In a gradual increase in intensity over the past chapters two relics have been revealed. First the tintype image of Alice Ripley, then the contents of the powder canister: a string of pearls and a note inscribed in blood on a cuff. These have only reinforced Louise’s belief, first raised by Harry, that Montez is responsible for her grandparents’ death. And now the oldest and living relic of the times will tell his tale. He, who was old and in retirement when Montez chanced to recruit him on the beach decades ago, with the promise of banditti work. His reply: ‘Si, Señor, mouches dinero, mouches sangui, mouches Domingo’.

Calling Domingo, which means ‘Sunday’ in Spanish, an ex-pirate is a bit of a stretch as readers know he was only a cabin boy on one of Jean Laffite’s ships. Jean Laffite and his brother, Pierre were not called pirates, but smugglers, buccaneers and privateers, not of the same ilk as Henry Morgan and Blackbeard or other blood-thirsty swashbucklers from an earlier time. On the contrary, though described as ferocious against enemies, Jean Laffite was considered a gentleman, suave, fashionable and highly intelligent (Canwright). After relieving a ship of its loot, whether gold, silver, other goods or slaves, if he could not make use of the vessel, He was known to return a ship to the captain and his crew (Davis, pp. 44-95). Following the purchase of Louisiana by the United States an embargo on the importation goods was put in place in 1807. The Laffite brothers, long-term residents and well connected amongst the plantation owners and merchants of New Orleans, set up a smuggling operation on the island of Barataria. Barataria which lies to the north of New Orleans harbour is connected by a narrow passage navigable only by barge (Ramsay pp. 33,37-39). In due course, they purchased a schooner and outfitted it with guns, eventually commanding a fleet of seven ships. Laffite assisted during the War of Independence by blocking the entrance to the Mississippi River, and participating in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. Andrew Jackson commended him for his ‘courage and fidelity’ (Ramsay pp. 2,14).

Domingo would make an interesting psychological study. Gunter introduced him as ‘a gentleman with a pirate countenance adorned by two fearful scars, with a stalwart black frame, and a stout black heart beating in his black body’. Likely an orphan, perhaps due to diseases such as Yellow Fever or Malaria, he may have fled from the Caribbean Islands to seek safety in Louisiana as many natives did. Left to wander the streets of Panama, eventually falling in with a crew of Laffite’s, perhaps acquiring in the process a father figure, at the very least an acceptable code of conduct: that of taking, rather than earning an existence, which later he would express in banditti work on the Cruces trail with Montez. A big boy, all his insecurities and childhood resentments contained in an intimidating brutal exterior. He now calls himself ‘Domingo of Porto Bello’ perhaps to distinguish himself from other `Domingos’—a last name as it were, or again maybe in Porto Bello he has found a sense of place in this world.

It was Domingo who shot Louise’s grandfather through the temple while he was strangling Montez. In this chapter he appears twice to throw his weight around and make his formidable and terrible presence felt. Louise’s restraint is admirable, she has already sat by the two knowing they killed her grandparents—another might react over-emotionally in the circumstances, but not our Louise—no, she keeps her cool. In this chapter she is tested to the limit.

The leading edge of the narrative stream is the swelling bow wave of the reader’s imagination. Having read the novel up to this point, knowing the characters, at times better than they know themselves, knowing also the issues involved—the plot thus far—knowing all this, in your mind you have formulated probable events to come. The reader is primed to be consoled in their correctness or surprised by a disruption of their speculations.

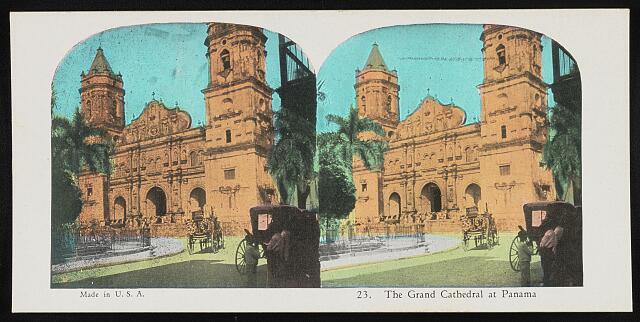

Montez prepares to quit Panama forever and with an endowed prescience predicts the fall of the Panama Canal project and the effect it will have on France. He reveals that he has divested any interest in the Canal Interoceanic company, and dreams a little of a future in the United States.

This reader had been contemplating a solution to the problem of regaining Jessie Severn and Francois Larchmont’s finances. To secure their wealth, which is in Montez’ hands and which he now has placed in US securities, the best thing might be for Jesse to marry Montez. Yet this seems unlikely given the strength of nineteenth-century values and sensibilities, and the fact that Harry, Francois and Jessie, though she has little choice in the matter, are opposed to it. The second part of the plan would involve Fernando’s timely demise, somehow…

However, Gunter does draw special attention to a particular article belonging to Montez, which remarkably so far has escaped notice. In murder mysteries it is considered bad form, unfair to the reader, to introduce a decisive clue right at the end of a train of deductions. It remains to be seen, but given the descriptive treatment it receives, indications are this article may serve a crucial role in saving the day for Jesse and the brothers Larchmont.

CHAPTER 20

DOMINGO OF PORTO BELLO

Now, this absence of the young lady from her office duties she has explained in person to Aguilla, who has said in his kindly way: “That’s right, my dear. If you can save a victim from the fever, do so. There are so many who are not saved,” and gives indefinite leave of absence.

This being reported to Montez, he meditates: “Ah ha! The pretty Louise loves him yet—this Harry Larchmont—though he loves my fiancée in Paris!” Incidentally meeting, that day, the doctor who attends Larchmont, the Baron makes careful inquiries on the plea of being the intimate of Harry’s Parisian brother, and is informed that there is no hope of his recovery.

So he laughs to himself:

“Again I triumph! See how my enemies fall before me! I leave this place clear! Tomorrow I go away from Panama forever! To my wedding day—to enjoy the beauty of Jessie Severn—to be rich as a prince—to be one of the great ones of the earth. I have eaten up everyone; though they do not know it, they are in my jaws now!”

And they are; for he has made such arrangements that none of them will ever see any of the gold of Panama. Domingo’s stock will be lost to him; he will receive his dividends no more. Aguilla, his partner, is ruined, or will be soon after Montez gets to Paris. Wernig, his chum, will have hardly a fighting chance, and Francois Leroy Larchmont no chance at all. Everyone has been eaten up by this Vadalia Cardinalis.

Montez, with his astute mind, has looked over the field. He knows the Canal Company, lottery or no lottery bill, will not last out the year, and with this failure must come such an explosion from French investors, that will upheave even France itself.

Investigation must show jobbery and fraud almost unequalled in the history of the world.

So he has withdrawn himself from the storm, as far as possible. He has made large investments in American securities. These are in the hands of a New York banking house, solid as a rock—one that has little to do with France—one that has never in any way been interested in French securities, or the Canal Interoceanic.

“I can live on that, a Fifth Avenue nabob, in America, if the worst comes to the worst,” he thinks, as he consults the black pocket-book he always carries with him, and which day by day, and night by night, is his own particular care.

So he makes his preparations for departure in very happy mood.

As he is bidding Aguilla goodby, that gentleman says to him nervously: “You are sure the Canal Lottery Bill will pass?”

“Certain as that I stand here!” cries Montez.

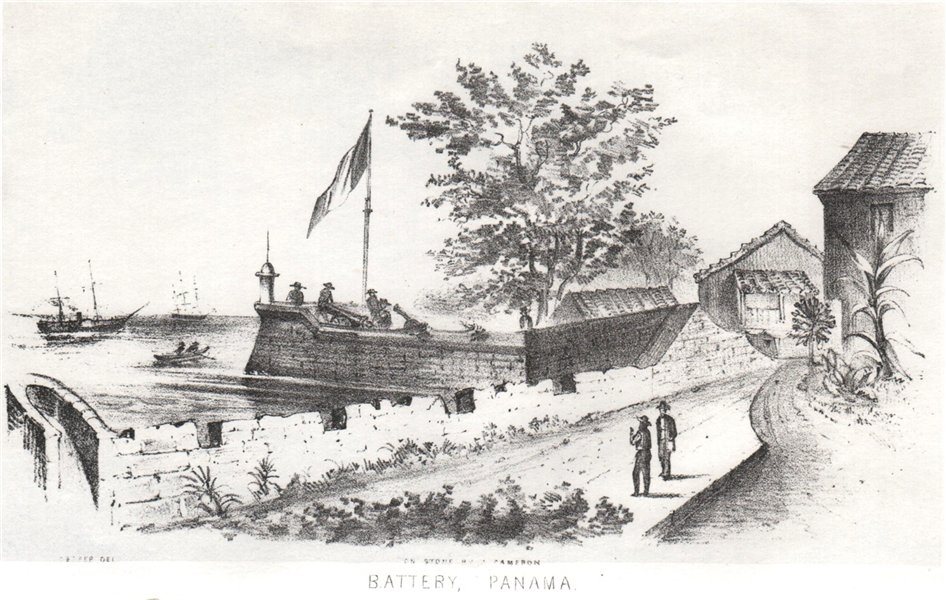

So Fernando goes away from Panama, receiving merry adieux, and passing over the railroad to Colon. At Matachim he looks up the Chagres River towards Cruces, and his eye says: “Adieu forever!”

Taking steamer on the Atlantic side, Baron Fernando Montez goes to New York, where he will spend a fortnight, looking after his American investments, and seeing that they are as certain as securities can be.

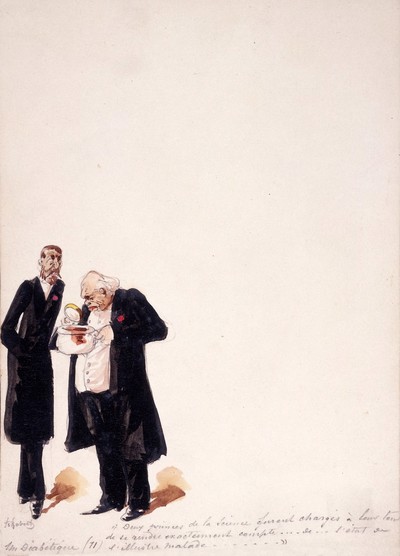

Within a week after he has gone away from Panama, there comes a commotion in the office. He has left certain letters written in his own hand, to be delivered. Bastien Lefort brings in one of these, and mutters in a broken voice: “Where is the Baron Montez? Mon Dieu! I am a ruined man!”

Being informed that the senior partner has gone away, he wrings his hands and interviews the junior.

After reading his letter, Aguilla himself turns pale, and his fat face becomes thinner, and he also gasps: “Mon Dieu!” Then he shuts himself up in his private office, and tears run down his fat face—the bourgeois tears for loss of money—for he moans to himself: “If what this letter tells me is true, Montez has destroyed me also. My God! my children! How can I stop him? What hope is there?”

But into this scene comes a happier face. Louise Minturn, radiant as the sun, though her young face bears lines of care, from ceaseless watching and careful nursing, comes in half crying, half laughing: “Thank God! he is saved! The doctor says he will live! You understand me? I am back for work, Monsieur Aguilla! The doctor says Harry—Mr. Larchmont will live.”

But before Aguilla can answer, there is a harsh voice outside, and a terrible thump on the door, and in strides the black man with the two great red scars and the white wool.

He cries hoarsely: “Where is this ladron—this Montez? I have had his letter read to me. It says my gold is gone. I, Domingo of Porto Bello, will wring his slippery neck!”

“Montez has gone—to—to France!” stammers Aguilla, for the appearance of the ex-pirate frightens him.

“To France!—Thousands of miles from me!—But you his partner are here—in my grasp!” howls Domingo, and seizes poor Aguilla by the throat, growling: “Tell me, liar! Tell me, dog! Tell me, where are my dividends, or I will strangle you!”

Old as Domingo is, Aguilla cannot get away from his grasp, though he contrives to gasp out: “You want—your month’s dividends?”

“Yes! This letter says I shall have none!”

“You shall have them!”

“Now or your life!”

“Certainly! The—the fifty dollars!” stutters Aguilla, and pays it agitatedly out of his pocket; forgetting even receipt for same, though this is not natural to his bourgeois nature.

“Ah, Diablo!” cries Domingo, chinking the silver and gold. “Now for the pirate’s delight—the rumshop!” and goes off, leaving Louise and Aguilla gazing at each other astonished and dismayed.

Then Aguilla says suddenly: “Thank Heaven none of the clerks heard!” and looks into the outer office, which is quiet—the employees are all at their lunch. At this Louise, turning to the Frenchman, queries: “What does this mean?”

“I cannot tell you at present,” he answers. “Come tomorrow!” then looking at her he says consideringly: “I may have a curious mission for you. It will be very important. Come tomorrow for instructions.”

“You do not want me today?”

“No, go back and nurse your sick friend. My little daughter is sick also. I must go to Toboga!”

So Louise, happy to get to the bedside where she has fought death and won, goes back to her vigil beside the couch of Harry Larchmont the American, and beside his bed is a telegram; but the doctor says, “Not yet; he is not strong enough.”

The next day she blesses God again, for he is better, and his brain is clear, but he is weak—so weak; though there is a look in his eyes that indicates he is happy, as she ministers to him with the tender hand of loving woman: the tender hand that comes to men in sickness: the tender hand that men should remember, but which they ofttimes forget when health makes them strong.

And the doctor coming, she whispers to him: “It is a cable—shall I?—dare I?”

“Not yet,” says the man of science. “But tomorrow, perhaps, if all goes well. He is improving fast—thanks to his good nurse!”

“Thanks to his good doctor,” answers Louise with happy blushes, and goes back to her labors at Montez, Aguilla et Cie., very happy, to find on her desk plenty of work.

It is mostly routine labor that she can answer without dictation, for a note has been made on every letter. She goes to work at these, for Aguilla, who comes in once, says: “I am cabling to Paris. I shall have nothing to say to you of what I spoke of last night, until I receive answer,” and keeps away from the office, apparently very anxious as to his return despatches.

So the girl, stealing one hour from her work, to spend at the bedside of Harry Larchmont, comes back late in the afternoon, to finish up her letters, and sits writing at the typewriter, till all the other clerks have gone away and left her, and the rapid night of the Isthmus is growing near.

There is no one in the building.

She has finished her last letter, and is rising to go home, when the door opens with a bang, and a hoarse voice speaks to her. The voice of a man half-drunk with aquardiente—half wild with rage. She gives a gasp, and her heart beats wildly, for she, Louise Minturn, is standing alone, face to face with Domingo, the murderer of Alice Ripley and her husband.

His eyes have a pirate gleam in them, and his black heart is throbbing with deep pants beneath his black bosom, that is partly bare, for he has torn away the shirt in rage, or drunkenness.

She would fly to the door, but he closes it and locks it. The key goes into his pocket as he cries: “Lefort, the miser who is weeping for his gold, says mine is gone also! The miser sobs! The pirate kills!”

Next a cunning gleam comes into his eyes that are red, and he whispers: “You are the one who writes in the magic box. You take down the words in the air?”

And the girl gasps, “Yes!”

“Then put it down, that I, Domingo of Porto Bello, may swear to it, and hang this villain Montez—who has robbed me of my gold, and hang myself, Domingo!”

And the girl, with pale face and trembling hands, stands looking at him, and he with half-drunken voice, cries: “Put it down! Put it down, or I will kill you! Put down the story of the white lady with the pearls!”

Then Louise, sinking into her chair, with trembling hands, does as she is bidden, and takes down the story of the ex-pirate, crazed with drink and rage, told with the florid gestures of the tropics; delivered with the intensity of the savage.

“You know me, Domingo of Porto Bello?”

“Y—e—s,” falters Louise.

“Put it down! You know Fernando Gomez Montez, mule boy of Cruces, who calls himself Baron?”

“Yes!”

“Put it down! You know the night in’56, when we killed ‘em here—women and children—we killed ‘em?”

“My Heaven!”

“Put it down! You know the Californian—you know the Señor Georgio Ripley—the white lady—the lady with the pearls?”

“Yes!”

“Tell how we killed the man, and stole the gold and the woman! That Montez gave me little gold, and kept much! Put it down, how that night we tossed the dead man to the sharks!”

“My God!” cries the girl.

“PUT IT DOWN! Put it down how we bore the beautiful woman into the mountains, along the Gargona trail, up through the hills into the Cordilleras, over the old Porto Bello trail, grown up with weeds over which the mule stumbled, but I strode on. How the monkeys howled and the jaguar screamed as we passed through the tree vistas in the dark night; how the moonlight shone on us through the boughs and hanging vines and palm leaves. How the day came on—above us the birds and sunshine, around us things that love darkness—the crawling snake, the timid tapir, the crouching tiger. And the lady—the white lady—regaining her senses, cried to us, and we took her to the hut by the river, where she struggled, and cried to God for her husband. Mia madre! how she cried! Cried as the women cried on pirate ships, when their husbands were cut down by cutlasses, or pistolled before their eyes. I, Domingo, tell you so. Put it down!”

“Put it down how Montez told her he loved her. How the beautiful eyes shone with hate upon him! Tell of the lovely form drawn up erect! How she turned upon him in the hut, and swore to kill herself, by the God of Gods, rather than love him! How he, to see if we were pursued, left her imprisoned in the hut, giving her one day to decide whether she would love him willingly or unwillingly. How I, Domingo, watched her, that I might steal the pearls from her. I could have torn them from her, but she might have told Montez, and I feared Montez. And I fear Montez yet, for he is stronger—cunning little Montez! Montez el diablo muchacho!

“Put it down how she looked out of the little hut—out of the window, and saw the Indian snake charmer—the snake catcher. Tell how she watched across the river bank! How the birds fluttered frightened—how that awful snake—the one I have seen kill a comrade in Saint Lucia, when I was a boy on Laffite’s ship—the one they call the yellow snake—the lancehead—the Labarri of Guiana, and Macagua of the Caribs. How the Macagua, eight feet of living death, with black forked tongue that moves unceasingly, and lurid eyes that never quail, crawled over the bank of the river, in pursuit of the bird; how the snake charmer, with long branch, pinned his head to the ground, and seized him, and laughed in his very fangs, as I watched—I, Domingo, watched! Tell how the woman, crazy with despair, beckoned to the snake charmer, for she knew not his lingo, while he held it—the death spirit—the great long serpent with the bands of black upon his back, that tapered down and left all scales of yellow on his belly—the living coil with death at its head, and long, sharp fangs, from which the venom dropped—how he put it in a water gourd, and bound over it deerskin, and held imprisoned the living death, that would affright even a man like me—put it down!

“And the lady—the white lady—looking with desperate eyes—with eyes that were growing crazy—beckoned the Carib, and he plunged into the rapids, and waded across, for she held up one white pearl of the string to allure him to her—one glistening pearl, worth money anywhere. Put it down! And the man coming to her with his vase of living death, she seized from him the gourd that held the Macagua snake, and dropped into his hand the pearl. And the snake charmer laughed, and I, Domingo, knew a desperate woman meant death to one or both of us, if we entered into her hut, or death unto herself. How I chuckled: ‘Here is an unknown joy for Montez who will be coming soon, for Montez loves this woman with the sunny hair and the blue eyes, and skin white as the Santo Espiritu flower!’

“Then, as night comes on, Montez is back and says: ‘There is no pursuit!’ And I said: ‘Ha, ha! there may be?’ That was to myself, for I had seen her write something, but I knew not what she did with it.

“And Montez said to me: ‘Is she there?’

“And I said: ‘She is—go in!’

“I laughed—I, Domingo, laughed. And as he entered, I saw this woman rise up as a spirit of the sea! Her white limbs and bare bosom, the garments torn from them by the brambles of the forest, gleaming in the last sun rays; her eyes—blue as the waves and flashing like those of women who walk the plank.

“Upon this loveliness Montez one moment gloated, then he cried to her: ‘I love you! I will be your husband! I will take the place of him who is lost to you!’

“And she cried: ‘Never!’

“And as she cried out, Montez sprang towards her, and then, between them both, I saw her hold the living snake, and laugh: ‘Come now! I love this better than I love you!’

“And the Macagua snake, not knowing which to bite, waved his head, and hissed a sharp hiss, with his fangs uplifted, as she chased Montez with the living death around the hut, and then again around! And he with awful screams sprang through the door.

“And the snake bit her, and the woman cried: ‘I love him best!’

“And so she died! Put it down! Behold the story that will hang this Baron Montez, who robs me of my dividends of gold! Put it down! PUT IT DOWN! that I may swear to it—I, Domingo of Porto Bello—the last living pirate.”

But there is a swooning woman, who can put down no more, as Domingo, ex-villain, ex-murderer, and last of the pirates of the Gulf, staggers out, and says to the Frenchman, Bastien Lefort, who is walking moodily outside:

“I have put it down—what will hang the villain Montez, who has robbed both you and me, my Frenchman of the heavy heart! I have put it down!”

Notes and References

- ladron: robber (Spanish)

- aquardiente: liqueur made from sugar cane

Davis, William C. (2005).The Pirates Laffite: The Treacherous World of the Corsairs of the Gulf. Orlando: Harcourt.

Ramsay, Jack. C. (1922). Jean Laffite: Prince of Pirates. Austin Texas: Eakin Press. Jump to book.

This edition © 2021 Furin Chime, Brian Armour