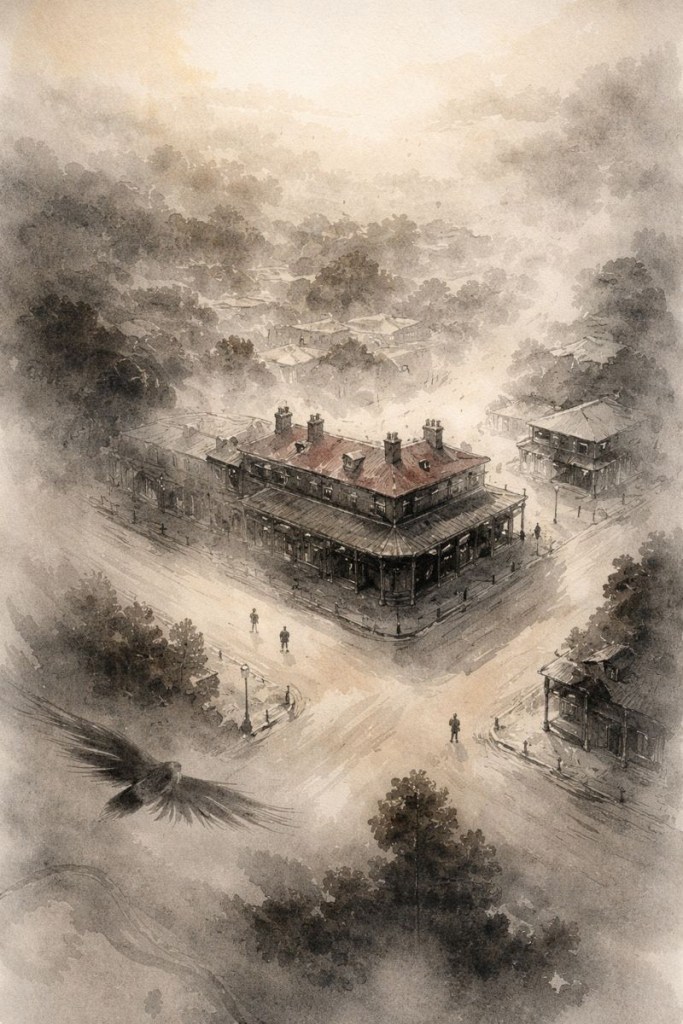

“Must be about seven or half-past,” Burns thought as he walked up to Fergus’s European Hotel, the morning after he and Forbes had tramped off along the old Glenorchy track. Finding the front doors locked, he went around the side, in through the gate and past a pile of empty kegs, where a back door on the bar-side of the pub stood wide open. He was halted by the sudden appearance of his own ashen reflection in a large gilded oval mirror on the wall of the hallway.

He forced a laugh. “Thought you were a bloody ghost, but only my own self. What next?” he said aloud to the reflection. He wiped his brow, which glistened with a heavy sweat. The morning was already warm.

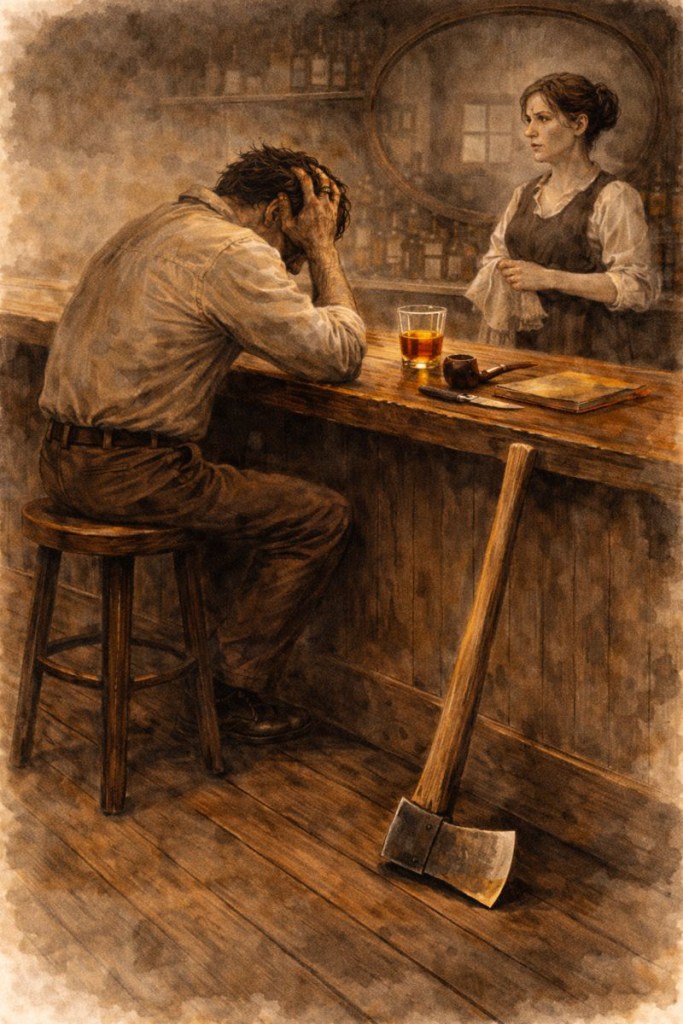

Eliza was giving the bar a wipe-down and laying out bar towels. She stopped at the sight of Burns with his axe, which he leaned against the bar as he drew up a stool. He swivelled away from her to the left, craning his neck as if to get a view out the window.

“Give us a brandy, love, would you? I’m parched.”

He took out his pipe and a plug of tobacco, which he cut with a pocket-knife.

She watched his hands tremble as he inserted the weed and lit the pipe.

“No brandy,” she said. Expression gormless.

He looked up, and the pocket-knife, slipping from his fingers, clattered on the top of the bar.

“For God’s sake.” Tone miserable in frustration. His head throbbed and his throat was dry. His heart thumped and fluttered alternately beneath his ribs, and the nausea set in. He took in some short, quick breaths to quell it, and bent forward, lowering his forehead into his hands. “Greed,” he moaned, “all greed. They’ve got it all but that’s nothing to them if they don’t ruin life for their neighbour as well. Rotten mongrels, and the coppers are even worse.”

Eliza, who had seen much of what there is to see in life, was not discomfited by his demonstration, any more than she had been by his leering the day before. Truth to tell, she didn’t mind the flattery. Perhaps, she thought, he misunderstood her meaning.

“Bit early, ain’t it? Delivery ain’t come in. Only got whisky.”

She poured him a nobbler as he fumbled in his pocket for some coin.

“Down the hatch.” He threw it back. “And another.” He sat and pondered for a while, smoking his pipe, staring out the window.

She went back to racking glasses and straightening the towels. He held up his hands to examine them. The whisky had quieted the tremors.

“Got a grindstone here?” he said.

“What?” Warily, anticipating a lewd jest.

“A grindstone for my axe. Got a grindstone on the place?”

“Nothing of the sort,” she said.

“Any grub or suchlike?”

“What would you think, at this time?”

“Well, give us a half bottle of whisky. You got that, don’t you? When I don’t have anything to eat, I have something to drink.”

He slapped the money down on the bar and drew his hands up in a solemn, conjurer’s flourish, or one like a monarch’s, bestowing jewels and baubles of gold on the greedy.

She watched him rise, pocket his bottle, shoulder his axe, and swagger out the back way.

“Well, I’m off to cut wood, at any rate.”

Next day, hair slicked down, on the way to the town hall he was afflicted with the shakes again. They told him downstairs to see Mr Franklin, who would know what he was talking about, so he groped his way up the staircase to the shire offices on the second floor, pausing halfway up to catch his breath, white-knuckled, supporting himself by the banister. Locating the door of John Henry Franklin, Esquire, Secretary, Stawell Shire Council, he knocked and was summoned in. He gathered himself, and again the call came.

Burns stood swaying in the doorway for a full half-minute as light from the window behind Franklin washed him out to a silhouette. The room smelled of stale ink and hot dust; a blowfly buzzed against the windowpane.

“My goodness, Burns, what is the matter with you?”

Franklin sat there, amazed at the gaze that met his: maniacal, animalistic, uncomprehending. He recognised the man from a meeting six months back, over some piece of council business so trivial he could scarcely recall it.

“Look at you, fellow, you’re tremulous. Have a seat before you fall down. What’s the matter with you? What are you doing here in a state like this? Confound me, you smell like a brewery. What brings you here, then?”

Burns shook all over in a spasm before regaining the power of speech.

“I have been on a drinking spree, sir, in my own time. Being once more sober, I have come here to …” momentarily forgetting why “… to look for work on the railway.”

Franklin stared at the long, fresh graze that ran along Burns’s left cheek, which his beard did not conceal. The man was swaying in his chair.

“You are serious.”

“I am a simple railway man, sir.” Your bloody highness. “Except for honest fellows like I the locomotives would not run … I seek nothing more than honest toil. I vacated my position at Dimboola because … it’s too far to go … I tire of the scenery … Heard there is some maintenance available in the more local vicinity.”

“I don’t think,” Franklin said, “there will be any chance of anything, at least until after the Christmas holidays.”

Burns nodded slowly for an inordinate amount of time.

“There is also the matter of the land I made inquiries about some months ago.”

Franklin was prompted to recall the substance of their previous meeting.

“There is no land available for selection,” he said firmly, and at that, Burns stood up, pulled himself together, and went away without another word.

Three days after the Scarlet Robin and her flock had castigated him for creating such a commotion in the peaceful bush, Burns walked into a scrappy little farm at Pimpinio, eight miles the other side of Horsham, owned by a German named Baum. Passing the barn on his way to the house, he was assailed from behind:

“The blokes you run into when you don’t have a gun.”

He started and froze, his heart doing its new jig.

“Mate, don’t get a shock.”

Burns knew him as well as anything, just couldn’t place the face at first, here in this dump.

“John, mate, from Avanel!”

“Yeah, I know, Putney. Couldn’t place you out of the blue like that. Well I’ll be bushed. How are you, you scallywag?” Navvy who’d worked beside them on the rail.

“Pretty good, mate. Just been doing a bit of graft for Baum, old tightwad he is. Say, what are you up to? Haven’t seen you and Charley since … must be more than a month ago on the line between Dimboola and Horsham, before I chucked it in.”

“Ah, I’ve been up in the country selecting land. Thought I’d drop in on the way home and see if old Baum had anything for me to do.”

“Well, I reckon you might be out of luck. Said he’s flat-out paying me. How’s the other bearded wonder, then, old Charley? Thought youse two were joined at the hip.”

Think, think. Could kill two birds here.

“Ah, haven’t seen him for a while, the bastard.” Think quick. “Wouldn’t believe the strife he’s put me through with the grog, so I left him out at Natimuk. Got on the spree, he did, as usual. Pawned his watch and I had to release it for him. Thanks to that I’m a broker. Look here, you wouldn’t happen to have a bit of tin on you, would you? I’ll be good for it next time I run into you, or I’ll bring it to you here or Avenel, whichever you wish.”

“Barely got enough left to go for a drink tonight. Baum can’t pay me till next week. Well, I can spare you a couple of bob, I suppose.”

“Thanks mate. Well, damn Baum anyway, I’m off home.”

Late in the summer, he re-adapted to an itinerant lifestyle without his mate, travelling by rail here and there about the Wimmera, catching a few days’ work when he felt like it. Life’s not too bad with a few quid in the bank. “No sign of Charley,” he thought from time to time. “That’s all well and good. Passable life, that of the solitary rambler, well and good.”

Three weeks after the Scarlet Robin, on a brilliant sunny day at Murtoa racetrack, he won a few bob on a skinny bush nag. Turned to leave the bookmaker and found himself face-to-face with Archibald Fletcher, the cow that Scotty, the idiot, had a run-in with at Glenorchy. Asked him what he won on, but Burns declined to reply, raising his lip as he brushed by him.

“Where is your mate?” said Fletcher behind him.

The same thing Fergus asked him the other day, when he’d run into him getting off the train at Stawell, peeved about all that money nonsense: “Here, I’d like a word with you. Where’s your mate?” “Oh, up there,” he’d said back to him, waving his arm, indicating vaguely – somewhere between Horsham, up the line, or that place upstairs, if such a one existed – as he escaped through the wicket.

“None of your business.” This time to Fletcher, and kept going, just the same as the other day.

He sat down in the refreshment tent with a beer and picked up a copy of the Ballarat Star, a few days old, lying on the wicker table.

He let the beer sit while he read:

Awful Discovery in the Wimmera Scrub.

A labourer working near Deep Lead, close to five miles from Stawell, yesterday discovered a man’s body in the bush – naked and without a head. Police have given no word on identity.…

The heart started its antics again. How fleeting, fortune’s favours.

“What’s up, mate? See you done all right in the third there.” Michael Carrick, city bloke, now working with him on a place outside Murtoa, joined him with a beer. Thoughts and hideous images swamped Burns’s skull in such a torrent they confounded the brain and the tongue.

“Nasty business that one, eh?” Carrick nodded at the paper.

“They’ll never find the head,” Burns said.

“What?”

“They’ll never find the head. Or the man who did it.”

“Daresay. When you think of it, I suppose that’s why the head’s not there. Means the culprit knew him. Yeah, of course. If they could identify the dead bloke, they’d go around looking at everyone who knew him. Still, with dogs and all …”

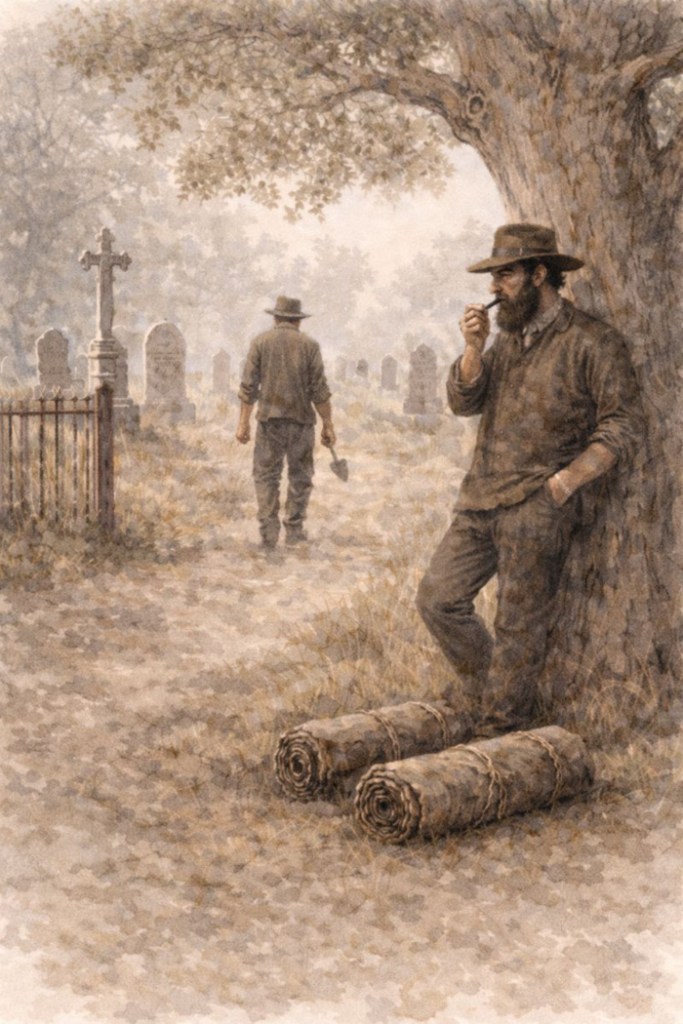

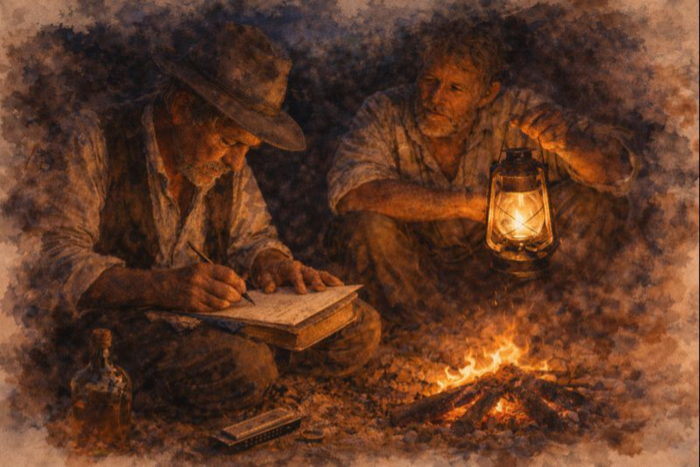

That night, back at their campfire, Burns, carrying a gas lamp and a fountain pen and paper, interrupted Carrick playing “The Flooers o the Forest” on his battered harmonica to ask him a favour. Carrick being possessed of the finer, more legible hand, would he mind penning a letter for him? He wanted it written for a man named Charles Forbes, who was working at Minyip and did not want the man to whom the letter was going to know his handwriting. It was for a man named Fergus, who owned a hotel in Stawell.

Good-natured Carrick saw no reason why not, and thought it was something he could do for his new mate. He shrugged and got a book out of his tent, on which to lay one of the sheets of paper.

Burns dictated the following letter, and the next day had another man drop it at the post office when he was in town:

Minyip, Jan 20, 1882

Dear Fergus – I wish to let you know that I am here with a farmer at Minyip at six shillings a day harvesting. I will send you down £5 to redeem my watch which I pledged before I left Stawell. I owe Burns £4 8s 6d cash. I gave him the ticket of my watch as a guarantee for his money, so if you pay the balance of the money to Burns and let Burns redeem the watch, as I got three pounds on it. By you doing so you will much oblige.

Do not answer this until I send you the £5. It is better for me to send for the watch than to drink it. I hope I will keep sober this time until I go to Stawell to you.

Charles Forbes, Minyip

Burns went down to the races again on the twenty-third of February, and asked a few of the bookmakers and drunks whether they’d run into Scotty, because he wanted the twenty quid he owed him. That night, he got drunk, created a disturbance at the Murtoa pub, and was arrested and taken to the lockup. When the watchkeeper arrived in the morning and heard the prisoner pacing and muttering inside the lockup cell, he paused at the door. With a jingle of keys, he unlocked it and pushed it open.

“What am I here for? What have I done?” Burns moaned, gasping and in a lather, his shirt soaked with sweat.

“Calm yourself, sonny boy, or else you won’t be goin’ nowhere for a while,” the watchkeeper growled threateningly, unimpressed at being assailed with such agitated queries.

“Why am I here?” Burns in peril of hyperventilating. “What is the charge against me?”

“You’ve been a naughty boy, that’s why. A very naughty boy.”

Burns stopped breathing and chilled to the bone, a frozen lump of nausea lodged in the pit of his stomach.

“Hauled in for being drunk and disorderly and causing a ruckus in this peaceable borough of Murtoa.”

Hearing these words, Burns’s countenance changed immediately, and apparently in token of relief and joy, he whooped and danced a lurching, deranged hornpipe in front of his captor.

From the draft novel Stawell Bardo © Michael Guest 2026