Vadalia Cardinalis is an insect now known as Rodolia Cardinalis due to an etymological reclassification, though its common name remains the same. It is a name that most know from a childhood rhyme, but Gunter keeps this his little secret, for revealing it would seriously damage the analogy he uses later in the chapter for the Baron and his intentions. Having no access to handy etymological works, Gunter can be reasonably confident that his readers will remain ignorant. The narrator is practically rabid in describing this insect which freed of normal dimensions verges on a creature from science fiction. While quite appropriate to compare Montez to an insect, he does not have the charm of this Australian import. See closing notes for the terrible truth.

Baron Montez is back in Panama, hot on the heels of chanteuse Mademoiselle Bébé de Champs Élysées. Bébé‘s disaffection with the now truly heart-struck Harry Larchmont, involving a promised string of pearls, leads her to disclose Harry’s presence in Panama to the Baron. The string of pearls serves to revive the reader’s memory of pearls procured by Fernando Montez for the beautiful Alice Ripley all those decades ago. The Baron’s reflections on his own loose lips compel him to consider those of his cher ami next to him in sinister overtones.

Montez meets with Herr Wernig, and at the close of their discussions the topic of ‘the Lottery’ is raised. Some of Gunter’s readers of the time may have been aware of the significance of this Lottery, but for the modern reader some background is definitely required. In the proposed Lottery, two million bonds would be offered bearing 4 per cent interest at a cost of 360 francs each. These bonds would be redeemable in ninety-nine years for 400 francs. Draws would occur every two months with top prizes in the vicinity of 700,000 francs. The lottery bill would allow the Company to borrow a 720 million francs, 600 for completion of work on the canal and the remainder to be invested in French government securities to guarantee payment on the bonds and to provide cash prizes (Parker, p.183).

The financial future of the Canal is tenuous—it has always been so. Lotteries are one method De Lesseps has used successfully in the past to gain funds; however, to take place the project had to be considered of national importance and also required an Act of Parliament.

The new government was reticent to approve a Lottery and delayed a decision. Well-known engineer Armand Rousseau was commissioned by the Minister of Works to go to Panama and provide a report for the government. Rousseau submitted his report in April, 1886. Although critical of the management of contractors, and the challenges of a canal without locks, the report was largely favorable, based upon the extent of the work completed and the depth of the French commitment, in terms of government backing and the French people’s investment thus far (Parker, pp.163,169). The project had reached a point of no return where the risks of continuing outweighed the prospect of ceasing the undertaking. Despite this, over two and a half years since Rousseau’s report, the Cabinet declined to support the bill to the Chamber of Deputies. Much lobbying, petitions and bribery failed to sway the Cabinet. De Lesseps could not wait any longer and went with another bond issue, but this did not perform well. He was forced to borrow thirty million francs from Crédit Lyonnais and Société Générale so that the company could survive.

Finally, on the 28th April 1888 due to the support of a hero of the Franco-Prussian war, Charles François Sans-Leroy, the Commission approved the bill by six to five. The company although receiving permission for the lottery, did not garner government backing of the bonds, and so were required to state this in their prospectus (Parker, pp.181-2). The success of the lottery is another matter.

CHAPTER 17

VADALIA CARDINALIS

Then Mademoiselle de Champs Élysées and Harry Larchmont pass on, the crowd gathering about them with hum and chatter and merry voices, and screening them from her view; and the girl, who has thoroughbred pluck, and whose eyes have looked the gentleman very straight in the face, suddenly feels faint, and thinks the sun has gone out of the heavens, for love, trust, and faith in humanity have gone out of her heart also.

She notes, in an abstracted way, that Martinez is making some little joke upon the appearance of the French woman: for though he has told his daughters not to look, the old notary’s eyes have devoured the beautiful yet too highly colored picture La Champs Élysées has made.

After a little the young Martinez ladies suggest going home, and Louise is very glad, and departs with them to her lodgings, carrying her head quite high and haughtily, though she has a heart of lead and iron within her wildly panting bosom.

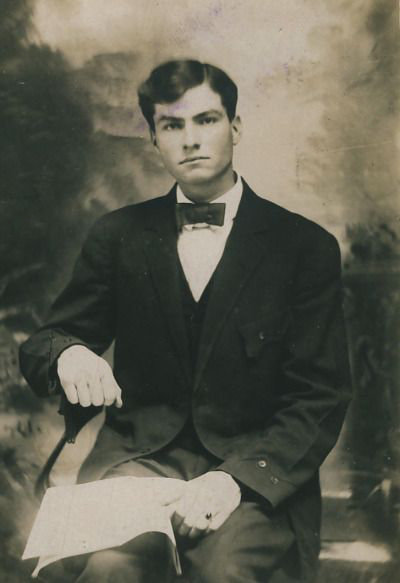

But she has left a picture in the eyes of Harry Larchmont that he will never forget! That of a girl with a light straw hat, the ribbons floating in the breeze above her lovely head—a graceful figure posed like a statue of surprise, one little foot advanced from under white floating draperies, the other turned almost as if to fly. A sash of blue shining silk or satin, knotted by a graceful bow about a fairy waist; above it, a bosom that pants wildly for one moment, and then seems to stop its beating, as her hand is wildly pressed upon its agony. But the face! The noble forehead; the true, honest, hazel eyes, which flash a shock of unutterable surprise and scorn for debased mankind, and nostrils panting but defiant; pink cheeks that grow pale even as he looks upon them; rosy lips that become slowly pallid, the lower trembling, the upper curled in exquisite disdain; the mouth half open, as if about to speak—then closed to him forever; and over all this the infinite sadness of a woman’s heart for destroyed belief in what she had considered a noble manhood.

And his heart stops beating, too, for even as he looks at her comes a sudden rapture, then a chill of horror—rapture, for at this moment he guesses that she loves him; horror, because he knows she will love him no more.

Turning from this picture of pure womanhood, he sees beside him the woman for whom he has lost all hope of gaining what he now knows has been his hope in life. For the shock of her disdain has told him something a false pride had made him fight against believing; that he, Harry Larchmont of the world of fashion, loves Louise Minturn of the world of work with all his heart and all his soul.

Though Bébé de Champs Élysées utters her latest piquant drolleries imported from Paris, and tries her best to amuse and allure this handsome young American who strolls by her side, and whom she supposes rich, for he has squandered money on her, she finds him but poor company. He contrives to reply to her, but her flaunting affectations seem more meretricious to him than ever.

After a little time he excuses himself to Mademoiselle Bébé, and leaves this fascinating siren surrounded by a crowd of gentlemen admirers, for her notoriety, as well as beauty, have given her quite a following of highlife worshippers in this town of Panama.

As he goes away the band is playing one of the Spanish love songs Louise had sung to him in the moonlight on the Colon’s deck, and he mutters to himself, crushing his hands together, “My dear little sweetheart of the voyage! Fool that I was! I have lost her for a fantasy!” Which is true, for no love of Bébé de Champs Élysées had ever entered Harry Larchmont’s heart.

He had gone into this affair rather recklessly, simply seeking information that he thought she could give, and for which he was willing to pay. As to its moral sense, he had given it very little consideration. It had simply occurred to him that by it he might destroy his adversary. In New York he would doubtless have hesitated before embarking in a matter that might bring scandal upon his name; but here, in this far-off little place, which has the vices of Paris, without even its slight restraints, he had dismissed this aspect of the affair from his mind, with the trite remark: “When you are in Rome, do as the Romans do!”

So Baron Montez not being on hand, Harry Larchmont has obtained a passing introduction to this siren of the Boulevards upon her arrival. He has made his approaches to her quite cautiously, and with all the secrecy possible, not wishing to form part of the petite gossip of Panama. Having spent quietly considerable money and considerable time in trying to insinuate himself into her good graces, he has succeeded in gaining perhaps more of Mademoiselle Bébé’s regard than he himself would wish.

Her confidences, for he has been compelled to approach the matter very deftly, have been so far only confidences as to what kinds of jewelry she likes most. In fact, a great deal of her conversation has been in regard to the wondrous string of pearls that a merchant has brought from the Isle del Rey, that are, as she expresses it, “dirt cheap!” For this young lady has an eye to business, and knows that the traders of Panama have not as fine diamonds as those of Paris, yet in pearls they sometimes equal, sometimes excel them.

Her promptings and petitionings have been so persistent, that Harry knows that the gift will probably win from her the information that he wishes, and that when the pearls of Panama adorn Mademoiselle Bébé’s fair neck, she will perchance in a gush of rapture open her pretty lips, and tell him what she knows, if he pumps her deftly.

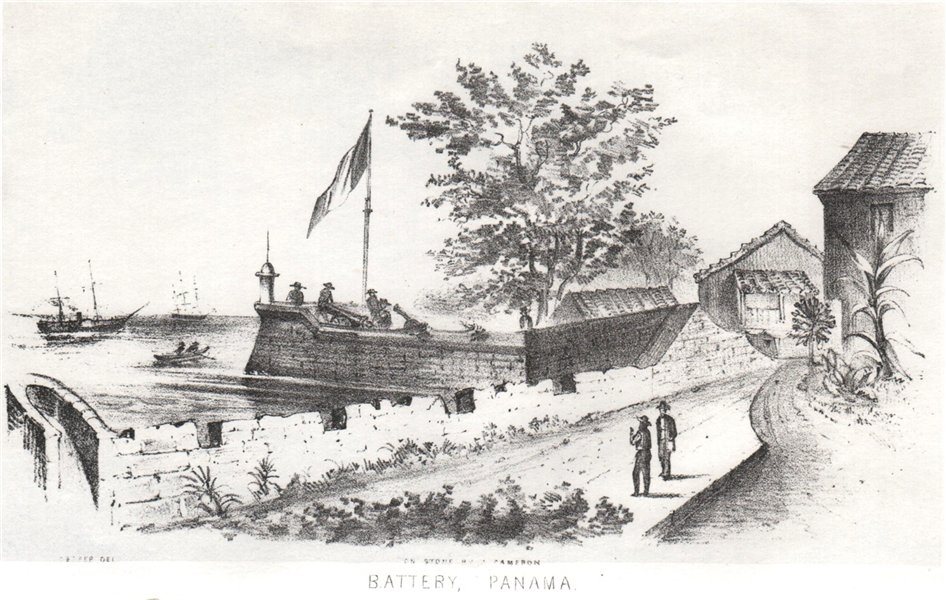

So this very Sunday he has this string of pearls in his pocket, having purchased them the evening before, and was about to present them to her. But even while he is arranging a little coup de théâtre that may unloose the siren’s tongue, she has insisted upon his visiting the Battery in her company; for this lady likes to make public display of her conquests, and Larchmont is a very handsome one. Some sense of shame being on him, even in this free-and-easy, out-of-the-way place, Harry has declined her invitation.

But Bébé’s temperament will not brook denial even in little things; she has turned upon him and said: “Mon ami, are you ashamed to be seen by the side of the woman to whom you express devotion? If I thought that, my handsome Puritan, I should hate you—you have never seen Bébé’s hate.”

Under these suggestions he has yielded, and been led very much like Bichon, her poodle, in triumph to the Battery of Panama, there to meet what fate had prepared for him.

But now shame changes this man’s ideas. He mutters to himself: “The cost is too great! I will not win success at the degradation of my manhood! though, Heaven help me! I fear I have already paid the bitter price!”

From this time on he visits Mademoiselle de Champs Élysées no more.

But his desertion produces a curious complication, and brings the siren’s undying hate.

Among the gentlemen who pay their devotions on the Battery this afternoon to Mademoiselle de Champs Élysées, immediately after Harry’s departure, is young Don Diego Alvarez, who has lingered in Panama, waiting for the steamer to carry him to Costa Rica. This fiery young cavalier still hates, with all his Spanish heart, Mr. Harry Sturgis Larchmont. His regard for him has not been increased by his apparent success with the coming celebrity at the theatre. He has learned that Larchmont is a clerk in the Pacific Mail, and sneers at him as such, and laughs to himself: “What will be the effect of my news on the mercenary diva?”

So he strolls up to her, and enters into conversation, remarking: “I am delighted, Mademoiselle Bébé, to see at least one woman who admires a handsome man, even if he has no other attractions.”

“You don’t mean me?” laughs the lady in gay unbelief.

“Certainly, you!”

“And who is the gentleman? Of course I’ve never seen him yet.”

“Why, that American, Senor Larchmont.”

“Oh, Henri,” says the young lady in playful, easy familiarity. “Henri has plenty of other attractions. Besides good looks, he has money!”

“Money?” sneers the Costa Rican.

“Yes, money!”

“But not much money.”

“He has enough to promise me the great string of pearls that have just come from the islands!”

“What? This clerk in the Pacific Mail Company, at a beggarly salary, buy the great string of pearls?” scoffs the Costa Rican.

“This clerk in the Pacific Mail Steamship Company! Whom do you mean?” gasps the fair Bébé, growing pale.

“The Señor Harry Larchmont.”

“Impossible!”

“You can convince yourself of the truth of what I have said, easily enough tomorrow, or this evening, if you are in a hurry,” laughs Don Diego.

“And he promised me that string of pearls, the misérable! He played with my heart!” gasps the lady, placing her hand where that organ should be, but is not. “A clerk in the Pacific Mail—an accountant—a beggarly scribbler! But I will investigate! Woe to him if it is true!”

Being a woman of her word, not only in affairs of the heart but in matters of business, this lady makes inquiry and finds that what she feared is true; and would have vented her rage upon Mr. Larchmont had he appeared before her. But Harry keeping aloof, she changes her tune in reference to this gentleman, for she is an inconstant creature, longing most for what she has not. She mutters: “The poor fellow! I frightened him away by my extravagance. I would have forgiven his being a clerk, he is so handsome!”

But the pearls being still in her head, she thinks she would like to take a look at them; that, perhaps, as Baron Montez is coming, he may be induced to purchase them; and she goes to the shop of Marcus Asch the jeweller near the Cabildo, and asks for the baubles that she will gloat over and admire. But they inform her that the pearls are gone.

“Gone? Absurd! They were here last Saturday!”

“Yes, but Señor Larchmont bought them.”

And perchance if Harry could have seen her then, he would have bought from her with his pearls any revelations of chance words Montez had let fall in the confidences of the champagne glass or petite supper; for Bébé, like Judas, will betray her master for the ten pieces of silver as often as they are laid at her feet.

But Larchmont does not receive her note. He has gone away, along the line of the Canal, towards Aspinwall.

“Mon Dieu! Impossible!” she screams; and then going away, mutters: “Malediction! if he has given them to another!” but sends the gentleman who has bought the pearls a most affectionate note.

So she grows very angry and thinks to herself: “What other one has received what were bought for me? I will punish this traitor!”

That afternoon Baron Montez arrives in Panama.

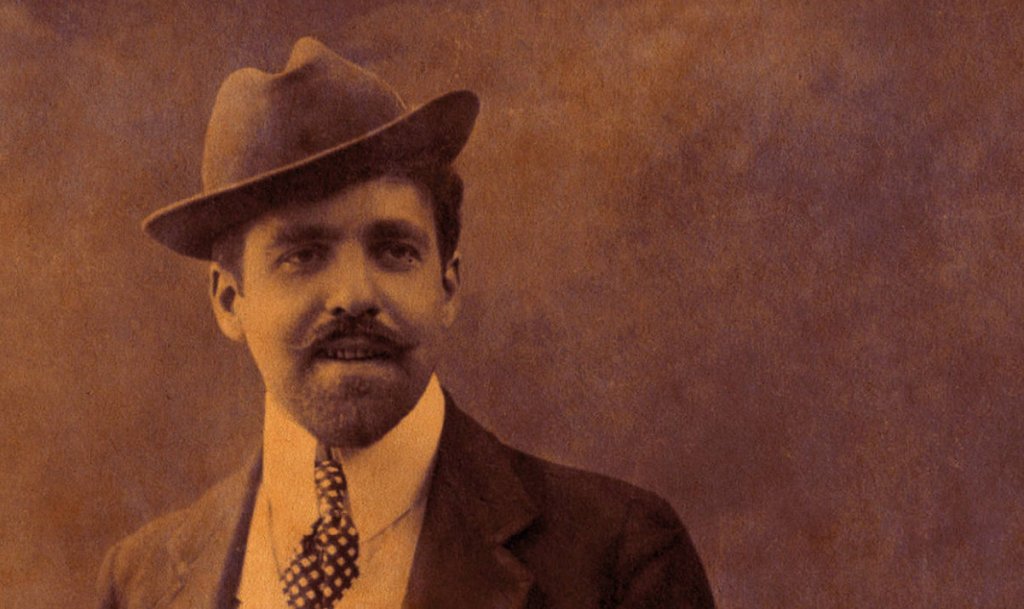

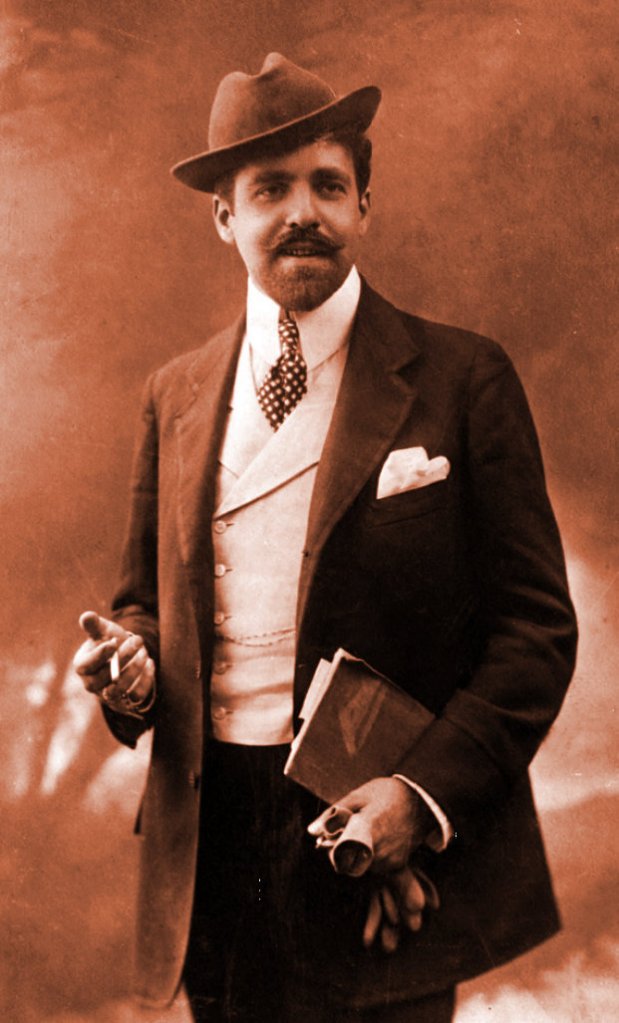

This gentleman is apparently quite happy and contented as he drives up from the railroad station in company with his partner and Herr Wernig, and enters his office, hardly noting that there is a bright-eyed girl who looks up from her work in the room behind the private office with curious interest at him. His years have been successful ones, and though there are two gray locks upon his temples, his eyes are as bright as of yore, and his intellect as vivacious, though tempered by contact with other brilliant minds.

He gets through his business rather quickly in his office, saying to Aguilla, who would be effusive, “Tomorrow, mon ami. Tonight my comrade Herr Wernig and I will talk over old times.”

So the two go away together to the Grand Hotel, where Montez has the finest apartments and is received by Schuber the proprietor with much deference and many bows; for though the Baron has been careful never to have his name upon the directory of the Panama Canal, still he is known to be in very close touch to its management and control.

After dinner the two stroll up to the theatre where Mademoiselle Bébé is waiting for her cher ami, with many evidences of petulant affection, one of them being a revelation of “l’affair Larchmont.”

First greetings being over, this little poseuse affects a jealousy she does not feel. She pouts and mutters, “You came not to Panama, Fernando mio, as soon as you promised.” Then her eyes flash from absinthe or some other French passion, and she cries, “Ah! It is that little minx of the Boulevard Malesherbes! But I’ll teach her when I go back!”

“I pray you not to mention that young lady’s name!” says the Baron, looking at her rather curiously.

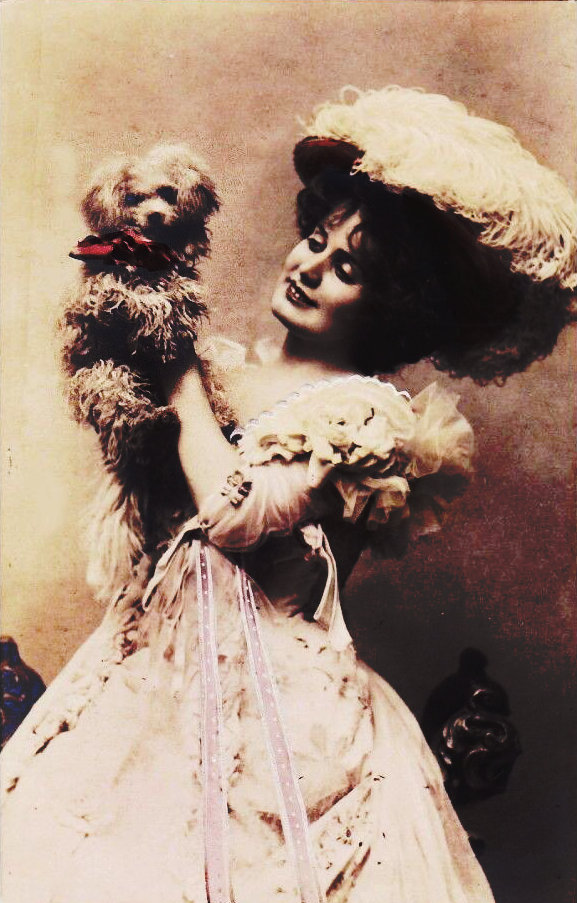

“Tut! Tut! What do I care for those savage eyes of yours, Monsieur le Baron?” laughs the lady. “I can have other admirers!” As she easily can; for even now she makes a most alluring appearance, her costume de theatre being such as to display beauties of the figure as well as the face; of which Bébé de Champs Élysées has many, though most of them are of the “Robert le Diable” enchantress order.

But Montez not answering her, she babbles on, “You don’t believe me! You have not yet heard of the handsome young American whose eyes are as bright and big as your friend Herr Wernig’s, though mon Henri’s are straight, not crooked.”

“Mon Henri’s,” mutters the Baron, giving her an under glance.

“Yes, mon Henri, who is wild with love for me. So wild, he offered me a great string of pearls worth a fortune. But for your sake, ingrate, I repulsed him!”

“Ha, ah! ma chère! That means, you want a string of pearls!” laughs Fernando, who knows this lady’s tricks and manners very well.

“I do!” answers Bébé, “but not from him! Had I wished them from him, they would have been mine! I think, from certain hints of his, he wanted some revelation from me. A revealing of some of your careless remarks over supper table and champagne glass, of your connection in business with his brother, Monsieur Francois Larchmont.”

“Larchmont!” cries Montez. “Oh, it is that younger brother who has come here to the Isthmus?”

“Certainement!”

This suggestion makes Fernando very serious. Though Montez is a great man, like most great men he has a weakness. A drop of blood from a Gascon adventurer in his polyhaema veins, makes his tongue over a champagne glass sometimes throw away careless hints of things it were wiser not to speak of. This is especially his nature when he has been triumphant; and he has been triumphant so many times over the careless trust of Francois Leroy Larchmont, that he fears he may have dropped some suggestion that the lady beside him might under duress, or lured by gold, betray. And did she but know it, poor laughing méchante Bébé’s tongue has been doing some industrious work on her sepulchre just now.

Baron Montez looks at her curiously, then as she stands babbling to him, waiting for her cue at the side scene, puts off this short-skirted, white-shouldered siren with a few careless words; and shortly after, leading his Fidus Achates, Herr Wernig, from the theatre, plies him with some very pertinent questions about the young American, as they stroll towards the Plaza.

After getting his answers, Fernando gives a chuckle and ejaculates “Parbleu! This young bantam has come to fight me on my own dunghill!”

Then he listens in an abstracted way as Herr Wernig goes on in further explanation: “You wrote me about him. I watched him carefully. He is supposed to be a clerk in the Pacific Mail Steamship Company’s office, but he does as he pleases. He also had quite a flirtation on the Colon coming out, with that pretty stenographer in your office.”

“Oh, yes,” remarks Montez, “the girl I saw this afternoon. I remember I told our agents in New York to engage one. I thought an American would be less dangerous than a French one to our confidential communications. Personally, I always write my own letters of importance, but poor Aguilla is not good with his pen, and requires a correspondent.”

“Poor Aguilla? Rich Aguilla! He’s your partner,” laughs the German.

Here from out Montez’ white teeth issues a contemptuous “Bah!” and Herr Wernig, after a pause of thought, gives a little giggle.

“As to the young lady stenographer, I will ask her some questions in the morning. You say she was épris with this Larchmont?” murmers Fernando, puffing his cigarette very slowly.

“Oh, very much, but there has been some trouble. She has not spoken to him since they left the steamer. I saw her cut him very directly on the Battery last Sunday, when he was walking with Mademoiselle Be̕be̕, for whom I understand he bought the big pearls, but did not deliver them.”

Into this Montez suddenly cuts: “You leave tomorrow morning?”

“Yes, by a quick steamer to St. Thomas, and then to Paris.”

“Of course! to add your weight, Wernig, to the Lottery Bill that is to permit the Canal here to make one last big gasp before it”—here Fernando lowers his voice—“dies.”

“Certainly!”

“You need have no fear. The bill will go through the Corps Législatif. Then a spark of life, but after a little time there will be an end of the ditch. However, it is very important that this Lottery Bill pass, for you and for me. By it we will get the moneys due us from the Panama Canal Company, which are at present delinquent. After that no more contracts for me!”

“For me also!” laughs the German. “Don’t you think I have seen this as well as you?”

“Ah, you have come here to clean up—so you need not return?”

“Yes, I have done so pretty effectually.”

“I am here to clean up also, and very thoroughly. If the Lottery Bill did not go through, work would stop here at once, and there are some in this dirty little town who would call themselves my dupes, and perhaps wish my blood—the blood of poor, scapegoat Montez—the innocent blood! But in two months I shall be safely out of all this, so vive la loterie!”

“I wonder you did not remain in Paris till the bill passed!” says Wernig inquisitively.

“That was impossible!” returns Fernando. “Besides”— here he whispers to the German who bursts into a guffaw and cries, “What! The Franco-American!”

“Yes! He is doing the buying; he is at my suggestion making himself amenable to French law. But you leave tomorrow morning for Colon,” continues the Baron. “I must bid you adieu tonight. I am not an early riser.”

Then the two go into some more private confidences, but as Montez bids Wernig goodnight, he whispers these curious words: “In a month you will see me in Paris. In a week or two I shall be away from here, and leave nothing behind me—nothing!”

Then looking around, he waves his hand with foreign gesticulation, and laughs: “I will have eaten them all up—I have such a big appetite!”

And the German seizes his hand and chuckles: “And so have I, my brother!”

So after a farewell glass of wine at the Café Bethancourt, these two part, with many expressions of mutual esteem, and many foreign embraces, and even kisses, they so adore each other; though Wernig has made up his mind to eat Montez, and Montez has made up his mind to devour Wernig.

Far away Australia, among other wondrous birds, beasts, fishes, and reptiles, has given birth to a most marvellous insect—the Vadalia Cardinalis! Its appetite is phenomenal, its voracity beyond description. Though not destructive to vegetable life, were it large enough, it would eat the entire animal world.

There is also a lazy lower order of insect that lives dreamily upon the leaves of the orange trees of California, known by the name of the Cottony Scale. Its form of life is so low that it seems more a white incrustation on the beautiful plants than an insect who lives upon their leaves and life.

Into the orange orchard, dying from myriads of Cottony Scale, the planter lets loose a few Vadalia Cardinali. These prey upon and eat up the lazy white Cottony Scale with incredible rapidity, and the beautiful plants, bereft of what is drawing their life away, survive and nourish. But after the Vadalia Cardinali have eaten up all the Cottony Scale insects in the orange plantation, with incredible voracity they fall upon and devour each other, and the survivors again devour. Each hour they become fewer and fewer, until there are but two Vadalia Cardinali left. And these two battle and fight with each other till one is victorious and destroys and devours his opponent. And from that orchard that once was white with myriads of Cottony Scale glistening in the tropical sun, and here and there a red spot of Vadalia Cardinali, but one insect crawls away, seeking for further prey for his all devouring jaws—one Vadalia Cardinalis!

Such an insect is Baron Montez of Panama. He has already eaten up and destroyed outside stockholders and investors in Panama securities—the weaklings, the Cottony Scales—such as Francois Leroy Larchmont and Bastien Lefort. Having devoured the Cottony Scales, he is now about to eat his own breed—his partner Aguilla, his old chum Wernig, his early companion Domingo the ex-pirate, who has invested his savings under Montez’ advice, and half a hundred other cronies of his, who have assisted in his work of despoiling the lower order of animal life. He will be the only Vadalia Cardinalis, who will leave his own particular plantation on the orange farm called the Canal Interoceanic.

Perchance he would be wiser, perchance he would have less care, perchance he would be more successful, if he let a few others save himself have a little of the pickings of his schemes; for even Cottony Scale bugs writhe in anguish sometimes, and some of the men he is about to devour are Vadalia Cardinali, ferocious, implacable, and cunning. For instance, Domingo the ex-pirate, and Aguilla, who has swindled many in his time in his honest bourgeois way. But to eat all is Montez’ nature; he is a Vadalia Cardinalis.

Notes and References

- Vadalia Cardinalis /Rodolia cardinalis: common name ‘ladybird beetle’, ‘ladybug’. See influentialpoints.com and Rice Univ. Insect Biolog Blog, ‘Invasive, Sex-Crazed Cannibals‘.

- meretricious: alluring by a show of flashy or vulgar attractions; tawdry, based on pretense, deception, or insincerity. Pertaining to or characteristic of a prostitute. [Latin meretrīcius of, pertaining to prostitutes, derivative of meretrīx prostitute, from mere-, stem of merēre to earn] thefreedictionary.com

- méchante: Nasty, villain, wicked, vicious,evil.

- Fidus Achates: faithful friend or companion—Latin, literally: faithful Achates, the name of the faithful companion of Aeneas in Virgil’s Aeneid. Collins Dictionary

- Parbleu!: For God’s sake!, By Jove!

- épris: love

- Corps Legislatif: French Legislative body

Parker, M. Hell’s Gorge: The Battle to Build the Panama Canal (London: Arrow Books, 2007).

Snyder, W.E. et al. “Nutritional Benefits of Cannibalism for the Lady Beetle Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) When Prey Quality is Poor“. Environmental Entomology, Volume 29, Issue 6, 1 December 2000, Pages 1173–1179. Available Oxford Academic.

This edition © 2021 Furin Chime, Brian Armour