An unopened powder canister bearing the stamp “Dupont Rifle Powder, 1852″ embedded in a tree branch is just one of the curious mysteries the reader will confront in this chapter. There are also alligators and snakes—lots of snakes; and as well, young girls smoking cigarettes.

Louise, our courageous heroine, finds her accommodation comfortable in the house of Martinez, the notary. The family warmly welcomes her and she is treated to a tour of Silas Winterburn’s museum of strange artefacts. In the process, the mystery of Mrs. Silas Winterburn’s Christian name is revealed, though another curious mystery concerning her husband’s treasures remains for another day.

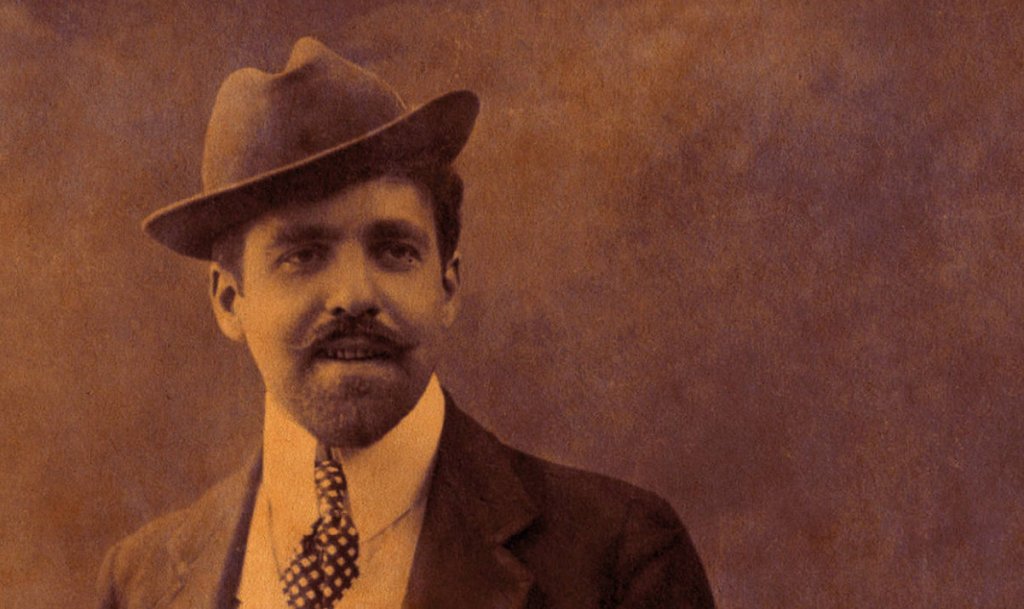

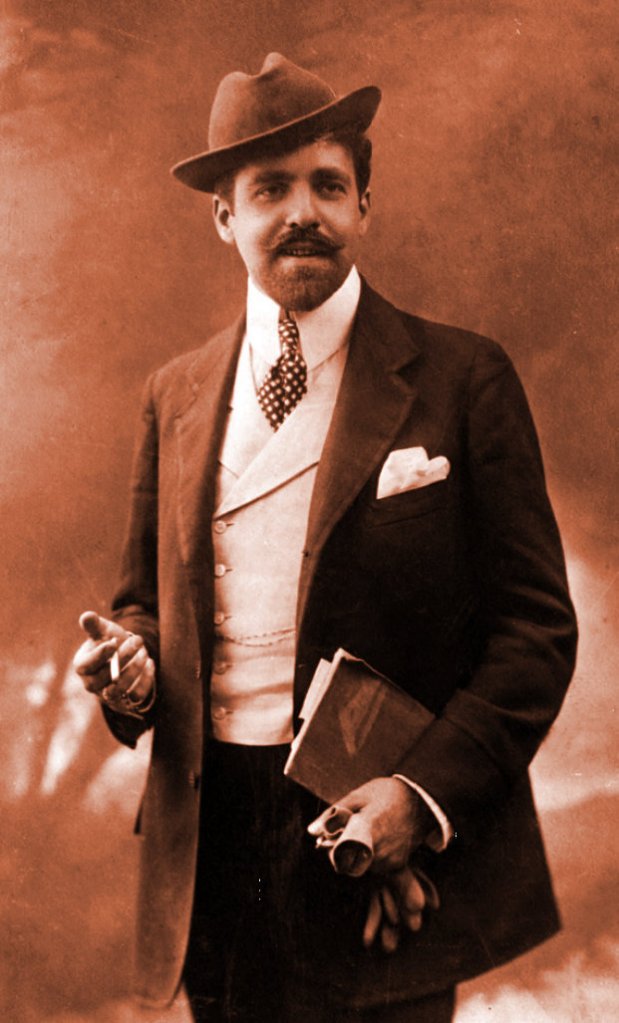

After acquiring his less than salubrious accommodation, Harry’s first act is to purchase a ‘wide-brimmed sombrero de Guayaquil’. While the word ‘sombrero’ may evoke an image of Mexican cowboys and mariachi musicians, it is simply Spanish for ‘hat’. Guayaquil is the largest port and city of Ecuador, and the hat Harry has purchased would have been handwoven by locals from a palm-like plant called Paja Toquilla (or Carludovica Palmata). The sombrero de Guayaquil was popular among workers on the canal. Although made in Ecuador, it is Panama that gives this stylish hat its name, and makes it famous world-wide.

When it comes to his mission, whereas before it was only a suggestion of the narrator, now Harry personally dons the knight’s armour. There is some confusion, however, over which damsel’s colours he bears. He is aware that the only weapons he possesses are his physical presence, good looks and charm; and because of Louise, he feels invested with strong resolve. Previously he has referred to his travel to Panama as a ‘wild goose chase’, and at this point the reader may speculate about what he hopes to achieve.

First through Louise, and now in this chapter, Harry is seeking a means of getting the dirt on Baron Fernando Montez, but to what end? He will be unlikely to discover that Montez is not a Baron. However, if he does find some incriminating or unsavory information about Montez, it is hard to fathom how discrediting the Baron publicly will serve to regain Miss Severn and Frank Larchmont’s fortunes. Of course, possessed of information that Montez does not want made known would give Harry the opportunity to blackmail him, but is that the action we expect of a knight errant?

BOOK 4

THE STRUGGLE IN PANAMA

CHAPTER 15

WINTERBURN’S MUSEUM

Striking a bargain with a mulatto charioteer, half in the English tongue, half in Spanish, Winterburn procures a carriage, and the party take route up the lane leading from the railway station; and passing into the old town of Panama, between houses whose balconies come very close together, they reach the Calle del Cathedral or Main Street.

A moment after, Miss Minturn gives an exclamation of pleasure, for they have come out on the great plaza of the town, and the sunshine is upon it, making it look very bright and pleasant compared to the dark streets through which they have passed.

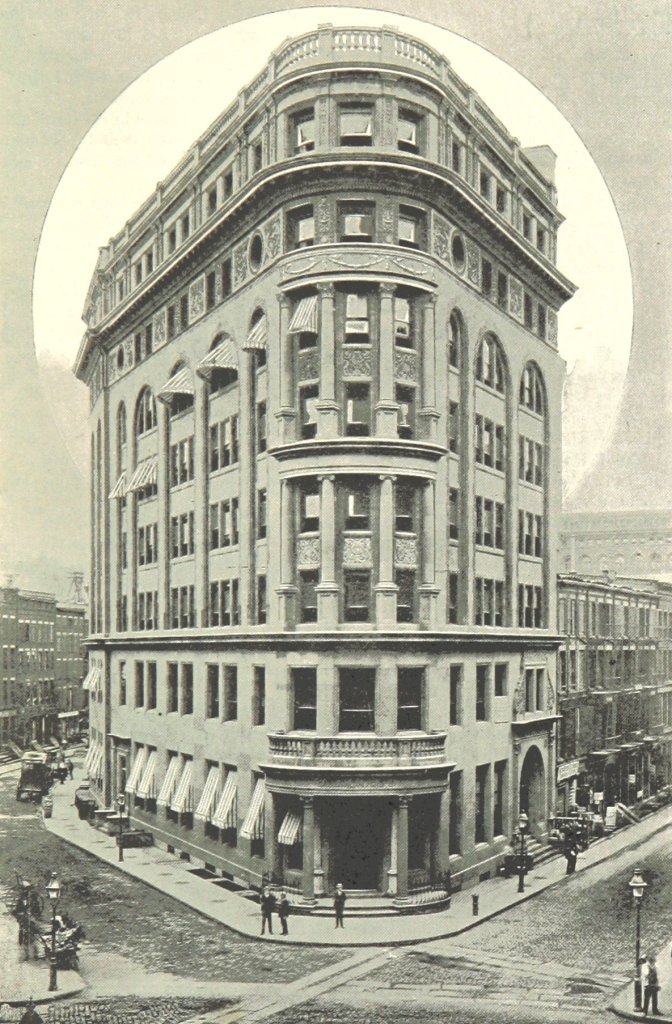

They drive along this, past a little café, with seats and tables on the sidewalk, after the manner of Paris, and then in front of the old Grand Hotel—the one in which Montez had made the acquaintance of the Franco-American. This is now devoted to the offices of the Panama Canal Company—the upper floors being used for business purposes, and the lower one being turned into a general club full of billiard tables for the use of its employees; all lavishly paid for by the money of the stock holders.

Then they come to another café or restaurant, more elaborate than the first, whose tables and chairs are upon the sidewalk like those of the grand Boulevard cafés in far-off Paris. Turning the corner, across the Plaza with its walks and tropic plants, the girl sees the great Cathedral of Panama, old with the dust of centuries. But this is distant and ancient; and the Grand Central Hotel and a lot of offices are near her and modern.

At the old Club International, they turn away from the Plaza and go towards the sea wall and the ‘Battery’; and after passing through more narrow streets with over hanging verandas, they come to the house of the notary, Martinez.

Here Mrs. Winterburn is received in voluble Spanish, by the wife of the official, a Creole lady of about thirty-five, but looking much older, and her numerous progeny; all of them daughters, ranging from twenty-two to fourteen, and all of them, in this rapid sunny part of the world, of marriageable age.

Louise’s Spanish soon makes them her friends, and she finds herself settled very comfortably in a room that looks out over a wide veranda on a little patio, or enclosed courtyard, around which the house is built. This courtyard has a few plants and flowers, in contradistinction to most of the Panama patios, whose inhabitants are too lazy to put into the earth anything that merely beautifies, though the land only requires planting to blossom like Sharon’s Vale. Her apartment is up one flight of stairs, for there are stores underneath, and the family, as in most of the Spanish portions of Panama, live over them.

Inspection discloses to Miss Minturn that she has a clean room, with whitewashed walls and matting upon the floor; a white-sheeted bed, and a few other articles of furniture that are comfortable, though not luxurious. At one end of her room swings a hammock.

“Hammock, or bed! You can take your choice, señorita!” laughs the old Spanish lady. “But if you take my advice, you will choose the hammock—it’s cooler!” and leaves her alone.

Then Louise looking around, finds there is a veranda overhanging the street, to which a door leads directly from her room. With this open there is a very good draught, which is pleasant, as it is now the sultry portion of the afternoon.

Soon her trunk, which has been attended to by kindly old Winterburn, arrives, and the girl unpacking it, makes her preparations for permanent stay, and looking out on the prospect, thinks: “How different this is to Seventeenth Street in New York!” Then she murmurs: “How quiet! and this for a whole year!” and sadness would come upon her; but she remembers there are Anglo Saxon friends in the house with her. She thinks, “Were it not for his thoughtfulness I should be alone and home sick. And I was unkind to him—not because of his proposition, but because”—then cries—“I hate her any way!”

After this spurt of emotion, being tired with the railroad trip, and worried over Mr. Larchmont, Louise thinks she will take, after the manner of the Spanish, a siesta and forget everything; and climbs into her hammock. Being unused to this swinging bedstead, she gives a sudden shriek, for she finds herself grovelling on the floor; the management of this comfort of the tropics not being an accomplishment that is acquired in one siesta.

But the heat will not let her sleep, so she goes into a daydream, from which she is aroused by one of the young ladies of the household coming in, and crying: “Señorita Luisa, I have brought you some cigarettes!”

“For me? I never smoke!” laughs the American girl, partly in dismay, partly in astonishment.

“Not smoke?—and you speak Spanish!” says the Isthmus maiden in supreme surprise. “Let me teach you!”

She lights up, and lolls upon the bedstead, telling the young American lady, to whom she seems to have taken a great fancy, that her name is Isabel, but all who love her call her Belita, giving out incidentally the petite gossip of Panama, between deft puffs of smoke that rise in graceful rings about her.

Louise sits looking at her dreamily, thinking that Panama is a very quaint and quiet place, as it is to her, this afternoon.

Mr. Larchmont’s experiences, however, are different. He drives into the town over much the same road as the Winterburns have taken, but stops at the Grand Hotel, and would engage a suite of apartments of most extraordinary extent and price for a man depending upon the salary of a clerk in the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, or any other clerk for that matter, except, perhaps, some of the Canal Company, who are paid most extravagant prices; but suddenly Harry remembers he is supposed only to have one hundred and fifty dollars a month for his stipend, grows economical, and chooses quarters that do not please him and make him swear—this luxurious young man.

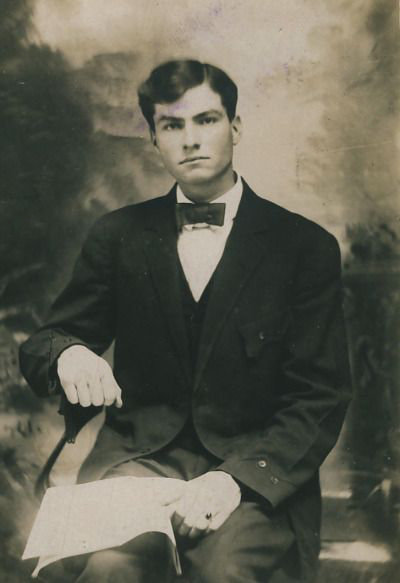

Then having made himself as comfortable as the heat will permit, attired in the whitest linen, and a wide-brimmed sombrero de Guayaquil, which he has purchased in the French bazaar as he drove into town, Harry Larchmont steps out to see the sights of this arena upon which he has come two thousand miles, like a knight of old, to do battle for a young maiden, against the giant who has her in his toils.

Like Amadis de Gaul and Saint George of Merry England, on his journeying he has found another Queen of Beauty to look upon the combat; and though her place is not on the imperial dais, and under its velvet canopy, still one smile from her would make his arm more potent, his sword more trenchant, his charge more irresistible, and nerve him to greater deeds of “daring do,” than those of the maiden for whom he battles, or those of any other maid in Christendom.

So with chivalry in his heart, and a great wish to strike down Baron Montez, the evil champion opposed to him, though scarcely knowing where to find rent in his armor of proof, Sir Harry of Manhattan steps out upon the Plaza de Panama, to see a pretty but curious sight.

A Spanish town turned into a French one!

Not some quaint old village of Brittany, or Normandy, but a bright, dashing, happy-go-lucky, “Mon Dieu!” Cancan, French town! In fact, a little part of gay Paris transferred to the shores of the Pacific. A modern French picture in an old Spanish frame.

As he leaves the hotel, the Café Bethancourt, just across the street, is filling up with young Frenchmen arrayed very much as they would be on the Champs Élysées or Boulevard des Italiens. They have come in, as they would in la belle Paris, to drink their afternoon absinthe.

Open carriages, barouches, landaus, are carrying the magnates of the Canal management, with their wives and their children—or perhaps some one else—about the Plaza preparatory to their drive to the Savanna; which, unheeding the mists of the evening, they will take as they would in the Bois du Boulogne, though the miasma of one breeds death, and the breezes of the other bring life.

All this looks very pretty to the gentleman as he strolls through the Plaza, between green plants and over smooth walks, and notes that about this great square none of the surrounding buildings, save the great Cathedral and the Bishop’s Palace, have now the air of old Spain. The rest have become modern Parisian cafe̕s, offices, hotels, bazaars, or magazins.

After a few moments’ contemplation of this, the young man says to himself: “But I came here for work! To discover the weak spots in this villain’s armor, it is necessary for me to know those who are acquainted with him, those who have business with him; in fact, the world of Panama! And to become acquainted with these novel surroundings, first my letters of introduction.”

So he starts off, and after a few inquiries, finds the office of the American Consul General, which is just opposite the Bishop’s Palace, in the Calle de Comercio.

Fortunately this dignitary is at home, and Harry, presenting his credentials, is most affably received, for his letters bear very strong names both socially and politically, in the United States.

“I’ll put you up at the Club International immediately,” says the official. “There you will meet every body! Supposing you drop in there with me this evening?”

“Delighted!” returns Harry, “provided you will dine with me first—where do they give the best dinners?”

“Oh, Bethancourt’s as good as any.”

“Well, dine with me there, will you? Half-past seven, I suppose’ll be about the hour.”

“With pleasure,” answers the representative of America. And Mr. Larchmont, noting the official has business on his hands, leaves him and saunters off to kill time till the dinner hour, curiously enough asking the way to the house of Martinez the notary, but contenting himself with walking past and giving a searching glance at its windows, though he does not go in.

Then he strolls back to the hotel to dress, and being joined by the consul the two go to the swell café of Panama, where Mr. Larchmont gives the representative of Uncle Sam a dinner that makes him open his eyes and sets him to thinking, “What wondrous clerk has the Pacific Mail Company got, who spends half a month’s salary upon a tête à tête and that to a gentleman? Egad, I’d like to see this young Lucullus entertain ladies!” a wish this gentleman has granted within the next few days, in a manner that makes him and the whole town of Panama open their eyes; for Harry suddenly goes to playing a game at which he cannot be economical.

This comes about in this manner. Larchmont and his new friend are enjoying their coffee, seated at one of the tables outside; scraps of conversation coming to them from surrounding tables. The one next to them is occupied by two excitable and high-voiced Frenchmen, one an habitue of the Isthmus; the other a later arrival.

“I wish,” says the newcomer, “that I could get some definite word out of Aguilla about their contract with me. But he puts me off, saying that Montez when he arrives will attend to it. Now Baron Fernando likes the great Paris better than the little one. He has not been here for a year. I am waiting two months, and I’m rather fatigued!”

“You won’t have to wait much longer,” laughs his companion, the Panama habitue. “Baron Fernando will shortly arrive.”

“Ah, has his partner told you?”

“No, Aguilla never says anything.”

“Then how do you know?”

“How?” says the old resident, with a wisely wicked smile. “By that!” and he points to a placard hanging on a wall nearby. Following his glance Harry Larchmont sees that it announces that Mademoiselle Bébé de Champs Élysées of the Palais Royal, Paris, will shortly make her appearance at the Panama Theatre.

“When Mademoiselle Bébé is announced, Baron Montez very shortly afterwards steps on the stage,” continues the gentleman at the table.

“Ah, she is a friend of his?” queries the other.

“Sans doute! So much of a friend that she never comes here without her cher ami, Baron Montez, arriving very shortly after her.”

“You seem interested in the conversation next us, Larchmont,” whispers the consul. “Do you know the famed Baron Montez?”

“A little!” answers Harry abstractedly, for he has just thought what he thinks a great thought, and is pleased with himself.

It is something after this style: “Perhaps here is a flaw in my enemy’s armor of proof. Perchance Mademoiselle Bébé de Champs Élysées has the confidences of her cher ami my adversary. Mayhap from her I can gain some knowledge that may give me vantage over him! “Then he laughs to himself quite merrily. “By Jove! what great friends Mademoiselle Be̕be̕ and I shall be!”

With this rather unknightly idea in his mind, the young gentleman proceeds to pump the consul and everyone else he meets this evening, about the coming dramatic star at the Panama Theatre, and very shortly discovers that de Champs Élysées is a young lady, who, though she is by no means prominent on the Parisian boards, is considered a great card in Panama.

This has been chiefly owing to the push that has been given to her artistic celebrity by the devotion of Baron Fernando, who has lavished a good deal of money and a good deal of time upon this fair élève of the café’s chantants and the Palais Royal.

After a little, anxious to learn more about her, Harry proposes to his guest that they drop into the theatre. So they saunter to the temple of Thespis where a Spanish opera company that has come up from Peru is giving “High Life in Madrid”, which is so much like high life in Paris embellished by the chachucha and fandango instead of the cancan, that it greatly pleases the mixed French and Spanish audience.

Though everyone else is interested in the performance, Mr. Larchmont is not. He is devoting himself to discovering all about the attraction that is to follow it. Getting acquainted with one of the attachés of the theatre, he learns that Mademoiselle Bébé de Champs Élysées will arrive within a day or two, and appear probably the next Monday. That she is not a very great singer; that she is not a very great actress; that she is not a very great dancer; but that she is “a very diable” as the old door keeper expresses it.

“However, Monsieur is young, handsome, and I hope rich. So he can soon see for himself,” suggests the old man with a French shrug of the shoulders.

The opera over, Harry and the American official go to the Club International, which has been moved from its former quarters on the Grand Plaza, to a house called “The Washington,” somewhat nearer the railroad, and in the old Spanish quarter. Here they find some billiard-playing, some chess, and lots of Frenchmen, Spaniards, and in fact a good deal of the male high life of Panama.

Mr. Larchmont is introduced right and left, and being anxious to make friends, soon has lots of acquaintances, for his offhand manner wins everybody. All that he learns here, using both tongue and ears with all their might, satisfies him on one point, and that is, that Mademoiselle Bébé de Champs Élysées will know the secret thoughts of Baron Fernando Montez, if any one does.

So he chuckles to himself: “I’ll nail this scoundrel Samson of Panama by this naughty Delilah of Paris!” and considers himself a very great diplomat, and a wonderful cardplayer in the game of life, as he goes to bed about three o’clock in the morning, which is a rather bad time for an industrious clerk to retire to rest, if he wishes to be at his duties in the Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s offices early the next morning.

But even as Harry turns into bed, he mutters: “If she had been kinder, I should not have done this thing!”

Still, notwithstanding his buoyant nature that considers half the battle won, this young gentleman, as he closes his eyes, gives half a sigh, and wonders what has been lacking in his life this day; then suddenly becomes wide awake, as he mutters: “By Jove! I have not seen her face—I have not looked into her eyes—or heard her voice for twenty-four hours!”

Next grows angry and indignant and cries out: “Hang it! I will go to sleep. No woman shall keep me awake!”

But notwithstanding this determination, he tosses about on a sleepless bed for an hour or two, and wonders if it is the mosquitoes of Little Paris.

As for the object of his thoughts, she has passed a quiet evening with the Winterburns, and the family of old Martinez, who has lived a long time upon the Isthmus, and tells her anecdotes of the earlier days of Panama, before it became, as he calls it, “a French colony”.

Some of his daughters are musical, and Louise and they sing snatches of the old operas together, in duos, trios, and quartettes, to the accompaniment of mandolin and guitar; music which seems in keeping with the tropic evening and quiet of this Spanish portion of Panama, which is half deserted after nightfall.

Winterburn breaks in after each selection with a quaint mixture of American applause and Spanish bravos, sometimes saying with a sigh: “Tomorrow I’ll have to be going off to work on my Chagres dredger again at Bohio Soldado.”

‘“You have lived on the Isthmus a long time,” remarks Miss Louise. “I suppose now you’re used to it.”

“Well, yes, pretty well. I’ve been on it so long that I know everything about it.”

Then he astonishes the girl, by ejaculating suddenly: “Would you like to see my museum?”

“Your what?” asks Louise.

“My collection of curiosities. I’ve got most enough to run a dime show, in the U. S. Just let me add a couple of San Blas Indians, a live crocodile, an anaconda, and throw in a Spanish dancing girl, and the pen with which De Lesseps signs Panama bonds, and diablo! I will do a fine business on the Bowery!”

“The Bowery!” says his wife. “Why, Silas, have you ever seen the Bowery?”

“Yes, I saw it on my third wedding tour, ten years ago,” he remarks contemplatively. “Sally—she was the one before you—was very much taken with it also. I’ll give you a show at it, too, Susie, some day.”

On this cheering remark Miss Minturn breaks in, saying: “The museum, quick!”

“Then I’ll accommodate!” replies Silas genially. “I always like to accommodate pretty girls, even when they’re thick as candles in a cathedral, as they are about here,” and he looks around at the various señoritas of the Martinez family, with a jovial chuckle, and a horrible soto voce remark: “Perhaps some day, if I live long enough, I’ll be marryin’ one of ye.”

So they all troop into a big room at the end of the house, which had once been occupied by domestic impedimenta of the Martinez family that are now crowded out by the collection of this pioneer of the Isthmus.

It is a conglomeration of odds and ends picked up in nearly forty years of the Tropics. This he proceeds to walk around, giving a lecture very much after the manner of exhibitors of similar collections in the United States.

“Here,” he says, “ladies and gentlemen, is the first spike that was ever driven in the Panama Railroad. I know it’s genuine, for I pried it out and stole it myself.

“This,” he shouts, pointing to a hideous saurian of tremendous size, “is an alligator I killed myself down on the Mindee in ’55. There were lots of them there in those days—big fellers! This chap is reported to have eaten a native child, but I don’t guarantee that!

“Here,” and he points to some curious images, “are some of the old statues taken from Chiriqui temples. Dug ‘em up myself, and can swear to their bein’ the real genuine. Archaeologists declare that they take us back as far as the times of most ancient record, equivalent to days of Pharo’s Egypt.

“Lot number four is a bottle of snakes of my own killin’ also. The one with the big head is what the natives call the Mapana down on the Atrato, whose bite is certain death. Here is a Coral, likewise deadly. Killed it in the ruins of old Panama. And that reminds me—by-the-by, Miss Louise, I want to give you a little advice about snakes in this country. Most people will tell you there ain’t none about here. So there ain’t, in town here, and along the works of the Panama Canal and Railroad. But I remember in the days in old Gargona, when the passengers went down from the board hotel to take boat for Cruces early in the morning, and a negro boy always went ahead, swinging a lantern, to scare the creepers away. When you go into the country, you wear high boots, and don’t skip around old trees in openwork stockings!

“Here is a counacouchi,” and he points to a stuffed snake some thirteen feet long. “The natives here call it a name I can’t pronounce, but it is the same as frightens people in Guiana under the high title of ‘Bushmaster’. It is the deadliest and fiercest viper on earth. He don’t wait for you to come at him—he comes at you. Look at them inch and a half fangs! There’s hyperdermics for ye!” And he shows the two fangs of that deadly snake, some of which inhabit the more inaccessible parts of this Isthmus of Panama, together with the no less dreaded lance-headed viper—the Isthmus prototype of the hideous Fer de lance of Martinique, and Labarri of Guiana, scale for scale, the only difference being that climatic changes have given different coloring to the snake.

“Oh, no more of this,” shudders Louise. “I shall dream of snakes!” and turns away to examine a hideous idol.

While doing this, she cries suddenly: “What is this?” and points to the branch of a large tree, in whose solid wood is imbedded a powder canister, which bears the stamp “Dupont Rifle Powder, 1852,” though age has rendered it scarcely legible.

“The first,” says Silas, “is an idol that the Indians used to worship before the Spaniards taught ‘em better. The second is a proof of the wonderful growth of all vegetable substances in this rapid land. I was working my dredger on the main Chagres last rainy season. It was just after a flood, and there was a pile of brushwood coming down the river, when I seed somethin’ glisten in the floatin’ rubbish, as it went past me, and fished this out, and brought it over here. That tree must have been growin’ around that old Dupont powder canister that probably some California miner flung away, for perhaps thirty odd years, and has now become part of it.

“Well! you have not much curiosity, though you are a Yankee!” laughs Louise.

“Why?”

“Because you have never removed the lead stopper from it. There might be something inside.”

“Oh, open it, Silas!” cries his wife. “Perhaps there’s money in it!”

“Oh, leave that for a rainy day. Ye can spend an afternoon investigating it, when I’m on the dredger. At present I am goin’ on with the museum: Lot number six. Bow and poisoned arrows. Have been used by the San Blas Injuns in fighting off surveyors and explorers. The high mountainous nature of the country prevents their bein’ conquered, and at present they are the only politically free people in the State of Panama!”

“Hush!” cries the old notary, laughing. “Don’t touch on politics, my friend Winterburn.”

“Oh, ho! Is there another revolution on foot?” inquires the Yankee, and goes on with the description of his collection.

Some of his curiosities are very peculiar, notably an idol with revolving eyes.

After a time, Miss Louise grows tired of idols, bows and arrows, snakes, lizards, and jaguars, and suggests that they leave the balance of the curiosities for another day, as she is anxious to be at her post early in the morning.

Alone in her room, Silas’ warning about snakes impresses her so much that she climbs into her hammock, thinking with a shudder that it is safer than the bed. But she can’t sleep in the hammock and crawls timidly to the bed, and there forgets about snakes, for her pretty lips murmur—“Harry” as unconsciousness comes over her and closes her bright eyes.

Notes and References

- Carmelo Fernández watercolor: Fernández worked for the Comisión Corográfica of New Granada (present day Colombia and Panama): “The commission, which began work in 1850, studied the geography, cartography, natural resources, natural history, regional culture, and agriculture of New Granada”. He painted about 30 watercolours for them between 1850-52. Library of Congress, World Digital Library.

- ‘San Blas Indians’: Showing Louis his collection, Silas makes a comment about the ‘Sans Blas Indians’, remarking that they are the only free people in the State of Panama. Sans Blas is a group of three hundred and sixty low-lying islands off the east coast of Panama in the Caribbean Sea. The Guna (Kuna) people who previously lived throughout Columbia and Panama, retreated to the islands to preserve their culture, and to escape other hostile tribes and the mosquitos of the mainland. They maintained their own religion and government, fiercely rejecting attempts to suppress their traditional culture. Following a successful revoltion in 1925, The Guna forged a treaty with Panama to retain their cultural autonomy. Self-governing, the islands are administered as a ‘country within a country’. San Blas province is rich in tradition. The Guna follow their own customs, laws, and legislation, and preserve their natural environment and heritage. See Howe, J. , A People Who Would Not Kneel: Panama, the United States and the San Blas Kuna. (Smithsonian Books 1998).

- Sans doute: French – without a doubt

- cafe chantants: a café where singers or musicians entertain the patrons

- Thespis: Greek poet. First credited with appearing on stage as an actor portraying a character.

- diable: devil

- The Bowery: a street and neighborhood in the southern portion of the New York City borough of Manhattan.

- Chiriqui: Chiriqui Grande in the region of Bocas del Toro is a town located in Panama – some 177 mi or ( 285 km ) West of Panama City.

- Sharon’s Vale: in the Bible it only occurs as the name of two separate regions: one is a pasture land east of the Jordan occupied by the sons of Gad (1 Chronicles 5:16), the other is the plain that covered much of the north coast of Israel (1 Chronicles 27:29).

- Amadis de Gaul: 14th Century Spanish chivalry story series

- Lucullus: Lucullus was a Roman general who is known for his campaigns in Asia Minor against Mithradates, but is even more renowned for the extreme luxury in which he lived, both in camp and at his estate outside Rome. The word “lucullan”, in fact, means extreme opulence. Jump to Reference

Howe, J. A People Who Would Not Kneel: Panama, the United States and the San Blas Kuna ( Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. 1998)

Panama Hat: Historia del panama hat

This edition © 2021 Furin Chime, Brian Armour