Eulogy for an Unfinished Cat

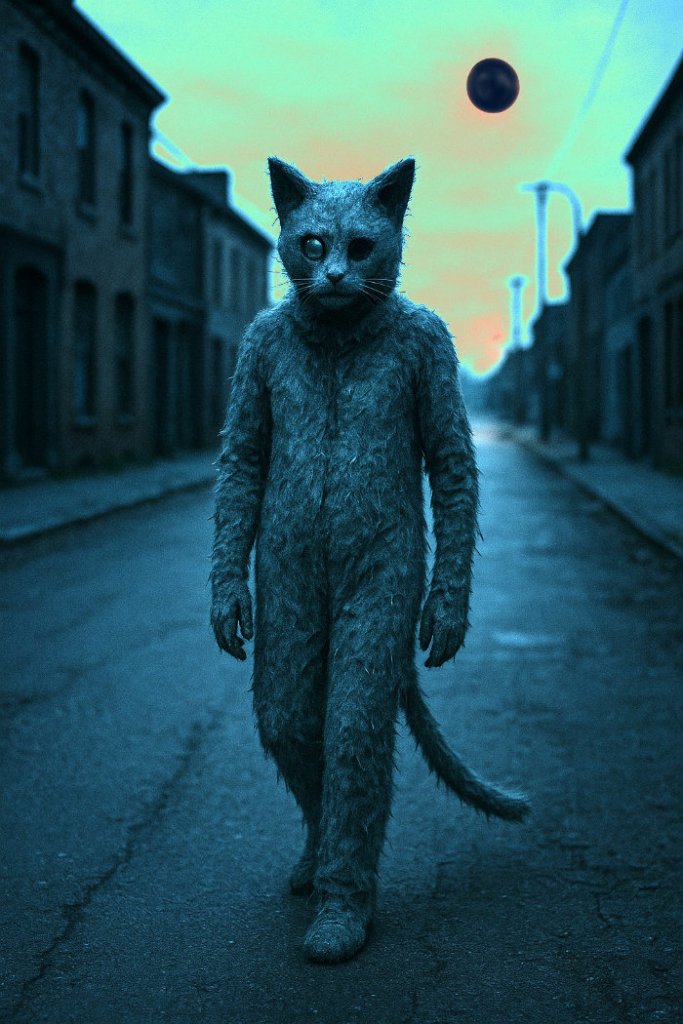

Dressed as a cat I traipse through the streets and lanes of yesteryear, a mystery of mind so despised, so unperceived, that this territory marked by squirts of indifference (over many years) has never been gained at all.

A quiet squat in the crepuscular light. Who am I but an indistinguishable feline made final by fractals of form? By the moon’s shifting gleam, its play of light perfect upon this silver-blue fur. Desolate, quiet, pin-prick final, cutting to the quick of my core.

This one’s for the cat-people. For those made lonely by the dysentery of experience, or time’s dismal episode flickering on TV like a brain that does not matter. This one’s for the long-distance lovers sifting through their screens. Searching for solace within a shame that reverberates beyond the data-stream and which connects us by our sorrow.

I have seen the man who walks these streets carrying cane and dressed in black. I watch him through a knotted hole in a wooden fence. This Catherine Wheel dream circulating beyond the vapour rising from my ejected waste. A territory marked, a form found; (one in keeping with my inevitable demise). A sigh, then relief … A moment during which the transition to humanity begins, then is at once complete. This eye is glass but the orb is deep. The flesh advances, putrefies … My troubled tail collapses from one too many lashings. This cat, in all her fractious wonder, finally, she sleeps.

The Tar Machine

home

family

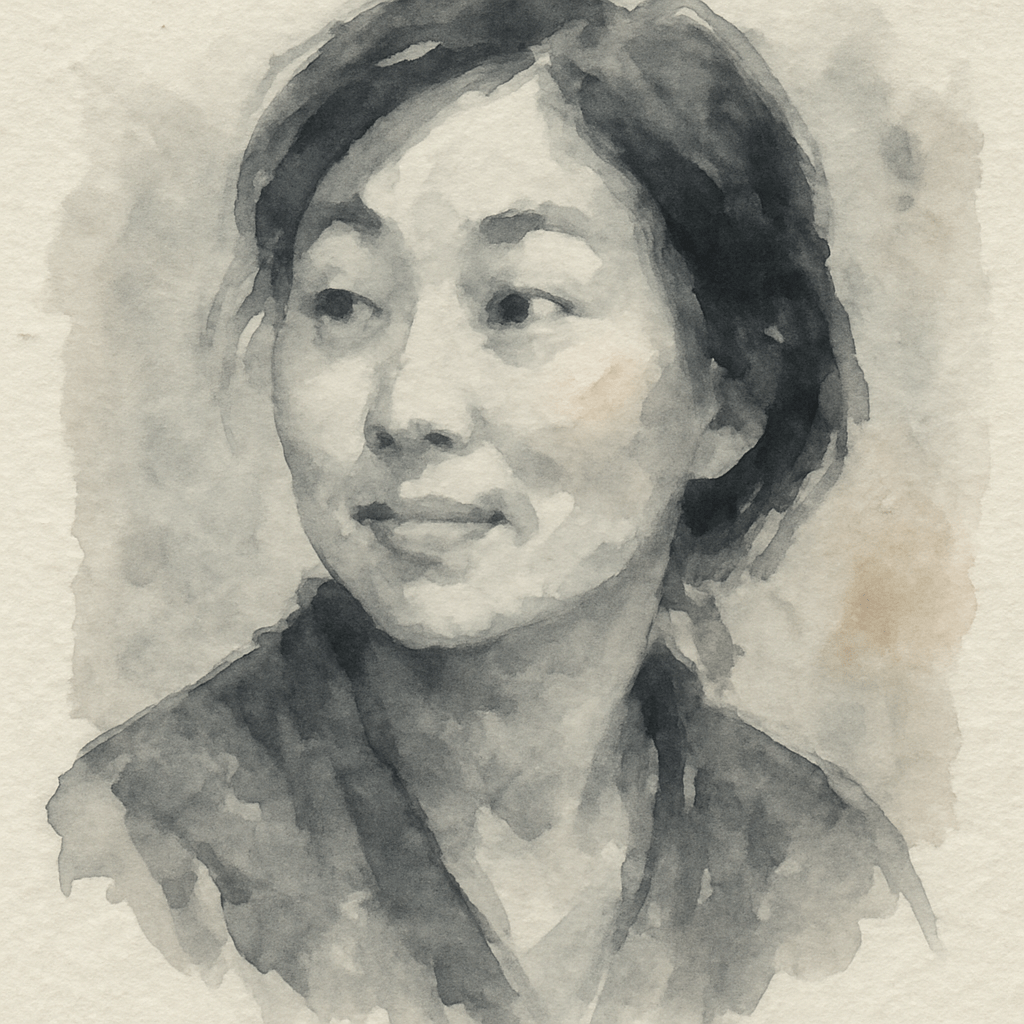

mother

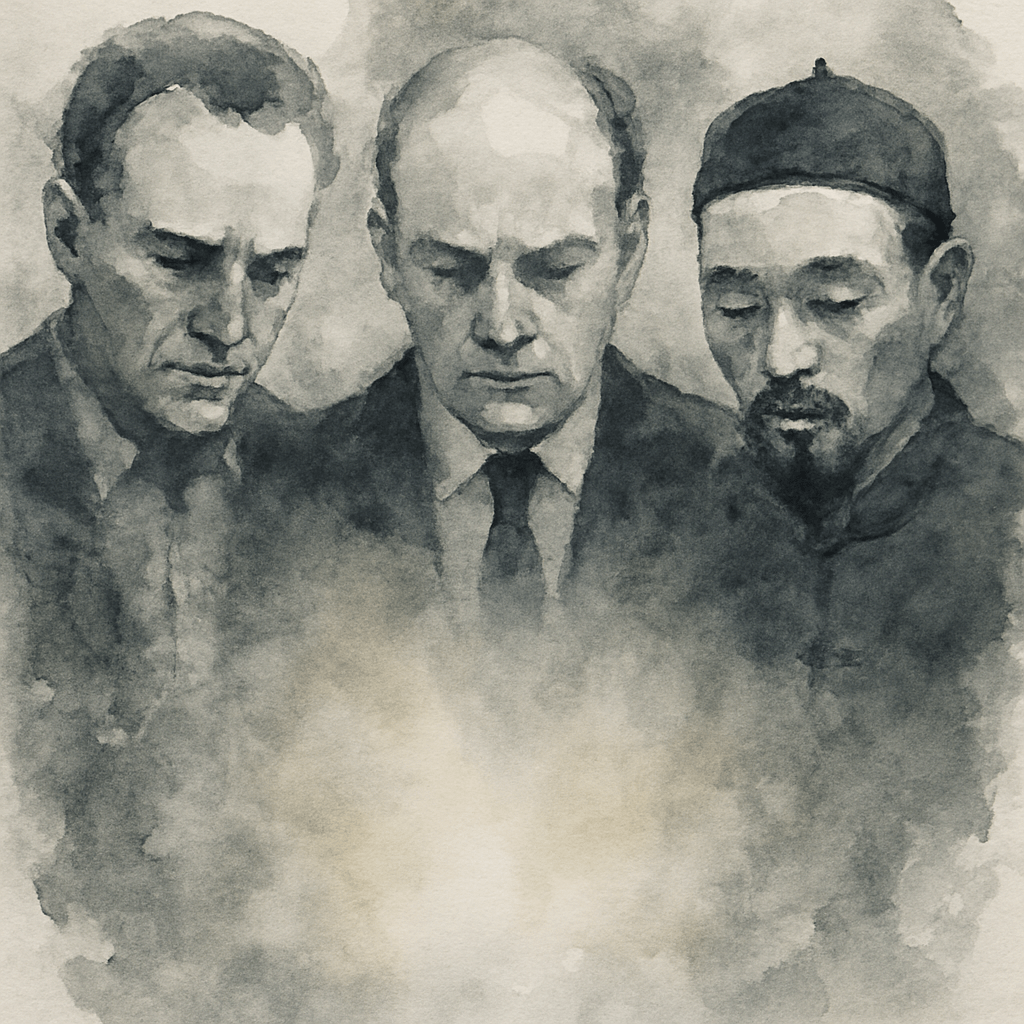

father

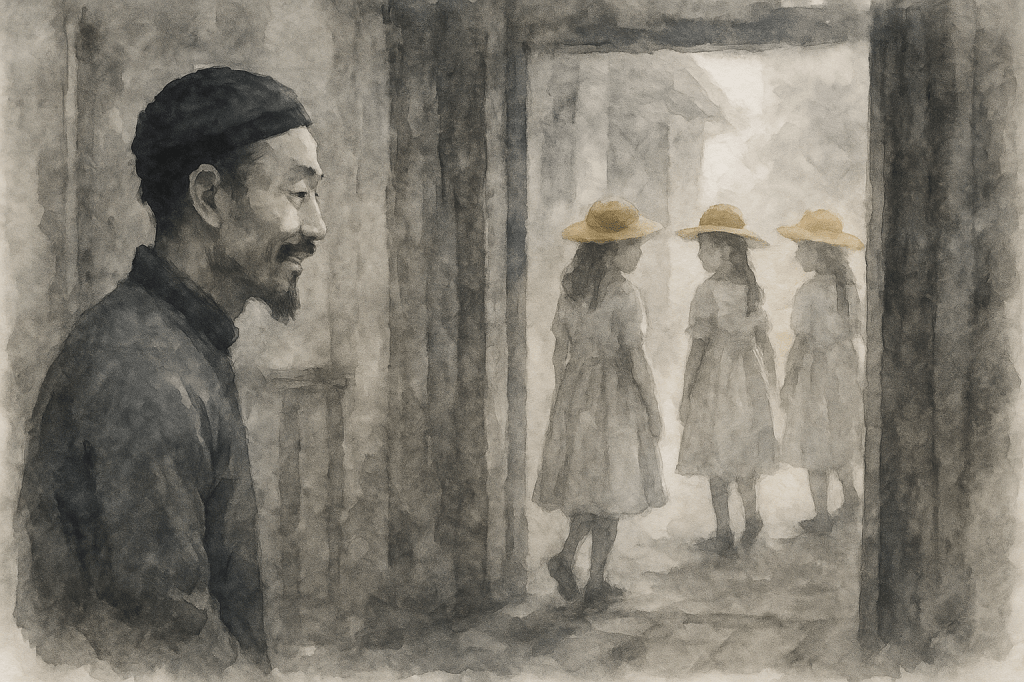

sister

brother

strap

leather strap, spray, wind, the leather strap lets fly like the tail of an angry puma, black cat, yellow eyes, her name is holly, holly stares at her surroundings from the safety of her cane basket, the black and white tiled kitchen floor is a precipice that requires the most sensuous negotiations of the four paws of a cat, even if there was a mouse dawdling along the skirting board holly would not be interested for survival is foremost in her cat’s brain, all mice can wait, there will be time to play when the job is done

inside the house seen through the yellow eyes of holly the cat, she stands, she expands both this way and that, the fur on her back like iron filings drawn to a powerful magnet secretly implanted in the ceiling, holly’s fur, it has a life of its own as it leaves her spine, a flock of fine hair scurries along the walls of this sullen room, and i, in my decrepit bed, i wake from dreams of long ago anticipating some relief, shake the sleep from my eyes, and discover for the forty thousandth time these bluestone walls and the sound of an unseen creek trickling outside, i do not rise from this mattress of straw, it is as if i must lever this body across time, and i can no longer remember whether this exacerbated cat was once a childhood pet or has always been a black and hissing figment in my mind, my hair, black as well, yet inferior to holly’s, it hangs across my face, oily, traces of grey, how long have i been in this room, did i arrive yesterday on a star descending past the moon as it streaked across the universe, no matter, these walls, the sound of that creek, and holly’s tail insinuating itself into my ear, her unclipped claws hooked into the flesh around my shoulder blades, and rip with a flourish, and rip with another, and my skin descends toward the base of my spine in curlicues that gather between the pads of holly’s paws, i once administered pain, i have spilled blood and drank it and rubbed it across my chest, created a pattern from someone else’s misery, only to have their misery become my own in this room, behind these walls, with holly on my back inside my mind tearing strips from me, exposing the ribs of a time that seems so ancient, if only i could find words that would adequately express this sinister dream inside a mind rupturing within the remembered blood of someone else’s misery, these words i cannot find are walls to the sound of that trickling creek i imagine runs through a field on the outside of this room, daisies, sunshine, these words are so inadequate, they do not inspire, and my dream drifts back into this room, behind these walls, exhausted, i dump my body back on this bed and realise the idyllic creek outside is just the sound of metal coils contracting beneath my weight

rupture, jenkins, and yes, i run my fingers through my hair, feel the greasy touch of whiskers covered in human oil, and yes, i remember a man named jenkins, his soul split by experience, and yes, jenkins, he wore black horn-rimmed glasses like antelope horns belonging to the twisted cape of some disfigured shaman, and his stories, they were of the blackest kites swirling in a cumulonimbus sky, jenkins stories breaking his listeners bones, scooping out the marrow they believed in, replacing it with a dowel of the blackest type, until it was jenkins who was able to make his listeners fly upon recitals of his disfigured shaman’s dreams, this story of green leaves turned grey, decomposed and banking up along the seams joining the walls inside this bluestone room, and jenkins, you sit here now, your grey hair in strands across your scalp, leaving the slightest freckle revealed, what is inside your head jenkins, what sits beneath that freckle, is it a manifestation of the sprinting cancer inside your body, talk to me jenkins, tell me stories from inside your room, is it like mine jenkins, or are there many rooms, one containing a kitchen table, a silver room jenkins, you are a lucky man, let me hear the story of your silver room jenkins, tell me jenkins, explain the specifications of your room, talk jenkins, i will listen, i will abide by your regulations, it is fortified with steel, your wife stands by an ironing board, her tongue extends toward you, entering your ear, you feel the sound of her tongue entering your ear and your perceptions are momentarily disfigured, a split of the soul jenkins, your wife, she has control, for it is your ear inside her mouth when she swallows, and yes jenkins, your story is one of love floating high on air clouds whipped by currents into a cumulonimbus sky, and jenkins, what has become of this thing, this globule of ectoplasm that we thinly, that we inadequately describe as a soul, is it spread amongst green fields inside the highways and streams that make up the vascularity of your interior, are you totally diseased jenkins or is this infection confined to the flesh beneath your missing ear, talk jenkins, i will listen, talk jenkins, speak, and you are silent, and i am feeble, and jenkins, we shall sleep now, and continue our disfigured dissertation when we wake

silver room, silver lady, the lady inside the silver room dances with a broom extending up her arse and out her ear, she thrashes at experience, sweeps life into a time when her mind was frozen, when sand gathered in the corners of this bluestone room, she visits me now, the lady inside, she leaves her silver room and crawls from jenkins sleeping ear, i wake, her arms and body heave and sway in front of me, inside the mountain with a thousand caves that is her torso, those ribs, the ribs of the lady inside, semicircular, smooth ivory ribs, bones of experience, i want to extend my hands through her pink flesh, to visit the interior of her torso and run my fingers along those ribs, like whalebone, the lady inside, her ribs, engraved by the finest cartographer, diagrams as yet unreadable, must get closer, leave this forlorn room of broken dreams, and yes, feel the edge of my dirty fingernail trailing along the inscriptions etched into those ribs, of pathways to the sea, of men in ships, their beards flaying in the wind, of diagrams incised upon the life of the lady inside, and it is the ship that i must see, for it is the vessel that transported my father to this house of hawthorn brick, his memories, his experiences, his fantasies inscribed upon my spine, that spineless act of pissing in a gumboot for fear that your father would rip his love away from you, and yes, it is love at the core of these wretched dreams, it is love that was ripped from me in that house of hawthorn brick, at first, its doors and windows were open to the sun, that house sucked in the juice of spring, dispersed pollen along corridors that degenerated into sand and dust, now, i sit inside this bluestone room, these cold walls, these walls made from thick ice, where memories leak into the general surrounds, memories of a man named jenkins, he sleeps next to me, the freckle on his head alive with the sound of his disfigured brain turning each thought over, each memory, of the woman inside, jenkins wife, who bit off her husband’s ear for fear that he would become contaminated by the goings on inside this bluestone room, these walls, the sound of incessant dripping, gaining speed, becoming a trickle, outside i hear the creek become a river as it races towards the sea, the swirling waters of the mouth of a river regurgitating its soul into the sea, come jenkins, find your feet among the grime, do not slip, struggle jenkins, take your hand away from the place that once held an ear, listen, force yourself to listen as we chip holes through these walls of ice, feel the fresh air of a future life seep into the stale degeneration of this bluestone room, sniff, taste, hear, touch a life that lies paved and spread before us, extending through green fields into the distance, a small creek running alongside us jenkins, running with us, smooth stone experiences to come jenkins, let us walk, and when we are tired we shall sleep once more

and yes jenkins, do you see the stag, its velvet covered antlers a complex of possibilities, presenting pathways jenkins, which path do we choose, it is your turn to choose jenkins, you, the man who turned up that lucky wildcard, your life jenkins, what a laugh, it always seems to rise from somewhere at the bottom of a deck, on a ship, etched into the rib bones of the lady inside, my father, jenkins, jenkins, my father, i walk with you into walls, our heads, our eyes confronting one another yet all this time those pig eyes of yours have prevented me from seeing that you jenkins, you are that father that ripped your love from me and spat it into that bluestone gutter outside that house of hawthorn brick, i love your disfigurement jenkins, want to press my fingers into the pulp beside your temple and elicit strands of love from inside the recess of your brain, a tendon of love jenkins, i suck your love through my lips, it slithers down my throat, it burns the oesophagus, i will eat your entire mind jenkins, my father, i will eat the worms in your mind and shit them back into the sea, in the hope that, in the hope, there is no hope, there is only you jenkins

Tony Reck © 2025