In my previous post, I referred to Jibun’s description of two women outside Maruzen bookstore as having “a round face, in a flowery kimono, heavily powdered,” assuming them “naturally” to be geisha. His casual observation raises an intriguing issue about the perception of physical beauty across cultures, which will afford us a diversion touching on some cultural ideas about female beauty.

The Round Faces of Jibun’s Nihonbashi geisha: changing ideals of female beauty

Laura Miller’s book Beauty Up: Exploring Contemporary Japanese Body Aesthetics (Berkeley: U of California P, 2006) is a useful place to start. She observes the female aesthetic ideal through history, beginning with Heian era literature (794–1185), primarily Lady Murasaki’s Tale of Genji and Makura no Soshi’s Pillow Book.

A court lady ideally had a pale, round, plump face with elongated eyes. The eyebrows were plucked and repainted somewhat above their original positions. Gleaming white teeth were thought to be horribly ghoul-like, so they were darkened. Positive assessment of chubbiness was also common, as in descriptors like “well-rounded and plump” (tsubutsubu to fuetaru) and “plump person” (fukuraku naru hito). Perhaps most importantly, a woman’s hair should be long, straight, and lustrous, reaching at least to the ground.

Miller 21. See also her present source, Ivan Morris’s World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan (NY: Knopf:1964: 202; and Gary Hickey, Beauty and Desire in Edo Period Japan (Thames & Hudson, 1998)

There are some who argue that at that time teeth were blackened with paint, in order to simulate tooth-decay: this showed that the woman was wealthy enough to afford sweets, in the same way that her plumpness would show that she could afford plenty of food. (See Hiroshi Wagatsuma [1967], “The Social Perception of Skin Color in Japan“. Daedalus. 96 [2]: 407–443.) In later times, a liquid made from iron filings dissolved in vinegar was used. This procedure of ohaguro was considered a dental sealant for preventing tooth decay.

Female beauty norms of the Edo period (1603–1867) are documented in an ukiyo-e genre called bijin-ga, or “portraits of beautiful women.” These are usually “courtesans with long, thin faces, fair skin, small lips, blackened teeth, thickset necks, and rounded shoulders” (Morris 21; and see Shinji and Newland; and Hickey).

See also:

- Hamanaka Shinji and Amie Reigle Newland, The Female Image: Twentieth Century Prints of Japanese Beauties (Leiden: Hotei Publishing: 2000)

- Gary Hickey, Beauty and Desire in Edo Period Japan (London: Thames & Hudson, 1998)

Actually, it is not so easy to find a “round face” among the bijin-ga. The following, by Yoshu Chikanobu is from 1897, well into the Meiji period (1868-1912), and shows its model holding her fan in a flamenco position, which is an emphatic marker of Westernization:

Perhaps part of the problem lies in how to reconcile the naturalistic look of a “round face” with the convention of the bijin-ga to depict its subjects as having long slender faces. There is a gesture made to “round” the face to some extent, about the chin and hairline; but one would have to describe the face more as “oval.” The bijin-ga subjects are sometimes referred to as conventionally having “rectangular” faces. At the same time, the curves in Chikanobu’s Shin Bijin may attempt to convey a degree of plumpness of the face perceived at three-quarter profile.

Still, Morris maintains that “Later artistic representations of beauties often showed petite women with round faces, straight eyes with flat eyelids, and small receding chins” (21). Furthermore, it seems to me that, in the case of a maiko, or apprentice geisha, the application of thick white makeup over the entire face, does tend to de-accentuate the protrusion of facial features, thus maximizing its perceived roundedness. Fully qualified geisha do not wear the opaque white makeup (once made from toxic lead, which was banned in 1934 and replaced with rice powder.)

Wagatsuma writes how, during the Edo period, aesthetic norms underwent a transformation: “Gradually, slim and fragile women with slender faces and up-turned eyes began to be preferred to the plump, pear shaped ideal that remained dominant until the middle of the eighteenth century” (15). However, there is a mention in a 1949 novel by Ibara Saikaku, of “A beautiful woman with a round face, skin with a faint pink color, eyes not too narrow, eyebrows thick, the bridge of her nose not too thin, her mouth small, teeth in excellent shape and shining white” (Koshoku Ichidai Onna [The Woman Who Spent Her Life at Love Making], Tokyo, 1949), p. 215.

In the following passage, the novelist Ishibashi Ningetsu describes a beautiful woman:

[I]f we see her from behind, she is slim and slender, with a long nape— her neck is thin and whiter than snow, standing tall and straight — that in itself makes us guess her beauty; if we see her from the front, she has an oval face, a complexion like a plum blossom blooming in the cold, mixing eight parts pure white with two parts pale red, and the way she keeps her tiny adorable lips sealed epitomizes the gracefulness of her whole body; but even when she laughs, those lips express the attractiveness of her whole body. You ask why? I’ll tell you why: it’s because within those blushing petals of her red lips, her teeth play hide and seek like gourd seeds; it’s because each of her appropriately plump cheeks comes endowed with its own whirlpool of Naruto.

Princess Tsuyuko (“Tsuyukohime,” 1889)

Indeed, she seems nearly good enough to eat — her skin tones recalling the distinctive spiralling red on white colors of the traditional rolled naruto fish cake!

First Miss Japan, 1908

Traditional influences apparently held sway through Jibun’s time in late Meiji, c. 1908, despite the influence the West had exerted over Japanese values and aesthetics. In 1908, the winner of the first official nationwide beauty contest, Miss Hiroko Suehiro is described as having a “round, pale face, a small mouth, and narrow eyes,” features that “some Japanese scholars cite as […] expressions of the values of submissiveness, gentleness, and modesty” (Miller, 2006, p. 21). We might notice the plumpness of Hiroko’s cheeks, and the relative roundness of her face, particularly as emphasized by the hairstyle. But her nose is quite long. The closer you look, the more relative such measures seem to become; after all, beauty truly is in the eye of the beholder.

Incidentally, sixteen-year-old Hiroko, the daughter of a city mayor in Fukuoka prefecture, had been a student at the female equivalent of Mushanokoji’s own aristocratic school, attending the elite Gakushuin Girl’s College, or Peeresses’ School in Tokyo. The Chicago Tribune and Jiji Shimpo, an influential Japanese newspaper, co-convened the contest, judging the 7,000 contestants on their submitted photographs. The prize was to be an 18-carat diamond ring worth 300 yen (about 1 million yen today).

Hiroko’s uncle submitted her photograph unbenownst to her. Thirteen judges included Kabuki actors, “Western-style” painters, and doctors. Unfortunately, the Gakushuin Women’s College took a dim view of her participation in the competition, previous beauty contests having been held only for geisha. The school considered expelling her, harkening to the words of the School President, Baron Nogi Maresuke, a war hero in the Russo-Japanese war (1904-5) and a general in the Japanese Imperial Army, as well as former Governor General of Taiwan. He said of Hiroko’s case:

In the educational policy of nurturing good wives and wise mothers, flaunting one’s appearance is an act that is unbecoming of a student, and has a bad influence on other students.

Cited in Kusanomido,com

The school offered Hiroko the option of withdrawing voluntarily, which she did. At any rate, a year and a half later, Hiroko married a twenty-four year old marquis and artillery lieutenant, Shizunosuke Nozu, whose father had fought with General Nogi in the Russo-Japanese war. It was rumoured that the general had mediated the marriage out of regret, but the fact is that the couple’s fathers were old friends, and the marriage had been arranged between the two families over some time.

As you progress with Mushanokoji’s The Innocent, you will be surprised at some of the parallels between the Hiroko Suehiro matter, and Jibun’s quest to marry his beloved Tsuru, and various other incidents. They are more likely a function of class hierarchies and social customs than any use by Mushanokoji of the case itself. However, there would seem to be little doubt that he would have been extremely aware of the controversy.

Further reading and reference:

Tsuru and Jibun: elements of Chapter Two

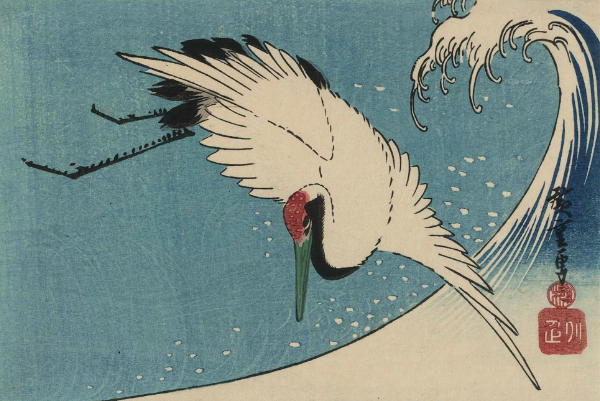

The wave pictured below recalls Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa, but this print is by another famous ukiyo-e artist. Here Hiroshige depicts a Japanese crane, the “bird of happiness,” symbol also of good luck, long life, and fidelity. Mushanokoji uses the Japanese word for crane—tsuru—as the name of his “ideal woman,” Tsuru, whom the “I” in the novella obsesses over.

It is a powerful and economical gesture by Mushanokoji. He invests the young woman’s name with symbolic overtones that encapsulate Jibun’s quest for happiness. Tsuru embodies Jibun’s ideal—or rather, he projects his ideal upon her. In the same action, he internalizes an image of Tsuru, such that she is contained in his psyche.

Although I refer to the narrator-protagonist as Jibun, this is simply the word for “myself” (reflexive pronoun) that occurs throughout the Japanese text. It is a convenient way to refer to him in the third person—a commonplace in English criticism on the I-novel (shishosetsu) (see, e.g., Fowler).

Mushanokoji’s use of symbolism contributes to the economy of the work as it unfolds before us. This brief Chapter Two is minimalist in the way it develops the outlines of Jibun’s psyche, through his reflecting upon his own peculiar thought processes. Less is more. Bear in mind the autobiographical, confessional nature of the I-novel. We can think of these reflections as sincere observations, not necessarily fictions.

We like to consider ourselves as rational beings, and to present ourself as such when we express our ideas and opinions to others. But underneath, how much of our inner dialogue is actually obsessive, repetitive, circular, and self-contradictory? We tend not to speak of such thoughts, but prefer to keep them private.

Jibun Reflects

Chapter Two continues to develop on the technique of self-examination and self-parody. His continous inner monologue is at once poignant, comic, tasteful, and insightful. A tender yet detached affection—the narrator sees his niece as an embodiment of innocence and familial love, yet she also serves as a quiet reminder of his own solitude, unfulfilled longing, and the uneasy distance between himself and the life he wishes to grasp.

I love Haru-chan too. She calls me “uncle-chan” and is very fond of me, but I cannot say that I am totally enamored. I live at home without anyone to love but myself.

I have not been able to taste love, nor do any work I enjoy. I do not know the joy of being a father and cannot help feeling as if I am going to die…

In the same mood, I walked aimlessly through the colorless town, a solitary feeling in my heart…

Further Notes and Reference

Saneatsu Mushanokoji, The Innocent (1911), trans. Michael Guest, Sydney: Furin Chime Press, 2024.

Bailey Irene Midori Hoy, “Joo wa Dare? Who is the Queen?: Queen Contests during the Wartime Incarceration of Japanese-Americans” (pdf), Winner of Madison Historical Review 2023, U of British Columbia.

***Fowler, Edward. The Rhetoric of Confession: Shishosetsu in Early Twentieth-Century Japanese Fiction. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988. Full text, html (UC Press E-Books Collection.)

Fraser, Karen M. in “Beauty Battle: Politics and Portraiture in Late Meiji Japan,” Visualising Beauty and Gender , ed. Ada Yuen Wong, 2012.

Kamei, Hideo. Transformations of Sensibility: The Phenomenology of Meiji Literature, Trans. Michael Bourdaghs, Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies 40, (Ann Arbor: U Michigan P, 2002).

Miller, Laura. Beauty Up: Exploring Contemporary Japanese Body Aesthetics (Berkeley: U of California P, 2006)

Patessio, Mara. Women and Public Life in Early Meiji Japan: The Development of the Feminist Movement. Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies 71 / (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan P, 2011).

Wagatsuma, Hiroshi [1967]. “The Social Perception of Skin Color in Japan“. Daedalus. 96 [2]

- I-novel (shishosetsu): Bear in mind that the shishosetsu was not formally theorized until at least ten years after the present novella appeared, when some attributions of “first I-novel” were attempted retrospectively.

- Haru-chan: The meaning of haru is spring (the season). The ‘diminutive suffix’ -chan attached to a person’s name expresses that the speaker finds them endearing.

- The first Tokyo Hyakubijin beauty contest, comprising 100 geisha contestants, was conducted in 1891.

English translation of Saneatsu Mushanokoji’s The Innocent (1911) by Michael Guest © 2024

Leave a comment