In her letter Jesse does not describe or elaborate on her dire predicament. It is only following the arrival of Larchmont’s brother, Harry, back in Paris for all to be revealed in personal dialogue between the two. Given the generous insights of our narrator, our good readers may hazard a guess at what has occurred to precipitate this action on Jesse’s part. After all she is the seventeen-year-old ward of Frank Larchmont, she and her fortune under his guardianship as according to her late father’s will.

Today, given the wealth Jessie is due to inherit on coming of age, in the absence of finaglers like Montez, one might expect her to live a relatively charmed life, however in her time there was what was known as coverture. Although Jessie’s life has been one of privilege, in terms of education and living conditions compared to the oppressive circumstances surrounding most women of the period (see Johnson, Edwards), she cannot remove herself from the legal constraints placed upon the rights of all women.

At the Women’s Rights Convention in Senneca Falls, New York in 1848, Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902) delivered her Declaration of Sentiments, a large part of which protested against coverture, the legal doctrine that treated a married woman’s possessions, wages, body and children as property of her husband, available for him to use as he pleased. Coverture gave husbands total control—from finances and place of residency to wife-beating and marital rape (Edwards).

Having deprived her of this first right of a citizen, the elective franchise, thereby leaving her without representation in the halls of legislation, he has oppressed her on all sides. He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead. He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns.

Excerpt from “Declaration of Sentiments” —Stanton

Conflicts, and obstacles to be overcome, are requisites of any good story. Gunter has been working toward the end of this story arc, engineering through character definition, and events related for the reader, the abrasive, but decisive interaction that is to occur between the brothers, Larchmont. As a playwright, dialogue is Gunter’s stock in trade, and the spoken word, over an author’s exposition, communicates a direct, if sometimes false, truth, for the reader’s evaluation. Although the words exchanged are personal, the author’s intention to implement a theme of American vs European is transparent.

The question a reader of our time might ask is why has he been setting up this nationalistic clash of cultures via two brothers, why should this appeal to the readers of his time? It is 1887, over a hundred years since the US gained independence, yet it appears the people are still defensive enough in regard to their global identity to appreciate jingoistic expression. Or perhaps, as today with extensive American coverage of the travails of Prince Harry and Megan Markle’s romance, Prince Charles and the terrible plight of Princess Diana, or the delightful children of Prince William and Duchess Catherine, there is a proportion of the American public that continue to be so enamored and fascinated with European culture and royalty to warrant chastisement.

Ironically, using Jesse’s ‘chevalier’, as she has called Harry, or knight, fashioned to ennoble and set right American values, Gunter relies on a trope of European origin.

CHAPTER 7

“NO! BY ETERNAL JUSTICE!”

The words are blotted with tears, and the whole appearance of the epistle is such as to give the young man a shock. He throws this off, however, remarking to himself, “Pshaw! She’s only a child in short dresses yet! I presume she must have been naughty. Even if she has been disobedient she needn’t fear Frank, he is gentleness itself to her.” But this evasive kind of reasoning does not suit him. After communing with himself fifteen minutes the action of the man comes into play. He was dawdling by the Rhine. He dawdles no more. And in one hour afterwards he is en route to Paris, as fast as an express train can take him.

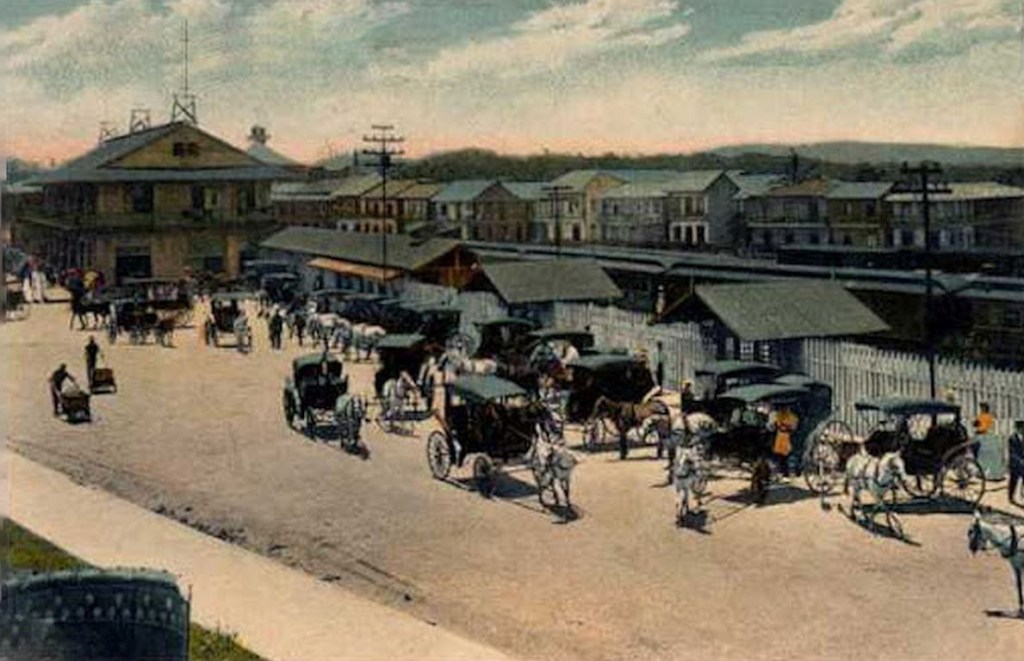

Arriving there next day, he goes over from the Gare du Nord, as fast as a fiacre can take him, to the pretty little villa on the Boulevard Malesherbes.

“Ah, Monsieur Henri, you have come back from Germany,” says the footman, opening the door, a grin of welcome upon his Breton face, for this young gentleman has endeared himself to the servitor by many fees.

“Yes, you need not mention the matter to my brother, if he’s at home,” says Mr. Larchmont, “but I presume he is out?”

“I think he is at the Bourse.”

“At the Bourse? That is rather astonishing.”

“Oh, he goes there every day, now,” answers the man.

“The dickens!” ejaculates Mr. Harry, and this information would set him wondering, did not another idea fill his mind. He says: “Step upstairs, please, Robert, and tell Miss Jessie that I am here, and would like to see her.”

“Mademoiselle Jessie is at her lessons,” replies the footman, “and I don’t think the governess cares to have her disturbed.”

“Never mind about the studies, Robert, I have only a few hours to stay in Paris. Just show me up to the school room, and I will break in upon the lessons, and help her with them,” returns Mr. Harry, and walks up to find Miss Jessie and get a surprise.

As he opens the schoolroom door and looks in upon her she is prettier than ever, but not wearing out her blue eyes over books, though there is a troubled look in them. She springs up with a cry of joy, and, as he gazes at her, he notes that during his few days’ absence an occult change seems to have come over the girl. Her short skirts had seemed to him her proper costume; now as she glides toward him they appear too juvenile.

She utters a warning “Sh-h-h!” and puts a taper finger to her lips, then whispers: “My governess is in the next room. She thinks I am studying, but I was thinking—thinking;” next gasps, “Harry! Dear good Harry! God bless you for coming to me!” and the pathos in her manner, and look in her eye, tell him that a great trouble has come into this child’s life.

“I am here,” he says, astonished at the girl’s manner, “to do anything you wish, Jessie; but it seems to me you should have applied to my brother, who is your guardian, before coming to me.”

“It is he who makes me come to you!”

“My brother?”

“Yes! Your awful brother is using his authority as my guardian. After the horrid manner of the French, he has betrothed me.”

“Be—betrothed you?” stammers the young man shortly in intense surprise.

“Yes, to that odious Baron Montez!”

“What, that old stockjobber? He’s twice your age! You are but a child.”

“I am seventeen, and, in spite of training, an American seventeen; and that is old enough to know that I never will marry Baron Montez!” cries Miss Jessie, angry at the suggestion of youth, more angry at the thought of Montez.

“Oh, ho, you love another!” laughs the young man, who tries to take this matter quite easily before the ward, though great indignation has come to him against the guardian.

“No, I love no one! I hate everyone. Rather than marry Fernando Montez,” falters the girl, her lips growing pouting and trembling, “I’d sooner go into a convent.”

Whereupon the gentleman says, in offhand manner: “Pooh! Pooh! No convent for such a beauty as yours.”

“And you will save me, even though your brother uses his authority as my guardian?”

“Certainly!” says the young man.

“Swear it!”

“Very well, you have my promise,” returns Harry who is loath to take the affair seriously; “but I don’t think you need have troubled me. Had you spoken to my brother, he would have most assuredly not tried to coerce your inclination in such a matter.”

But here Jessie’s words bring astonishment, disgust, and displeasure against the man he calls brother, to the gentleman facing the excited girl. She whispers: “I have told your brother! I have told him that I loathed, I detested, I hated the man he wished me to marry!”

“And he did not listen to you?”

“No! He said it was absurd for me to rebel against his lawful authority. That I must, and I should, do what he told me.”

“He did, did he? Then hang him! I swear you shall not!” cries the young man, for something in Jessie’s manner tells him she is speaking from her heart. “You shall only marry the man you want to!”

So he leaves the young lady reassured, and strolls over into the Parc Monceau (his brother not having returned from the Bourse), and communes with himself in the exquisite little pleasure ground, looking at the beautiful naumachie and rock grotto, and would reflectively toss stones into the lake, did not a gend’arme restrain him.

And all the time his eyes grow more determined, and the indignation in his heart against his brother increases.

Then he strolls back to the house, and Mr. Francois Larchmont being at home, walks into that gentleman’s library, with a very nasty look upon his countenance.

“You here?” says Frank, starting up with unnerved face. “This is a surprise!”

“Yes,” says the other nonchalantly. “In Cologne I received a letter from Miss Severn—I suppose we must call her Miss Severn, since you consider her old enough to marry. By the by, I think you had better have her governess put her in long skirts; she’s been growing lately.”

While he has said this, notwithstanding Harry’s manner, Frank’s face has become white. He suddenly asks: “Did that stop your journey?”

“Certainly! An appeal from a woman would stop any man’s journey. I have seen your ward. She tells me what I find it very hard to believe—that you wish to exercise your authority as her guardian, to coerce her into marrying this South-American stock-jobber, and gambler—Baron Fernando Montez. Is it true?”

“It is,” falters the other. “I wish her to marry him!” Then he goes on suddenly, noting the look of disgust upon his brother’s face, “Don’t misunderstand me, Henri, it is necessary. She has now arrived at the age when it is best for her—for any young woman—to enter the world; and to do that in France, it is necessary for her to take a husband.”

“But not such a husband.”

“He will give her title.”

“Pooh! titles are common here.”

“He will accept her—and this is the important part of the matter—without a dot.”

“Without a dot? Why, she is worth a million dollars in her own right.”

“Nevertheless she will have no dot!”

“What do you mean?” gasps the other.

Then Frank bursts out hurriedly: “Don’t look at me so. I have lost Jessie’s money in speculation.”

“Then you must make it up out of your own fortune. You are a very rich man!”

“I was.”

“Good heavens! have you lost that also?”

“Yes, it is involved. At present I could not, if called upon, hand over Miss Severn’s fortune, which was entrusted to me by her father’s will, when I gave her to her husband. In France it would be demanded at once, if anyone else except Baron Montez married her.”

“And you have lost all this money—in what?”

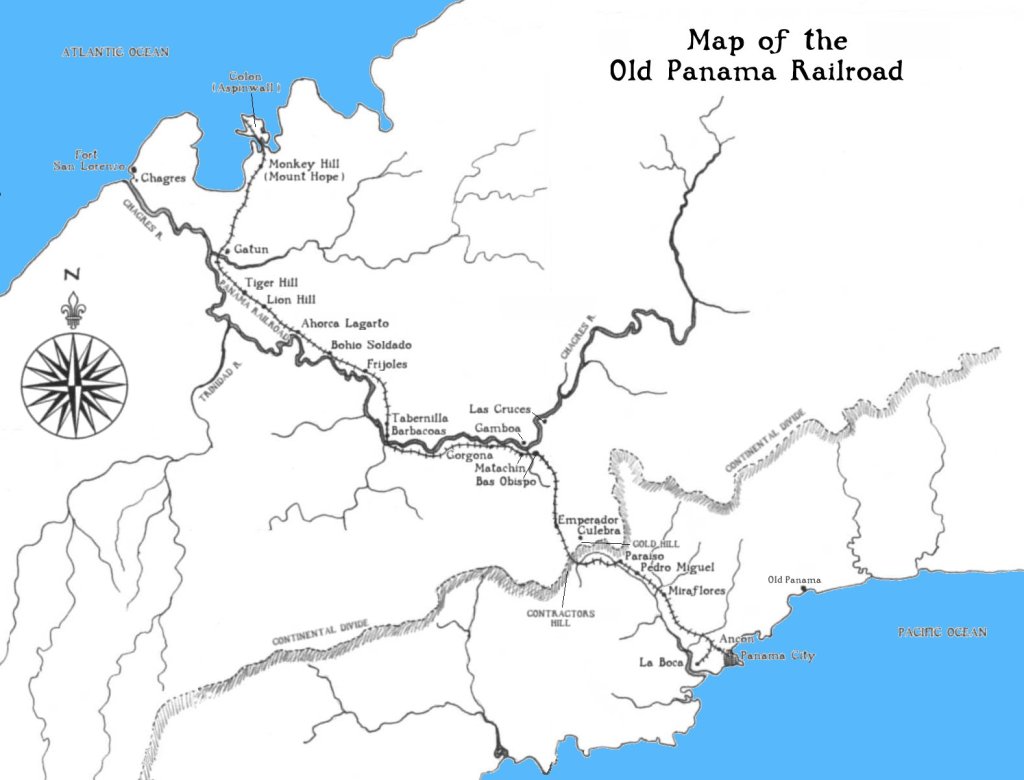

“In the shares of the Panama Canal, I think.”

“In the Panama Canal, you think?” sneers Harry. Then he scoffs: “You—you are the only American who has not made money out of that giant fraud? You are so afraid of being thought a man of business, that you have let that swindling South American make you bankrupt?”

“I—I do not know—my affairs are involved. I have entered into so many speculations with Baron Montez.”

“Ah, he has your money!” cries the New Yorker.” He has Miss Severn’s money. He has got the dot before. Now he will take the bride, generous man, without it, but she shall not marry him! I have sworn it!”

“Great heavens! You would ruin me!”

“I would ruin everyone to save this girl’s happiness!”

“You—you love Jessie?” gasps Frank with twitching lips.

“As a brother! That is all. But it is well enough to see she is not wronged by you!”

“You forget I am her guardian!”

“And I am her protector! She shall not marry Baron Montez! I’ll prevent it with my fortune—with my life! Do you suppose I will stand by and see a lovely, beautiful, young American girl sacrificed on the altar of your speculations? No! By eternal justice!”

“You will save her?” asks Francois Leroy Larchmont, a curious wistful look coming into his uncertain eyes.

“Yes!”

“God bless you!” cries the man, and sinks down into a chair, sobs in his voice, but no tears in his eyes.

“Why do you thank me for saving her from your friend?”

“He is not my friend! I hate him! I fear him! I loathe him now, but I am in his power! But thank God! Henri,” and the weak man has seized his brother’s hand and wrung it, and is muttering to him: “Thank God! you will save her—save her from marrying him—save her for me—for me—I love her!”

“Not for you!” cries the other, breaking away from his brother’s grasp, and an awful contempt coming into his soul. “You are not worthy of her. You love no one but yourself, and that not well enough to fight for your own hopes, desires or loves! When you renounced your country, you gave up manhood! But I’ll save her for some good American!”

With that he leaves his brother, who has sunk down, and is cowering away from Harry Larchmont’s indignant eyes, and goes up to again see the lovely girl her guardian’s weakness would have sacrificed, and tells her to be of good cheer, that he will save her. “Only one thing—procrastinate this matter,” he adds. Then he queries wistfully, “Can you be woman enough to procrastinate? Are you still a child?”

“Why not defy him? With you by my side I’ll snap my fingers in Montez’ face.”

“That,” says the young man, wincing a little, “will require a sacrifice from me.” For he knows, if matters come to a climax now, to give this girl her fortune and keep his brother’s name in honor before the world, will sadly cripple his means and make him comparatively poor.

Looking in his face the girl says suddenly: “No, I see it is important. I am not child enough to ask too much. I will do as you say.”

“In every way?”

“In every way.”

“Then procrastinate. Get my brother to bring you over to New York for this winter; put off the wedding till the spring—till the autumn. If Frank demurs, tell him you will write to me, and that will settle the affair, I think.”

“You—you are going away?” falters the child, growing pale at the thought of his desertion.

“Yes, I am going away.”

“Why?”

“To save you.”

“How?”

“To find out more about this man, who has my brother in his power—this Baron Montez of Panama and Paris. Here he is surrounded by all the Panama clique; there is no rent in his armor that I, an American, unaccustomed to the ways of Paris, can pierce. If he has a flaw in his cuirass, it is at the other end of the route. I am going to Panama. Please God, I’ll nail him there! I leave this evening for England. Then to New York, to arrange several matters of business, for if the worst comes to the worst—”

“You will permit me to be sacrificed?”

“Never! It is for that I go to New York.”

“But if the worst comes to the worst, you—”

“It is for that reason that I go to New York. Don’t ask me questions. Only know that I am forever your protector. What my brother has forgotten, I will do; his dishonor shall be effaced by me.”

“His dishonor!” cries the girl. “What do you mean?”

“Nothing that I can tell you; but good-by, Jessie. Be sure of one thing—that you need never marry Baron Montez of Panama!”

“God bless you!” cries the girl, and gives him the first kiss she has ever given him in her life. But it is the kiss of the child, not of the woman. The kiss of gratitude—the kiss that beauty gives to the knight that risks his life to save her from the giant Despair.

Twenty-four hours after, Harry Larchmont sailed for New York on the Etruria, and a month later his brother brought his ward to America upon the Gallia; but Baron Montez said to him, “Remember, mon ami, you must bring her back by Easter. Springtime in France will suit Mademoiselle Jessie’s beauty.”

Four weeks after the Larchmonts arrive in New York a letter comes to Fernando, from a co-laborer of his in the Panama scheme, one Herr Alsatius Wernig, who is in America on some joint business, and will shortly proceed to the Isthmus.

This epistle contains some curious news about the Larchmonts.

After reading it the Baron’s face grows grave for a moment, then it suddenly lights up. Montez, with a jeering smile, exclaims: “What? That idiot who plays football and takes the chance of being killed for fun!” A moment later he remarks meditatively: “There is always danger in a lunatic!” and an hour afterwards sends a carefully prepared cablegram to Herr Alsatius Wernig in New York.

Notes and References

- trope: “a recurring theme or motif, as in literature or art: e.g. the trope of motherhood; the heroic trope. A convention or device that establishes a predictable or stereotypical representation of a character, setting, or scenario in a creative work” (dictionary.com).

- fiacre: “a small four-wheeled carriage for public hire” (lexico.com).

- stockjobber: “a stockbroker, esp one dealing in worthless securities” (Collins).

- naumachie: an artificial lake, orig. used for mock sea battles for entertainment.

- without a dot: colloquial—less than nothing—zilch, nada.

- cuirass: “a piece of armour consisting of breastplate and backplate fastened together” (OED).

Accampo, E.A., Rachel G. Fuchs and Mary Lynn Stewart (eds.), Gender and Politics of Social Reform in France (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995).

Edwards, Rebecca: Early Women’s Rights Activists Wanted Much More than Suffrage. history.com, 2028. Jump to Article

Johnson, Julie Anne: Conflicted Selves: Women, Art & Paris 1880-1914. PhD Thesis, Queen’s University

Kingston, Ontario, Canada, 2008. Jump to file

Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, “Declaration of Sentiments” address, Seneca Falls, New York, 1848. Jump to Transcript

Tilly, Louise and Joan Scott, Women, Women, Work, and Family (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1978)

This edition © 2021 Furin Chime, Brian Armour