Baden Baden. The German Wagga Wagga? For the non-Australians among you, the latter is a town in western New South Wales which does not derive its name from “the Aboriginal word for Italians” (an old joke based on the no longer so insulting term “wog”). But what of Baden Baden? A city in the state of Baden, which is famous for being a health spa, where, in Cobb’s time, upper class Germans used to “take the waters”.

In the Middle Ages, it was also a spa town, and had been since the times of Roman emperor Caracalla, as excavated ruins below the New Castle have proven. The German word for taking a bath is “baden”; so does the funny sounding double name simply refer to the town in Baden where people take baths? With such a history, one could be forgiving for thinking it did, but it’s just an older plural form for “the city of Baden in the state of Baden”. Whether you go for one in mud, water, or in the casino, the name of the town has nothing to do with taking a bath.

Casino? Yes, there’s also been a casino there since the 1830s, so Cobb would have heard of it. Surely you can’t go for a bath in the casino. Well, perhaps not, except for diving into roulette, baccarat or blackjack, but the word “baden” also has another meaning in German, “baden gehen“: not only to go for a bath or to go swimming, but “to go under“, in the sense of losing everything, which one often does in a casino.

Hopefully, our hero’s hopes won’t “go swimming” in this German sense in Baden Baden because of the recipient of his letter, the Grand Duke, being away in Heidelberg. Oh, by the way, there’s an old German schlock of a song called “Du hast Dein Herz in Heidelberg verloren” (“You lost your heart in Heidelberg”, meaning not that you went there for a transplant of this vital organ, but that you fell in love there). Will our hero get shot through the heart in this supposedly most romantic German town? Surely, not, but this terribly sentimental old tune reminded me of another when there was mention of the Grand Duke being saved from drowning off the Island of Capri.

I’ve added a link to this cheesier song about the island: “Wenn bei Capri die rote Sonne im Meer versinkt” (“When the red sun sinks into the sea near Capri”), which a German comedian turned into “Wenn bei Capri die rote Nonne im Meer versinkt“, which, sung to the same tune, translates to, “When the Red Nun sinks into the sea near Capri”. Perhaps you could change it to a Grand Duke almost sinking beneath the waves near Capri, instead of a suicidal or perhaps tipsy, drowning communist nun? — the former, however, being allegedly saved by none other than Sir Pascal Dunwolf?

Is it just me, but after remembering two terrible tunes, do things not bode well for the desperate mission of Ernest von Linden?

CHAPTER 7

CAUSE FOR ALARM

As Captain von Linden came near to the crystal stream the two ruffians pulled up the heads of their horses, and faced them about to the northward — towards their objective point; but the youth clearly detected some signal and a response pass between them, and he was sure they loosened their pistols in the holsters at the same time.

Ernest’s only trouble was this: He could not, in good conscience, fire a deadly shot upon one who had not made a demonstration of the same character against himself; and yet, if he waited for that, he was liable to he shot down like a dog before he could make preparations for his defence. He thus felt it to be a critical moment, knowing, as he did, that his life hung by a thread.

Once more, as the two men turned their horses as though to ride forward, he recalled all the circumstances to mind. He passed them critically in review, from the beginning to the end — from Sir Pascal’s prompt refusal, when his journey to the court of the grand duke had been first proposed, to the present time. He could now understand why the knight had so readily and with such apparent cheerfulness withdrawn his opposition to the visit. He had allowed him to set out upon his journey for the very purpose of leading him into this trap. In every way he stood dangerously in Dunwolf’s path of greed and ambition; and, if he could be stricken down in the wild depths of the dark forest, none save himself and his sworn tools would be the wiser.

There could be no mistaking the signs as he had thus passed them in review, and his resolution was quickly taken.

Even at a little risk he must make the rascals avow themselves, to which end he rode on a few paces beyond the brook, and there ordered them to halt. They obeyed instantly, and, without further orders, turned about and faced him.

“Roger Vadas, answer me. Wherefore have you hung upon my steps? — why thus waylaid me? Seek not to deceive me, for I know more than you think. Will you speak?”

The man thus addressed glanced towards his companion, but gained no help from the stolid look he there met. Then he looked towards the young officer, and, with a grin almost idiotic in its utter brutishness, he said:

“Look ye, Meinherr, I s’pose w’eve a right to travel this path, haven’t we? If you don’t like to see us ahead, just go on yourself, and we will follow.”

“That does not happen to suit me,” said Ernest, “and,” he added, drawing a pistol from his right-hand hoister, and cocking it, “you will answer my question, or I will put you beyond the power of answering forever-more.”

“Oho! That’s the business, is it? I rather think I can take a hand of the same kind.”

Then, to his companion, as he drew a pistol from its case, he said:

“Now’s our time Otto! Let’s finish it quickly!”

To hesitate longer would have been simply suicidal.

“Hold!” thundered the youth, rising in his stirrups, and taking a sure aim. “Mark me. If you raise that pistol I shall fire, and I am not apt to miss my mark.”

“Fire away, Captain. Such things as those you’ve got won’t hurt.” And he raised

his weapon to take aim.

That was enough for our hero. It told him that he had not been mistaken in his judgment, and that his life was aimed at. With a quick, sure aim, his finger pressed the trigger, and this time the faithful weapon did not fail him. A sharp report broke upon the air, and the ruffian reeled, and fell backward, lying for a moment supine upon his horse’s back, and then rolling off upon the ground.

With a fierce oath Otto Orson raised his pistol and fired; but he was not a marksman. In his mingled wrath and astonishment he had discharged his piece without due caution, and the bullet flew wide of its mark.

“Beware!” shouted the youth, as the ruffian drew his second pistol. “You are a dead man if you —“

A fierce oath was the response; the pistol was raised, but not fired. “Quick as thought Ernest had covered the mans heart, and when he saw that quarter was not to be thought of he pulled the trigger, and ruffian Number Two fell from his saddle, his weapon being discharged as he went down.

Our hero now dismounted and went to where lay the man last shot. He struggled to his elbow as the youth came up, and pressed a hand over the sore spot on his breast.

“Ah! Captain,” he groaned gaspingly, “you’ve done for me! Your pistols were loaded.”

“Of course they were loaded,” Ernest said, at the same time lifting the man’s head and offering him a drink from his flask. You did not suppose I travelled with empty pistols, did you?”

“But,” gargled the expiring wretch, brightening somewhat under the stimulating influence of the cordial, “you said Balthazar came to your chamber with the letter.”

“Ah! — and he was to have drawn the charges, was he?”

“O! — O! — O! What care I now? Yes, he was to have done that thing- Sir Pascal — 0! him! — swore that it should be done.”

“And Sir Pascal sent you out to waylay and kill me?”

“Yes, yes. O! If I’d known that your pistols were —“

Ernest offered him another pull at the flask, but he could not swallow. His eyes glared wildly for a moment; his lips paled arid parted; a deep moan escaped him, another imprecation, half uttered, upon the man who had sent him to his death, and he breathed his last.

The youth arose, and went to the side of the other; but he was beyond human aid. He had been shot through the heart, and had died instantly.

For a little time Ernest gazed upon his work in solemn silence. It was not a pleasant thought that he had taken two human lives; but he could not blame himself for the deed. He was only sorry that the deeper, darker villain who had planned the wickedness had not himself come out to execute it. However, upon looking down upon the two faces, and marking the characters unmistakably stamped thereon, he felt in his heart that the world would be the grainer in their deaths.

He pulled the bodies on the side of the path, leaving them in such position that any who might be sent out in search of them would readily find them; then he reloaded his pistols and resumed his journey, destined to no more adventure on the road.

It was after nightfall when he reached Baden-Baden — too late to think of waiting upon the grand duke on that day — so he sought a comfortable inn, where he was acquainted, and secured lodgings. On the following morning his first movement, after having eaten his breakfast, was to call upon the banker of the baroness, from whom he obtained all the money he required, and then he bent his steps to the ducal residence. But only disappointment awaited him. The grand duke had gone to Heidelberg, and none could tell when he would return; and he was further informed that it was seriously in contemplation to remove the seat of government to that old city. The ancient palace of the Electors Palatine was being repaired and refurnished, and in all probability Leopold would ere long make it his permanent abode.

Residing at Baden-Baden and connected with the court, was a justice, named Arnbeck, who had in other years been Ernest’s tutor, and upon him our hero determined to call, thinking he might gain information that would be of value.

Herr Arnbeck was an elderly man; a professor in the college in his younger days, and now a judge in the higher court of law. He had been tutor of Leopold, the present grand duke, having in that capacity accompanied him during a two or three years’ residence abroad. He received Ernest with marked kindness, glad always to meet those pupils whom he had loved and respected; and he cheerfully offered any assistance in his power to render.

After a brief conversation upon current topics, chiefly of the grand duke and his contemplated change of residence, the young man stated the particular business that had brought him to Baden-Baden. He knew that his hearer was to be trusted, and that his sympathy would-be with him: so he told the story plainly from beginning to end; told of his love Electra von Deckendorf, of their betrothment at the baron’s own desire; told how they had grown up in love, looking upon marriage as a settled fact; and then he told of the coming of Sir Pascal Dunwolf, together with the strange plan of the grand duke for his marriage with the beautiful heiress.

Arnbeck listened with deep interest, asking several questions for further information, and in the end he was sensibly affected.

“My dear boy,” he said, speaking with something of the old school-day familiarity, “had one whom I had not known told me your story I should have doubted its correctness, but I cannot doubt you; and moreover the whole thing bears the stamp of fact. Let me tell you one thing in the outset: Leopold was unfortunate enough to have his life saved by this Sir Pascal Dunwolf. It happened in the Bay of Naples. Sir Pascal had been appointed on Leopold’s suite by his father, the Grand Duke Rudolf. Off the island of Capri my dear pupil was knocked overboard by the jibing of a boom, and Pascal, who had been sitting by his side, leaped into the sea, and upheld him until the sailors could bring the boat around and come up with them.”

“But surely,” said Ernest,”he would not on that account suffer —“

The old justice put out his hand.

“Listen to me, my son. Think no evil of Leopold. He is young and impulsive; his affections are strong, and his gratitude deep and abiding. He never forgets a favor. So I can see how he has hoped to bestow a benefit upon the man to whom he owes so much. You may be sure, however, that Dunwolf has misrepresented matters to the grand duke. Was he ever at the castle before? Did the baroness know him of old?”

He was there several times, I believe, in the baron’s time. I think he was attachcd to the staff of Rudolf.”

“Yes — as due of his aides. There is no doubt in my mind that he has represented to Leopold that he would be warmly welcomed by both the baroness and her daughter. He had probably seen the young lady.”

“Yes. He had seen her at court. She was there with her mother about two years ago.”

After a little further discussion of the subject it was arranged that Ernest should remain and dine with his old tutor, and meantime he — the tutor — would go out and make enquiries. Business called him to court, and he would there investigate.

Herr Arnbeck was gone longer than he had anticipated; and when he returned there was a cloud upon his face which he could not hide; but he would say nothing until after they had eaten their dinner; nor would there have been opportunity, for, on entering the eating-room, they met there the justice’s wife and two daughters, all of whom remembered the visitor well and kindly, and even affectionately.

At length Herr Arnbeck and Ernest were again alone together, the latter being very anxious to know what his aged friend and counsellor had to say to him. The host did not offer his visitor a seat; but, standing before him, he laid a hand kindly and paternally upon his shoulder, saying as he did so:

“My dear boy I have made all possible inquiry, and such information as I have is at your service. Sir Pascal did certainly represent to the grand, duke — in short, he told him, in direct terms, — that the Baroness von Deckendorf would gladly welcome him as a son-in-law; and that she was the more anxious since her daughter had conceived an unfortunate attachment for a vagabond hunter, who, in all probability, belonged to the band of the notorious Thorbrand. This he told her so soberly, and with so much of apparent feeling, picturing in vivid colors the grief and chagrin of the outraged mother, — that Leopold believed him, and at once turned his attention to mending the matter, which he would do by exercising his regal prerogative of guardian of the orphan heiress, and bestowing her hand upon the valiant knight.

Several times during this brief recital the youth had seemed ready to go wild in his wrathful indignation; but thought brought deeper and calmer feeling; and his first coherent speech was of what course he should pursue. Would it be well for him to push on to Heidelberg, and see the grand duke?

“No,” said Arnbeck, with a solemn shake of the head. Though I am confident Leopold would givn you quick relief, were you to see him, yet you had better not waste time in running after him. It is his plan to visit Wurtemberg before he returns, to make investigation into the matter of an uprising — a revolt — led by the very Thorbrand of whom we have spoken.”

“I have heard a whispering of something of that kind,” said Ernest, “but I gave it no credit.”

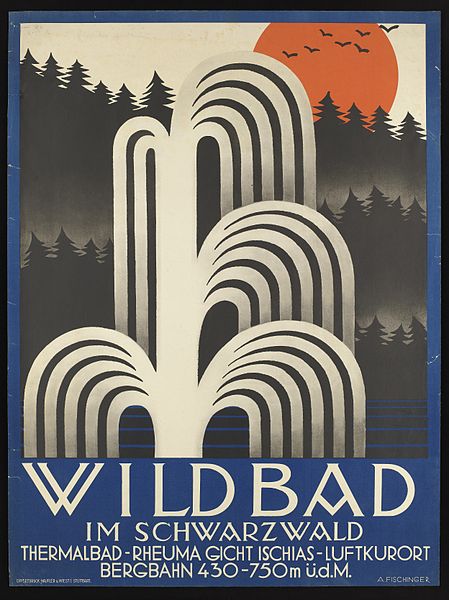

“Nor did I, at first, returned the justice; “but I am now forced to the belief that there is much to fear, if prompt measures are not taken to nip the mischief in the bud. In the depths of the Schwarzwald, on the confines of the two principalities, there is a large number of disaffected people, with no grievance save poverty, who are ready to join the robbers, thus making a host capable of terrible work of plunder and devastation. It was to look after this rebellion, and to assist in crushing it; and, afterwards, to hold the uneasy ones in subjection, that Dunwolf was sent to Deckendorf.”

“My dear old friend,” said our hero, with a proud flush in his face, and a kindling of his truthful eyes, “I may say to you what I would not say to another. Leopold of Baden had better trust me with that command, than trust the man he has sent thither.”

“I believe you, my dear boy; and I will bring it to pass, if I can. Meantime, my advice to you is, — Return at once to Deckendorf. Since that bad man has been so boldly wicked as to attempt your life, there is no telling what he may do next. Now that he fancies he has put you out of the way he may carry a high hand with the marriage. With the commission as given him by the grand duke, and the consent to the union therein implied, there is nothing in the world to prevent him from forcing the marriage at his will. He has only to find a priest ready and willing to do his wicked work, and they, I am sorry to say, are plenty. So, my son, — back to the castle, and look to those who may need your protection.”

For a little time the startled youth was utterly unable to speak. So confounded was he that he could scarcely think. The danger that threatened his beloved had come upon him like a thunderbolt from a clear sky. He had not dreamed of such a possibility. The idea that any living man, less than the emperor, or the grand duke himself, could do such a deed as force an unhallowed, unwelcome marriage upon the heiress of Deckendorf, would have been too wild and ridiculous for belief.

“Herr Arnbeck!” he gasped, as soon as he could command speech, “would such a marriage as that — forced upon the lady against the earnest protest of herself and her mother — be valid?”

“I am pained to say, Yes. Electra von Deckendorf is, in the eye of the law, a ward of the grand duke, and he has given his consent to her union with Pascal Dunwolf, which consent the prospective husband has in his possession in writing, in the prince’s own hand. You can see for yourself the power possessed by that dark-browed knight. But, mark you, he must act quickly if he hopes to succeed in his nefarious purpose; for, as I have promised you, the moment Leopold knows the truth, that moment Dunwolf’s power falls.”

“O! why is not the grand duke here? Why can I not find him? Heaven have mercy!” And the quivering youth wrung his hands in the uttermost depths of anguish.

“Hush!” said the aged justice, laying a hand upon his arm. “Be up and doing. Do you look to Deckendorf, and I will look for the grand duke. I know you will not find him if you go to Heidelberg. I shall hear from him on the arrival of his first budget, and I will not fail to notify him.”

With a mighty effort Ernest recovered himself, and as soon as he could think consecutively, and speak coherently, he thanked the good old man for his kindness, and promised that he would return to Deckendorf as speedily as possible. It was now too late to set out that day. The weather was thick and threatening, and the night was likely to be stormy; but he would be on the road early in the morning.

He took tea with the justice, and with him spent a portion of the evening. The conversation turned upon the trouble in the Schwarzwald, neither of them having any heart to talk further of Dunwolf and his villainy. Ernest asked if there were any men of standing and influence engaged in the insurrection.

His host answered that there probably were, but they were not positively known. The plan, as nearly as it could be arrived at, was to form a vast and powerful organisation of freebooters. They would organize a government, and live by general plunder. Having gained possession of a few of the strongest castles in the heart of the Schwarzwald, they might bid defiance in their mountain fastnesses to the world. It was known that Thorbrand was engaged in the enterprise, and he appeared to be the ostensible head of the movement, but it was doubtful if he was the responsible head.

“Have you any idea who is the responsible head?” asked the youth, earnestly.

The old man returned him a sharp piercing glance, and then arose from his seat and took two or three turns around the room. By-and-by he stopped by the side of his guest, and laid a hand upon his shoulder.

“Ernest, what I now say to you, you will sacredly keep as a trust reposed under seal of your honour. You have asked me a direct question. I will give you a direct answer: SIR PASCAL DUNWOLF!”

The young captain started as though he had been stricken a heavy blow.

“Hush! Not a word!” added Arnbeck. “I have never thought this until within the present hour; but now I sincerely believe it. Bury it in your bosom — bury it deeply — and keep your eyes open. And now I must bid you good-night. I have work to do; and you must gain sleep, if you would perform your journey on the morrow.”

A little later our hero returned to his inn and sought his rest; and on the following morning, bright and early, he was on the road. There had been rain during the night, but the rising sun soon banished the clouds, and the day promised to be clear and pleasant.

Notes

- his sworn tools: his lackeys, flunkeys.

- be the grainer: this obsolete idiom carries the sense, “be the beneficiary,” presumably after the agricultural metaphor.

- Electors Palatine: “[A palatinate was] Either of two historical districts and former states of southern Germany. The Lower Palatinate is in southwest Germany between Luxembourg and the Rhine River; the Upper Palatinate is to the east in eastern Bavaria. They were once under the jurisdiction of the counts palatine, who became electors of the Holy Roman Empire in 1356 and were then known as electors palatine” (yourdictionary.com). Elector: “a German prince entitled to take part in the election of the Holy Roman Emperor; [E.g.], the Elector of Brandenburg’” (Oxford Languages).

- Wurtemberg: “The Kingdom of Württembe.rg was a German state that existed from 1805 to 1918, located within the area that is now Baden-Württemberg” (Wikipedia).

- arrival of his first budget: “budget” from OF bouge, “a bag”; so carries the sense, “immediately on his arrival.”

- freebooter: robber, plunderer.

- fastness: stronghold (see also Chapter 6 and n.)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.