Autopsy at the Junction Hotel

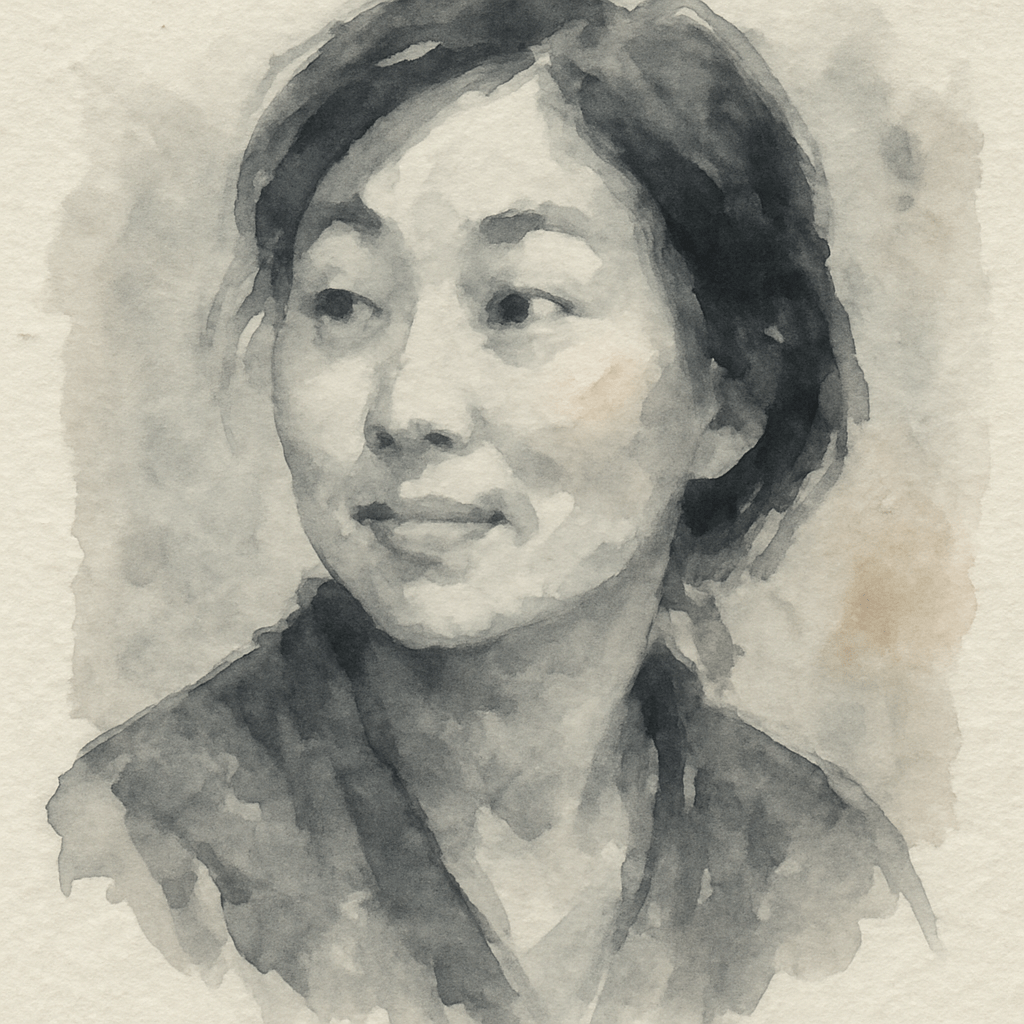

Sound of hooves and iron‑shod wheels on gravel reached the Junction Hotel door, a rare interruption in the sleepy settlement. Huish‑Huish brushed back her hair before going to answer the knock. A detective stood at the doorstep, one finger tapping lightly against his thigh. He was waiting for Mow Fung to answer, a name he knew from the licensing roll. He had driven from his headquarters at Stawell, only a few miles away.

“Mrs Mow Fung, I presume? I am Detective Forster.” He made a slight, polite bow. A nervous man, a lean man, she observed, and the lean, nervous man removed his grey felt hat and fingered the brim. If he meant to unsettle her, he’d have to try harder. She caught the tang of carbolic soap clinging to him in the close air of the doorway. It suited him somehow. She ushered him into the bar. Theirs was a modest establishment, but scrubbed spotless. The faint smell of lamp oil and aged wood lingered in the cool interior, a scent that seemed to settle into its polished tables and floorboards. She had been topping up the lamps, and a tin container of oil remained open on one of the tables, next to a neat pile of linen squares.

They passed the bottom of a staircase, halting at a child’s footsteps that came thumping down.

“Mama! Alice won’t eat her porridge. I’ve told her and told her but she just picks at the egg and won’t touch anything else.”

The mother suppressed a sigh. Such was the morning ritual. “Tell her the police have arrived. Once they deal with your father, I will have them deal with her too, if she is not careful.”

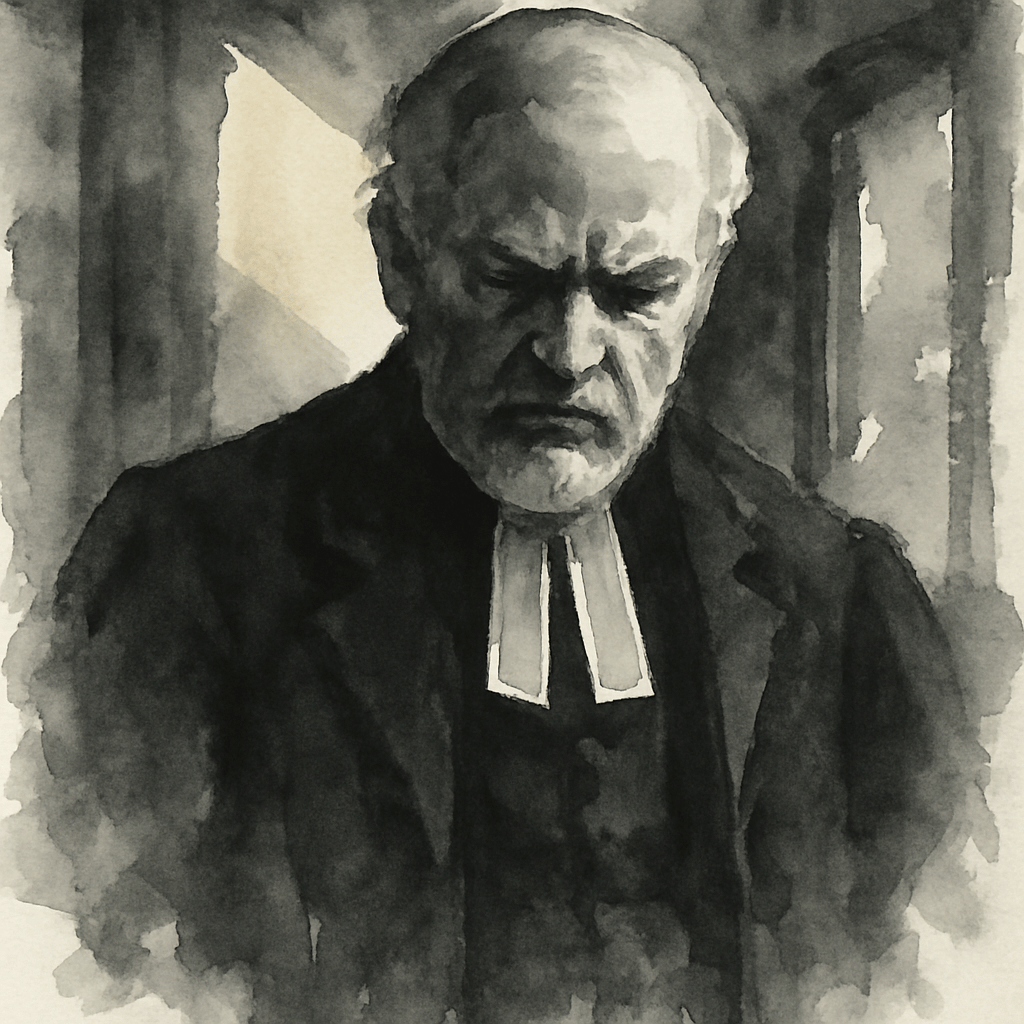

Detective Forster could not prevent a cough, but immediately resumed his grim composure.

The girl, aged twelve or so at most, ascended a few stairs, halted, unafraid but inquisitive.

“What will they do with her, Mama?”

“Use your imagination!” Huish-Huish was outdone – the child was incorrigible. “Now make them eat their breakfast properly and off to school with you! Foolish girl.”

The daughter climbed the stairs with purpose, the hem of her uniform brushing the narrow boards.

The mother stopped at a door halfway along a dim, unadorned hallway. The air smelled faintly of cold ash and last night’s cooking fires. From behind emanated the ghost of a voice. No distinct words, but what the newspapers mocked as “Oriental mishmash.”

Turning to Forster, she said, “My husband is inside here with the gentleman.”

“The others have already arrived?”

“Only the dead one so far,” she said with a smile. “Mow Fung is a very silly man, who nurtures some foolish superstitions from old China. You must forgive him.”

But she did not go barging in. There may be others. She laughed softly. “He daydreams, fantasises he communes with the dead. You know, he sinks down into the Ten Courts of Hell and has a bit of a chat. Haha!” She said it in a melodramatic tone with a gently mocking lilt.

The faint chant in the room faltered, as if aware of their intrusion, then died altogether. She pushed the door open. The candle was out. The trace of a strange perfume lingered in the air. His odds and ends were tucked neatly out of sight. Forster felt the change in atmosphere as they stepped in – the pall was unsettling after the murmur that hung in the hallway.

Mow Fung drew back a curtain, and the morning sun slanted through a haze of fine dust. He smiled at Forster and bobbed his head in a dumb-show of humility. There was something indefinably unusual about the fellow, Forster thought.

A noise of wheels and hooves announced more visitors, and Huish-Huish left the room to meet them. Forster jotted a few notes in his pad as he examined the corpse.

“This is exactly the same state it was in when it arrived yesterday?”

“Of course, detective,” Mow Fung said.

“You haven’t touched it?”

“Touched it?” Mow Fung repeated. “Good idea. A very good idea! You are an excellent detective, I see that already. Splendid.” He pressed his palms together in a position akin to prayer and nodded. Forster found himself almost infected with the broad smile.

“Very nasty business,” said the oriental. “Murderer came up from behind, a trusted companion, a good mate. Never knew what hit him!”

Was that a laugh? A cackle? What was wrong with these people?

Forster stepped to the table and took hold of the neck of the cadaver, stretching the flesh about the open wound. A sharp instrument had been used: an axe, probably, or maybe a tomahawk. The weapon evidently slipped in its course at first, creating minor abrasions before cutting right in through the neck.

He turned to the Chinese man.

“Mrs Mow Fung tells me you have been … communicating with the deceased,” he said.

Mow Fung smirked. “The missis,” he said, “is a silly woman who nurtures some foolish superstitions from old China.”

Forster gave him a piercing look. “Be so kind as to tell me, then, how you could have arrived at your – your deduction otherwise?”

At that moment, Doctor Bennett, the constable, and Henry Wilson – the miner who found the body – came into the room. Bennett cut Forster’s introductions short to begin the post‑mortem, and the constable took out his notebook. Forster and Mow Fung took chairs, while Wilson remained standing nearby, arms folded, watching in silence.

“A European. Body very dried up. Bad state of decomposition,” Bennett dictated. “Much of the skin has been eaten away – particularly from the arms and legs – torn off in patches, very much dried up and leathery. A good portion of the integuments is gone.”

“A lot of wild cats out there at them old Four Post diggin’s,” Wilson volunteered, but Forster silenced him with a look. “We’ll go through all that later on,” he said.

“Too far gone to examine the internal organs,” Bennett continued. “The head is off – missing. It wasn’t found at the location, I take it?”

The constable shook his head. “No, sir.” Of course not: some things the bush will not give back.

“The upper margin of the skin on the neck has been divided by some sharp heavy instrument. About an inch below the margin of the neck is a transverse cut through the skin, which extends down to the vertebrae, evidently made by the same implement, probably a hatchet or axe. No other marks of violence. The upper margin of the neck is indented as if by a succession of cuts. The head has evidently not been severed from the body by one single blow, but by several. One cut extends transversely across the neck. Numerous abrasions in the vicinity. The vertebrae have been severed with that heavy blade. No, I should not think it was done with one blow.”

“Not suicide then?” Wilson said deadpan.

Forster gave him a withering look.

The doctor continued. “I would estimate the height of the body to be that of a man about five foot ten or eleven inches. As for the length of time the body was exposed, I could not speak with certainty. But I would say any time from four weeks upwards – probably two months or so, to become dried up and mummified like this. Absolutely bloodless. From an examination of the bones and hair, I would conclude that the body was that of a middle-aged man probably between the ages of thirty-five and fifty-five years.

“Internal organs – those of the chest and abdomen – are very much decomposed, and in the condition of… well, pulp. From the upper margin of the neck to the heel is five foot one and a quarter inches; from the tip of the shoulder to the ankle, four foot nine. The frame is large-boned and that of a big man. Some of the hair of the beard is on the neck – reddish-brown hair mixed with grey. Skeleton is perfect. No broken bones.”

He drew a surgical saw from his case and cut off a piece of vertebra and two fingers, then scraped some sandy‑red hair from the neck. He placed the specimens in a jar, which he plugged with its cork stopper.

“Apparently after having consulted the victim in the afterworld, Mr Mow Fung here informs me that the deceased knew and trusted his murderer – enough to let him come up behind and take him by surprise,” Forster said.

The constable chuckled.

“Come on, leave off Sarge!”

His superior paid him no mind, studying the body as he spoke.

He turned to Wilson. “You discovered the body lying as it is now, Mr Wilson? On its back?”

“Yes, sir. On its back when I found it, and your coppers brought it here the same way,” Wilson said.

“Mm. Yet observe these abrasions on the chest, and the tiny stones impressed into the flesh – or where the flesh was exposed when he hit the ground. Even if the clothing was stripped away afterwards, the marks are clear enough: they suggest the body struck the earth face down.”

Forster leaned over the table, his hand hovering a few inches above the corpse’s limbs, tracing out their outline. “And note the awkward sprawl of the arms and legs. The hands, palms upward as he fell, show no attempt to break his fall. Whoever removed the clothing may have shifted him somewhat, but that detail remains. He never knew what hit him. A pretty business indeed.”

He straightened and glanced at Mow Fung. “Does my analysis accord somewhat with yours, Mr Mow Fung?”

Mow Fung said nothing, gazing clearly into the detective’s eyes, a hint of a smile hovering on his lips.

“I am a simple hotel-keeper. I am sorry – I do not follow your complicated talk.” Pensively, he stroked his sparse black beard (one day it may grow into a venerable white one). “Perhaps we do not see things as they are,” Mow Fung continued, “but as we are, as it was said in the old time.”

“Quite so.”

“Will I put that in, Sarge?”

“Might be a good idea to insert it as a footnote for you to incorporate into your own meditations, which I’m sure you engage in regularly.”

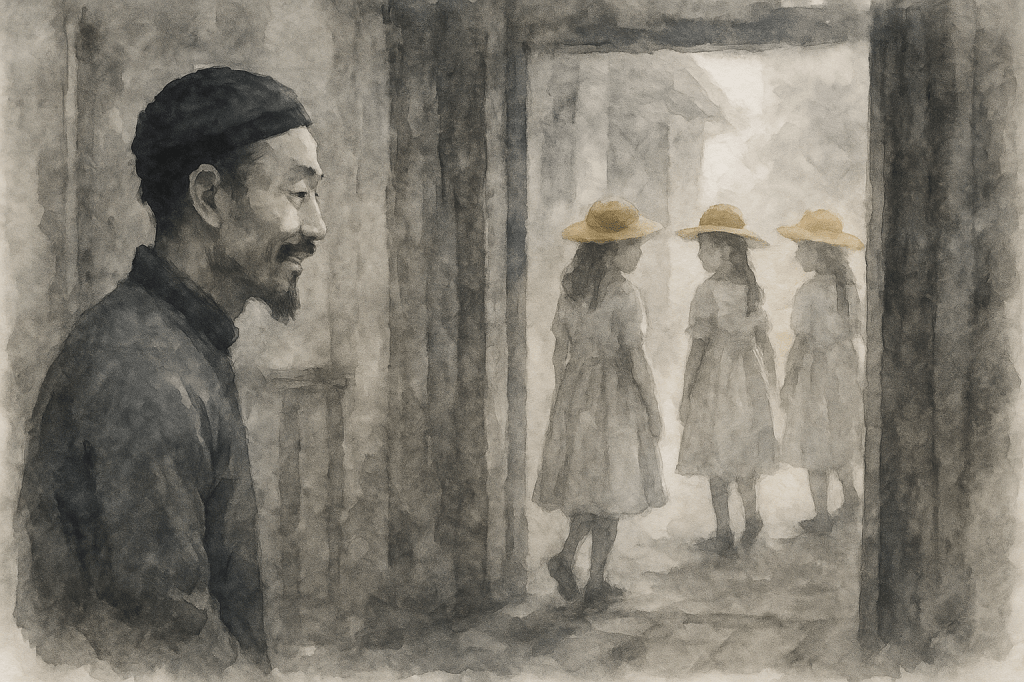

Mow Fung watched the buggies of the detective and the doctor, and the uniformed constable on horseback, recede at a leisurely pace down the dusty main street of Deep Lead – towards the old abandoned gold diggings on the Old Glenorchy Road. They rounded the bend, passed Bevan the ironmonger’s, and disappeared into the bush.

He met Huish-Huish coming in from the laundry with an armful of towels, their youngest daughter Alice trailing on her skirts. At that moment, the other daughters trooped down the staircase, Lena – the eldest at twelve years – herding her siblings. School uniforms and wide-brimmed straw hats floated in a bubble of chatter, expressing such immediate and minute issues as are memorialized perhaps in the record of human souls, but seldom if ever recalled in human life. “Hurry now,” Huish‑Huish called. Alice was moaning about the porridge. Lena hesitated at the threshold as the others spilled outside, her hand lingering on the doorframe.

Mow Fung could not refrain from a smile and faint shake of the head as they left with no fare-thee-well, though Lena struck him as older than her years. His eyes followed the children as they disappeared, then shifted to the bush beyond the paddocks. He remembered what Wilson had said: the body had been found at the Four Posts. He gazed at the bush a moment longer, the name settling uneasily in his mind.

Images generated by AI