Trying to get a desperate message through to possibly avoid a looming disaster, a dangerous journey through a dark expanse. Where had I heard that before? It was also in Germany, but not in the Black Forest.

This particular journey started from an airfield just outside Munich. The dark expanse was the North Sea, the destination Dungavel Castle in Scotland, strangely reminiscent of Dunwolf, but purely coincidentally. It was the Duke of Hamilton the desperate messenger had tried to reach, a fellow aviator, and one he had hoped could pass his message on to Churchill. Avoiding being shot down, he had to parachute into a field, unable to find his intended destination.

The messenger was a man I had never met or had any interest whatsoever in meeting, but whose presence I had been aware of while living in West Berlin. He was the sole occupant of an entire prison built to incarcerate six hundred, kept there incommunicado, lest he told of what his errand had really been about. In later years, when his son was finally allowed to visit, guards were always present and he was not permitted to discuss anything in relation to his mission. Don’t you wonder why?

Spandau Prison was less than twenty kilometres from where I lived, but normally, nobody was allowed to enter. An absurdly expensive, huge place to house the desperate messenger, already pushing ninety in the early 1980s, kept there under the jurisdiction of the Allied Command. These days they say it was the Soviets who held him, but when I was in West Berlin, we knew it was the British who blocked any attempts for release, even by someone as influential and definitely acting out of compassion and not because of any pro-Nazi sentiments, as former Mayor of West Berlin and Chancellor of Germany, Willy Brandt. But why?

It was because of what Rudolf Hess knew about his mission, which was still highly embarrassing to the British. Had there been an intelligence sting to convince Hitler that Great Britain had been seeking a way out of the war? Or was Hess simply a madman? Berliners need knew of the old man, held alone in that huge and foreboding prison. Did he deserve to be there? At one time, probably. He had been Hitler’s deputy, had signed into law terrible policies that harmed and killed so many. Not an innocent, by any means.

Why on Earth had he tried to get a message to Churchill? Because he knew that madman Hitler was about to invade the Soviet Union and thereby open a second front making the war unwinnable for Nazi Germany? Or had he been acting on the direct orders of Hitler, in response to secret British overtures? The murky world of intelligence services conceals many such plots. We will never know the details of this one, but we can be thankful that his desperate mission to find peace with the UK and avoid the defeat Nazi Germany did not succeed, whatever the circumstances.

Hess allegedly hanged himself in 1987, at the age of 93. A messenger, whose to some still immensely embarrassing message finally “had to be stopped” from being told, because more moves were afoot to finally release the old man? Will Ernest von Linden succeed in getting his message through to King Leopold, or will he too be incarcerated or even killed?

CHAPTER 6

WAYLAID

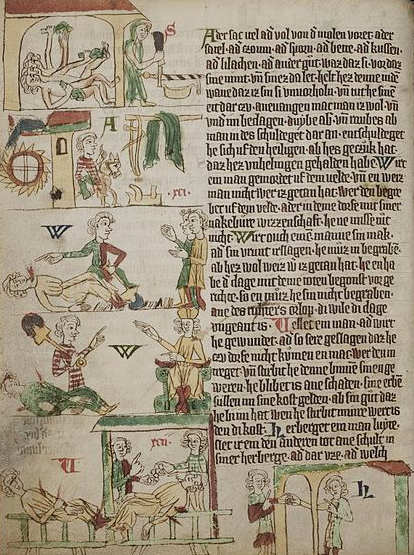

The baroness and Electra were ready to sit with Ernest at the breakfast table, so that no time might be lost in consultation. The distance to Baden-Baden was fifty miles — the road exceedingly mountainous and rough. If he could make the journey in a day he would do well. At all events, the chances were that he would be obliged to be gone three days, as he could not expect to find time for business on the day of his journeying.

His business, however, was easily understood, most of it being left to his own judgment. Since Sir Pascal Dunwolf had made his appearance at the castle the baroness could not believe that the grand duke would insist upon his marriage with her daughter when the facts of the case had been presented to him. She knew how eager the dukes were that the great estates of the grand duchy should be possessed by their chief henchmen. She knew that during the reign of Leopold’s father three orphan daughters of wealthy baronies, representing their respective families, had been forced to wed with husbands of his choosing; and one of them, at least, she well knew had at the time a lover in the lower order of society to whom she was devotedly attached.

Still, her case, she felt, was different. Her daughter had been long affianced — allianced, too, by a father who had given his life to the state — to a youth of noble lineage and owner of a large estate. As she arrived at this point in her statement Ernest interrupted her, saying:

“And for that very reason, I am informed the grand duke said, he objected to our union; perhaps not in so many words, but such was doubtless his meaning. He regards the Barony of Deckendorf as already powerful enough. Let the earldom of Linden be combined therewith, as would be the case in my marriage with my darling, and Leopold thinks the lordship might, in time, over-shadow his own proud station.”

“O! what a fool!” exclaimed Electa, impatiently. ”When Ernest and I would be to him two of the very best and truest of friends.”

“That is what I shall try to make him understand, my own precious love,” said Ernest, as he moved back his chair from the table. There was further conversation on the all-important subject, but, as the result will be seen in the end, there is no need that we should follow it further.

The question of companionship on the journey had been discussed, and the brave youth had decided that he would go unattended. He was not afraid of robbers, for he took with him nothing for them to steal. As for money, all he could want was in the hands of the baroness’s banker in Baden-Baden, and a simple cheque would command it. A companion of his own turn of mind and thought, one intelligent and educated, would have been pleasant; but none such was within call; so, after due consideration, he had resolved to go alone. Thus he could speed on his way as he pleased, and enjoy his own thoughts and fancies.

The baroness had given her last words of direction and caution; both she and Electra had given him their blessing, and their parting kiss; after which he sent a servant to order his horse, while he went to his chamber to get his portmanteau and his pistols.

The pistols, of the very latest pattern, procured of the manufacturer, at Heidelberg, less than a year ago, were the best weapons of their class to be found anywhere. The spring jaws for the flint, with the steel for the stroke directly over, and closing the pan, had been introduced; and the stock had been brought to a graceful, compact, and convenient form. In short, the pistols which our hero then handled were as nearly perfect as was possible with the flint lock.

Those for the holsters were large and strong, carrying an ounce ball, the handles, or buts, being heavily bound with cast brass, to fit them for clubbing purposes in case of need. The smaller pistol, for the pocket, was highly ornamented. There were two barrels and two locks; the bores little more than half the diameter of the former; its sandalwood stock being richly bound and inlaid with silver and gold.

As he took them up he instinctively opened the pans to see that the priming had not been accidently disturbed, and having found them intact, he put the smaller one into his pocket; took the others under his arm; then picked up his portmanteau and went out. In the passage he found a servant to whom he gave his key, bidding her to keep it until his return.

As he passed through the lower hall he looked round for any friendly face that might appear; but no one did he see. He had not expected that Electra would come down; he had bidden her not to do so; but she might have sent word. None came, however, and he went his way out through the vestibule, down the broad steps, to the inner court, where he found his horse, and near by it standing Sir Pascal Dunwolf.

For the moment his heart quickened its beatings, and his hands closed more tightly upon his luggage; but the knight gave him a smile, and offered his hand, which the youth took as soon as he had landed his portmanteau.

“You have my letters?”

“Yes Meinherr; and I will promptly deliver them.”

“Thanks! I was not sure that my page had given them to you. The graceless rascal is such a liar that I know not when to believe him. But he is faithful, nevertheless, and serves me well, when it comes convenient for him to do so. I wish you a pleasant journey, Captain; and I beg you to forget our little passage of yesterday.”

“It is already forgotten, Sir Pascal.”

“Thanks again; and once more — success to you.” And with this the knight bowed, at the same time, raising his plumed cap, and then turned away.

Ernest secured his portmanteau in its place, and put the pistols into the holsters; then vaulted to his saddle, and rode away. Not until he had crossed the draw-bridge, and began the descent of the deep ditch beyond, did he think of the last look he had seen upon the face of Sir Pascal Dunwolf. At that moment his thoughts chancing to turn back to his interview with the dark-browed knight, the look glared upon him. He saw it as though the face was there before him, and he could read its full diabolism. What did it mean? There had been malevolence in it, and such intense spite; but why should he have worn an expression of triumph? — for such it had surely been. Had he more promise from the grand duke than they had thought? Had he ground for the assurance that the youth’s mission would be fruitless? If not, whence his feeling of triumph? — for, the more he thought of it, the more deeply was he convinced that he had not been mistaken in his estimate of the knight’s look.

“Bah! — I am a fool!” he told himself, after a deal of perplexing study. “The man is a natural braggart, and his look of triumph was a reflection of the wish of his heart. The grand duke will never enforce the marriage of Electra von Deckendorf with that monster! I will make him understand that he will find a safer friend in me than any man can find in Sir Pascal Dunwolf.” And he resolved that he would think no more about it.

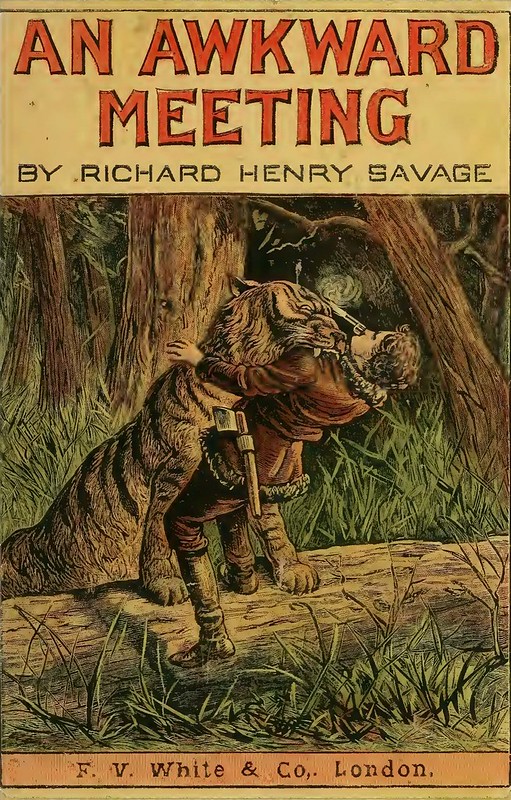

The sun was two hours high as Ernest crossed the stream in the valley, and shortly afterwards he began the ascent of the Schwarzwolf Mountain — or rather, of a spur thereof. It was a wild, rugged pass, but the path was clear, and he went on without difficulty, but rather slowly. At the summit of the spur the road lay through a dense growth of mountain fir — the black fir, whence the forest (wald) takes its name — and here, under the shadow of a precipitous cliff which arose on his left hand, he saw a large wolf sitting. His horse stopped suddenly and tried to turn, but the rider held him to his place; he could not hope to force him by the place, however, while the beast remained at his post; and he certainly exhibited no signs of moving out of the way.

The captain knew that sometimes an old wolf, in his mountain fastness, would be very bold and fearless, though he did not believe the animal would attack him. He considered a few moments, and then drew one of the large pistols, meaning to give the beast a shot between the eyes, the mark being direct to his aim. At the cocking and aiming of the piece the wolf raised himself to an erect posture, but nothing more. With a sure aim our rider pulled the trigger. A flash of the powder in the pan followed, and that was all. He waited a few seconds, to make sure that the fire had hot held only temporarily, and then knew that his pistol had missed fire entirely — something he had never before known with those weapons. Never before a burning of the priming without communicating fire to the charge.

The bright flash and the tiny wave of smoke that curled up from the pan caused the wolf to take himself off, but that mattered little to the owner of the pistol at that particular moment. He cared more to know what was the matter with his powder.

As soon as he had made sure that the wolf had disappeared, he slipped from his saddle, and having thrown the rein over the broken stub of a stout branch, he gave his attention to his pistol. First, however, before going further, he thought he would try the other. He took it from its holster, cocked it, took aim at a small sapling fifteen to twenty yards away, and pulled the trigger. Whew! The result was as before. His next movement was to draw the double-barrelled weapon from his pocket, and try first one hammer, and then the other; and, as the reader doubtless imagines, with the same result.

And now for the bottom facts. There must be mischief somewhere. Ernest sat down upon a stone by the wayside, and exposed the screw upon the tail of the rammer of one of the holster pistols, with which he easily drew forth the wadding of the first one he took in hand; but he quickly determined that it was not the wadding he had himself put there. It was a wad of paper, which he recognised to be a part of a leaf from one of the books that lay in his room. He went on, and drew forth another wad, but no bullet. Then another — and yet another — piece from the same book, until the barrel was empty and the vent-hole clear.

The second holster pistol, and likewise both the barrels of the smaller pistol, were found to have been deprived of their proper charges of powder and ball, and filled with nothing but paper from his devoted book! He sat for a time and looked at the three pistols.

And the light burst upon him. He now could translate the look he had seen upon Dunwolf’s dark visage. And he understood, also, the secret of the early visit of the hunchback page. And, of course, there was more to come, which would doubtless present itself in due time.

Fortunately he had plenty of ammunition in his saddle-bags. He opened them, and proceeded to load his weapons with extra care. He measured the powder critically; saw that the communication with the priming was free; he fitted a tallowed patch about the bullet so that it should drive home snugly; and when the work was done, and the flints had been made sure of striking plenty of fire, he put the pistols back into their places of rest, and resumed his journey.

At a short distance from where he had stopped he reached the brow of the spur, and looked down into the valley below. It was a vast concavity of the forest, black as night, with here and there a giant oak or pine towering above the levels of the firs, and anon a cliff of gray rock lifted its bare peak into sight. The path was lost to view not far away, but the traveller knew where it lay, and was well acquainted with its many windings and its numerous branches. It was the branching of diverging tracks that made the desolate portion of the Schwarzwald dangerous to strangers. Many a man has been lost in those endless, intricate wilds; the sun and stars shut out by the mountain mists: his instinct leading him onward — ever onward — in a fatal circle, which he pursues until fatigue and famine conquer, and he finally sinks, perhaps not an hour’s journey from the point of his departure!

But Ernest von Linden knew every turn and every branch, and he pushed surely on. A few hours’ more would bring him to the town of Wolfach, beyond which the road was broad and mostly good.

He had reached the foot of the mountain spur, and was striking into a broader and better path, when he distinctly heard the footfall of a horse other than his own, not far away on his left hand, and on looking in that direction, he detected an opening in the thick wood, which he soon discovered to be another path, joining that which he was following at a short distance ahead. He looked to it that the pistols were loose in their holsters, and a few moments later two horsemen appeared to view directly before him, and not more than a dozen yards away.

As he drew rein and brought his horse to a halt, the two men turned and faced him, and he recognised at sight two of the stout men-at-arms of Sir Pascal Dunwolf’s troop. They had not taken the trouble to disguise themselves.

“Ha, Captain! Is it really you? I’faith, you must have given Sir Pascal the slip. He declared in our hearing that you would not leave the castle. Do you journey to Baden-Baden?”

“Such is my intention.”

“Good! We shall have company. In these times, with Thorbrand’s infants running at will through the forest, it is just as well to travel in goodly company. But I am surprised that you should have come alone.”

“I have traversed this section many times,” the young man returned, and have yet to encounter an enemy. Still, as you suggest, we know not when one may appear.”

“That is even so; but against the three of us it would require a strong force to prevail.”

While this coloquy had been going on our hero had been making a study of the two men before him, and he had been content to quietly answer them that he might gain the opportunity.

They were men of powerful frames, with VILLAIN indelibly stamped upon both their faces. Those faces were coarse-featured and battered; heavy-lipped and low-browed; with as wicked a complement of eyes as ever looked from a human head. They wore the uniform of their troop, heavy swords hung at their sides, daggers in their girdles, and evidently pistols in their holsters.

Ernest knew that they must have left the castle during the night, for he remembered distinctly having seen them at parade on the preceding evening. And if they had left the castle during the night, of course their chief had sent them; for they could not have passed the sentinels otherwise. And for what had they been sent? Ah! it remained for them — clumsy loons! to blunder out the truth.

“Captain,” said the second man of the twain, with an exceedingly cunning look, “did the chief send any letters by you?”

What did this mean? Why was the question asked? The youth determined to pursue the matter to a solution.

“He did,” he answered, after only an instant’s hesitation.

“Oho! Then you saw him. I s’pose he gave the letters to you with his own hands.”

Ernest began to gain a glimmering of light.

“No,” he said. “They were given to me by another.”

“I wouldn’t have believed it. Generally he doesn’t trust his letters in the hands of his underlings. I s’pose he sent ’em by Lieutenant Franz?”

“No.”

“Eh? Who could it have been?”

“They were brought by a humpbacked dwarf, who brought them to me in my chamber before I had completed my toilet.”

“Well, is it possible? What d’you think of that, Roger?”

The man thus appealed to declared, most soberly, that he wouldn’t have believed it.

The rascals had now learned all they could hope to discover by questioning. They believed that the captain’s pistols were innocent of powder and ball; and he knew that they so believed. Further, he knew that Sir Pascal had sent them out to intercept — to waylay — him, and that he had promised them that their victim’s weapons should be rendered harmless.

At this point Ernest gathered in his slack rein and sat erect.

“Look, you, sirrah!” to the man who had first addressed him. “If I heard

correctly, your name is Roger. Now, sir” — to the other — “by what name may I call you?”

“My name is Otto, sir,” the fellow replied without hesitation

“Will you now tell me whither you are bound?”

“Why,” answered Roger, “we are going right along with you.”

“To Baden-Baden?”

“Certainly.”

“For what purpose?”

“Why — bless you — the governor sent us, of course.”

“Aye, but upon what business? He did not send you without a purpose.”

“No, certainly not. He sent us — Eh, Otto?”

“Why — he sent us,” said Otto, “to hunt up the trail of the robbers; and that was why we started off on that side path.”

“And now,” suggested Ernest, “you will look for them in Baden-Baden?”

“Yes; if we take a notion so to do. We are acting on our own judgment, and we’ll have you to know that we are not responsible to you.”

“Certainly not. I should be exceedingly sorry if you were. And now, Roger and Otto, you will turn your horses’ heads to the front, and ride on. I propose to ride in the rear.”

At that moment the assassins were evidently not prepared to act in concert; so without hesitation, save for the simple exchanging of a glance, they turned, as they had been ordered, and rode on. For a little time they sped on at a gallop, gaining a considerable distance in advance. At length they came to an open glade through which ran a brooklet of clear, sparkling water, where they reined up and allowed their horses to drink. Their heads were close together in earnest consultation, and our hero saw one of them point over his shoulder towards himself, at the same time laying the other hand upon the hilt of his sword.

Evidently the time of trial was at hand; but the brave youth did not shrink, nor did he fear. He felt that he had the advantage, and with a watchful, wary eye upon their every movement, he rode slowly on.

Notes and Reference

- barony: a baron’s domain.

- Schwarzwolf Mountain: fictional.

- fastness: stronghold; fortified place.

- rammer: in a muzzle-loaded firearm, an attachment to help load the bullet.

- tallowed: v.t. constructed from n. “tallow”: solid oil or fat of ruminant animals (Encyc. Brit. qtd. Century Dictionary).

- anon: soon.

Handwerk, Brian. “Will We Ever Know Why Nazi Leader Rudolf Hess Flew to Scotland in the Middle of World War II?” Smithsonian Magazine (May 2016).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.