep comes upon me, and happy dreams—dreams in which I make a fool of myself about “the angel of the blizzard.”

The next morning everything has been arranged for me. After a comfortable breakfast, I discover that the storm has ceased, but the streets of New York are still impassable. Then I get a newspaper, and learn that the indefatigable reporters have somehow got information of nearly everything. Glancing over its columns, I give a sigh of relief. In the long list of accidents, escapes, and deaths on that twelfth day of March, 1888, I note that my adventure has not been reported, though I read that French’s Hotel had been so crowded that people had slept upon the billiard tables and floors of that hostelry, and one uptown swell had been obliged to content himself with the bar counter. I guess who the uptown swell was who did this to save me any embarrassment or anxiety, and I bless him!

I bless him again, when, in the afternoon, I find that the streets can with difficulty be navigated, and the porter coming up, informs me that a carriage has been ordered to take me, as soon as possible, to my address in Seventeenth Street.

At home, I am welcomed by Sally, with happy but anxious eyes. She cries: “Oh, Louise! I thought you were dead!”

“Oh, no,” I reply nonchalantly, “I did a day’s work.”

“And then?”

“Then I went to the Aster House.”

“Did you have money enough with you for that? I hear they charged ten dollars a room.”

“That bill is liquidated,” I return in easy prevarication.

“But you had a carriage! I noticed a carriage drive up with you. How will you ever pay the hackman? They charge twenty-five dollars a trip.”

“Never mind my finances. I am home safe once more. And you?” I answer, turning the conversation.

“Oh, I nearly starved! I would have starved entirely, had I not forced my way to the grocery store. I have been living on crackers and cheese, bologna sausage, and tea without milk.”

“I have been enjoying the ‘fat of the land’. You had better have gone down with me, Sally. You would have had a delightful day,” I continue airily to my pretty chum, who looks at me in partial unbelief.

Then the next morning comes a joy—a rapture—a surprise! It is a bunch of violets tied with violet ribbon, with the name of a fashionable florist emblazoned on it, and with it this card:

Fortunately, Sally is out when this arrives, so I avoid explanation. When she comes in, the flowers soon catch her bright eyes. She ejaculates, “Violets! Where did you get violets, Miss Millionnaire?” and smells them to be sure they are genuine—not artificial.

“Why do you call me Miss Millionnaire?”

“Well, no one but a Miss Millionnaire can live at the Astor House during blizzards, and perambulate in carriages at twenty-five dollars a trip, and have great big bunches of violets at a dollar a blossom! Gracious! They must have cost thirty dollars! Every flower on Long Island was destroyed by snow.” Then Sally’s eyes open very wide with inquiry, and she says coaxingly: “Who sent them?”

“Oh,” I reply in easy nonchalance, “I gathered them!”

“Gathered them? Where?” These are screams of unbelief.

“Off the snowdrifts on Sixth Avenue, over which they have placed a sign ‘Keep off the grass!’”

“That means you will not tell me,” says Sally, with a pout.

“Precisely! “

“What makes you fib so much lately? “she mutters disappointedly.

“It is not a fib—that I will not tell you.”

“Very well! I shall inform Mr. Tompkins!” replies Sally spitefully, which threat causes me to burst into hysterical merriment, I am in such good spirits.

I write to him at his address: “I am quite well. I thank you for the violets, but for the rest—thanks are too feeble. I only hope some day the mouse may aid the lion. L. R. M.”

I initial this note.

Somehow I don’t know how to end it. I have grown strangely bashful and diffident lately.

That was only a week ago. Once since then I have seen him at the theatre, in attendance upon ladies, one of the party being Miss Jessie Severn.

As I have looked at him I have noticed that a good deal of the lightness has left his face, and a portion of the laughter has departed from his eyes. Has some cloud come over his life?

As I look over my diary and recall these things, a sudden thought strikes me. I am going away without bidding him good-by. That will be hardly grateful. It is half-past four: he may be walking on Fifth Avenue. It would hardly be wrong to say “farewell” on a crowded street.

Five minutes, and I have flown over to that fashionable promenade, and am strolling up its thronged sidewalk. I am in luck. Near Thirty-first Street I see him stepping out of a fashionable club. But there is another gentleman with him, almost his counterpart save that he is ten years older, and has a foreign and un-American air and style about him. This must be Harry Larchmont’s French brother—the one Mr. Delafield had sneered at.

Of course I cannot speak to him now.

To my passing bow Mr. Larchmont responds with more than politeness. As I pass, I catch four words from the gentleman who is with him. “She is deuced pretty!”

Fortunately I am beyond them; they cannot see my blushes through the back of my head. What would I not give to have heard Harry Larchmont’s reply!

As it is, I shall not even bid him good-by. I return curiously disappointed to our rooms on Seventeenth Street.

References, Links

Clemens, Clara. My Father, Mark Twain (NY: Harper, 1931) p. 54.

‘Great Blizzard of 88 Hits East Coast’. `This Day in History’ – History.com. Jump to article

‘In a Blizzard’s Grasp: The Worst Storm the City has Ever Known’, New York Times, 13 March 1888. PDF.

Mikolay, Anne M. ‘Remembering the Great Blizzard’ The Monmouth Journal, Feb 10, 2011. Jump to Article

Schulten, Katherine.`Romance of the Blizzard’, Learning Network, New York Times. PDF (NY Times article Sept 11, 1888),

New York, NY, Population History.

This edition © 2021 Furin Chime, Brian Armour