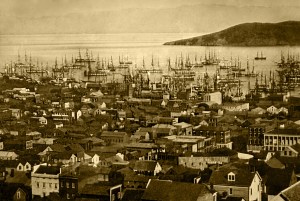

Twenty-five years after the closing events of the last chapter, Panama is still our setting, though the focus has shifted from the Panama Railroad to a new major engineering challenge: The Panama Canal. The year is 1880 and Ferdinand de Lesseps, French diplomat and developer of the Suez Canal and his entourage, are in Panama to celebrate commencement of the French undertaking to link the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

A New York reporter tries to obtain engineering information from the official party, and amid an ensuing scuffle, mention is made of the Monroe Doctrine. Instigated by John Quincy Adams, then US Secretary of State, and first delivered in a speech by President James Monroe in 1823, this policy became a formative statement in the international presence of the United States. It fundamentally and unilaterally opposed European colonialism in the Americas, or meddling “into any portion of this hemisphere” (Monroe). Most of the Latin American colonies had either gained independence from Portugal or Spain, or were on the point of doing so. Monroe stated that any European efforts to reestablish control would be seen as unfriendly toward the United States. The United States would, however, recognize existing European colonies.

The attitude of the United States towards France was quite positive at this time. France had helped America substantially in the Revolutionary War (1775–1783). A swathe of public opinion decried the “virulence” of the Paris Commune of 1871 (Bernstein); but a good relationship ensued with the Third Republic. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 massively increased the size of the United States, and enabled its continental completion. The Statue of Liberty, a gift from France, will be inaugurated in New York in 1886.

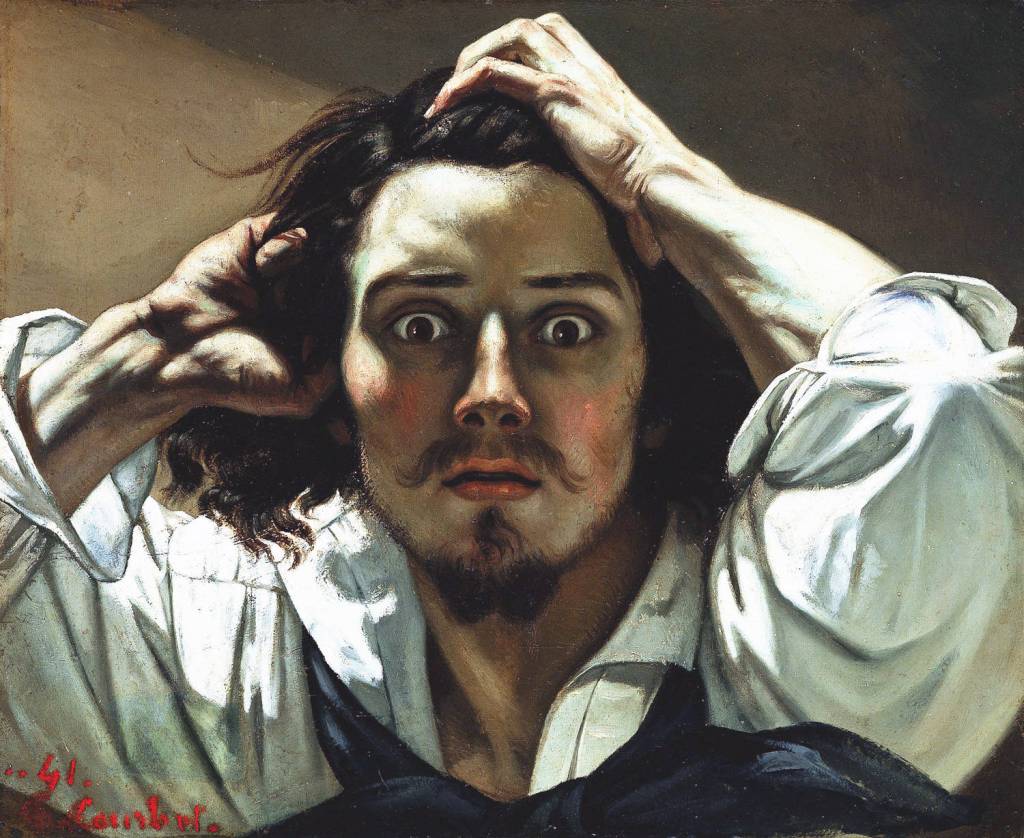

The narrator, we know, finds it difficult to keep a secret. If his insider knowledge of Montez, and his ‘book cover’ assessments of other characters are correct, we as readers have an idea what is going to happen, if all goes according to fomenting plan. Our narrator also, you will find, is not backward in coming forward over the plight of shareholder’s interests being neglected in the expensive promotions taking place—to the extent of shouting at the reader. The French attempt to create a canal was abandoned in 1887, a mere five years before this novel was published, and given the strident voice, it may not be far-fetched to suggest the author personally knew shareholders, or was one himself.

Not only did shareholders lose greatly in the $287M venture. As noted on the first page of the chapter, yellow fever is still prevalent, and over twenty thousand will die before it is over. One such sad case is the Director General of Works and Chief Engineer, Jules A. Dingler. He arrived in Panama in 1883, and spent $100,000 building a mansion, only to lose his wife, son and daughter to the disease.

The fate of his prize stallions is one of the heart-wrenching episodes of his tragedy:

His wife had frequently gone riding on one of two magnificent horses worth 25,000 francs, which had been a gift from Gadpaille [a labour recruiter] in Jamaica. After her death, the director did not wish to encounter anyone else on the streets of Panama riding these horses, so he ordered the beasts to be killed. The staff refused to carry out the command. Finally they found a poor fellow who was given the role of executioner, but at the last moment his hand trembled and he could not finish the job. For hours the horses were heard, partially disembowelled, screaming in agony. In the end they were shot dead.

Parker, p. 123

Dingler returned to France in 1885 a broken man and died within six months.

Under our narrator’s guidance, readers continue to follow the nefarious career of Fernando Gomez Montez, which is interlinked with the Panama Canal project. We hear no more, for the time being, of the fate of sweet Alice Ripley, or her daughter left alone in the United States. However, not content with the elevated position he has achieved, our conniving Montez has two new victims in his sights.

BOOK 2

The Franco American

CHAPTER 5

Black Blood Changes to Blue

It had been a day of triumph for Panama and le grand Français Ferdinand de Lesseps, this first day of January, 1880—this day that inaugurated the opening work of the Canal Transatlantique; that was to make the commerce of all oceans one; that was to wipe out from the sailor’s log the tempestuous icy hurricanes of Cape Horn, and the more languid but equally retarding calms of the Cape of Good Hope. By it France was to become richer, the world happier, and Ferdinand de Lesseps doubly immortal—this man of Suez and of Panama.

Five o’clock on the previous afternoon, welcomed by the braying of the one military band, and addresses from the Committee, and President of the State of Panama at the railway station, he had descended from the train bringing him from Aspinwall, soon to be rechristened Colon.

The bridge over the track of the Panama Railroad, from which the speeches were made, had been adorned with the flags of France and Colombia.

In carriages, the finest in the city, though not of the latest style, and the worse for twenty years’ wear, Comte de Lesseps and his attendant party of engineers, politicians and fortune seekers, had been driven through streets, that for once in the history of Panama, and only once in its past, present, or to come, were clean. They had been swept by municipal order, that their foul odors might not affront the delicate nostrils of the great Frenchman. Along the road from the railway station, leading up to the old Gargona road, and thence into the Plaza and the Grand Hotel, the huts and houses were especially white washed for the occasion, to destroy germs of yellow fever, or cholera Asiaticus that had convenient resting place upon their palm-thatched roofs and mouldy beams.

This had been the suggestion of Don Fernando Gomez Montez, by this time one of the leading dignitaries of the city, banker, rich man, and general swell, who had impressed his views upon his confrères, by this pertinent remark: “Caramba! If all those delicate Europeans encounter Yellow Jack and el vomito negro before they commence operations, good-by to our canal which is to make us rich.”

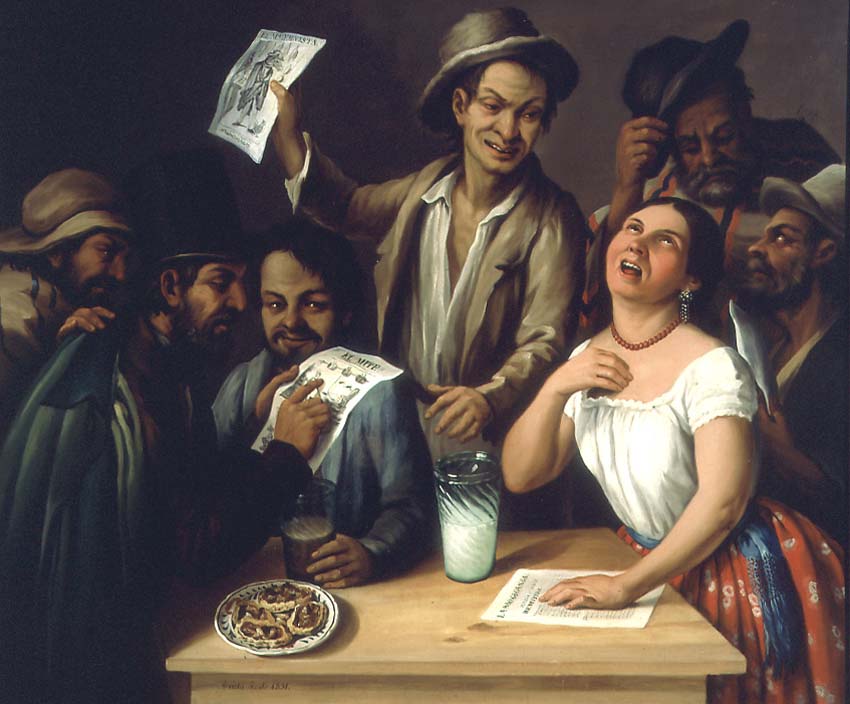

So the French party came with prancing of horses and shoutings from the crowd of creoles, negroes, and the general populace, between two battalions of native troops drawn up along the road, as ragged, as barefooted and as badly armed as in the days of ’49; for this man and his nation were to bring wealth, commerce, and enterprise to this city deserted since the days of the early Californian travel; and Panama was to become even greater, richer, and more populous and important than the old town whose deserted tower stands in tropical jungle five miles to the south—the one that Morgan’s buccaneers destroyed two hundred years before—the richest city of its size on earth.

Among the élite gathered to meet the great French man had stood Fernando Gomez Montez, apparently not much older than when he had made his first great coup in life from the returning Californian, since which time he has devoted the plundered gold dust of that night to commercial pursuits, and has built up for himself a fortune, large for a Colombian city, but not great for Paris or New York.

His poverty he has learned by travel, for he has been both to France and America; and his intellect, bright, wicked, and unscrupulous as ever, has been made subtile, cautious, and wary by experience. At twenty he was a great villain, at forty-four he is a great man, and therefore greater villain. To the audacity of the bandit he has added the finesse of the diplomat.

During the preceding day he has made his address at the railway station and at the banquet of the evening, and has been embraced by le grand Franc̗ais, and petted with diplomatic tact, and called the hero local of the canal—for he had greatly assisted in obtaining from the Colombian Government the concession about to be sold to French stockholders for ten million francs.

On this day he has, with the inaugural party, sailed in the Tobaguilla around the bay, into La Boca of the Rio Grande, where young Mademoiselle Fernanda de Lesseps was to have inaugurated the work of the canal, by digging with childish shovel the first little sod of all the earth that separated the Atlantic and Pacific. But, as it had grown late, in this land where darkness comes on with sudden rush, they agreed to consider the entrance of the steamer into the river as the opening of the work of the canal—and omitted the shovelful of Isthmus swamp; thus beginning the gigantic enterprise by a makeshift—one of the many that they made—till makeshifts were of use no more.

Returned from this excursion, tonight Fernando Montez is at one of the minor banquets that take place before the ball.

It is in one of the smaller rooms of the Grand Hotel. Several of the attachés of De Lesseps are at the table—a Paralta, a Diaz, and one or two others of the leading families of the Isthmus. It is a gentlemen’s dinner party; and though the great Frenchman is not there in person, all are enthusiastic about the canal which is to give every one a chance to grab a fortune.

Among them sits one Anglo-Saxon—a man of about twenty-eight years, who has a pleasant though weak face, surmounted by light hair, and adorned by a moustache and goatee, the cut of which are French. His costume is rather that of Paris than America, as far as a dress suit permits.

“The stock must be subscribed for at once!” cries Montez. “The fever must not be let grow cold in France.”

“Oh, trust De Lesseps for that!” answers one of his satellites, Monsieur Dirks, Dutch engineer, who has dug canals in level Holland.

“Let me be the first to subscribe!” says the Franco American. Here he whispers to one of the French attachés: “Please hand my name for the first one thousand shares to your chief, the Comte de Lesseps!”

“The first one thousand shares subscribed for by an American!” There is a buzz of excitement around the table. The champagne glasses clink.

“A health,” cries Montez, “to the great Republic and the American, Mr. Frank Leroy Larchmont!”

“I beg your pardon!” says the gentleman he toasts.

“Don’t put me down as an American. Register me as a Franco American—Franc̗ois Leroy Larchmont.”

“But you live in the United States?” says Jose Peralta who sits next to him.

“I did once. Now I consider myself a Parisian!” Which in truth he does.

“This gentleman who takes one thousand shares so eagerly—I know his name—but what is he?” whispers Montez to the Frenchman sitting next to him.

“Oh, he is very rich, I believe! That is all I know about him. He lives in Paris, has the good taste to like France, and very seldom visits his native land.”

Then the banquet goes on, but during its conversation, buzz and excitement, Montez’ eye, sleepless and relentless, never leaves the face of the Franco-American who has taken the one thousand shares.

Fernando Gomez Montez has determined to make himself one of the rich men of the world by this canal; as many more did about that time, some of whom succeeded. He is shrewd enough to foresee, this cannot be by the dividends it will pay to its investors, but in the immense amount of money that must be handled, and rolled about, and circulated from hand to hand and check book to check book during its construction.

His subtle mind can easily grasp the idea that in this great “grab game” some of it must come into his clutches. This gentleman, who rushes so eagerly into a scheme just set on foot, whose face has a peculiar weakness not often seen in men of the United States, may possibly be a very good chicken to pick in the great pluckings and pickings that will take place during all the financial evolutions of this great enterprise.

As soon as cigars pass about, and the formality of the dinner becomes somewhat relaxed, he contrives to get his chair beside that of Mr. Larchmont, and their conversation, from being that of first introduction, becomes freighted with some of the confidences of friends.

Mr. Larchmont, to Fernando’s deft questioning, informs him that though educated partly in America, and his family entirely American, he has lived from his seventeenth year mainly in Europe and Paris. “Paris,” he says, “I regard as my home. I have a young brother in the United States, who is only twenty now. I am afraid he is too American to ever become a Parisian like myself.” But here their conversation is disturbed.

A dapper young man, with the quick address of one to whom time is money, and the manner of “no time like the present,” enters the room, and says: “Pardon my stopping the champagne, Monsieur Dirks. I believe you are one of the engineers in control of the preliminary surveys of the canal?”

“I have that honor,” says the Hollander.

“Then, between drinks, permit me to ask you four questions. First, when do you expect to open the Panama Canal that has been inaugurated today?”

“Certainly,” replies the Dutch engineer, astonished at the abruptness of the address. “In five years at the latest. In 1885.”

“You are sure?”

“So confident that I would write it in letters twenty-four feet high!”

“Then can you tell me how you are going to provide for the tremendous floods in the Chagres River that wash down, each rainy season, dirt enough to fill up the whole canal?”

“That will be by means of a large dam and reservoir sufficient to hold the average rainfall of a week.”

“But when the rainfall is more than the average, what will you do with it?”

To this, the Hollander replies evasively: “Are you an engineer?”

“No!”

“Then why do you ask engineering questions?” he replies sternly.

“It is because I am not an engineer that I ask engineering questions. If I were an engineer, I could determine things for myself.”

“Ah, then I will tell you. The floods in the Chagres will be provided for—later.”

“Then, the floods being provided for, what will you do with the higher rise of tide in the Pacific than the Atlantic?”

“That will be provided for later also!” returns the Dutch engineer savagely. And others of the Latin races at the banquet look with angry eyes upon this young man who stays their festival. Who is this creature that dares interrupt their night of triumph by impertinent queries that tend to throw doubt upon their grand scheme?

“Then, all this being settled, will you tell me how you are going to build the canal if you don’t get the permission of the Panama Railroad, which by its concession from the Colombian government must give its consent before you can dig a barrelful of dirt out of your gigantic ditch?”

At this question, the guests rise with foreign indignation and South American swagger.

“That,” shouts Dirks, wildly, “will be provided for by Monsieur le Comte de Lesseps. When he visits the United States, he will obtain from the Panama Railroad the requisite consent.”

“Not unless he pays Trainor W. Park pretty well, if I know him,” replies the young man. “I have just got time to telegraph your answer.”

“Ah, you are an emissary!” cries a French attaché. “An emissary of the United States, that is now making such a shriek about the accursed Monroe doctrine!”

“I am no emissary!” the intruder gasps, dismayed, for two or three Latins have gathered about him threateningly, and one, a young Chiliano, is handling a carving knife as if it were a cuchillo. “I am merely a reporter for the New York―” He can say no more, for at this instant he is rushed from the room and hurled down stairs, which perchance saves his life, as the Chiliano does not reach him in time.

Looking on this, the Franco-American says disgustedly: “You see the crude manners of my country men. No wonder I fly from them! You will appreciate my embarrassment, Señor Montez, at this uncouth scene. I have been lately to New York, to try to induce my brother Henri to live with me in Paris, but he declines. Over his actions I have no control; but my ward, Mademoiselle Jessie Severn, as her guardian and trustee, I am taking with me to Paris. I made a short tour in America, and while in San Francisco, thought I would come to Panama, to see the opening of this great French enterprise, and from here take passage in the Transatlantique line from Colon to France.”

“The young lady, your ward, is with you;” remarks Montez indifferently.

“Oh, yes; she and her governess and nurse.”

“Ah, she is not a young lady?”

“Not yet. She is but ten. I am taking her to Europe, to educate her in the manner of my adopted country. I do not approve of the way in which girls are brought up in the United States. Heiresses in America become so bold and self-reliant. They even assert their independence to the extent of selecting their own husbands.”

“Ah, an heiress!” thinks Fernando, his eyes opening a little wider at the news, for here may be two fortunes to play with; not only that of this rich gentleman, but also that of his ward.

So he proceeds to weave the first meshes in the web of the spider around this Franco-American fly. His conversation grows jovial, and full of anecdote, repartee, and wit. Incidentally, by adroit questions that seem more suggestions than queries, he learns what he wishes to know of the other’s character and life; and, though it is conveyed to him with reluctance, discovers that Mr. Larchmont’s father had been at one time a tailor in New York, and turning the money he had received for dress suits, overcoats, and trousers into city real estate, had become one of the magnates of Manhattan, though his elder son was almost ashamed to own him, notwithstanding the very handsome estates he had left behind him to his two sons and co-heirs.

“Ah!” remarks Montez, to this revelation, “no one can avoid bourgeois ancestors in the United States; it is land of trade and money.” And he sneers at the tradesmen in his mind, as the robber always does at the merchant.

Then noting that the gentleman sitting opposite him seems somewhat ashamed of his commercial American ancestors, and drags into his conversation every one he knows of title or rank in the Old World, Montez’ occult mind divines that to thoroughly and easily trap this man who is ashamed of his commercial country and tailor birth, he his captor must be of the nobility.

Then he mentions parenthetically: “Though you of North America have no aristocracy, South America still clings to hers. The Hidalgos of Spain never forget that they are grandees. As such I remember my ancestors!” and a drop of the blood of one of the Spanish Conquistadores coming into his eyes, this gentleman looks very haughty and exclusive to his Franco-American acquaintance.

Shortly after, they stroll from the apartment in which the little banquet has taken place, towards the ballroom. As they pass through the corridor of the hotel, which is brilliantly lighted, a charming figure trips toward them. It is that of a beautiful little girl, who is dressed like a sylph in gauze and fancy flowers and whitest muslin.

She is attended by a French bonne, trying in vain to restrain her charge, who comes eagerly towards the gentlemen, exclaiming, “Mr. Larchmont—Frank—Guardy! Look what the count has given me.”

She exhibits one of the beautiful decorations the charming gentleman had had made for distribution among the ladies of Panama—a mass of colored enamel and solid gold, and bearing the Colombian coat of arms, and an inscription in Spanish announcing the inauguration of Del Canal Interoceanic by Count Ferdinand de Lesseps.

These exquisite badges had been scattered broadcast among the youth and beauty of Panama, little drops in the ocean of expense that was to come, but bearing promise of the lavish manner in which gold would be thrown broadcast over promoters, jobbers, contractors and employees—in short, on everyone engaged in this gigantic enterprise—SAVE THE SHAREHOLDERS.

Delighted with her present, the child stands poised on tiptoe, one hand held upwards towards her guardian, one little foot advanced. With bare white arms and graceful pose, the short skirts of childhood displaying fairy limbs, she looks to Montez like a ballerina idealized. For she has the blonde hair and blue eyes that dark nations love so well; and her figure, draped in the light dress of that warm climate, gives promise of faultless development in an early future.

“This is my little ward,” says Larchmont, examining the pretty bauble she holds up to him. “Miss Jessie Severn, permit me to present Señor Montez.”

“Baron Montez.”

“Ah!” is the little surprised exclamation from the American.

“Yes, we are old Castilians, we Montez, and like all Spanish Hidalgos, punctilio itself about our name and our titles. You will excuse my mentioning it to you,” says Fernando, with a pleased smile at his own inspiration. “Baron Fernando Montez.”

But here the little girl breaks in upon them, and says: “How curious, Mademoiselle Fernanda de Lesseps was to open the canal today, and you are called Fernando! Fernando Montez—that’s a pretty name! I call little Fernanda, Tototé; must I call you Tototo?” Then she looks at the little figure of the ennobled gentleman, and gazes curiously at his jetty hair that is just beginning to show a little silver on the temples, and notes his mobile mouth play under his waxed moustachios, and his very white shirt, which has a decoration upon it—some old Spanish order he had picked up in some Peruvian cathedral. Next the blue eyes of happy childhood glance up fearlessly at the bright orbs of the newmade noble that have opal flashes in the gaslight; and, somehow, though this child had never felt fear before, her eyes droop before those of the all-nation gentleman, and she is happy when her guardian says: “Jessie, it is time for little girls to be in bed.” So mademoiselle trips hurriedly off to her governess, followed by the sleepless eyes of Montez.

“You have made quite an impression on my little ward,” whispers the guardian.

“Ah, you ravish me with delight!” cries Fernando.

And so he has; for the little girl is murmuring to her elf: “Bluebeard, Bluebeard—naughty Bluebeard!” and trembles as she runs along.

The Hidalgo is pleased to see that his title has made an impression upon the Franco-American. He remarks, for the beauty of the child still lingers in his senses, “Miss Jessie will soon be ready to bless some happy man with her hand—this little beauty!”

“Pooh! She is only ten. That will be years from now!” says Larchmont easily. Then he goes on: “But I see in this tropic land the ladies develop early,” and casts his eyes over the bronze shouldered Inezes and Doloreses, as they are trooping into the ballroom.

“Yes, we would marry her at fourteen here!” laughs Montez. “But even in France, in a few years she will be ready for her trousseau—about the time the canal will be open. You might celebrate both fêtes together, when you have selected the husband.”

Then the buzz of excitement coming in through windows that are always open, save during thunder storms, in this torrid city, attracts the gentlemen. They step out to catch the night breeze that comes refreshingly to their cheeks, and look down upon the great Plaza of Panama, with its green plants and paved walks, in which the crowd are promenading, the great cathedral standing at their left. For this is the old Grand Hotel—the one that afterwards became the offices of the Panama Canal—which is decked to-night for gayety.

Looking at the cathedral, a grim smile comes over the face of Montez, and he sees in his vivid imagination a bridal procession going up its great aisles to music of the organ and chant of dusky altar-boys, and picturing the bride with blue eyes and blonde tresses, thinks to himself: “Why not I for the bridegroom? I am not old! She is rich. The man beside me is weak. Perhaps with another fortune may come to me another beauty.”

The noise of the moving crowds below breaks in upon his reverie, and Larchmont suggests: “Suppose we see the ball.”

They go in to the dance where Spanish beauties, in the ball-dresses of Europe, jostle French and Colombian uniforms and black dress coats; and the grand old man dances quadrilles with lovely Inezes, Marias, and Manuelas, to have his agility telegraphed all over the world, so that doubting French peasants may invest their stocking hoards in his newest and grandest enterprise, still thinking him the man of Suez, when Ferdinand de Lesseps is in reality beginning a dotage, awful in its consequences, to his friends, his government and his country—because it is unsuspected.

So the ball goes on to its climax, amid the strains of the latest waltzes, and the clinking of champagne glasses in the supper room, and the laughing eyes of Spanish beauties, and the babbling tongues of sycophants and hangers-on.

And on this night of triumph, when De Lesseps inaugurates the work on the Panama Canal, this night Fernando Montez gives to himself nobility and a title that will give him weight in Europe and influence over weaklings like the one he has set his eyes upon this evening. So the black drops in his veins become blue, azure, and noble; even the little Congo negro he has in him changes to old Castilian, as he exclaims: “Fernando Gomez Montez, I ennoble thee! Mule-boy of Cruces, I introduce you to Baron Montez!”

Full of his project, this very night he obtains a printer, who, under great promise of secrecy, for which he is heavily paid, furnishes early the next morning the following striking carte de visite.

This looks so beautiful to him that he cannot refrain from trying its effect early next morning.

Old Domingo, who is older by twenty-four years since the night he assisted to make Montez rich, lives with him, not as servant, but as kind of halfway guest, for the old man is well-to-do. The old pirate knows the buccaneer maxim: “Every man his share!” And he had had pirate enough in him to compel the moiety of the American’s gold due him from Montez.

On this he has lived and prospered, and though well over seventy, is still as hale and hearty and old a sinner as can be found in South America—which furnishes as fine a sample of ruffians as Hades itself.

“How now, Señor? You seem happy!” is Domingo’s greeting, as his mentor saunters on to his portico, having finished his alligator pear, sucked his orange, and drank his cup of coffee. “How now, Señor Montez?”

“Baron Montez!” corrects the gentleman addressed, severely.

“Caramba!”

“After this, Baron Montez! I have been ennobled,” remarks Fernando, shoving his ornamental pasteboard beneath Domingo’s rolling orbs.

“Ho oh! By the great fat Frenchman who is here?”

“Yes, the great Frenchman, who will make us all rich.”

“Sant Jago! Another massacre! There are lots of them here now! Beauties, too! Would I were younger!” mutters the ex-pirate, his eyes glowing with pirate gleam.

“No, not this time. They have more to give us if we let them live!” returns Montez in grim significance.

But the remembrance brought to his mind of that night in 1856, does not seem to please him. He looks curiously at Domingo, then gives a little sigh of relief; the appearance of his co-laborer indicates he will be forever close-mouthed. Time has made the rest safe. They are dead; even the beautiful Indian girl, Anita of Toboga, had become a hag at twenty-five, and died at thirty. Beauty that the sun nourishes most fondly, it soon scorches to death in these tropic climes.

So, with a contented smile, Fernando strolls off, to put his new nobility to use.

He sends up his card, with its coronet, to the Franco-American, and very shortly following it to that gentleman’s parlor in the Grand Hotel, is greeted by a “Good morning, Baron!” and an effusive grasp of the hand.

For one second he starts, thinking some one else is addressed—it is not easy to get accustomed to nobility overnight—then, with a smile, the “new creation” replies with affable hauteur.

Soon after, all others address him as Baron; none seeming to doubt his title, for these curious reasons: The French, knowing but little about him, think he is a true Spanish Hidalgo. His Colombian confrères, some of whom have known him even when he was an altar boy in the Cruces chapel, think Fernando has received his patent of nobility in some peculiar manner from le grand Francais De Lesseps. Besides this, they are very much occupied about a revolution that they have been intending to put in progress, but have postponed, fearing their political shooting and slaying might delay the opening of this canal. They will, however, go at this quite merrily, as soon as Monsieur de Lesseps leaves Panama. So it comes to pass that the ex-muleboy of the Gargona trail, el muchacho diablo, becomes accepted by men as Ferando Gomez, Baron Montez, and prepares to air his title in the salons of Europe and the Parisian Bourse.

Notes and References:

- Le Grand Franc̗ais: a title bestowed on Ferdinand de Lesseps by Léon Gambetta, a French statesman, a revolutionary Republican known for his brilliant oratory. De Lesseps withdrew from the election in the District of Marseille in order that Gambetta might win it, and Paris District.

- Comte de: count, earl.

- cholera Asiaticus: Asiatic cholera pandemic (1826-1837), was “a cholera pandemic that reached from India across western Asia to Europe, Great Britain, and the Americas, as well as east to China and Japan.”

- el vomito negro: alternative name for acute viral yellow fever.

- la boca: French—the mouth.

- confrères: a fellow member of a profession, fraternity, colleague.

- Chiliano: Chilian.

- cuchillo: knife.

- carte de visite: visiting card, i.e. a calling card. Notably a type of small photograph which was patented in Paris by photographer André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri in 1854.

- bourgeois: member of middle class.

- sylph: “a slender, graceful woman or girl. (In folklore) one of a race of supernatural beings supposed to inhabit the air” (dictionary.com).

- bonne: French—a child’s nurse.

- punctilio: a fine point, particular, or detail, as of conduct, ceremony, or procedure.

- moiety: a half, or an indefinite portion, part, or share.

- hauteur: haughty manner or spirit; arrogance.

- Bourse: stockmarket—the Paris Stock Exchange

Bernstein, S. “The Impact of the Paris Commune in the United States,” The Massachusetts Review

Vol. 12, No. 3 (Summer, 1971), pp. 435-446.

“Monroe Doctrine; December 2, 1823“. Yale Avalon Project: Documents in law, history and diplomacy.

Parker, M. Hell’s Gorge: The Battle to Build the Panama Canal (London: Arrow Books, 2007).

This edition © 2021 Furin Chime, Brian Armour